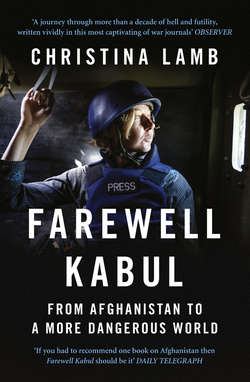

Читать книгу Farewell Kabul: From Afghanistan To A More Dangerous World - Christina Lamb - Страница 15

6 A Tale of Two Generals

ОглавлениеBin Laden may have vanished into the mountains of the tribal areas, but his bony, bearded face was hard to avoid in Rawalpindi, where it stared out from boxes of sweets and posters on sale in the labyrinthine bazaars just a couple of miles from President Musharraf’s house. Right from the start it wasn’t clear whose side Pakistan was really on.

Although Pakistan had been a nominal ally of the US since Pakistan’s creation in 1947, it had never really been a happy marriage. Pakistan had long been ambivalent about the United States, which had poured money and arms in when it needed something – such as help in training and arming the Afghan mujaheddin to fight the Russians during the Cold War – then was never there when Pakistan needed it, such as in its three wars against India.

I always found this combination of Pakistan’s desire to be an American ally with its widespread anti-Americanism confusing. ‘Pakistan’s problem,’ said Husain Haqqani while he was the country’s Ambassador in Washington, ‘is that it is trying to be Iran and South Korea at the same time.’

‘America needs Pakistan more than Pakistan needs America,’ Pakistan’s founder Mohammad Ali Jinnah insisted to American journalist Margaret Bourke-White in an interview for Life magazine just one month after the country was born.

At the time that was clearly ludicrous. And indeed, during his election campaign in 2000, George W. Bush had been asked the name of the President of Pakistan, and had no idea.

But 9/11 had changed everything. Pakistan knew the Taliban better than anyone, for it had helped create them. Afghanistan was a landlocked country most easily reachable through Pakistan with its sea ports and air connections, and the two countries shared a 1,600-mile border which split Pashtun tribes living on either side, who crossed back and forth freely.

The Americans would have found it almost impossible to mount their operation to topple the Taliban regime without Pakistan. ‘And they knew it,’ said Richard Armitage, who was Deputy Secretary of State at the time.

In his memoir, President Musharraf recounted that Colin Powell, the US Secretary of State, phoned him on the morning after 9/11 and warned: ‘You are either with us or against us.’1

The head of ISI, General Mahmood Ahmed, happened to be in Washington at the time, ironically to try to convince the CIA that the Taliban were ‘misunderstood’ and should be engaged with. On 9 September he had lunch with the Director of the CIA, George Tenet, who later wrote, ‘The guy was immovable when it came to the Taliban and al Qaeda. And bloodless too.’

The day after the attack, Mahmood was called in by Powell’s deputy Armitage. ‘It was clear he was pretty much an Islamist,’ said Armitage. ‘9/11 for Americans was a life-changing event, because we’d always been protected behind our two great oceans, unlike almost any other country in the world. Yet Mahmood started out trying to tell me, “You’ve got to understand about what our people feel.” I could see he didn’t get it.’2

Musharraf wrote in his memoir that Armitage had used the meeting to make ‘a shockingly barefaced threat’ to bomb Pakistan ‘into the Stone Age’ if Islamabad decided not to cooperate. Armitage, a big hulk of a man who admits he can be ‘fearsome’, insists he said no such thing. ‘I’d love to have been able to,’ he laughed. ‘I would have needed a cigarette afterwards. I had no such authority. But we did have very strong discussions.’

As a former soldier himself, who understood the importance of honour, he did something else. ‘I took Mahmood to my private office, the small room behind the ornate main office, and said, “I want to show you something.” I opened a box, and inside was this Star of Pakistan I’d been awarded. “You see this?” I said. “No American would accept this ever if Pakistan is found wanting in assisting us. Ever.”’

The message got through. Musharraf chose cooperation, but it was hardly enthusiastic. ‘I made a dispassionate military-style analysis of our options,’ he later wrote. ‘I war-gamed them [the US] as an adversary. The question was if we do not join them, can we confront them and withstand the onslaught. The answer was no, we could not … we could not endure a military confrontation with the US from any point of view.’

