Читать книгу Farewell Kabul: From Afghanistan To A More Dangerous World - Christina Lamb - Страница 8

The Leaving

ОглавлениеCamp Bastion, Helmand, 26–27 October 2014

‘Ladies and gentlemen, please take your seats for the End of Operations Ceremony!’ The American voice boomed enthusiastically over the speakers as if it were the drum roll for a sporting event.

Rows of grey fold-up chairs had been arranged facing a large blast wall painted with murals marking each of the last few commands in Helmand. In front of the wall two detachments of US Marines and British troops stood to attention, flanked on either side by Afghan soldiers, who had been instructed beforehand not to hold hands. Above flew four flags – the Union Jack, the Stars and Stripes, and those of NATO and Afghanistan.

A padre read some Koranic verses, then three American generals took turns at the plinth to speak. One of them was the last commander in Helmand, Brigadier General D.D. Yoo of the US Marines, a man of Napoleonic stature both in height and personality who took the mike from the lectern to strut in front of the audience as if about to burst into song.

Phrases from the speakers, each as determinedly upbeat as the announcer, swam in the hot air like speech bubbles. No one spoke of defeat, or retreat, or withdrawal in the face of an intransigent enemy, or of publics and politicians back home who could take no more flag-draped coffins.

‘This transfer is a sign of progress,’ said Brigadier General Yoo. ‘It is not about the coalition. It is really about the Afghans and what they have achieved over the last thirteen years.’

Helmand would now be under control of Afghan forces, commanded by Major General Sayed Malouk. ‘We are ready,’ Malouk insisted, even though he didn’t quite look me in the eye as he said it. He had already lost almost eight hundred men that fighting season, and had himself narrowly escaped a roadside bomb in Sangin.

No British officer spoke, and Britain’s eight-year role in Helmand garnered barely a mention, which seemed odd, for this had been the country’s longest war in modern times, and its hardest fighting for more than half a century.

The hot sun beat down and guests swigged from bottles of mineral water as ‘God Save the Queen’ and ‘The Star-Spangled Banner’ were played and the flags were lowered. The Union Jack was carefully folded, and handed to Brigadier Rob Thomson, the last British commander. Only the Afghan flag was left fluttering as Camp Bastion came under Afghan command, and Britain’s fourth war in Afghanistan officially came to an end.

Guests were taken into a cabin where a banquet lunch of smoked salmon, slow-cooked beef and chocolate fudge cake had been specially flown in. The genial Afghan army chief General Sher Mohammad Karimi presented Brigadier General Yoo with a commemorative certificate and a carpet, and both sides took souvenir photographs. It all seemed surreal.

I felt tears stinging my face. Four hundred and fifty-three British soldiers had been lost in Afghanistan, of whom 404 died in Helmand, many of them young enough to be my son. Hundreds more had lost limbs to roadside bombs or been mentally scarred for life. Tens of thousands of Afghans had lost relatives or homes, and I had met many Helmandis living as refugees in a camp in Kabul, begging for scraps of dry bread and meat fat, and burying children in the mornings who had frozen to death overnight in the winter cold.

Watching the flag come down felt like the end of everything. This fierce, turtle-shaped country had been part of my entire adult life, longer than any relationship or job. It was twenty-seven years since I’d first come to Afghanistan as a young wannabe foreign correspondent, crossing the Hindu Kush with the mujaheddin fighting the Russians, and falling unequivocally in love with this land of pomegranates and war. I’d had narrow escapes in muddy fields nearby, both with those mujaheddin who went on to become Taliban, and then with British soldiers fighting those Taliban. My first big assignment was covering the Soviet withdrawal in 1989, and never in my wildest dreams had I imagined I would be back a quarter of a century later, covering my own country’s ignominious departure. Just as after the Russians had gone, everyone had lost interest in Afghanistan, now Western troops were leaving I wondered if anyone would care.

The Union Jack at Bastion was the last to come down over Helmand. Once there had been 137 British bases across the province, but over the last year these had all been bulldozed one by one and turned back to desert, home again only to scorpions and camel spiders.

