Читать книгу Body of Water - Chris Dombrowski - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

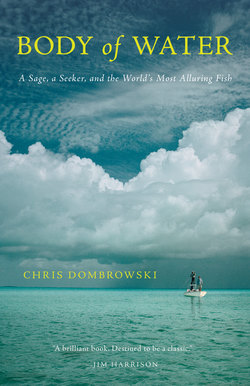

ОглавлениеPrologue

The man steps barefoot through shallow water, moving as if he carried a candle threatening to expire. He lifts his left foot from the ankle-deep slack tide and holds it poised in the early-morning air until the last drops from his pant cuff return to the salt. Then he advances, setting his foot down toes first, dark brown on the pale Caribbean sand.

Now he stands so still a passing cormorant might light and perch on his shoulder, mistaking man for mangrove.

Now he proceeds.

So that a single bonefish feeding along the tidal flat’s periphery won’t startle, he walks this way; so his wake won’t alert the nearby assemblage of mojarras, the myriad minnow eyes trained already on his shadow. He holds the borrowed fly rod behind his back, a strange nine-foot tail, so that its lacquered finish won’t redirect sunlight toward the fish. Again he steps, closing the distance between his body and his quarry’s hovering form, its bottom-cast penumbra.

Sensing danger, the fish maintains shrewd space and near invisibility. Since it arrived on the flat, the five dark vertical stripes have disappeared from its flanks, and before that its scales maintained the hue of the narrow blue defile it negotiated on its way to these shallow feeding grounds. Now its sides are star white, chalky, its location perpetually vague and mirroring whatever surrounds it until it tilts, nose down, to root a bellicose crab from a burrow. Then its sloped back and dorsal fin cut through the surface, light shellacked, announcing its location to the airy world.

Its tail shimmers, a loose-fitting bracelet affixed to the wrist of a beautiful woman seated at a bar, the likes of whom the man has seen only in movies, or through the dining room window of the fishing club where he works. Before the foraging fish, a puff of inhaled sand the fish’s gills expel, clouding its vision. The man gains a yard while the water clears and the fish finishes pulverizing the crab with the crunchers in the back of its throat. Then he stills again and waits until the hovering fish inverts its nose, now pink from the rooting, toward another meal.

Low on the horizon, a single crown-shaped cloud lifts toward the rising sun. The man’s sighting light is limited; when the cumulus obscures the sun, the water’s surface will turn opaque, gray as a blind eye. The tide is due to turn and the south wind, low now but sure to advance with the day, will harry the incoming water onto the flat, pushing the lone fish into an apse of mangroves, a maze of many-fingered roots. Small, eager snappers will emerge there, busying the water, quick to jump on his offering before his fish has a chance. Schools of loose-scaled green fry frequent the cove as well, behind which the big predatory Cubera are never far—once he saw a fifteen-pounder annihilate a whole school: when it finally settled, the water looked strewn with tiny emeralds.

“Get yourself another crab,” he whispers, and commences tugging twenty reams of yellow fly line from the Medalist reel seated at the base of the rod. The reel’s gears click slightly as he pulls—he looks to see if this has altered the fish’s posture, but the fish seems unbothered. Soon the loose fly line lies in coils in the water around his ankles, and he holds the fly in his hand, letting ten feet of clear monofilament leader dangle like a luffing sail at his side.

Fortune: the fish has tipped down again to feed, this time with its tail facing toward him. He takes two careful steps and begins his back-cast, extending his right forearm out and upward from his elbow, flexing the fiberglass rod deeply so that, springing, it propels the slack line behind him. The line straightens, bristling with water like a long, lit wick.

Here the fully extended back-cast, waiting for the forward cast to propel it to its destination, breathes: a pause, an emptiness at the root of which all good lies.

The forward cast: a tug against the tension the back-cast established, a punch through the humid air that cannons the poised line forward parallel to the water. Because the edgy fish navigates such a shallow element, the man knows his fly must land like a feather—it must alight, not land. He finishes his cast high, right hand reaching above his head so that the forward-traveling line extends upward and outward from his body, and the fly at the end of the tippet at the end of the leader at the end of the line lists toward the water before landing, a detectable but not irksome disturbance.

The fish turns, scurries a short yard to the south, and puts eyes on it: a stainless steel hook wrapped with brown thread, two upwardly pointing tips of hackle borrowed from a rooster’s cape, and a set of brass bead-chain eyes wrapped liberally with pink chenille yarn. A shrimp in flight, a crab wielding its pincers, a benthic worm protruding from a hole in the seafloor: the man couldn’t care less what forage the fish mistakes the fly for, so long as it’s taken. Now his rod hand and line hand come together as if in the briefest of prayers, and he gives the loop of line below the reel a tug, so that the lure dashes across the sand in irresistible faux flight.

Dithering, the fish stares squarely at the fly, but before the man can play puppeteer again, it pivots its body to inhale. The man feels the pulse-like thump that tells him fish jaw has ceded to hook point, and, tugging again, feels the sweet stretch of the monofilament leader travel through rod blank and cork handle to hand. The fish torques, readies its body to burst for the horizon; the man raises his now equally torqued fly rod, and the line connecting two creatures—across which the sun’s ancient and instant light stretches—comes taut.