The first American official to meet with Musharraf after 9/11 was Wendy Chamberlin, the US Ambassador, who had only been in Pakistan two weeks. She’d met the President when she arrived in August, and he had told her his vision was to encourage foreign investment, and to do that he realised he needed to control domestic terrorism and the sectarian violence in Karachi. ‘He thought Pakistan was the battleground in the proxy war between the Wahhabis and the Iranians, but didn’t feel empowered or think he had the tools to really crack down,’ she said.3

When she went in to see him on the morning of 13 September, she did not mince words. ‘It was the first time anyone had said directly to him, “Are you with us or against us?” He wasn’t persuaded at first.’ ‘It’s an opportunity,’ she told him. ‘We can help you in ways which will empower you to help us against internal terrorists.’ Musharraf was unconvinced. ‘He didn’t buy it. We went over and over – I said you can expect things – lifting of sanctions, the resumption of military aid, spare parts, direct assistance, grant aid … He waffled and danced around, giving me this whole bunch of crap, and in the end I turned away and put my head down in my hands. My DCM [deputy] kept looking and asked, “Wendy, what’s wrong?” I said, “I haven’t heard what I need to tell my President, which is we support you unstintingly.” Only then did Musharraf agree.’

‘Very good,’ she replied in relief.

As she walked down the long corridor out of the palace she saw CNN reporter Tom Mintier and his crew waiting. ‘I thought, “Do I tell CNN before I tell my government?” and I thought, “Yes, I do, because then I lock Musharraf in” – I felt him waffling.’

That night Colin Powell called Musharraf and sealed the deal.

For the wily Musharraf this was his chance to transform his image on the world stage. Until then he had been seen as an international pariah, having seized power in a coup on 12 October 1999 and locked up the elected Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif in the old Attock Fort.

He told anyone who would listen that Sharif had tried to kill him ‘and hundreds of innocent Pakistanis’. Musharraf had been in Sri Lanka attending a conference and playing some of his beloved golf when Sharif had clumsily tried to sack him as his army chief. Musharraf jumped on a PIA flight back to Karachi which Sharif then refused permission to land, even though the pilot said he had only twenty minutes of fuel left. With the plane circling over the Arabian Gulf the generals stepped in, took over the TV station, airport and key buildings, and arrested Sharif.

In Musharraf’s view he had done both his country and the world a favour. ‘Today we have reached a stage where our economy has crumbled, our credibility is lost, state institutions lie demolished,’ he said in an address to the nation late that first night. He suspended the constitution and disbanded parliament, but to try to make the situation seem less coup-like, he did not take the usual title of Chief Martial Law Administrator. Instead he called himself ‘chief executive’, as if Pakistan were a business. Just like previous military rulers, he insisted: ‘The armed forces have no intention to stay in charge any longer than is absolutely necessary to pave the way for true democracy.’ In the case of his predecessor Zia-ul-Haq that meant staying eleven and a half years.

I was in the country within days of the coup, and it was clear that it was widely welcomed, people handing out sweets to celebrate. Pakistanis generally viewed their politicians as corrupt and incompetent, while the army is the only really respected national institution, despite having lost every war it has fought.

I went to see Musharraf in the white-colonnaded Army House with neat rose gardens where eleven years earlier I had interviewed Pakistan’s last military ruler General Zia, and he took a leaf out of the Tony Blair speech-book on Princess Diana. ‘I’d like to be seen as the people’s general,’ he told me.

But on the eve of the millennium the international community had little stomach for coups. Another one in Pakistan seemed a retrograde step in a country that had spent half its existence under military rule. Pakistan was expelled from the Commonwealth. Even Pakistan’s traditional friend Saudi Arabia was showing a cold shoulder; the Saudi royal family was close to the Sharifs, and would go on to provide them with homes in exile.

It wasn’t just the way that Musharraf had seized power that caused international concern. Pakistan and India had fought three wars over the disputed province of Kashmir, and five months before his coup, the then army chief Musharraf had brought the two nations to the verge of a fourth, this time nuclear. As Musharraf liked to remind people, his background was as a commando, and in May 1999 he ordered Pakistani troops into Indian Kashmir disguised as jihadis. The plan was to seize a 15,000-foot strategic height called Kargil. The ill-conceived operation prompted a fierce reaction from India, which responded with aerial bombardments. Western intelligence picked up that the Pakistani army was preparing nuclear missiles.

