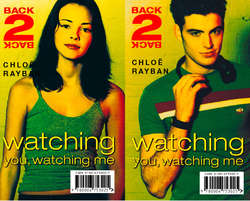

Читать книгу Watching You, Watching Me - Chloe Rayban - Страница 6

Chapter Two

ОглавлениеMornings in our house are always pretty unbelievable. But the first morning of any term gets the chaos award.

I left as much time as I reasonably could before I made my appearance downstairs. Mum had called six times. I climbed into my loathsome uniform. Grey skirt made as short as I dare by rolling round the waistband (a quick unroll adds that vital inch on uniform inspection days). Hideous white shirt you can see your bra through, yukk! I’d forgotten the gross feel of the nylony fabric — the kind of stuff that gives off electric shocks like forked lightning when you undress in the dark. Dangerous if you ask me. Tie — now I reckon it’s kinky making girls wear ties. And to complete the ensemble, scratchy nylon and acrylic mix grey cardie — ghastly!

I stomped downstairs. Gemma was sitting on the third step practising her recorder. The ‘tune’ she was attempting to master was ‘London’s Burning’. Every time she got to the two final notes — ‘Fire, Fire’ — she played two painfully wrong ones.

‘Shut up Gems — you’re giving everyone a headache!’

‘Miss Dawson said we had to have it perfect over the holidays.’

‘But you’ve had all summer!’

I climbed over her. Mum was dressed in her smart ‘I’ve got a meeting at work’ outfit and making sandwiches distractedly.

‘Oh, there you are. You couldn’t be an angel and find Jamie’s football gear for me, could you? It’s brand new, should be in the drawer but …’

‘He’s been wearing it as pyjamas,’ chimed in Gemma, appearing in the kitchen doorway.

‘I have not …’ said Jamie going red — and an argument broke out.

Mum tore open a tin of tuna and Yin and Yang started up a chorus at her feet.

‘Jamie, its your job to feed the cats this week. Why aren’t they fed?’

‘Mum!!!!! …’ Gemma was staring at the sandwiches practically in tears. You know I can’t stand mayonnaise. It makes me want to throw up. The very sight of it and I puke …’

‘Oh goodness yes … I forgot. OK … Tasha, you feed the cats and Jamie, you get your football gear.’

‘Dad came in. I couldn’t find them. Definitely not in the bedroom.’

‘What?’

‘The car keys.’

‘I don’t believe this! We’re going to be late,’ Mum fussed.

Gemma broke off in the middle of an ear-piercing wrong note. ‘Mu-um, we can’t be late on the first day. I’ll get a seat near the front …’

‘I’ll look for the keys,’ I offered — anything to avoid smelly cat food duty.

‘Hey Gems … its OK, your sandwich hasn’t got mayonnaise on now,’ said Jamie.

Mum leapt at Yang, who in the absence of breakfast, had seized his opportunity and was licking mayonnaise off Gemma’s bread.

‘If you smack him I shall ring the NSPCC,’ said Gemma.

‘Try the RSPCA, Gemma,’ suggested Dad. ‘Unless you continue playing that thing — then we might need both.’ And with that he scooped up his briefcase and escaped through the front door.

Mum headed upstairs.

Gemma poured milk on her cereal.

‘I wonder if he’s got any breakfast over there …’ she sighed to me.

‘Who?’ asked Jamie as he spooned cat food ever so slowly and carefully on to two saucers. Yin and Yang were practically going berserk at his feet.

I shoved the saucers under their noses.

‘Maybe we should make up a food parcel, like in a basket or something, and then he could let down a rope and haul it up to his room,’ continued Gemma in a dreamy tone.

‘Dad’s trying to get rid of him, not encourage him,’ I pointed out.

‘But what if he stays up there and starves to death? It’ll be our fault.’