Some, in places like Sangin, Musa Qala and Naw Zad, had become unlikely household names back in Britain. Many were small, primitive FOBs – Forward Operating Bases: like Camp Inkerman, which was known to everyone as Camp Incoming because it was so frequently hit. Conditions in these places were described as ‘austere’, which meant showers were hot bags once a week, the dust so deep that you felt it sucking at your boots, and the toilet a stinking pit that was targeted so often it was known as Tali-alley.

Bastion was where it had all started. When it opened in 2006 it was a gritty, grey, sprawling place on the edge of the Dasht-e-Margo, or Desert of Death, that had previously been used for camel-grazing, according to the agreement signed by the Defence Secretary John Reid. Over the years, like the war, it had been expanded and expanded to become Britain’s biggest overseas camp since World War II, the first billion-pound base. At its height it housed more than 30,000 people with a coffee bar, Pizza Hut, Kentucky Fried Chicken, three gyms, state-of-the-art hospital and even a water-bottling plant producing 15,000 gallons of Bastion Water a day. The camp’s three canteens had served a hundred million meals since 2006, getting through 66,500 eggs a week and 6,000 tubs of ice cream, all flown in. Its airfield saw so many flights a day – six or seven hundred, from jumbo jets to unmanned Reapers – that it had become Britain’s third busiest airport.

Now everything had been packed up, bar-coded and sent back or destroyed. The detritus of twenty-first-century war is so vast that after more than eight years in Helmand, Lieutenant Colonel Laurence Quinn, the engineer who oversaw both its building and its dismantling, compared it to packing up ‘a town the size of Aldershot with Gatwick airport bolted on’. Five thousand five hundred shipping containers had gone back, mostly by air. The hospital, the pie shop in Lashkar Gah, the air-conditioning units, the Naafi shop, the water-bottling plant had all gone, as had the tented camps, one of them ending up sheltering refugees in a new war in Iraq. The naughty posters had been stripped down and the rockery dismantled. Thousands of unspent bullets were fed into a popcorn machine to be harmlessly exploded. Fifty aircraft had been sent back, and 3,300 armoured vehicles, including Mastiffs and Wolfhounds, six-wheeled armour-caged monsters costing more than £1 million apiece, so different from the open Snatch Land Rovers in which troops had started out and that the Americans mocked as ‘safari vehicles’. The security cameras and radios were stripped from the control towers, leaving the Afghans who would man them no way to keep watch on the perimeter or to communicate. Hardest of all to pack was the massive Giraffe rocket-detector. Last to go was the airport radar and a foam-dispensing fire engine. The Afghans joked sourly that the British would have taken the concrete walls if they could.

As if the foreigners were trying to erase all signs of their presence, the murals had been painted over. One of the most moving sights at Bastion had been the Memorial Wall to the fallen, with 453 brass plates bearing the names of all those killed, under the lines from the First World War poet John Maxwell Edmonds: ‘When you go home tell them of us and say/for your tomorrow we gave our today.’ Even that had been dismantled, and there would be no monument in Helmand to British lives lost. There would be no voices calling ‘We are the dead,’ for the poppy fields of Helmand would be very different from those of Flanders a century earlier.

On the last night, even the electricity was switched off, a young British corporal, Sam Boswell, nervously turning off the final switch at 3.30 a.m. on Monday, 27 October. ‘I double-checked and it was definitely off,’ he told me afterwards. It was eerie driving around the camp in its final hours of British presence. Under the faint glimmer of a crescent moon reclining low in the sky, abandoned patches of desert stretched for miles and miles, ringed by fences of barbed wire. The only buildings left were the control tower, some giant hangars that had housed workshops or aircraft, and the line of towers around the twenty-three-mile perimeter. Adding to the apocalyptic air, a few bonfires were burning to incinerate the last remaining sensitive documents.