The Kargil operation totally undermined Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif’s efforts to make peace with India after Pakistan’s nuclear tests the previous year, and he always insisted it was launched without his knowledge. He pointed out that he had just signed the Lahore Declaration with his Indian counterpart Atal Bihari Vajpayee, a bilateral treaty to normalise relations between the two countries, and that it would make no sense to then wreck it by sending troops across the agreed Line of Control which divides Kashmir. Musharraf pooh-poohed the idea that Sharif did not know, saying, ‘Nothing could be farther from the truth.’ He claimed the Prime Minister was briefed three times.

Either way, by July Sharif was in a panic, and flew to Washington, where he begged President Clinton to intervene to broker peace with India. Clinton insisted that before there could be any ceasefire Pakistan must withdraw all its troops. Sharif agreed, to the fury of Musharraf and the army, who saw it as a humiliating climbdown. ‘We became the most sanctioned country on earth’ said Chaudhry Nisar Ali, his Interior Minister, who went with him.4 The Prime Minister’s days were almost certainly numbered from that point.

‘People forget how close we came to nuclear war,’ said David Manning, who was foreign policy adviser to Tony Blair at the time.5

9/11 changed everything, making Pakistan once again crucial, just as it had been after the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan in 1979. It seemed an astonishing replay of history, for that time Pakistan had also been under military dictatorship, that of General Zia. He too had ousted an elected Prime Minister – Zulfikar Ali Bhutto – who had appointed Zia as his army chief because he thought him unintelligent and no threat, calling him ‘my monkey general’ and pretending to jerk him on a string like a puppet-master. It was an unwise move – Zia referred to Bhutto as ‘the bastard’. A few hours after the two men attended a Fourth of July reception at the US Embassy in 1977, Zia had him arrested and seized power.

He did not stop there. Bhutto was sent to the gallows on 4 April 1979, prompting worldwide condemnation.

As a vocal defender of human rights, the US President Jimmy Carter was outraged. But Pakistan was not the only country in the region in turmoil. A seismic shift in international relations was under way as a result of Islamic revolution in neighbouring Iran, prompted by the return from exile of the Shia cleric Ayatollah Khomeini. The American-backed Shah, Reza Pahlavi, was toppled in January 1979, taking the West completely by surprise. The Shah’s demise deprived the US of vital CIA listening posts to monitor its main enemy the Soviet Union. American officials looking at the map of Central Asia realised they needed Pakistan.

Yet Pakistan’s relations with the US were plummeting to a new low. On 4 November 1979 Iranian revolutionary students stormed the US Embassy in Tehran and took hostage fifty-two American diplomats and citizens. While the Carter administration was consumed by this crisis, sending warships to the Gulf, on 20 November a mysterious group of Muslim fanatics seized the Grand Mosque in Mecca, the holiest site in the Islamic world, trapping thousands of pilgrims inside. The next day, with the mosque under siege, wild rumours spread across Pakistan that the US and Israel were behind the siege. Students belonging to the Islamic Jamaat-e-Islami society at Islamabad’s elite Quaid-e-Azam University decided to take action. Thousands of students in government buses converged on the US Embassy, pouring over the compound walls and setting the buildings aflame. One hundred and thirty-eight people were trapped inside.

The Pakistan army headquarters was only a few miles down the road, yet it was almost four hours before General Zia dispatched a helicopter. It circled once over the burning Embassy then turned back, the army command apparently convinced no one still inside could have survived, and that it was not worth risking Pakistani troops to retrieve the bodies of dead Americans. However some Americans were still trapped inside, including an injured Marine who would probably have survived if he had received help. He died, as did another American who was beaten to death with one of his own golf clubs, as well as two Pakistani employees.

One US government auditor, who was relaxing eating a hot dog by the Embassy pool when the riot started, had been taken to a student dormitory and subjected to a mock trial by students. Afterwards he said he felt his crime in their eyes was ‘simply being American’.6 Maybe somebody should have taken notice that a country with such hatred for the US was unlikely to be its loyal ally.

