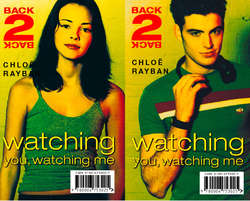

Читать книгу Watching You, Watching Me - Chloe Rayban - Страница 9

Chapter Five

ОглавлениеIt was some days after this excruciating first encounter that he was sighted again. But not by me this time. It was by Mum.

I was doing my French homework curled up on the sofa. I usually did this downstairs, hoping to glean a little help from Mum’s shaky command of French. She was pretty good on anything to do with food or travel.

I looked up and found her poised with the Hoover mid-way through cleaning the sitting room carpet. She was staring out of the window.

‘What is it?’

She switched the vacuum off.

‘Just take a look at that.’

‘What now?’ I was sorting a particularly difficult bit of past tense into imperfect and passé composé and didn’t want to lose the thread.

Jamie joined her. ‘Huh,’ he said with six-year-old disapproval. ‘He’s drinking out of the bottle.’

‘But it’s what he’s drinking …’ said Mum.

I could resist no longer. I joined Mum and Jamie and stared out as well.

Sitting on the wall outside number twenty-five, there was this boy with his hair shaved round the sides and cut in a sort of slab on top. He was taking swigs out of a bottle — a Smirnoff vodka bottle.

‘What did I tell you?’ said Mum. ‘Let squatters into the street and there’ll be nothing but trouble. I should call the police.’

‘No!’ I said. You can’t do that. He’s probably nothing to do with the house. I expect he’ll move on in a moment.’

This statement was immediately contradicted by the window two storeys above opening. A figure leaned out. It was him.

‘Come on up. I’ve found something better up here.’

I left the window in a hurry and went and sat on the sofa well out of sight.

Mum glared at me. ‘See?’

‘No, I don’t see,’ I said. You’re jumping to conclusions.’

Mum continued peering out of the upper window. ‘Look upstairs. It’s that boy from the other morning. The one I nearly ran down rollerblading. The one who had such a cheek.’

‘Oh … is it?’ I asked, trying not to sound in the least bit interested.

‘He’s our squatter,’ said Gemma, giving me a nudge. ‘Come away, It’s not fair on Tasha to stare at him like that.’

‘What’s going on?’ demanded Mum.

‘Tasha really fancies him,’ said Jamie in a matter-of-fact voice.

Gemma nudged Jamie hard.

‘I do not!’ I said hotly.

‘That would be just so typical!’ said Mum. ‘A girl with no problems whatsoever. Doing well at school. And then someone like that moves into her street and …!’ She paused, peering out again. ‘Oh that’s too much.’

‘So what’s going on now?’ I asked.

‘He’s smoking a big fat cigarette,’ said Jamie.

‘Stay well away from them. That’s all I’m going to say,’ said Mum. She started vacuuming again in a haphazard way with one eye on the window.

Mum thinks she knows it all. She’s got this part-time job as an educational psychologist. She’s used to seeing kids that have gone off the rails. She spends her whole time sorting out disputes, counselling people who’ve been expelled and helping to fix up places in special schools. I reckon it makes her over-react sometimes.

‘I’m going upstairs where I can get some peace to finish my French,’ I said.

I settled down lying on my stomach on my bed facing the window. My room was in shadow so I knew no-one could see in. The guy with the flat-top haircut was leaning out of the attic window opposite, smoking now. And it didn’t look like an ordinary cigarette. He still had the vodka bottle in his hand. He looked down and waved it in the direction of our living room. He must have caught sight of Mum watching him.

The two boys appeared to be fooling around the ways boys do when they think they have an audience. I could have killed Mum. She must be staring out through the window. And they were certainly making the most of it.

The boy waved the bottle again. It was nearly empty now. How on earth could squatters afford to drink vodka like that? That’s if it was vodka, of course. I was starting to have my doubts. The way the boys were fooling around didn’t look totally convincing to me. The chap with the flat-top haircut was really camping it up. He stood at the window and made his eyes go completely crossed and then fell over flat, backwards. I was killing myself.

Mum must’ve been going ballistic down below.

The falling-over act seemed to conclude the show. They’d disappeared from sight. I wondered what it was like being a squatter. What did they live on? Social Security? Was the house filthy and vermin-infested like Mum said? If I lived in a squat I’d make the place exactly how I wanted it. I’d paint the walls black or silver maybe. Perhaps I’d paint murals all over them — and I’d find things in skips and do them up. It must be absolutely fantastic being able to do exactly what you want with no parents around. Being able to stay in bed as long as you want, for instance — eat what and when you like — play music as loud as you like — go out wherever and however late you like.

My parents are really repressive. I reckon it has a lot to do with the fact I’m the eldest. I haven’t had someone up ahead of me to kind of break them in — establish the ground rules. They’re always easier on Gemma — she can do things I was never allowed to do at the same age. By the time Jamie’s my age they’ll probably have given up rules entirely. It’s so unfair!

The boys didn’t reappear. I rolled over on my back and stared at the ceiling. Out of all the girls in my class I reckon my parents are the strictest. Maybe some of it’s boasting, but from what I’ve heard, other girls my age are allowed to go out loads more than me. They dress up and get into pubs and clubs. My parents would have a fit if I did any of those things. They still think I’m a child.

I sat up and stared at my reflection in the bedroom mirror. I even look young for my age. I didn’t stand a chance with a guy like the one over the road. He’d hardly want to be seen around with some kid.

You know what Mum says? It’s the most depressing and infuriating thing anyone can say: ‘Your turn will come, Natasha.’ Well, I simply don’t believe it. By the time it’s my turn, it’ll be too late.

I lay there for quite a while trying to summon up the energy to finish my French homework. I strained my ears for sounds from the house opposite but I guess the boys must have gone out or something.

It was a warm evening and my window was open. I could hear the anxious cheeping and scrabbling of the house-martins. They made a rough mud nest under the eaves of our house every year. This one was just above my bedroom window. Gemma was doing a nature project on them for school and was always barging into my room to check on them. It had been a bit of a pain to start with, but then I couldn’t help getting involved. This summer the parents had brought up three separate broods of fledglings. So there had been constant comings and goings as the parents tried to keep up with their demand for food. I could see a couple of martins darting back and forth across the street catching insects right now. I loved the way they always looked so neatly dressed in black and white — like an anxious pair of waiters in a smart restaurant, with a load of diners grumbling about the time they took bringing the food. And it wasn’t just the adults who did the work. Later in the year — like right now — the earlier, older fledglings would join in and help feed the younger ones. You’d think they’d prefer to be off on their own somewhere, wouldn’t you? Flying down to Spain perhaps, sorting out where they were going to spend the winter? Instead, they were stuck at home doing chores for Mum and Dad. I’d started to identify with some of those martins over the course of that project.

Gemma had wandered into my room.

‘Hi,’ she said, sitting down on my bed beside me.

‘What’s up? Nothing on TV?’

‘Just wondered what was going on over there.’ She indicated the window over the road.

‘Absolutely nothing.’

‘Oh. Sorry about letting on to Mum.’

‘I’ll survive.’

‘But you do fancy him, don’t you?’

‘He’s all right.’

She leaned towards me and asked in an undertone: ‘Do your knees go to Jell-o whenever you see him?’

‘Go to what?’

‘Jell-o.’ She paused. ‘What is Jell-o?’

‘Jell-o is American for jelly. And no, they don’t as a matter of fact. Honestly, Gem. I don’t know what you see in those books.’