Читать книгу The Nowhere Child - Christian White - Страница 9

MELBOURNE, AUSTRALIA Now

ОглавлениеMy sister’s townhouse was in a labyrinth of identical-looking homes in Caroline Springs. I’d been there at least a dozen times already but I wasn’t sure I had the right place until Amy rushed out to meet me.

‘What is it?’ she called. ‘What’s wrong? What’s going on?’

‘What are you talking about? Nothing’s wrong. Who said anything was wrong?’

She bent over at the waist and braced herself on her knees, heaving with melodramatic relief. ‘When I saw you out front I just … I didn’t know you were coming and … I’m sorry. I guess I have a habit of assuming the worst.’

‘Yikes. Can’t a girl just visit her sister?’

‘Not when that girl is you, Kim. You’re not exactly the pop-in type.’

I made a big show of rolling my eyes because I didn’t want her to know she was right – which, of course, she was. I’m generally solitary by nature. I feel much more comfortable alone, staying in and reading a book or wandering the aisles of the supermarket for an hour trying to find the perfect brand of linguine.

Amy was five years younger than me, with a warm, round face and full body. ‘Bumps in all the right places’, our mother used to say. It was as if my sister’s genes had defined themselves in opposition to my own. Nobody in school ever stopped her to say, ‘Excuse me but I think your boobs are on backwards.’

Technically Amy and I were only half-sisters. Her father (my stepdad) met my mother when I was two, and they had Amy when I was five. But blood and DNA aside, there was no half about it. Amy was my sister, for better or worse.

Dean had been around long enough to earn the position of official, bona fide Dad. Of course, never knowing my real father meant there was no basis for comparison.

‘Aunty Kim!’ Lisa, my three-year-old niece, had hurried out through the open front door and onto the lawn, two fingers wedged into her mouth. The grass was wet and her socks were immediately soaked through, but that didn’t slow her down. She crossed the lawn as fast as she could. I grabbed her under the armpits, hoisted her into the air and turned her upside down. She screamed in delight, giggling until snot came out of her nose.

I set Lisa down on the front step and let her run into the house, her wet socks leaving tiny footprints on the hardwood floors. As usual, the house was a mess. Dishes were piled six plates high in the sink, Lisa’s toys were strewn up and down the hallway, and the living-room sofa was covered with coloured crayon, its creases foaming with forgotten chalk and food crumbs.

The television, a brand new fifty-two-inch, was blaring at full volume. Lisa was lured to it like a zombie. She stopped less than a foot from the screen, mouth agape, as if the cartoon characters on the screen were whispering all the secrets of the universe.

In the middle of the living-room floor was an Ikea box, roughly torn down the middle to expose a mad tangle of cheap wood and plastic brackets.

If I spent just one day in Amy’s shoes my mind would melt with sensory overload, but she seemed to thrive in the chaos.

‘It’s a goddamn toy chest for Lisa’s room,’ she said, picking up an L-shaped bracket and turning it over in her hands, as if it were some mysterious archaeological artefact. ‘Or at least it will be a toy chest … one day. In the far off, distant future.’

‘Need some help putting it together?’

‘Nah, I’ll leave it for Wayne to finish. And I don’t even care what that says about me as a woman. Coffee?’

‘Sure.’

As she prepared coffee in the adjoining kitchen, she talked about the toy chest for a full five minutes. Shouting over the sound of the percolator, she told me how much the toy chest cost, which section of Ikea she found it in, what it should look like after its construction and the complex series of decisions that led to its purchase. She told me all of this without a break as I waited in the living room. I could have left, gone to the bathroom and come back, and she wouldn’t have noticed. Instead I used the time to scan her bookshelves, searching for her photo albums.

In particular I was looking for a fat pink folder with EARLIEST MEMORIES spelled out in purple block letters on the cover. The album had belonged to our mother, and should really have been kept at Dean’s place, but Amy went a little nutty with photos after Mum died.

The photos were the whole reason I was here. Last night I’d half-convinced myself that I could have been the kid in James Finn’s photograph, and I was eager to knock that speculation on the head.

The bookshelf was packed with DVDs, magazines, a framed cast of two tiny feet marked Lisa, age 6 months, but there were no albums.

‘What are you looking for?’ Amy had snuck up behind me. She handed me a cup of black coffee. ‘We’re outta milk.’

‘That’s fine. And nothing. I was just looking.’

‘You’re lying.’

Damn it, I thought. Ever since we were kids Amy could always tell when I was trying to hide something. She had a knack for it that bordered on psychic. The morning after I’d lost my virginity to Rowan Kipling I told my parents that I had stayed over at my friend Charlotte’s place. Amy, at all of eleven years old, looked at me over her breakfast cereal and said, ‘She’s lying.’

Assuming Amy knew something they didn’t, Mum and Dean started picking at my lie until the whole damn story came unravelled. It wasn’t that I was a bad liar; Amy was just an exceptional lie detector.

Sighing, I came clean. ‘I’m looking for the photo album with the baby pictures.’