A month later, just after Christmas 1979, everything changed, with the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan. Once again the Carter administration was caught unawares, perhaps not surprisingly, as many in the Soviet regime were just as shocked. Carter’s hawkish National Security Adviser Zbigniew Brzezinski immediately spotted a chance. ‘The day that the Soviets officially crossed the border I wrote to President Carter, we now have the opportunity of giving to the USSR its Vietnam War,’ he later recalled.

American diplomats were still sifting through the charred remains of their Embassy when their government began shipping weapons to Islamabad, though not ones that could be traced back to them. First they sent in Soviet-made ones which they had stockpiled, then later Egyptian and Chinese mortars and AK47s.

Zia was unimpressed, and dismissed an initial offer of $400 million in aid as ‘peanuts’. Then in 1981 the Republicans returned to the White House in the form of Ronald Reagan. A fervent Cold War warrior, he upped the deal to $3.2 billion. General Zia would soon be gracing the doors of the White House and 10 Downing Street. The Soviet invasion became known as ‘Zia’s Christmas present’.

In the same way Musharraf determined to make the most of 9/11. He would get the most possible from the Americans, but he would not trust them, and he would hedge his bets.

There was, however, a major problem. Having given the Bush administration his agreement, Musharraf had to convince an army that was predisposed to take a dim view of the US, and that saw the Taliban as ‘misunderstood’. As his Ambassador in Washington, Musharraf had appointed Maleeha Lodhi, a tiny, feisty woman who had been Pakistan’s first female newspaper editor, but was also close to the military. She tried to defend the Taliban to Condoleezza Rice, Bush’s National Security Adviser, arguing that it had cracked down on opium production (in November 2000 Mullah Omar had imposed a ban on poppy cultivation which reduced production from almost 4,000 tons that year to 185 tons in 2001). ‘Yeah, Stalin also got a lot of things done,’ came Rice’s dry reply.

Musharraf himself was a secular, whisky-drinking general. When I interviewed him in Army House just after he took power, his wife Sebha and another couple were sitting on a sofa in a back room eating popcorn and watching an American movie. There was shock in Pakistan when he allowed himself to be photographed cradling his pet Pekingeses, Dot and Buddy, as dogs are regarded by many Muslims as unclean.

Pakistan’s President had little personal sympathy for the Taliban; indeed, he found them exasperating at times, such as when they blew up the ancient Bamiyan Buddhas in March 2001 after refusing to bend to international pressure, including a mission by his own Interior Minister, General Haider, and ISI chief General Mahmood.

However, Musharraf had personally fought in two of Pakistan’s wars against India, and was obsessed by trying to capture Kashmir, the former princely state which had been left divided in 1947 when India was given independence from Britain, and Pakistan was created. Thus he understood the value of a proxy force, one of Pakistan’s main weapons being the militants it trained to infiltrate Kashmir, and he often differentiated between terrorism and jihad.

Other senior generals went much further. When Zia became army chief in 1977 he had introduced a programme of Islamisation. I interviewed him in 1988, just a few weeks before the mysterious plane crash in which he was killed, and asked him why it had been necessary to try to ‘Islamise’ a country where the overwhelming majority of the population were Muslim. ‘It’s what the people want,’ he said. ‘Education, agriculture, industrialisation – there are 101 important issues, but the fundamental issue is that this country must have the spirit of Islam.’7

Nowhere had he ensured this more than in the army. From the beginning, Pakistan’s military leaders had seen themselves as defenders of their religion and had used Islam as a rallying cry. During the 1971 civil war which culminated in the loss of Bangladesh, Pakistan’s then ruler General Yahya Khan motivated his soldiers by declaring the Mukti Bahini (the Bengali guerrillas) to be a kafir army against which the Pakistani army was waging a legitimate jihad. His army chief, General A.A.K. ‘Tiger’ Niazi, told reporters in Dhaka, ‘Remember, every Muslim soldier is worth ten Hindus.’ Ten days later the General was forced to surrender on Dhaka racecourse in front of crowds shouting anti-Pakistan slogans. The humiliating defeat had a major impact on Pakistan’s soldiers, many of whom felt that they had lost because they were not good Muslims, and Islam began to play a greater part in military training. Musharraf, who was a commando at the time, though not involved, said he ‘literally wept’.8