But the strangest thing was not the emptiness. The Bastion I knew had always hummed with the sound of large generators blasting air into each of the tented camps, and the constant take-off and landing of planes. Now there was silence. For that last night the remaining thousand or so British and American troops withdrew into a small camp by the side of the airfield. The outer perimeter towers were guarded till the end, and ‘lumes’, or illumination mortars, were fired off in a final expensive fireworks display meant to present a show of strength to the Taliban.

In the countdown to what was called ‘H Hour’, the withdrawal was coordinated from a control room facing the runway. British and American soldiers sat at a T-shaped table mounted with framed photographs of the Queen and the action-movie star Chuck Norris, and tapped away at tablets or spoke on radios. In front of them a giant screen played a feed from a Reaper somewhere overhead. The footage showed a compound just south of Bastion, where two men were clearly visible walking around outside. As we watched, the men fired off a rocket-propelled grenade. I was quickly shuffled out while the soldiers discussed whether to respond. In the end they did nothing.

For the final six hours before the withdrawal the air above us was full of Apaches, Cobras, Tornadoes and B1 bombers circling around. Nothing was left to chance. ‘We don’t want anything that looks like helicopters fleeing from the US Embassy roof in Saigon,’ had been the instructions from Whitehall to RAF officers orchestrating the event.

The Afghan forces that the British and Americans had been talking up so highly were not being trusted to guard their exit – even the perimeter guard towers were only handed over at the last minute. The air-traffic controllers destroyed equipment in the control tower before leaving. The final wave of aircraft was guided out by an airborne control team on a Hercules.

In the end the departure was so perfectly choreographed one could almost forget it was a retreat. Fifteen waves of Hercules transport planes and a last one of choppers – four monstrous CH53s, two Hueys and two British Chinooks. It was the biggest airborne withdrawal since the Berlin Airlift. I went on one of the last waves to Kandahar, landing in time to watch the final helicopters swooping in and disgorging the troops, so cinematic that the only thing missing was a soundtrack.

The airlift went so smoothly it finished more than three hours ahead of schedule, at 11.54 a.m. on Monday, 27 October. Yet even before the soldiers had set foot back on home soil, recriminations started. There were calls for a Chilcot inquiry like that into the war in Iraq, and the country looked set for the same kind of long and bitter blame game as that which followed America’s involvement in Vietnam. Lord Paddy Ashdown, the former leader of the Liberal Democrats, called it ‘catastrophic’. Admiral Lord West, the former First Sea Lord, described the war as an ‘abject failure’, and demanded a public inquiry. Lieutenant Colonel Richard Williams, a former commander of the SAS, wrote an article in The Times which lambasted the lack of planning, adding, ‘It is also clear to me that we did not run or command it well either.’

There would be no victory parades, for there had been no victory. Lofty aims of transforming the country were forgotten. Now it was about damage control. ‘Helmand is not the Western Front; it doesn’t end in a hall of mirrors in Versailles like 1918,’ said Brigadier Rob Thomson. ‘I don’t think wars today end in defeat or victory; you set the conditions to allow other elements to come in.’

The question on everyone’s lips was how long would it be till the Taliban raised their black flags instead? Already they were back in many districts, showing their presence, if not yet hoisting flags.

Brigadier Thomson would not be drawn on the future. ‘There’s clearly going to be a contest,’ he said, ‘and it would be foolish of me to make a prediction into the long term about how this will run.’ The Taliban, meanwhile, had already declared victory. ‘The flight of the British invaders is another proud event in the history of Afghanistan,’ said their spokesman.

Locals watched and shrugged at the latest foreigners to come and leave their country. They had been surprised when the Angrez, as they called the British, came back, for the British Army had suffered one of the worst defeats in its history at nearby Maiwand in 1880. No one had ever really explained why they had returned, if not to avenge that. Nor had they understood what the point of killing Taliban was, when more just came over the border from Pakistan, a country which had received more than $20 billion in Western aid since 9/11, and turned out to have been hosting bin Laden.

