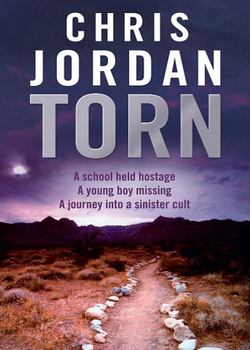

Читать книгу Torn - Chris Jordan, Chris Jordan - Страница 5

Humble, New York 1. A Simple, Ordinary Lif

ОглавлениеThe day before my son’s school exploded, he asked me if heaven has a zip code. We’re having breakfast, me the usual fruit yogurt, Noah his mandatory Cocoa Puffs, cup of ‘puffs’ to one-half cup milk, precisely. He licks his spoon, gives me that wide-eyed mommy-will-know look, and asks the big question.

“Not a real zip code,” he adds, “a pretend zip code, like for Santa. Like for writing a letter to Dad. Just to say hello, let him know we’re okay and everything.”

It’s a strange and wonderful thing, the mind of a ten-year-old child. Last night, as we read our book before bed—the very exciting Stormrider—Noah had asked, out of nowhere, “How we doing, Mom?”

We’d both known exactly what he meant by that—the slow, painful rebuilding of our world—and without missing a beat I’d responded, “We’re doing okay,” and he’d filed it away in his amazing brain and twelve hours later, out pops the idea of writing a letter to his dead father.

“You write it,” I suggest, “I’ll find out about the zip code.”

“Deal,” he says, and grins to himself, mission accomplished.

Then he calmly and methodically finishes his cereal.

My husband, Jed, used to say that Humble, New York, was well named, but only because ‘Hicksville’ was already taken. Humble being a small, one-of-everything town thirty miles outside of Rochester. One convenience store, one barber/beauty shop, one police station, one firehouse, one elementary school. At last count there were more farm animals—mostly dairy cows, cattle, and sheep—than people.

We moved here shortly before Noah was born and my first impression wasn’t exactly positive. I’m a New Jersey girl, a mall rat at heart, and the idea of living upstate in sight of a cornfield wasn’t exactly my dream come true. Postcards are meant to be mailed, not lived in. But Jed was convinced a small town would be safer than Rochester, where he’d just been hired, and which has the usual problems with poverty, drugs, and empty factories, so when he found the ‘perfect old farmhouse’ on the Internet there was no way I could say no.

Not that I ever said no to Jed. What he wanted, I wanted. We agreed that we had to get out of the city, had to make a new life for ourselves, as far away from his crazy family as possible. It was all good, and for a while—nine wonderful years—we lived the American dream, or as near as real people can live it. Not that everything was perfect. Sometimes Jed brought home his job tensions—he was an electrical engineer with a struggling company, lots of pressure there. Sometimes I let my resentment—how did his family situation get to run my life?—overpower my own good sense.

Sure, we squabbled now and then, all couples do, but we never went to bed angry. That was our rule. Arguments had to be settled before we hit the sheets. I’d grown up in a family that fought—my parents divorced when I was in high school—and Jed’s parents had been, to say the least, dysfunctional as human beings, and therefore more than anything we’d both longed for normality. A normal family in a small town, living a simple, ordinary life. The fact that Jed’s family was far from normal no longer mattered, because we were making our own family, our own life, far from them.

Along the way this suburban Jersey girl got pretty good at stripping old plaster, hanging new Sheetrock, painting and wallpapering, the whole nine yards—whatever that means. My old posse would just die if they knew prissy little Haley Corbin had learned how to solder leaky pipes, unclog blocked drains, refinish old kitchen cabinets. With Jed working so hard, and being dispatched as a troubleshooter to distant locations, much of the ‘perfect old farmhouse’ renovation was left to me. I had no choice but to take off my fabulous custom-lacquered fingernail extensions and get to work. This Old House and HGTV became my gurus. I attended every workshop offered at the nearest Home Depot.

I took notes. I paid attention. I learned a thing or two.

My personal triumph, after studying a chapter on home wiring repairs and puzzling over a diagram, was wiring up a three-way switch for a new light in the foyer. Jed was truly amazed by that little adventure. I mean his jaw dropped. Claimed my body had been taken over by alien electricians. I offered to flip his switch, and did, right there on the stairs with Noah fast asleep in his crib.

Life was good. No, life was great. We’d done it. We’d managed to escape from a really bad scene and get a new start. Then it ended, as sudden as a midnight phone call, and the kind of hole it left cannot be plastered over, not ever. The best you can do is push your way through the days, concentrate on being the best mom possible, even if you know in your bones it can never really make up for what’s missing.

Lately Noah seems to be faring better, which is good. He’s not acting out in class quite so much. He’s testing me less, a great relief. That’s the thing about kids. When the impossible bad thing happens, they accept it. Eventually they adapt, and, as the saying goes, ‘get on with their lives.’ One of those clichés that happens to be true. But really, what choice do we have?

“Mom?” says Noah, holding up his wristwatch. A gift from his dad he has never, to my knowledge, taken off.

“Ready?”

“Like five minutes ago. You were noodling, Mom.”

Noah doesn’t approve of me ‘noodling’because he thinks it makes me sad. He may have a point. I feel better when I’m busy, focused in the moment. Not wallowing in daydreams.

Moments later we’re out the door, into the car.

Noah never takes the bus to school, not because he wouldn’t like to—he has made his preference known—but because of the seat belt thing. No seat belts in buses, which drives me nuts. We’re legally required to strap them into car seats until they shave, make sure they wear helmets while riding bikes and boards, but school buses get a pass? What’s that all about?

Jed always thought I overreacted on the subject and maybe he was right, but I can’t help picturing those big yellow buses upside down in a ditch, or in a collision, small bodies hurtling through the air like human cannonballs. So I drive my boy to Humble Elementary School—distance, three point four miles—and see him inside the door with my own eyes. And when school gets out I’ll be right here waiting to pick him up and see that he gets home safely.

A mother can’t be too careful.