Under Zia, for the first time piety became a part of an officer’s evaluation. The role of the army became not just to protect the country’s geographical borders, but also its ideology as the first nation created in the name of Islam, and a particular kind of Islam. Zia changed the battle cry of the Pakistan army commandos from the Shia ‘Nara e Haidry – Ya Ali’ to the Sunni ‘Allah Hoo Allah Hoo!’ and built mosques in each garrison, appointing imams for every regiment. These were generally from the ultra-conservative Deobandi group Tableeghi Jamaat (TJ), and he encouraged soldiers and officers to spend their leave participating in its preaching missions. He was the first chief of staff to attend the huge annual gathering of TJ at Raiwind, near Lahore.

From the start Zia cultivated a close relationship with Pakistan’s largest religious party, Jamaat-e-Islami, which had considerable street power. He met the JI chief for ninety minutes the night before the hanging of Bhutto, and JI members took to the streets to celebrate Bhutto’s death.

During Zia’s tenure as army chief, the writings of JI’s founder Maulana Maudoodi, including his book Jihad in Islam, started to circulate in army-run educational institutions. Many officers began to openly express their support for JI’s ideology. In the mosques it was as if jihad became the sixth pillar of Islam, along with the belief in one god; the namaz or prayers five times a day; giving alms or zakat; roza, fasting from dawn till sunset during the month of Ramadan; and haj, the pilgrimage to Mecca which every able-bodied Muslim was supposed to do once in their lifetime. This was encouraged by the CIA as a recruiting tool for defeating the communists in Afghanistan. Ziauddin Yousafzai, whose daughter Malala would later be shot by the Taliban, was growing up in a poor, remote village in Swat in the 1980s, during Zia’s rule. He said talk of jihad was so glorified that many of his friends went across the border to fight, and he almost went too.

There were other influences at work. Several army officers posted to the Arab states around the Persian Gulf in the 1970s and 1980s came back heavily influenced by an orthodox interpretation of Islam. Zia promoted those who thought like him, and they invariably rose to occupy prominent positions in the military hierarchy. Many more officers came under religious influence as they worked directly with the Afghan mujaheddin, seeing their defeat of the Russians as a victory of Islam against an infidel superpower. It was not just a policy, but a cause they believed in.

This was reinforced when relations were cut off in 1990 and Pakistani officers had no more access to US military academies.

By 2001 those who had come through Zia’s indoctrination were in senior positions. Some of the key generals who had brought Musharraf to power while his plane was circling the skies above Karachi were committed Islamists. One to whom Musharraf was particularly beholden was General Mahmood, who had been his front-line commander in the Kargil raid. At the time of the coup Mahmood was commanding 10th Corps, the key unit stationed in Rawalpindi which moved into Islamabad to detain Nawaz Sharif and secure government buildings.

The most important people for Musharraf to win over were the nine army corps commanders, the real power in the land, each controlling as many as 60,000 men. He summoned them from all over the country for a long and heated meeting in the operations room of the Pakistani Joint Chiefs of Staff. Like General Mahmood, whom he had appointed ISI chief, some were very close to the Islamic militants they had nurtured for years, and could not believe that Musharraf would ally with the unreliable US against them. As Bob Woodward wrote in Bush at War: ‘In so many words, Powell and Armitage [were] asking Pakistan to help destroy what its intelligence service had helped create and maintain: The Taliban.’

The army which used to send many of its officers to train in the US had become virulently anti-American, furious at how Washington had cut off support once the Russians had been ousted from Afghanistan. Many of them believed the US was behind the mysterious plane crash that killed Zia in 1988 along with many senior officers.

Musharraf told his generals that Pakistan had no choice but to cooperate with the US or be declared a terrorist state, and thus also attacked. He argued that if he refused to cooperate, then the great enemy India would step in and offer its bases to the US, and Pakistan’s very existence could be threatened. The US would destroy Pakistan’s military forces and take the opportunity to destroy its nuclear weapons. The Taliban were ‘not worth committing suicide over’, he said. He cited the example of them blowing up the Buddhas to point out that ‘After they came to power we lost much of the leverage we had over them.’

