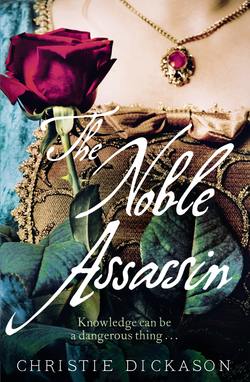

Читать книгу The Noble Assassin - Christie Dickason - Страница 8

ОглавлениеChapter 1

LUCY – MOOR PARK, HERTFORDSHIRE, NOVEMBER 1620

The air is so cold that I fear my eyelashes will snap off like the frozen grass. Only my two youngest, most eager hounds have left the fireside to bound at my side.

I do not want to die. But I cannot go on as I am, neither. I ride my horse closer to the edge of the snow cliff. I imagine turning his head out to the void and kicking him on. I imagine the screams behind me.

We would fly, my horse and I, falling in a great arc towards the icy River Chess far below. My hair would loosen and tumble free. His tail and my darned red gown would flutter like flags.

Then we would begin to tumble, slowly, end over end, like a boy’s toy soldier on horseback, my bent knee clamped around the saddle horn, his legs frozen in mid-gallop. The winter sun reflecting off his black polished hoofs. My last unsold jewels scattering through the air like bright rain. For those frozen dreamlike moments, my life would again be glorious.

I feel the alarmed looks being exchanged behind me on the high, snowy ridge, among the moth-eaten furs and puffs of frozen breath. I quiver like a leashed dog, braced for the first voice to cry, ‘Take care!’

I walk my horse still closer to the edge.

It would be so easy.

I look down again at the river. Why not? What is left to lose now?

The in-drawn breath of that vast space pulls at me. The serrated edges of the snow cliff glisten, sharp enough to slice off Time.

Welcome, the space whispers. Below me, I see the smiling faces of my two dead babes. Welcome. I see the face of my poet, my only love, now dead to me.

One kick, then no more fighting. No more debts. No more loss. No more of the scorn and silence already denying that I am alive.

Even my Princess is gone from England.

I listen to the uneasy stirring behind me. Who would break first and call me back?

You can die from lack of a purpose to live.

‘Your Grace . . .’ The waiting gentleman speaks quietly lest he startle me, or my horse, and send us over the edge. Speaking carefully, as if I were poor, maimed, self-indulgent Edward, who suffers so nobly before witnesses then beats his fist against his chair when he thinks himself alone.

The cold air is a knife in my chest. The sun on the snow blinds me. I am made of ice.

I let my small band of attendants hold their breaths by the edge of the snow cliff. They should be grateful to me for this small gift of fear, I think. Salting the bland soup of their day.

I look down at the river again. Edward is wrong to say that I lie to myself. I face the reality in front of me. Listen to its melody. Then I rewrite it, sometimes on paper, sometimes only in my head. I give it more beauty, or terror or meaning. I tell the story better. But I never deceive myself as to which is which.

For instance, I can see that the scene I am now writing in my head is impossible. The fall would be messy, not glorious. Almost certainly, the horse would have to be shot. I would land at the bottom broken but still breathing. And then I would become a captive with my husband in his fretful rage.

I see the pair of us, invalids side-by-side in our fur rugs, dropping malice as the stars drop the dew until we die.

I still brim with unwritten words, unsung music, unplanted gardens. I still keep most of the looks and all of the wit that had made me the darling of the Whitehall poets. I feel like a piece of verse begun but not finished. There is one poet who could have written me but never will.

In the void below me, I see him striding up and down the gravel path of my lost garden in Twickenham, stirring the air, reciting a poem born from the passionate union of our thoughts. I hear words I had offered him, whole lines, even. An easy rhythm where my ear had pointed out a stumbling line for him to revise. All now made his own. He recites the completed poem for the first time, to me alone, too intent to notice that spray from the fountain spangles his dark hair and coat with sparkling diamond chips.

He glares up at the sky and down at the gravel path. I watch his clenched hands spring open to mark each stress of his metre. Watch his long fingers and feel them on my skin. His words sail out of his body on the fierce current of his breath into the wide air of the universe. I imagine them sailing on past the moon, past the sun, until they reach the farthest heavens to lodge as new stars. He comes to the end of the poem, listens for a moment to its last echo in his head, then turns to look at me, almost with fear. Was it good?

I have lost him along with all the rest.

When I had been the Queen’s favourite, she bathed me in her generosity. Passing it on with an open hand, I became that bountiful goddess known as a patron, a source of prizes, favours and preferment.