‘He could have my tuna sandwiches and then I’d have to have school dinners,’ suggested Jamie generously. Mum didn’t approve of school dinners. She reckoned they served factory-farmed meat, and they had chips too which she insisted were really unhealthy. Jamie went positively dewy-eyed over the very thought of a school dinner.

‘Shall I make some toast for him?’

‘No, Gemma. Absolutely not.’

The last thing we needed was Gemma doing something typically cringe-worthy like sending over food parcels. Having her act of charity rejected, she returned crossly to the stairs and started up her recorder torture again.

Mum came down the stairs like a whirlwind, holding out Jamie’s football gear.

‘Gemma was right! They were in your bed.’

‘You’ve got a ladder in your tights, Mum. A really humungous one,’ remarked Gemma.

‘I haven’t! I have! The keys! Tasha we’re going to be so late!’

We were late. I found Mum’s keys in the fridge. I reckon Dad must have picked them up last night when he’d had the set-to with the ‘squatter’ and then shoved them in there when he’d got the beer. He’d been in a bit of a state.

So we all piled in the car, and just as Mum was trying to persuade it to start … this boy came out of number twenty-five. He shot through the gate that led round to the back garden, bold as brass as if he owned the place. He was really fit actually. I craned out of the back to get a better view.

‘Cor …’ said Gemma.

‘Gems, that is a really vile and vulgar expression,’ I said, signalling violently to her not to draw Mum’s attention to our new neighbour. Mum hadn’t seen him — she’d been too busy battling between the ignition and the choke. I prayed she wouldn’t realize where he’d come from. For all I knew, she’d be out of that car in a flash and doing a citizen’s arrest on him or something.

The car started at last and Mum coaxed it out into the street. He was ahead of us now, sashaying along on rollerblades, dead in the middle of the road, making it impossible for Mum to pass.

‘I don’t believe this!’ she muttered, really losing her cool. She hooted at him but he didn’t take a blind bit of notice. This guy had some cheek.

But Gemma was right — he was well ‘Cor!’ I mean, guys always look good on rollerblades — gives them extra height and all that. But apart from the nice build which I’d noticed as he came out, he had a really OK face too. He wasn’t unshaven as a matter of fact — he was pretty tanned as if he’d just come back from holiday and his hair was kind of rough and sun-bleached. I mean, he was about the best thing I’d ever seen down our street. Squatter or not — he was good news.

A milk float lurched round the corner and approached us. Now any chance of passing him was totally out of the question.

Mum put her hand down on the hooter again.

‘This young man is going to get himself killed if he’s not careful!’

She hooted again and waved wildly at the milkman. The milkman got her drift and went all officious, flagging him down as if he were a policeman. Our rollerblader suddenly came to an abrupt stop, and Mum nearly collided with him. The guy shot a glance over his shoulder and did an ace wobble and double-take, nearly landing on his backside. You should have seen his face!

‘Just what do you think you’re doing!’ Mum yelled at him. She always gets hysterical when she sees someone endangering themselves.

The guy recovered himself and took the two little foam Walkman speakers out of his ears. I could hear the jangle of the bass from inside the car. He must have had it on full blast. No wonder he hadn’t heard the car. The idiot! He stood there looking foolish for a moment. And then he caught sight of me in the back of the car. I was killing myself — silently, so as not to enrage Mum even more. He frowned, obviously realising what a total prat he’d made of himself.

‘Look — do you know the way to West Thames College?’ he asked.

‘I know the way to West London Cemetery — and that’s where you’re heading at this precise moment,’ said Mum.

‘Sorry but — you must’ve come from nowhere!’ he said.

Mum pointed at the head-set. ‘If you want to stay alive, I’d give that a rest if I were you.’

‘Yeah, well maybe …’

‘If I see you doing that again, I won’t be so lenient. I’ll run you over,’ she added.

‘Feel free … Mind how you go now,’ he said. And he waved her on with a flourish.

‘Hmmmph — he’s got a cheek,’ said Mum, but she kind of smiled to herself all the same. Then she thrust the gear lever into second gear and concentrated on getting us through the traffic to school.