As always in Pakistan, even the Buddha story had two versions. According to Mullah Zaeef, the Taliban Ambassador who accompanied the Pakistan delegation, General Haider warned Mullah Omar about the risks of continuing to shelter bin Laden. ‘I am up to 80 per cent certain that the Americans will attack you,’ he said. As Haider talked, Zaeef said, ‘Mahmood leaned towards me and whispered, “What is this silly donkey talking about?”’9

Three days after 9/11, Musharraf telephoned Colin Powell, agreeing to accept his list of seven demands. These included allowing overflights, cutting all arms and fuel shipments to the Taliban and al Qaeda, and publicly condemning the terrorist acts. Less publicly, he allowed American forces to use four airbases in Baluchistan and Sindh, supposedly just for logistics. It later emerged from US Central Command that over 50,000 combat missions were flown out of these.

However, Musharraf made it clear that he had agreed to the US demands against public sentiment, and would need to show Pakistan was getting some benefit in return. For a start, he wanted the removal of all the sanctions imposed because of the country’s nuclear programme and the coup. He also wanted the cancellation of its $3 billion debt to the US, and some F16s for his generals.

Ambassador Wendy Chamberlin went in to see him again on 15 September to seal the details. ‘Everything he promised that day he did deliver,’ she said. ‘He didn’t get everything he wanted, but nor did we. He wanted us to support their position on Kashmir – I said no. He wanted to make sure the Indian air force didn’t overfly Pakistan, which we agreed, and absolutely no US combat troops in Pakistan. He did agree the use of airbases as well as over-flight rights. He also said, “We will help take down al Qaeda and the Taliban, but if there are any Pakistani citizens involved, you can’t arrest them, we’ll do that.” It was one of the red lines.’

Within ten days of Musharraf’s agreement, and just twelve days after 9/11, Bush had waived all sanctions against Pakistan and asked Congress to reschedule old loans and agree fresh loans of more than $600 million. Japan and the EU followed suit. Over the next few years Musharraf would get billions of dollars. The man whose name Bush had forgotten would end up being known as Bush’s best friend.

But the lack of trust was still there on both sides. ‘With Pakistan you get part of the story, never the whole story,’ said Armitage. ‘There are those who would say: “How do you know when Pakistanis are lying? Their lips are moving.”’

The first indication that Musharraf might not be entirely on-side came just eight days after 9/11 with his public address to the nation. By then I was in Pakistan, and I watched eagerly to see what he would say. He made clear the pressure he was under. ‘Pakistan is facing a very critical time,’ he said. ‘If we make any mistake they can culminate in very bad ends.’ Yet he did not condemn the Taliban or al Qaeda, or blame them for 9/11, as he had agreed with Powell. ‘He wanted to break with the Taliban,’ says Armitage. ‘But at that point we didn’t want him to, as they were holding two American women [among eight foreign missionaries arrested in August] and thought Pakistan could help.’

Others say Musharraf already thought he could play a double game, and fool the Americans just as Zia and ISI had in the 1980s. ‘The ISI had become a mini CIA with Afghanistan,’10 said Husain Haqqani, who was very familiar with the agency, having worked with them in 1988 to try to stop Benazir Bhutto coming to power, then ending up working for her, eventually becoming Pakistan’s Ambassador in Washington from 2008 to 2011.

Bob Grenier, who was CIA station chief in Islamabad at the time of 9/11, was not surprised. ‘Right from the start, I was convinced that the Pakistanis did not want to foreclose their options. They’d seen the Americans come and go in the past. They weren’t at all sure they trusted Hamid Karzai. And irrespective of how they felt about him, I think there was probably a tendency to see him as a Pashtun face of what was really a Northern Alliance government. They were very distrustful, obviously, of the Northern Alliance.’11

Such was the lack of trust that while the US agreed no military action would start until General Mahmood’s mission to see Mullah Omar in Kandahar, the CIA sent their own mission, led by Grenier, to meet one of Mullah Omar’s representatives in Quetta. It had no more success.

The Taliban leadership was outraged at Musharraf’s volte-face, but not surprised. Mullah Abdul Salam Zaeef was Ambassador to Pakistan at the time of 9/11, and became known as ‘the Smiling Taliban’ for his jovial 4 o’clock press briefings in his garden during the US bombing campaign. He said no Afghans really trusted ISI: ‘The wolf and sheep may drink water from the same stream, but since the start of the jihad the ISI extended its roots deep into Afghanistan like a cancer. Every ruler complained about it, but none could get rid of it.’

