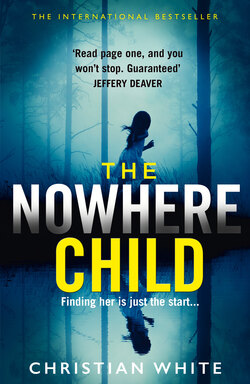

Читать книгу The Nowhere Child - Christian White - Страница 7

MELBOURNE, AUSTRALIA Now

Оглавление‘Mind if I join you?’ the stranger asked. He was somewhere in his forties, with shy good looks and an American accent. He wore a slick wet parka and bright yellow sneakers. The shoes must have been new because they squeaked when he moved his feet. He sat down at my table before waiting for an answer and said, ‘You’re Kimberly Leamy, right?’

I was between classes at Northampton Community TAFE, where I taught photography three nights a week. The cafeteria was usually bustling with students, but tonight it had taken on an eerie, post-apocalyptic emptiness. It had been raining nearly six days straight but the double-glazed glass kept the noise out.

‘Just Kim,’ I said, feeling mildly frustrated. I didn’t have long left on my break and had been enjoying my solitude. Earlier that week I’d found a worn old copy of Stephen King’s Pet Sematary propping up the leg of a table in the staffroom, and since then I’d been busily consuming it. I’ve always been a big reader, and horror is a particular favourite of mine. My younger sister, Amy, would often watch in frustration as I finished three books in the same time it took her to read one. The key to fast reading is to have a boring life, I once told her. Amy had a fiancé and a three-year-old daughter; I had Stephen King.

‘My name is James Finn,’ the man said. He placed a manila folder on the table between us and closed his eyes for a moment, like an Olympic diver mentally preparing to leap.

‘Are you a teacher or a student?’ I asked.

‘Neither, actually.’

He opened the folder, removed an eight-by-ten-inch photo and slid it across the table. There was something mechanical about the way he moved. Every gesture was measured and confident.

The eight-by-ten showed a young girl sitting on a lush green lawn, with deep blue eyes and a mop of shaggy dark hair. She was smiling but it was perfunctory, like she was sick of having her picture taken.

‘Does she look familiar to you?’ he asked.

‘No, I don’t think so. Should she?’

‘Would you mind looking again?’

He leaned back in his chair, closely gauging my response. Indulging him, I looked at the photo again. The blue eyes, the over-exposed face, the smile that wasn’t really a smile. Perhaps she did look familiar now. ‘I don’t know. I’m sorry. Who is she?’

‘Her name is Sammy Went. This photo was taken on her second birthday. Three days later she was gone.’

‘Gone?’

‘Taken from her home in Manson, Kentucky. Right out of her second-floor bedroom. Police found no evidence of an intruder. There were no witnesses, no ransom note. She just vanished.’

‘I think you’re looking for Edna,’ I said. ‘She teaches Crime and Justice Studies. I’m just a photography teacher but Edna lives for all this true crime stuff.’

‘I’m here to see you,’ he said, then cleared his throat before continuing. ‘Some people thought she wandered into the woods, got taken by a coyote or mountain lion, but how far could a two-year-old wander? The most likely scenario is Sammy was abducted.’

‘… Okay. So, are you an investigator?’

‘Actually, I’m an accountant.’ He exhaled deeply and I caught the smell of spearmint on his breath. ‘But I grew up in Manson and know the Went family pretty well.’

My class was set to start in five minutes so I made a point of checking my watch. ‘I’m very sorry to hear about this girl, but I’m afraid I have a class to teach. Of course I’m happy to help. What kind of donation did you have in mind?’

‘Donation?’

‘Aren’t you raising money for the family? Isn’t that what this is about?’

‘I don’t need your money,’ he said with a chilly tone. He stared at me with a pinched, curious expression. ‘I’m here because I believe you’re … connected to all this.’

‘Connected to the abduction of a two-year-old girl?’ I laughed. ‘Don’t tell me you came all the way from the States to accuse me of kidnap?’

‘You misunderstand,’ he said. ‘This little girl disappeared on April 3rd, 1990. She’s been missing for twenty-eight years. I don’t think you kidnapped Sammy Went. I think you are Sammy Went.’