So the farmers just got on and harvested their poppy, for it would be a record crop of more than 200,000 hectares, almost half of that in Helmand, by far the world’s biggest producer. Most villages still had no jobs, no electricity, no services.

Ministry of Defence bureaucrats could spend money commissioning slick ‘legacy videos’, but the truth was that Britain’s fourth war in Afghanistan had ended in ignominious departure. It had been the country’s longest war since the Hundred Years War, longer than the Napoleonic Wars, and the most deadly since the Korean.

British officers might be lobbing accusations at each other, but Helmand was a reflection of the whole war in Afghanistan. In the thirteen years since invading Afghanistan in response to 9/11, NATO forces had lost 3,484 troops and spent perhaps $1 trillion. For the Americans, who lost the most soldiers and footed most of the bill, it was their longest ever war. What had once been the right thing to do – what President Barack Obama called ‘the good war’ – had become something everyone wanted to wash their hands of.

How on earth had the might of NATO, forty-eight countries with satellites in the skies, 140,000 troops dropping missiles the price of a Porsche, not managed to defeat a group of ragtag religious students and farmers led by a one-eyed mullah his own colleagues described as ‘dumb in the mouth’? And why had they even tried?

Overall, more than $3 trillion had been spent in Iraq and Afghanistan in response to a terrorist attack that cost only between $400,000 and $500,000 to mount.1 The aim, as stated by Gordon Brown while he was Prime Minister, was that ‘We fought them over there to not fight them here.’ Yet it was hard to see how these wars had left the West safer. On the contrary, we had ended up with the Pakistani Taliban, who were far more dangerous than the original Afghan Taliban, and regional offshoots of al Qaeda like al Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP) in Yemen, al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM) in North Africa, al Shabaab in Somalia and Boko Haram in Nigeria. Mullah Omar was still at large, as was Ayman al Zawahiri, Osama bin Laden’s deputy, who had succeeded him as leader. Some of the original al Qaeda from Afghanistan/Pakistan that was supposed to have been incapacitated had turned up under the name Khorasan in Syria. Lastly, there was ISIS, the so-called Islamic State of Iraq and Syria, far larger and more terrifying than al Qaeda, which by the end of 2014 controlled territory the size of Britain in Iraq and Syria, as well as making inroads in Libya. ISIS had declared a Caliphate, and was vowing to extend its reign of terror and beheadings as far as Spain, prompting the US and Britain to send advisers back to Iraq, and sucking them back into their fourth war since 9/11. So many Europeans had been attracted as jihadists into its ranks that intelligence chiefs were warning an attack on British soil was ‘almost inevitable’.

From Libya to Ukraine, around the world conflicts were springing up everywhere, like the Whack-a-Mole arcade game in which no matter how many moles are smashed with a hammer, more simply pop up elsewhere. There were more countries undergoing wars or active insurgencies than at any time since the Second World War, yet never had the major powers been wearier of intervention. What had started with hopes of a new world for Afghan women had ended with medieval black-hooded executioners, religious wars across the Middle East, and Jordan’s King Abdullah warning that World War III was at hand.2

As for Afghanistan, schools, clinics and roads had been built across the country, yet it remained one of the poorest places on earth. By the end of 2014 the US would have spent more on Afghanistan than it had on the Marshall Plan to rebuild Europe after the Second World War. Yet poverty remained stubbornly high, with more than a third of Afghans still surviving on less than 80p a day, according to the United Nations Development Programme, and half its children having never set foot in a classroom.3 In a land where 70 per cent of the population was under thirty, the majority had only ever known war. War against the Russians, war against each other, war between the West and al Qaeda and the Taliban. In this last, 15,000 Afghan troops had died, as well as more than 22,000 civilians, and the numbers were going up each year.

The West’s relations with the country it had been trying to help, and the ruler it had installed, had deteriorated to such an extent that in President Hamid Karzai’s farewell speech to his cabinet in late September 2014, there were no thanks for Britain or America. Instead he blamed America – as well as Pakistan – for not wanting peace. ‘We are losing our lives in a war of foreigners,’ he raged.

