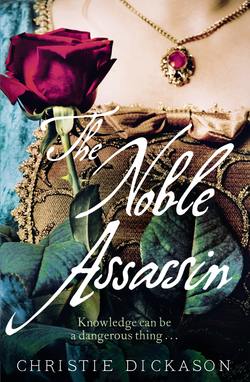

Читать книгу The Noble Assassin - Christie Dickason - Страница 15

ОглавлениеChapter 8

My husband continues to eat slowly and calmly, to show everyone who rules in this house. But he eats without appetite. He still watches me, with the progress of his thoughts clear in his eyes.

He had seen. He had noticed. He feels the change in me and doesn’t know what to do. I almost pity him in his confusion.

Everyone waits for his response while they pretend to eat. By rights, he should assert his male authority. Perhaps even try to beat me later.

But he does not know what to do and hates himself for not knowing. He hates me for making him not know.

His eyes shift away. I have long suspected and am now certain. He is afraid of me. Just as he had once feared his formidable father.

Poor, poor Edward, I think.

Whatever manhood he ever had seems to have leaked away through his cracked arm bone, along with his youth and any vitality, as if the crack had let in a sense of death. The tree trunk that met his head had not cracked his skull, but it seemed, nevertheless, to have shaken his wits.

After the horse threw him, he had surrendered himself to becoming clumsy and lop-sided. He seemed to aim at the world askew, anticipating dislocation and, therefore, finding it.

At first, I had tried to coax him into healing. ‘It’s only an arm,’ I said. ‘Not your neck, or back. It will soon mend.’

‘What do you know of twisted sinews and constant aches that gnaw at your spirits?’

I had bitten back my impatient reply and offered him the cup of pain-killing draught.

Now he gives up on eating, shoves away his plate and stands up from the dinner table. Everyone else stands. He lifts a foot, then hesitates.

I recognise that hesitation. He lurches forward. Looks around. Everyone pretends not to see.

His secretary, his steward, his three attending gentlemen, and all the rest, stand politely, waiting to see what he will do, or wish them to do.

A show of respect for his position, I think. Not for the man.

Every year since his accident, the Earl shrinks a little more. Everything grows less. His movement, his appetites, his will. His fortune. His dignity. The space he occupies in this world.

He looks at me accusingly, as if I had caused the floor to shift beneath his feet.

I have to look away. I cannot bear his wilful determination to suffer.

On the last time that we truly spoke to each other, he had pointed at me with his good hand. ‘I stumble towards the grave,’ he had said. ‘I’m dying, and no one on this earth cares that I am afraid of death yet wish for it at the same time – least of all you, who should care most of all. My wife.’

‘You’re not dying,’ I said. ‘You can walk. And you could ride again, if only you would.’

‘What do you know of suffering?’

I could only look at him, wordless.

‘Get out of my sight,’ he had said. ‘Stop taunting me with your lithe moves and your sudden little dance steps.’ His gaze had fallen on the ridged mud plot outside the window, a frozen maze of ditches and string, which would one day become my new garden. ‘Go look for joy out there in the mud you love so much.’

Unless I shared in his misery, I insulted him with any pleasure I took in life.

‘And in case you hope to make a life without me here in this godforsaken place,’ he said, ‘I will tell you that no one of any consequence will ever come see your blasted garden!’ He steadied himself against the tabletop, waving away my offered hand. ‘What good do you imagine that making a garden has ever done anyone?’

He turned his face away from the window, squinting his eyes as if hurt by the light.

‘I know that you hide from me out there, amongst all those costly infant trees we can’t afford. I’ve seen you wrapping them tenderly against the cold. And when it’s too cold to coo over trees or seedlings in some gardener’s hands, you bury yourself away from me making sketches and diagrams. You make your garden only to torment me, to punish me for what I have become, even though it was not my fault.’

I had stood wordless, unlike my usual self, my breath taken away by this mistaking of the truth, and from fear of what I felt coming.

‘How dare you imply reproach, as if I were a useless husband?’ His knuckles whitened on the edge of the tabletop. ‘I lifted you from country into court. And to no purpose! You have killed my family’s line. You can’t even produce me a living heir!’

I keep my eyes averted now until I hear him move away from the table. I watch him leave the hall. He walks uncertainly, as if unsure where to go. His two gentlemen of the bedchamber, the sons of neighbouring knights, exchange glances then follow him. I see his old nurse hobble to meet him in the passage outside the hall, take his good hand and lead him away to the safety of her care.