OK — school. That first day back is never as bad as you think it’s going to be. You arrive there all ready to muster your reluctant brain-cells and force them back to work, then most of the day turns out to be timetable-planning and book lists and general reorganisation. All of this was carried out by harrassed teachers who were fighting a losing battle against our real purpose of the day — to find out what everyone else did on holiday and go one better.

Melanie deserved the all-time poseur prize because she’d been to the South of France and stayed on her uncle’s ‘yacht’ (i.e. power cruiser, but nobody was splitting hairs). Loads of people had been to Spain and were sporting tans to prove it. Jayce, the rebel of the class, claimed to have been on a caravan holiday with her boyfriend and went into a huddle with some of her mates over the steamier details. Rosie had spent two weeks in Tenerife with her Mum — she’d met this boy and had brought in tons of photos.

I just kept my head down. No-one needed to know about our two-week family walking tour along Hadrian’s Wall, did they? I’d enjoyed it, actually, in a masochistic sort of way. The weather had been fantastic and we’d taken field glasses and seen curlews and sparrow hawks and one day we’d even sighted a falcon’s nest. But I knew from bitter past experience that the very mention of bird-watching would bring the united weight of class scorn down on me.

I’d done an essay, a year or so back, about what I’d done on holiday, and got an A for it. I had to read it out to the whole class with Mrs Manners looking on and smiling indulgently. Dad had taken us to a place called Holy Island. It’s not really an island — its at the end of this causeway, but it’s cut off at high tide. It’s got a castle and an abbey but absolutely nothing else except marsh and sea and birds. I’d felt myself getting hotter and hotter as I read out all this stuff about the abbey and the monks and the curious sense of history in the place. I could hear people fidgeting and giggling beneath the sound of my voice.

That’s when I got friendly with Rosie. She’d come and found me in the cloakroom where I’d gone to get some peace. There’s a place between the coat racks where nobody can see you if you sit really still.

‘It’s OK for you,’ I said, blowing my nose on the tissue she’d given me. You went to Majorca. You’ve got a tan and everything.’

‘Yes, and Mum went out every night and I had to stay in this stuffy hotel bedroom and watch crappy films on the TV. The hotel was full of grossly overweight middle-aged couples getting sunburn round the pool — the women looked like red jelly babies and the men looked like Michelin men and they were all trying to get off with each other. It was disgusting.’

‘You didn’t put that in your essay.’

‘Course I didn’t, stupid.’

Rosie was brilliant like that. She didn’t tell lies exactly, she just knew how to present the truth in the right light for class consumption. If she went to Calais with her Mum on a day trip, she’d let drop that they’d popped over to France for lunch. If a boy asked her out she wouldn’t say he was fit exactly, she’d just find the right way to describe him. I’d got to know her shorthand and how to translate. Tall for his age (i.e. overgrown and weedy). Fascinating to talk to (i.e. gross to look at). Really fit and into sport (i.e. totally obsessed by football).

Anyway, unlikely as it seemed, Rosie and I had teamed up. I had an ally, a conspirator, a protector. However gross the girls in class might be to me, I always had Rosie to have a laugh with.

She was beckoning wildly to me now as a matter of fact.

‘How come you were so late in?’

‘Mum nearly ran someone over. This really gorgeous guy on rollerblades.’

‘She should’ve driven faster — you might’ve got acquainted.’

‘That shouldn’t be a problem. He’s moved into our street.’

‘You’re joking — a fit guy in Frensham Avenue?’

‘Stranger things have happened. Except we think he’s a squatter.’

‘In good old respectable Fren-charm.’ (She was putting on a posh accent). ‘All the local budgies will be falling off their perches in shock.’

‘Yeah well, we’re not sure yet.’

‘I better come’n check him out — like tonight.’

‘OK, you do that.’

I had double Biology at that point and Rosie went off to General Science so I didn’t see her again until after school.