No one who goes to war comes back unchanged. I spent two wars in Afghanistan – the first as a recent graduate (covering the final showdown of the Cold War), the second as a new mum in the aftermath of 9/11 (covering a war involving my own country). I left a middle-aged woman who had more than used up her nine lives, with a teenage son going into a world far more ominous than that in which I grew up.

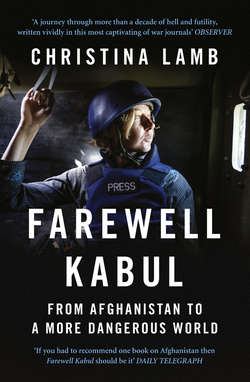

This book sets out to tell the story, by someone who lived through it, of how we turned success into defeat. It is the story of well-intentioned men and women going into a place they did not understand at all – even though, in the case of the British, there was plenty of past history. The 1915 ‘Field Notes on Afghanistan’ given to those heading out to the Third Anglo–Afghan War are full of salutary warnings, starting right off with ‘Afghans are treacherous and generally inclined towards double dealing.’ Major General Dickie Davis, sent to Afghanistan in 2002, recalls how when he was briefed on the mission at military headquarters (PJHQ) before departing, he asked, ‘How many hundreds of years have we got?’4

Anyone visiting the NATO military headquarters in Kabul might be struck by the number of saplings planted on the small green over the years – one for each commander. There had been seventeen in the course of the war. In Helmand alone Britain had had seventeen commanders, each there for just six months. They might wonder too how a war could be fought effectively when there was no real border with the neighbouring country of Pakistan, which the enemy made its safe haven.

Yet more than a military failure, this was a political failure. Just as a lack of imagination had failed to predict the possibility of using passenger aeroplanes as weapons, a lack of imagination caused us to assume people wanted the same as us, and that because our enemy were uneducated they were ignorant savages we could easily outsmart. It was a strategy that ignored tribal realities and other people’s national interests, including those of our key partner. Along the way, the West lost the moral high ground by giving positions of power to those the Afghan people most blamed for the war, and by the detention and torture of prisoners, some of whom had simply been in the wrong place at the wrong time.

Over those thirteen years I watched with growing incredulity as we fought a war with our hands tied, committed too little too late, became distracted by a new war of our own making based on wrong information, and turned a blind eye as our enemy was being helped by our own ally. Yet only when Osama bin Laden was found living in a house in a Pakistani city, not far from the capital, did it seem to dawn on people that we may have been fighting the wrong war.

Throughout this period I lived in Pakistan, Afghanistan, London and Washington, as well as covering the other war and its aftermath in Iraq, and visiting Saudi Arabia, which was the birthplace of fifteen of the nineteen 9/11 hijackers. I spoke to almost all key decision-makers, including heads of state and generals, as well as embedding with American soldiers and British squaddies actually fighting the wars. Most of all I talked to people on the ground. I travelled the length and breadth of Pakistan, from the tribal areas to the mountain valleys of Swat, from the cities of Quetta, Lahore and Karachi to the jihadist recruiting grounds in madrassas and in remote villages of the Punjab. In Afghanistan my travels took me far beyond Helmand – from the caves of Tora Bora in the south to the mountainous badlands of Kunar in the east; from Herat, city of poets and minarets in the west, to the very poorest province of Samangan in the north, full of abandoned ghost villages. I also travelled to Guantánamo, met Taliban in Quetta and from the Quetta shura, visited jihadi camps in Pakistan, and saw bin Laden’s house just after he was killed. Saddest of all, I met women whom we had made into role models and who had then been shot, raped, or forced to flee the country.

On the way I had several narrow escapes – from being ambushed by Taliban with the first British combat troops in Helmand to travelling on Benazir Bhutto’s bus when it was blown up in Pakistan’s biggest ever suicide bomb. I lost many friends in those years, a number of whom appear in the following pages.

I could not have lived through all this and just walked away. I have written this book because I thought it was a story that needed telling. How it ends is yet to be told.