Amy clicked her tongue, a thinking technique she’d used since she was a kid. The wet click-click sound briefly transported me back in time to my bedroom at number fourteen Greenlaw Street. The memory was hazy and fragmented, lacking context like a fading dream. But I could see Amy clearly, at four or five years old, in pink-and-green striped pyjamas. She was climbing into my single bed and I was pulling back the covers to let her in.

As the memory drifted away a heavy sadness remained.

‘All the photos are probably in the garage someplace,’ Amy said. ‘We still haven’t totally unpacked the garage, if you’d believe it. Six months later. It’s Wayne’s job but every time I bring it up he does this big sigh. You know that sigh he does that sounds like a deflating tyre? Like you just asked him for a kidney.’

‘So you have it?’

‘Why do you want it?’

‘This’ll sound strange, but it’s a secret.’

Amy sipped her coffee, searching my face for whatever hidden tell or psychic signal she usually used to catch me out. Then her eyes lit up. ‘Does this have something to do with my birthday? Did Wayne tell you about the photo collages we saw at the shopping centre? Forget it. Don’t tell me. I want it to be a surprise. Follow me.’

The garage smelled of old paint and methylated spirits. Amy found a pull-string in the darkness and a fluorescent light flickered on overhead, revealing a cramped concrete room with a low ceiling.

Several rows of packing boxes occupied the space between the far wall and Amy’s little red Honda Jazz. We spent the next forty minutes carrying out each box, setting it down on the small patch of unused concrete floor and poring through its contents.

Most boxes contained miscellaneous stuff: year-old energy bills, a roll of expired coupons, a tattered apron, a chipped ceramic ashtray with a single English penny sliding around inside, a grocery bag full of magnets that Amy snatched gleefully from my hands saying, ‘I’ve been looking for these.’

One of the boxes was full of my old photography projects, many embarrassingly similar to the ones my students had presented the night before. I found a first-year uni photo-series called Scars: Physical and Emotional. Amy had organised the collection into a binder. I flicked through it, cringing; it was more like a high school project than a university folio.

One photo showed the small nick I got on my pinkie toe while climbing out of a friend’s pool one summer; another showed the grizzly slice running across Amy’s thigh from when she fell off her ten-speed. Here was a nasty burn on my mother’s hand, and the fading ghost of an old housemate’s cleft palate. Next came several photos showing subjects who looked sad or rejected or angry. It was a pretentious, highly unoriginal project designed to force the audience to consider the scars people carry on the inside as well as on the outside.

‘Oh, hey, how’s it going with Frank?’ Amy asked, leafing through an old school report.

‘Eh.’

‘What’s that mean?’

‘We stopped seeing each other.’

‘Why?’ Amy said in a high-pitched, whining voice.

‘No one thing. Just, you know. It wasn’t a love connection.’

‘You’re too fussy, Kim. You know that. And you’re running out of time to make babies.’

Amy was aggressively maternal. Reproducing was her sole purpose in life. She and her fiancé Wayne pumped out Lisa as fast as they could and were planning for a second. I, on the other hand, had never once felt the urge to procreate.

We eventually found the family albums in the ninth or tenth box and sat cross-legged on the floor to look through them. Each album was titled with big block letters, written in colours that somehow matched the theme of the photos within. PERTH HOLIDAY ’93 was black and yellow to match the emblem on the state flag. NEW HOME, which chronicled Mum and Dean’s move from their old place on Osborne Avenue to their smaller but much newer pad on Benjamin Street, was written in blue and green: the blue matched the porch steps of Osborne, the green matched the bedroom walls of Benjamin. The humorously named OUR FIRST WEDDING was written in bright orange – the same shade my mother wore on the big day.

It’d be easy to assume that my mother was the one who meticulously matched each colour and labelled each photo, but it was Dean. Even before our mother died he obsessed over photographing, categorising and recording each and every memory for safekeeping.

Amy grabbed the wedding album the second she saw it. With a sad smile she turned the pages, tracing our mother’s face.

At the bottom of the box I found the fat pink baby album, EARLIEST MEMORIES, written in the same shade of purple as my childhood headboard. Inside were photos of birthday parties, holidays, Christmases; all lost to time. There was a picture of me in the old flat we lived in before Amy was born: smiling broadly, framed against the ugly yellow wallpaper that lined every single room. Another showed my first day of kindergarten, my mother holding my hand and grinning.

A third of the way through I came across a bright, pudgy little girl staring at me through the plastic sleeve. She was standing in the shallow end of a hotel pool, dressed in sagging yellow bathers. She looked somehow contemplative and wise. Below the shot, printed in neat black letters was, Kim, age 2. I had a vague memory of that day in the pool, riding Dean’s shoulders into the deep end.

The remaining pages were blank. There were no baby photos, and nothing else before the age of three. I hadn’t been expecting more. My biological father wasn’t a nice man – that’s how my mother had phrased it on one of the few occasions we discussed him. When she had left him she left in a hurry, a toddler under one arm and an overnight bag slung over the other, with no time and no room for baby pictures. That story sounded worryingly convenient now.

