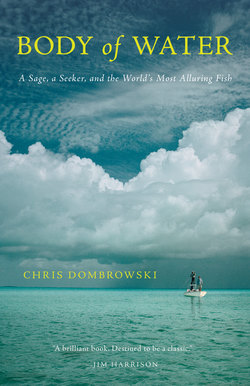

Читать книгу Body of Water - Chris Dombrowski - Страница 13

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеAlbula vulpes

A fish together with other fish invariably knows what is on each other’s mind. Unlike humans they are not ignorant of each other’s intentions.

—DOGEN

I sat often at my computer looking at the picture turned screen saver that Miller had sent of me holding my first bonefish, my eyes beaming over soon-to-be-sunburned cheeks. Though I’d caught thousands of fish in my lifetime, I’d doubted I’d ever been so elated about one that so closely resembled a minnow. Lacking the dangerous stiletto-shaped allure of a barracuda, say, or the simple polished-penny sheen of a redfish, or the azure panache of a dorado’s dorsal fin, the bonefish possesses the beauty, rather, of certain mirrors or windows.

Despite its homely appearance, its mouth shaped, in one writer’s words, “like a rechargeable vacuum cleaner,” and its relatively modest average size, the bonefish has attained sport fish–royalty status due largely to its fickle manner and unsurpassed acceleration. With sturdy caudal fins fanning winglike from its flanks, the fish is built for departure. Tail tip to sloped nose, its belly is nearly level, recalling, in profile, Pterrichthyodes, “the first fish,” which swam early seas 350 million years ago.

Weighing only a third of a pound in salt water, a fusiform bonefish of six pounds shuns its element. Fleeing boat or boat’s shadow, a lemon shark or a conspiring pair of barracuda, the bonefish can reach speeds of up to twenty-five miles per hour swimming in water that is 760 times denser than air—I would have to sprint at an equivalent speed through waist-deep Jell-O to experience similar resistance.

When not fleeing danger, the bonefish avoids it by means of intricate disguise, its shadow nearly always more visible than its body. Over white sand, the fish appears the color of watered-down skim milk; over turtle grass, on a knee-deep subaqueous prairie, the fish jewels up, turning the color of some yet-to-be-discovered gem; traversing coral heads or mangrove roots, the fish goes sepia, the density of the pigment cells beneath its fingernail-shaped scales varying from moment to moment to match its environment.

Because of its considerable speed, the bonefish is rarely pursued in blue water by its predators. On the flats, however, the more herdable bone becomes a mark for teams of blacktip sharks, bonnetheads, and lemons. Ospreys traffic the air above shallow saltwater acreages, but rarely seek out adult bonefish when easier game abounds. The archipelago’s first people netted bonefish, making the quarry keener to shore-walking humans’ thudding vibrations—vibrations sensed in the fish’s lateral line, a thin, tail-to-cheek organ that detects movements in the water. Centuries later the disturbing plop of a bell sinker followed shortly by the slightly quieter but equally alarming smack of a shrimp-threaded bait hook were added to this list of affronting sounds, the many suggestions of imminent death.

If desperate for safety, the fish seeks out like company: more eyes to watch for danger, more sensory organs alert. Despite its tendency to school, Linnaeus named the bonefish after a solitary mammal, and a conspicuous one at that: the white fox. The eighteenth-century naturalist, of course, had never seen an actual bonefish, and must have focused on sketches of the fish’s canine nose. In Central America the bonefish is called ratón for the way it scurries briskly from the minutest piscatory failings. Among anglers, gray ghost is the preferred and perhaps most telling moniker; it is rarely visible to the average human eye, and a sighted fish is usually a fish in flight.

OUT IN THE BLUE WATER, FAR OFFSHORE AND FAR BENEATH the swelling surface of the sea, a large school of bonefish has gathered in the September dusk to spawn. A thousand or more staging fish, uniform in length as bars of silver. Through a paling shaft of light, the shimmering tornado made of scales and fins and eyes moves hypnotically, slowly circling an invisible axis. As the full moon lifts, the fish one by one abandon their rotation, rising toward the roof of their world to breach and gulp air, which helps males and females expel, respectively, sperm and roe that drop together from the cusp of an underwater terrace—hundreds of millions of eggs falling through spreading clouds of milt.

For several weeks the fertilized eggs rest on the ocean floor’s good darkness, in one of the few places we know blessedly little about. Then from the eggs heads and ink-splotch eyes protrude as the fish begin their forty-day larval stage, expanding in this form until they are two inches long and metamorphosis begins. Before they continue to grow, they must shrink—maturing implausibly in reverse, contracting through the leptocephalid stage over a ten-day period. Nourished on plankton, they soon look quite like miniature, one-inch bonefish, creatures protected by the same number of scales from birth to death.

BONEFISH SURVIVING THREE DOZEN MOONS WITHIN THE relative protection of mangrove swamps will mature sexually and grow into one of the world’s most coveted game fish—such as the flat-foraging specimen I cast toward now, which, curse instinct, disengages from its school and mistakes this traveling angler’s artificial fly for a live, fleeing shrimp. When the false prey is attacked, a steel hook dressed with feathers bites into the fish’s bony palate.

Quickened along with the fish, I brace against its first blistering run, wet line peeling off the reel and spraying onto my face and polarized lenses. Very soon the fish is farther out than I can see, struggling against the rod’s full bend to reach the edge of the flat where the seafloor falls abruptly into the fathom-deep green. Like exaggeratedly slow seconds ticking off on a watch, line clicks off the reel one gear rotation at a time. As the distance increases, so does the tension on the line, on the knot joining monofilament leader to fly. For a hundred yards—from fish to fist gripping rod cork, from shoulder to heel seated in the sand—there is connection, like a long tendon, stressed to its tearing point.

This tug, as anglers visiting the islands say, “is the drug,” a quick hit of adrenaline initiated by a hooked and fleeing bonefish, and one the Bahamian tourism industry counts as an invaluable commodity, having recently gauged the industry surrounding the scarcely edible fish at roughly $150 million annually.

I lean the rod low and the fish finally cedes, and, reel turn by reel turn, comes to hand. I hold it upside down with shaking wrists to disorient it, and dislodge the artificial fly from its jaw. Hook free, the fish is righted, vulpine snout to the sand, and rocked briefly like a small child in a bath, one hand behind the head and one hand at the tail, to circulate salt water through its gills. Revived in its element, it tightens, kicks, and heads for refuge, meeting a curtain of sand near the edge of the flat stirred up by two feeding spotted rays, and parting the murk opposite the tidal bore.

A rising orange sun laces its hazy light across the basin and my shadow clocks westward, a visible indication of a presence already sensed by the fish’s schoolmates. Previously unnoticed, a short backhand cast away, the substantial congregation of fish arcs across the wales of sand, fleeing its birthright flat for a deeper corridor of water, reminding the angler that the ocean is an aggregate of all perceptions, not just his human ones.