Читать книгу The Man Who Created the Middle East: A Story of Empire, Conflict and the Sykes-Picot Agreement - Christopher Sykes Simon - Страница 6

Introduction

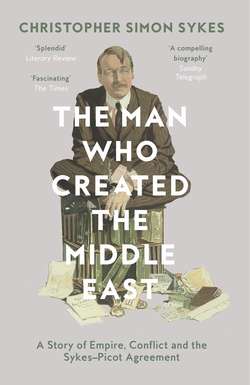

ОглавлениеIt is extraordinary to think that my grandfather, Sir Mark Sykes, was only thirty-six years old when he found himself signatory to one of the most controversial treaties of the twentieth century, the Sykes–Picot Agreement. This was the secret pact arranged between the Allies in the First World War, in 1916, to divide up the Ottoman Empire in the event of their victory. It was a piece of typical diplomacy in which each side tried its best not to tell the other exactly what it was that it wanted, while making the vaguest promises to various Arab tribes that they would have their own kingdom in return for fighting on the Allied side. None of these promises materialised in the aftermath of the War, Arab aspirations being dashed during the subsequent Peace Conference in which the rivalries and clashes of the great powers, all eager to make the best deals for themselves in the aftermath of victory, dominated the proceedings, and pushed the issue of the rights of small nations into the background. This was the cause of bad blood, which has survived to the present day.

Perhaps it is because my grandfather’s name is placed before that of his fellow signatory that history has tended to make him the villain of the piece rather than Monsieur Georges-Picot. ‘You’re writing about that arsehole?’ commented an Italian historian in Rome last year, while even my publisher suggested that a good title for the book might be ‘The Man Who Fucked Up the Middle East’. These kinds of comment only strengthened my resolve to find out the truth about a man of whom I had no romantic perceptions, since he died nearly thirty years before I was born. I felt this meant I could be objective.

I also knew that there was much more to him than his involvement in the division of the Ottoman Empire, which occupied only the last four years of his life. Before that he had led a life filled with adventures and experiences. As a boy he had travelled to Egypt and India, explored the Arabian desert and visited Mexico. He had been to school in Monte Carlo, where he had befriended the croupiers in the Casino, before attending Cambridge under the tutorship of M. R. James. His first book, an account of his travels through Turkey, was published when he was twenty, before he went off to fight in the Boer War. He travelled extensively throughout the Ottoman Empire, mapping areas that cartographers had never before visited. He was generally recognised as a talented cartoonist, whose drawings appeared regularly in Vanity Fair, as well as being an excellent mimic and amateur actor, gifts that, when he eventually entered the House of Commons, ensured a full house whenever he spoke. All this against a background of a difficult and lonely childhood that he rose above to make a happy marriage and become the father of six children.

I decided to tell his story largely through his correspondence with his wife, Edith, a collection of 463 letters written from the time they met till a year before his death. As well as chronicling his daily activities, they provide a fascinating insight into his emotional state, since he never held back from expressing his innermost feelings, pouring his emotions onto the page, whether anger embodied in huge capital letters and exclamation marks, humour represented by a charming cartoon, or occasionally despair characterised by long monologues of self-pity. They are also filled with expressions of deep love for Edith, with whom he shared profound spiritual beliefs. Sadly, almost none of her letters have survived.

Needless to say his writings also often embody the attitudes regarding race that were common among members of his class in a world which was largely ruled by Great Britain. Though they are anathema to us today it was considered quite normal in the nineteenth century to refer to Jews as ‘Semites’, the peoples of the East as ‘Orientals’, and the South African blacks as ‘Kaffirs’. With this in mind I decided not to sanitise these terms when I came across them. I was also mindful of the fact that while Mark expressed many racist views about the Jews when he was a young man, he radically changed his mind after meeting the celebrated journalist Nahum Sokolow and embraced Zionism.

When I was growing up my father rarely talked about my grandfather, and when he did so he always referred to him as ‘Sir Mark’. I think growing up in his shadow had been too much for him. Certainly his former governess, Fanny Ludovici, known in the family as ‘Mouselle’, who worked as his secretary, endlessly regaled us with stories of what a wonderful man our grandfather had been and what a loss it was to the world that he had died so young. My aunts and uncles also expressed this view, though when I actually interviewed my Aunt Freya, Mark’s firstborn, about her father for a book I was writing, The Big House, she had very little to say about him, and I suddenly realised that the reason for this was that she scarcely knew him as he was hardly ever at home. My interest was aroused, however, and when the Arab Spring sparked off a series of revolutions that spiralled into the situation we see today, with the Middle East seemingly on the point of disintegration, and the words Sykes–Picot regularly on the front pages, the time seemed right to tell the story of the 35-year-old junior official who was one of the men behind it.