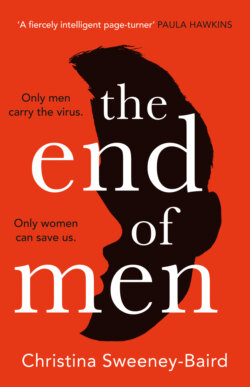

Читать книгу The End of Men - Christina Sweeney-Baird - Страница 12

Amanda Glasgow, United Kingdom Day 9

ОглавлениеIs the beginning of a Plague a good time to get a divorce? Or maybe I should just kill him and avoid the paperwork? Will, the fucking idiot, went to work. He knew not to. I have been so careful.

When I left the hospital on 3 November at the end of my shift I changed out of my scrubs and walked, in my underwear, to the fire exit in the changing room and put on fresh scrubs from the plastic just before I left through the door emblazoned with FIRE EXIT ONLY. I did not give one single solitary fuck about fire exits.

After getting out of the car once I got home, I ignored the front door, stripped in the garage and burned the clothes. I walked naked through the house and showered with the water as hot as I could bear and a new bottle of sterilising scrub wash I took from the hospital store room. I didn’t go near the boys and screamed at them when they started jokingly coming towards me in pigeon steps. Will was incredulous for the first night as I slept in a camp bed in the garage. He went to work the next day despite my telling him on pain of death not to – he left before I woke up – and when he came home, he was white with shock.

‘I believe you,’ he said. Fat lot of good that will do us now, I wanted to scream. He had been exposed unnecessarily. He had gone back to the hospital. The one place in the country with a higher number of infected bodies than anywhere else.

He hadn’t gone to work again. Until yesterday. It had been eight days since the day in A&E when this miserable thing started and he was still fine. The incubation period can’t be more than a few days based on the speed with which men were returning to A&E. We were safe, out of the danger zone just enough for me to sit in the same room as Will and the boys and laugh along to something on Netflix without having a heart attack every time one of them sneezed. My moron of a husband went in to work on 4 November and somehow escaped death and then, a week later, must have decided that life here in this quiet suburb on the north side of Glasgow just isn’t thrilling enough for him.

‘It’s a baby,’ he shouts at me when I finally run out of steam after his return. He was only gone a few hours. ‘She’s going to die if I don’t help. I’m the only paediatric oncologist in the hospital at the moment.’ He doesn’t say why he’s the only paediatric oncologist because he knows it answers my questions for me and makes his arguments absurd. He’s the only paediatric oncologist in the hospital at the moment because the other two fucking died.

‘You have two children here in this house,’ I scream with fury. ‘You might be a better doctor than me but I’m a better parent. I care more about Charlie and Josh than some toddler.’

Will is weeping now. I’ve never made him cry before. It makes the words I want to shout die in my throat. ‘Her mother called me on my mobile. She begged me, she was going to die. No one had given her the chemo in over forty-eight hours. She’s, she’s, I … I just …’ He breaks down into sobs. I so desperately, even through my anger, want to reassure him, hold him and rock him and say it’s OK, no mistake is irreversible, I forgive you.

But this mistake is not reversible. I cannot touch my husband because if he is carrying the virus I might catch it and then our boys will be more likely to get sick. I cannot forgive him if the boys die because of this. A nameless, faceless child in a hospital ward four miles away is not my concern. My boys – Charlie and Josh, with the beginnings of stubble growing across their jaws and hazel eyes and freckles and creased foreheads when they’re concentrating on homework – are my concern. I cannot forgive Will for not putting them first. They are all that matters.

‘Sleep in the garage. Don’t touch anything. Don’t do anything and don’t go anywhere near the boys. If they try to come into the garage scream at them like they’re about to touch a burning hob.’

Will just sobs and nods in response.

‘I love you,’ I say. I remember seeing a woman in A&E a few years ago. She had found her husband hanging from a curtain pole in their bedroom after a vicious fight. She was going into the bedroom to apologise and make up. I never told Will about it but since then, no matter how awful the argument, I’ve always told him I love him before I leave the room. The Plague is making fast work of men. We don’t need to do its job for it.

‘I love you too. I’m sorry.’

I know darling. But I will never forgive you.