There were seventeen students in my photography class, a mix of age, race and gender. On one end of the spectrum was Lucy Cho, so fresh out of high school she still wore a hoodie with Mornington Secondary emblazoned on the back. On the other end was Murray Palfrey, a 74-year-old retiree who had a habit of cracking his knuckles before he raised his hand.

It was folio presentation night, when students stood before the class to display and discuss the photos they’d taken that semester. Most of the presentations were unremarkable. The majority were technically sound, which meant I was doing something right, but the subject matter was largely the same as the folios in the previous semester, and the one before that. I saw the same graffiti on the same dilapidated brick wall; the same vine-strangled cabin in Carlton Gardens; the same dark and spooky storm drain dribbling dirty brown water into Egan River.

I spent most of the class on autopilot.

My encounter with the American accountant had left me rattled, but not because I believed what he said. My mother, Carol Leamy, was a lot of things – four years dead among them – but an abductor of children she was not. To spend one minute with my mother was to know she wasn’t capable of maintaining a lie, much less international child abduction.

James Finn was wrong about me and I was fairly certain he’d never find that little girl, but he had reminded me of an uncomfortable truth: control is an illusion. Sammy Went’s parents had learned that the hard way, with the loss of a child. I had learned it the hard way too, through the death of my mother. She went suddenly, relatively speaking: I was twenty-four when she was diagnosed with cancer and twenty-six when it killed her.

In my experience most people come out of something like that saying one of two things: ‘everything happens for a reason’ or ‘chaos reigns’. There are variations, of course: ‘God works in mysterious ways’ and ‘life’s a bitch’. For me, it was the latter. My mother didn’t smoke or spend her working life in a textiles factory. She ate well and exercised, and in the end it made exactly zero difference.

See, control is an illusion.

I realised I was daydreaming my way through the folio presentations so I downed a cup of cold coffee and tried to focus.

It was Simon Daumier-Smith’s turn to show his work. Simon was a shy kid in his early twenties who spent most of his time staring at his feet when he talked. When he did look up, his lazy eye bobbed around behind his reading glasses like a fish.

He spent a few minutes awkwardly setting up a series of photos on the display easels at the front of the class. The other students were starting to get restless, so I asked Simon to talk us through the series as he set up.

‘Uh, yeah, sure, okay,’ he said, struggling with one of the prints. It escaped from his hand and he chased it across the floor. ‘So, I know that we were meant to look for, uh, juxtaposition and, uh, well, I’m not exactly sure I have, you know, a grasp of what that is or whatever.’ He placed the last photo on the easel and stepped back to let the class see. ‘I guess you could say this series shows the juxtaposition of ugliness and beauty.’

To my complete surprise, Simon Daumier-Smith’s photo series was … breathtaking.

There were six photos in total, each framed in the exact same way. He must have locked the camera off with a tripod and taken a photo every few hours. The composition was stark and simple: a bed, a woman and her child. The woman was Simon’s age, with a pockmarked but pretty face. The child was around three, with unnaturally red cheeks and a sick, furrowed brow.

‘I took them all over one night,’ Simon explained. ‘The woman is my wife, Joanie, and that’s our little girl, Simone. We didn’t name her after me, by the way. A lot of people think we named her after me, but Joanie had a grandma called Simone.’

‘Tell us more about the series, Simon,’ I said.

‘Right, uh, so Simone was up all night with whooping cough and I guess she was pretty fussy, so Joanie spent the night in bed with her.’

The first photo showed mother spooning child. In the second the little girl was awake and crying, pushing away from her mother. The third looked as though Simon’s wife was getting fed up with her photo being taken. The series went on like that until the sixth photo, which showed both mother and child fast asleep.

‘Where’s the ugliness?’ I asked.

‘Well, uh, see in this one, little Simone, ah, the younger subject, is drooling. And obviously you can’t tell from the photo, but in this one my wife was snoring like crazy.’

‘I don’t see ugliness,’ I said. ‘I see something … ordinary. But beautiful.’

Simon Daumier-Smith would never go on to become a professional photographer. I was almost certain of that. But with his plainly named series, Sick Girl, he had created something true and real.

‘Are you alright, Miss Leamy?’ he asked.