But my fortunes had declined with the Queen’s health and the vigour of her court. My husband and I never recovered from his fine for treason. I often spent what I did not have. Our growing debts had forced me to sell the lease of my Twickenham garden to that reptile Lord Bacon. When the Queen died, almost two years past, I was finished. Her court was dissolved. I lost my place and the wealth that went with it. I could no longer afford to be patron, to my poet or anyone else. Now I am branded a ‘court cormorant’, a beggar, wife of a debtor, a woman of no use to anyone, burying her shame in the country. Like the pox, my fall from grace threatens to infect others.

What remains for me? Why not open my wings and fly? If not here, somewhere higher and more certain.

My gelding suddenly shies away from the shining ice edge.

I lean forward and pat his neck. ‘Don’t fear,’ I murmur. ‘When I jump, I won’t take you with me. I swear it. Nor anyone else.’

Not today.

But I have never yet given up on anything I set my mind to.

I will do it, I promise myself. Soon.

My poor hounds have begun to shiver, up to their shoulders in the drifts.

I turn my horse’s head to let him begin to pick his way back down along the icy track towards Moor Park, with the dogs racing ahead and my attendants behind, no doubt relieved. I press my old beaver muff to my cold face then bite savagely into the fur like a hound on a hare’s nape.

I have little patience with wilful misery, least of all my own, but I see no way out for me now. I clench my teeth on the side of my hand, deep inside the muff. I want to throw back my head and howl. To crack open the steady deadly progress of time and set loose demons and angels with flaming swords. I would welcome the novelty of a second Great Flood, cheer on the Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse. Anything to change what my life has become.

When I drag my frozen skirts back to the fire in the hall at Moor Park, I learn that those demons and angels have already escaped. As my skirts steam and drip and my shivering grey hounds curl close to the flames beside their fellows, I listen with horror to Edward’s urgent report.

The dark, gaunt Horseman of War had heard my desperate plea.

‘There is war in Bohemia.’ My husband can scarcely conceal the pleasure he takes in telling me.

I didn’t mean it! I think. Not like this! Not Elizabeth!

‘They lasted scarcely a year on the Bohemian throne, your English princess and her little Palatine husband.’ He shakes his head and waits for me to ask if she is dead.

Queen Anne’s daughter Elizabeth. My father’s former charge, raised in our home at Combe Abbey. Elizabeth Stuart, the only woman I love who is still left alive. In spite of her younger years, she could always match me thought for thought. At times, she had left me, the older girl, laughing in her wake.

When I remain silent, he can’t contain himself any longer. ‘All reports say the Hapsburg armies have invaded Prague, routed the new young King’s Protestant forces and arrested the rebel leaders.’

‘How certain is this news?’

‘A courier arrived from my cousin today.’

‘What of the King and Queen?’ I ask when my voice is again under control. My Elizabeth and her Frederick, who had been pressed into accepting the crown of Bohemia.

‘Fled, I’m told . . . and still in flight. Declared outlaws by the Hapsburgs, under Ban of the Empire.’

I want to hit him for the pleasure in his voice. ‘Will England go to war to save her?’

‘That’s for her father to decide.’ I have asked a foolish question. Then he smiles and shrugs. ‘King James is England’s self-styled “rex pacificus”. Draw your own conclusions.’

‘There’d be no honour in his “peace” now.’ I wish I could say that my feelings at that moment are pure, generous and patriotic, but honesty insists otherwise. A sudden jolt of excitement runs through my horror.

‘The Bohemians might prefer to call their leaders “heroes” not “rebels”,’ I say mildly while my racing thoughts drown both Edward’s voice and his quiet malice.

I survived my first seven years of marriage chiefly by pretending to ignore my husband. He had soon proved to be a master of the puzzled tone, the helpless shrug, the meaningful glances over my head. He let my words fall to the floor as if they had no meaning. Or he would seize on one and examine it with puzzled incomprehension before tossing it away. Or he shook his head sadly and told me what I had meant to say. In the company of other men, he ignored me altogether. When he managed to provoke me past endurance, he would smile with satisfaction. Look at her! See what a harridan I have married!

Having once again failed to goad me into an unseemly outburst, my husband now purses his lips. I scarcely notice.

If what Edward tells me is true, I know that the future of England has just changed. My future could change with it. I see escape from Edward and from Moor Park. I see the return of warmth and true companionship. I see purpose for my life again. I confess that I begin to listen to his news of unfolding disaster in Bohemia with a heart turned suddenly light with renewed possibility.