Before the bombing campaign started three top ISI officers came to Saeef’s house in Islamabad to pledge their support – General Mahmood, his deputy General Jailani, and Brigadier Farooq who ran the agency’s Afghan desk. ‘We want to assure you that you will not be alone in this jihad against America,’ they told him. ‘We will be with you.’ Saeef was enraged. ‘You speak of jihad while the Americans are stationed in your airbases and flying through your airspace, even attacking Afghanistan based on your intelligence reports!’ he shouted. ‘You should be ashamed to even utter the word jihad!’ When he looked at General Mahmood, ‘tears were running down his face’. As for Jailani, ‘He was crying out loud with his arms around my neck like a woman.’

Shortly afterwards, all three were removed from their posts in what was described officially as ‘normal military procedures’. General Mahmood was retired and replaced by General Ehsan ul Haq, whose instructions were to ‘weed out the beards’. Brigadier Faruq and General Jailani were both transferred. Mahmood has never spoken about these events, but his friends told me he felt totally betrayed. Once I managed to speak to his wife by phone, and asked what her husband thought of Musharraf. ‘How do you think he feels?’ she replied angrily.

Mullah Zaeef said he was told that before they left their posts these ISI officers had burned documents regarding Afghanistan which the Americans had requested, and had advised Mullah Omar to find safe haven.

General Zia’s son Ijaz-ul-Haq, who was in close contact with senior military and Taliban because of the respect in which they held his late father, predicted the changes at the top would make little difference. ‘ISI chiefs only last one or two years anyway,’ he told me. ‘The real people running the game are the majors and colonels lower down, and they haven’t switched sides. It isn’t a matter of policy for them; it’s a matter of belief.’

The Interior Minister General Haider agreed. ‘It cannot be ruled out that some members of the intelligence services may have their sympathies with the other side. You see, since 1979 we had been actively helping and directing the Taliban along with the Americans against the Soviets. When suddenly a U-turn is taken, your [individual] contacts will remain.’12

The biggest indication of how deeply ISI were still involved came after General Mahmood had been transferred, in an episode that became known as ‘the Airlift of Evil’. By mid-November 2001, the US bombing had forced the Taliban and al Qaeda out of Kabul and concentrated their fighters in two main areas – Kandahar in the south and Kunduz in the north. In Kunduz, al Qaeda fighters, along with thousands of Taliban under the command of Mullah Dadullah, had been surrounded by Northern Alliance forces from two rival commanders – Atta and his Tajik forces to the south, and Dostum and his Uzbeks to the west. But they were refusing to surrender to these commanders, who they feared would slaughter them. Instead they sent radio messages offering to surrender to the US or the UN.

There was one other problem. Trapped with them were hundreds of ISI and Frontier Corps officers who had been sent from Pakistan to help. Musharraf phoned Bush and asked for a pause in the US bombing so that the Pakistani air force could rescue them. On 15 November Northern Alliance commanders told journalists that Pakistani planes had landed at Kunduz. This was strongly denied by Donald Rumsfeld and the Pentagon, and the foreign media were distracted by reporting the fall of Kabul. In fact, for each of the next few nights there were night-time rescues, and they were flying out not just ISI but also Taliban and al Qaeda.

When Kunduz finally fell to the Northern Alliance on 24 November, so many had been flown out that only 3,300 Taliban remained, about half what the CIA had estimated. Those men had been right to be worried about what would befall them. Most of them ended up packed into shipping containers, where they suffocated.

The Northern Alliance leadership was furious that once again the Americans had allowed Pakistan to say one thing and do something else. ‘I don’t know how much we understood of what we were getting into,’ said Armitage. ‘And attention was already moving elsewhere.’

The reality was that Washington’s attention had shifted elsewhere. ‘We rapidly moved on to Iraq,’ said Richard Armitage. ‘Frankly, we didn’t care much about Afghanistan. We didn’t have a strategy for Afghanistan. Rumsfeld wanted to pull out of there early on. We would have been perfectly willing to let the Taliban sit it out if they’d stopped helping the Arabs.’