‘It’s Kim,’ I reminded him. ‘And I’m fine. Why do you ask?’

‘Well, you’re, uh. You’re crying.’

It was after ten when I drove home through the gloomy landscape of Coburg. Rain fell in fat, drenching sheets against the roof of the Subaru. Ten minutes later I was home, parked, and dashing through the rain toward my apartment building, holding my bag over my head instead of an umbrella.

The third-floor landing was thick with the smell of garlic and spice; the oddly comforting scent of neighbours I’d never actually met. As I headed for my door, Georgia Evvie from across the hall poked her head out.

‘Kimberly, I thought that was you.’ She was a rotund woman in her early sixties with bloodshot, bleary eyes – ‘Heavy Evvie’, I once heard a neighbour call her behind her back. ‘I heard the elevator ding and looked at my watch and thought, who else would be coming home this close to midnight?’

It was ten-thirty.

‘Sorry, Mrs Evvie. Did I wake you?’

‘No, no. I’m a night owl. Of course, Bill’s in bed by nine so he might have stirred but he didn’t complain.’ She waved a dismissive hand. ‘And if he did I’d have reminded him you’re young. Young people come home late nowadays, even on weeknights apparently.’

‘Uh huh.’

Nobody had ever actually seen Georgia’s husband and there was little to no evidence he truly existed. Of course, he might have just been buried under all of Georgia’s crap. From the glimpses I caught of her apartment when she came to her door, I knew that 3E was lined with swaying towers of junk: books, bills, files and over-stuffed boxes. The only window I could see from the hall was covered with newspaper, and although I never actually saw one, I’m sure there were one or two tinfoil hats floating around in all that chaos.

‘Well, seeing as how you’re already awake …’ she started. Georgia was about to invite herself in for a nightcap. All I wanted was to turn the heat up, lounge on the sofa with Stephen King and listen to the soothing, predictable sounds of my apartment – the hum of the refrigerator, the whisper of ducted heating, the quiet buzz of my laptop charger. ‘… how about a nightcap?’

With a sigh I said, ‘Sure.’ Ever since my mother’s death I’ve found it near impossible to say no to a lonely woman.

My one-bedroom apartment was sparsely furnished, giving the impression that the place was huge. Even Heavy Evvie looked small sitting in the green armchair by the rain-streaked window of the living room, picking lint from her tracksuit pants and dropping it onto my hardwood floor.

I fetched a bottle of wine from the kitchen and fixed us both a glass. The one good thing about having Georgia over was I didn’t have to drink alone.

‘What do you think they’re cooking up over there, Kim?’ she asked.

‘Who?’

‘Who do you think? 3C. I hear them chattering all day in Iraqian or whatever.’

‘Oh, 3C. Smells like some kind of curry.’ My stomach growled. I had searched the kitchen for something to eat but all I could find were condiments. Wine would have to suffice.

‘I’m not talking about their supper.’ She lowered her voice to a whisper: ‘I’m talking about their plan.’

Georgia was convinced the occupants of 3C were terrorists based on two things: they were from the Middle East, and the name on their mailbox was Mohamed. On a number of occasions I’d explained to her that not all people with light-brown skin were terrorists and, regardless, I doubted Coburg, Australia would rate high on anyone’s list of targets. But every time, Georgia just shook her head gravely and said, ‘You’ll see.’

‘So what brings you home so late, Kim? I suppose you’ve been out clubbing.’

‘I work nights, Mrs Evvie. You know this.’

She sipped her wine and screwed her nose up at the taste. ‘I don’t know how you kids do it. Out all hours doing God knows what.’

I finished my wine fast and poured another one, reminding myself to take slower, more contemplative sips this time around. I was only after a warm, foggy buzz that would make it easier to sleep.

‘So something weird happened to me tonight, Mrs Evvie,’ I said. ‘A man approached me at work.’

‘Finally,’ she said, helping herself to more wine. ‘It’s about time, Kim. A woman only has a small window to bag a man. Between fifteen and twenty-five. That’s all you get. I was seventeen when I met Bill, eighteen when I married him.’

Georgia found a remote control stuffed between the green cushions of the armchair and turned on the television. Tinfoil hat and casual racism aside, all she really wanted was some company.