‘Are you okay?’ Amy asked. ‘You look like you’ve seen a ghost.’

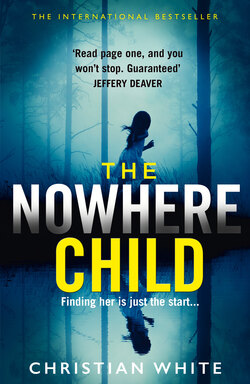

In a way I had. Suddenly the ghost of Sammy Went was haunting each and every childhood photo. Even before I brought up a photo of Sammy on my phone I could see it was more than just a passing resemblance. The deep blue eyes, the dark hair, the tight-lipped smile, the curved chin, the large nose, the small white ears. It wasn’t just uncanny; either Sammy was my exact doppelgänger, or I was looking at photos of the same girl.

Why hadn’t I seen it before? Was it simply that I couldn’t remember what I looked like as a kid, or had I not been ready to see it? Was I ready now?

‘Jesus, Kim, what is it?’

‘Amy, I came here to compare photos from when I was a kid to a little American girl who went missing in the ’90s.’

‘Hold up. So you’re not making me a photo collage for my birthday?’

I closed my eyes, took a deep breath and started from the beginning. Sitting cross-legged on the floor of the garage, surrounded by packing boxes and the smell of old paint and methylated spirits, I opened up the Sammy Went door and invited Amy inside.

She listened silently with a cool expression that gave nothing away. When I had finished she sat blinking like an owl; buffering. Then she laughed. It wasn’t a chuckle or giggle, but a heavy ha ha. She put one hand against her belly, threw her head back and cackled, guffawed, snorted. ‘So let me get this straight: you think Mum – the woman who bawled her eyes out when the horse died in The Neverending Story – was a kidnapper. And you were the kid she napped? She abducted you from someplace in the States and raised you as her own. And never once, not even on her deathbed, revealed the truth.’

‘I don’t know, I …’

‘Maybe she bought you on the black market. Makes perfect sense when you think about it. Oh, or maybe she lowered herself down to your cot on one of those wire harness things like Tom Cruise or trained a dingo to—’

I showed her my phone. She froze, silenced by the photo of Sammy Went on the screen. She took the phone from me and stared, her smile quickly fading. ‘Shit, Kim.’

‘Yeah. Shit.’

‘What did this guy say, exactly?’ She was squeezing the phone so hard I thought it might shatter. ‘How did he find you? What evidence does he have?’

‘I don’t know. I didn’t really give him time to tell me. I thought he was a nutter.’

After a string of increasingly exasperated expletives, Amy said, ‘Do you wanna smoke a joint?’

We left Lisa inside watching TV and sat together on the back step. Amy’s yard was small and well-manicured. A blue plastic sandbox had filled with rainwater, turning the sand inside to sludge. The flat grey walls of the houses on either side of Amy’s fence blocked out half the sky.

She lit the joint and took a long, deep drag before handing it to me. ‘It’s a scam. That’s what it is.’

‘How would that work?’ I said. ‘He didn’t ask me for money or personal details or—’

‘Just you wait. He probably stole that photo.’

‘Neither of us has ever seen it before.’

‘So he, I don’t know, took it.’

‘Twenty-eight years ago? When I was two? And he’s just been, what? Biding his time to pull off the longest sting in history?’

‘Is Mum abducting you from a foreign country a more plausible explanation? Something like this, if it was real … Jesus, Kim. It would fuck everything up. We wouldn’t be sisters anymore.’

The joint sent me into a momentary coughing fit, but it helped dull my busy mind. ‘Don’t be ridiculous.’

‘Kim, if we didn’t have blood connecting us I’d never see you. When you dropped around today it nearly gave me a heart attack. I thought something was wrong.’ She took the joint back. ‘And shit, I guess I was right after all. You weren’t just popping in, were you? You were gathering evidence.’

‘Please don’t turn against me,’ I said. ‘Not right now.’

Amy sighed.

Smoke danced and swirled, making my eyes water.

‘Wayne will still be able to smell this, you know,’ I said.

‘If ever I had a good excuse to get stoned, it’s today.’ She wiped her eyes. I couldn’t be sure if it was the smoke that was making her cry, or the situation. She stared off over the back fence. Another townhouse lay beyond it, and another one beyond that.

She shifted her weight and studied her chipped nail polish, looking anywhere but at me.

‘What do you want me to do?’ I asked.

‘Nothing, Kim. I want you to do nothing. Delete that photo off your phone. Delete his number. Forget about the whole thing.’

‘I don’t think I can do that.’

‘I think you have to, Kim. If you follow this thing through, then everything is going to change.’

‘Okay,’ I said.

‘Swear?’

‘Swear.’

After leaving Amy’s house, I pulled the car to the side of the road and found the number James Finn had given me. I quietly hoped he wouldn’t pick up, but he answered on the first ring.