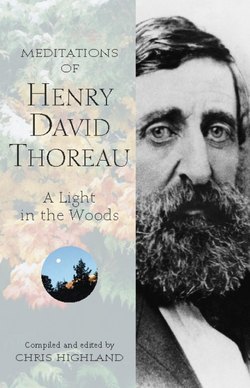

Читать книгу Meditations of Henry David Thoreau - Chris Highland - Страница 5

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеIntroduction

“I believed that the woods were not tenantless, but chokefull of honest spirits as good as myself any day—not an empty chamber, in which chemistry was left to work alone, but an inhabited house—and for a few moments I enjoyed fellowship with them.” 1

—Henry David Thoreau

Maine Woods

When he adventured into the Maine Woods in 1846, the 29-year old honest spirit Henry David Thoreau had already been a tenant at Walden Pond in Massachusetts for a year (since July 4th, 1845). The deeper, “inhabited house” of the north woods enticed him to deepen the spiritually-guided botany that characterized his life. He sought the extraordinary in the common and he found it. There, as everywhere, he felt something present that the civil world, the village, couldn’t see, hear, or feel. He opened himself to taste what he would later call “the flavor of life.” A flavor one can only savor when “obeying the suggestions of a higher light within.” 2

One evening, after noticing an eerie glow in a dead log deep in those Maine backwoods, he investigated the natural phosphorescence and remarked that he had given scant thought “that there was such a light shining in the darkness of the wilderness for me.” He concluded that he had more to learn from the forest and its inhabitants—including the Native peoples who held their own light—than from any wisdom he carried along. It was a liminal moment for him—a threshold illuminated with wild, blood-swirling mystery.

Thoreau (rhymes with furrow) is one of those eminently quotable persons in American history who seemed to have plowed himself into the landscape of the New World. His eye was trained on the ever-renewing fecundity of worlds at his feet. Collecting his thoughts is, for us, a kind of inner-farming—tilling, hoeing, harvesting the heartland of his, and our, richly American home. As his former housemate and devoted colleague Ralph Waldo Emerson eulogized, “His eye was open to beauty, and his ear to music. He found these, not in rare conditions, but wheresoever he went.” 3 His legacy is a lasting map into Beauty.

Thoreau walked into the natural world and felt the world walk into him. Emerson recalled Thoreau saying he could find his path in the woods at night “better by [my] feet than [my] eyes.” 4 Fiercely independent yet welcoming enlightened human society, he constantly went to the forest for the inspiring companionship of “kindred” Nature. There he found, again in Emerson’s words, that his closeness with Nature “inspired his friends with curiosity to see the world through his eyes, and to hear his adventures.” 5

His insight resounded into the twentieth century, spiriting the activism of shakers like Mahatma Gandhi and Martin Luther King, Jr. and activating the spirit of movers like Sigurd Olson and Dorothee Soelle. What Thoreau saw with his eyes and felt with his feet continue to kindle a lamp for the walk of new generations.

In Henry David Thoreau our modern eye can see a new light. His lucent wisdom warms a rich and sprouting garden of earthy spirituality composted with a keen sense of scientific and philosophical investigation. Thoreau models a specially balanced inquisitive mind that integrates the most profound discoveries of the heart and soul. He embodied the traits of both preservationist and religion professor. He personalized an exciting and fresh paradigm for a symbiosis of related disciplines including philosophy and ecology—a relationship that remains today both rare and sorely needed. Thoreau’s intimacy with the world at his feet touched his hands, his head, his whole being and sunk in. This is best illustrated by his delight in digging into the earth, literally and figuratively, turning over rich soil for reflection and introspection. Because he knew he was made of that earth, he could open himself to the mystery just under the surface, revealed by Nature’s playful and parental care. “Perhaps Nature would condescend to make use of us even without our knowledge, as when we help to scatter her seeds in our walks, and carry burs [sic] and cockles on our clothes from field to field.” 6 The baggy-pants botanist may not have known it, but his clothes bore wondrous seeds for future planting and reaping.

A Light in the Woods is arranged to suggest pilgrimage. We join Thoreau along with poets, writers, spiritual guides, shamans and saints, to saunter as sojourners deeper into Nature’s miracles. When I first walked alongside Henry in college I knew that he would be with me for years ahead. Every essay or poem inspired me to write and be present in my daily life and yet to remember that words alone cannot express the depths of the heart. For that class at the university I memorized a simple line that stays with me still: “My life has been the poem I would have writ. But I could not both live and utter it.” 7 I believe this is what the great teachers meant when they urged an awareness of the Word beneath the words, the Way beyond the path, the Torah or Gospel hidden near at hand, behind the awe-filled silences that mark moments of being human.

This book is a companion for you to carry with open curiosity into the beauties and wonders of the new worlds around you. Thoreau, like Emerson, like Muir in other woods, whittled a down-to-earth philosophical spirituality in the woods of New England. No matter where we live or journey, his roots are ours. And as we find our own Waldens, we can ask the same question Henry asked on the shore of the pond, “Why has humanity rooted itself thus firmly in the earth, but that it may rise in the same proportion into the heavens above?” 8 We are rising, and as we lift our spirit, we can bow in gratitude for the Concord pilgrim’s wisdom. “Heaven is under our feet, as well as over our heads.” 9 Looking down or looking up, his words seed and water our inner land, and we rise fresh and renewed.

Thoreau’s wisdom can be tasted like tea by a mountain lake and inspire days and nights as you saunter through sunlight or moonglow. Let him be a trusted companion, in all places where we hear the one calling out in the wilderness—the young, noble soul who, like the prophets of ancient times, found a strange and special spiritual light in the wildest places of his native land.

—Chris Highland,

Fall 2002

“The soul is a lamp whose light is steady, for it burns in a shelter where no winds come.”

~Bhagavad Gita