I curled up on the sofa nearby and opened up my laptop while she flicked through the stations at full volume.

I had intended to casually browse the internet, maybe stalk a high-school friend or purge my email inbox, but my curiosity soon grew too strong. When I opened a new tab and searched Sammy Went + Manson, Kentucky, it was as if my fingers were acting independently. It reminded me of the mechanical way James Finn had moved his manila folder about.

The first link took me to an archived newspaper article from 7 April 1990. The article had been electronically scanned in, complete with creases and inkblots. The words bled together in places, making me feel like an old-timey researcher poring through microfilm.

POLICE SEARCH FOR MISSING GIRL

The search for a two-year-old girl missing in the Manson area resumed on Friday with volunteers and law enforcement officers.

Sammy Went of Manson disappeared from her home Tuesday afternoon and has not been found despite a search of the town and its vicinity.

‘We have faith we’re going to find Sammy and bring her home safe,’ Manson Sheriff Chester Ellis said. ‘We’re currently working under the assumption this is a search and rescue operation.’

Police do not believe the girl’s disappearance was the result of foul play, but refused to rule anything out.

Hundreds of Manson residents searched the extensive wooded areas surrounding the Went residence on Friday.

Search volunteer Karen Peady, a long-time resident of Manson, expressed her fears: ‘The nights are cold and there are a lot of wild animals in the area, but the idea she was taken by a man is what scares me the most. It’s tempting to think the evils of modern America haven’t reached us out here in Manson yet, but there are plenty of sick people in this world, even in a town as small as this.’

Sammy was last seen wearing a long-sleeved yellow T-shirt and blue pyjama shorts. Police are asking for any information that may assist their investigation.

The article was accompanied by the same photo that James Finn had shown me, only this version was in black and white. Sammy’s deep blue eyes appeared black, and her over-exposed face was stark white and mostly featureless.

A little more internet research took me to a photo of Jack and Molly Went, Sammy’s parents. The picture had been taken in the days directly following Sammy’s disappearance, and showed them standing on the steps outside the Manson Sheriff’s Station.

They looked desperately tired, faces tense, fear etched in their eyes. Molly Went in particular looked permanently damaged, as if her spirit had left the body to run on autopilot. Her mouth was twisted into a frown so severe it made her look deranged.

Tracing her features on the screen, I compared Molly Went’s face to my own. We shared the same long, angular nose and droopy eyelids. She seemed much shorter than me, but Jack Went looked well over six foot. The harder I looked the more I could see myself in both of them: Jack Went’s small, pale ears, Molly Went’s posture, Jack’s broad shoulders, Molly’s pointed chin. A little DNA from column A, a little from column B.

Of course, that didn’t mean anything. I feel the same way when I read horoscopes – they’re designed to allow the reader to see what they want.

Do I want to see myself in Jack and Molly Went? I wondered. The question came to me by surprise and soon my mind was buzzing with more. Hadn’t Sammy’s eyes been the same deep blue as mine, and couldn’t those chubby legs of hers have transformed into long skinny pegs like my own, and if Sammy were alive today, wouldn’t we be roughly the same age?

Were Jack and Molly Went still waiting for answers? Did every phone call or knock at the door fill them with hope or dread or some bitter mixture of both? Did they see Sammy’s face in every woman they passed on the street, or had they found a way to move on?

The biggest question of all came like a shard of glass to my consciousness: could Carol Leamy, a woman with a background in social work who spent most of her working life as an HR rep for a company that sold and manufactured picture hooks, really, honestly, ever be capable of—

I stopped myself from going any further. The implications were too great and, frankly, too absurd.

The sound of heavy snoring pulled me from my laptop. Georgia had fallen fast asleep in the green armchair, her glass of wine balanced precariously between thumb and forefinger. I took the wine, switched off the television and covered her legs with a fluffy red throw rug. If history was any guide she’d be asleep for a few hours. She’d then wake around three am to use the toilet before waddling back across the hall.

Leaving Georgia where she was, I crept into my bedroom and climbed into bed. When I fell asleep, I dreamed about a tall man made entirely of shadows. The shadow man appeared outside my bedroom window and reached in with impossibly long arms. He carried me away, down a long, narrow dirt path lined with tall trees.