Читать книгу Gardens in the Modern Landscape - Christopher Tunnard - Страница 12

ОглавлениеFOREWORD

IT is now ten years since the material in these pages first appeared in The Architectural Review. Very little creative work has been done during the interval owing to the war. The author, like everyone else, has been engaged in other occupations, with little time for reflection on the charm of natural things; but since it is his publisher’s and his own opinion that the book should reappear very much in its original form, a few remarks on conclusions reached during this relatively inactive period may not come amiss.

The opinion expressed in the book that the eighteenth-century invention of landscape gardening was among the most notable of British contributions to the arts has been reinforced by observation in America, where, as an article for export, it seems to have again proved its excellence. Some day an account must be given of the English tradition in America and of the translation of the ideas of Langley, Repton, Price and Gilpin along the James River, up the Hudson and in New England. This must be done before the great estates of the Eastern seaboard go the way of their English counterparts, as they will do, in spite of the efforts of the National Park Service—the American equivalent of our National Trust—unless the public is sufficiently aroused.

The author’s original rather cursory estimate of the nineteenth century has undergone considerable revision as the result of further investigations, which have proved that the inventions of our grandfathers and great-grandfathers often possessed great daring and originality. This opinion is based on the discovery that the nineteenth-century revivals were not always mere essays in copyism, but actually productive of entirely new forms and expressions. Our attitude of hasty condemnation may well give way to one of considerable respect as the full story unfolds. More power to those who have begun to encourage an interest in our immediate past !

The author’s attitude toward modern art, architecture and landscape architecture has also changed somewhat as the result of seeing more examples. This has not been surprising to him, nor will it be to his readers, since the movement is avowedly experimental and no one remotely connected with it can be expected to stand pat on opinions formed at an earlier stage of development.

Most important perhaps is the conviction that creative art has a firmer foundation when based on the accumulation of acquired knowledge rather than on intuitiveness alone. In 1937, the author, together with the Belgian landscape architect, Jean Caneel-Claes, wrote a manifesto which contained among its clauses the following;

We believe in the probity of the creative act … the reliance of the designer on his own knowledge and experience and not on the academic symbolism of the styles or outworn systems of æsthetics, to create by experiment and invention new forms which are significant of the age from which they spring.

Time has proved, to at least one of its writers, that this statement should be modified. If one is attempting to grow a rare plant, the natural procedure is to look up the work of previous cultivators in order to pleased is likely again to be foundavoid mistakes, and then perhaps to add a dash of initiative by varying the formula to suit the special conditions of the situation and climate. In artistic development, this method seems also to be useful. May one say with fairness that there are too many architects and others who adopt a “modern” style without regard to its origins or philosophy ? These are the people who are defeating true modernism; they do not investigate enough; they have discarded the older styles without bothering to find out what they represent or the demands of the society which produced them. It is not surprising that the more forward-looking practitioners regret this gap in their training, or that many have now begun to study the methods of past times in order to salvage what may be useful to them in cultivating their artistic growth. There is no reason in the world why this should hinder their use of new materials and techniques, as has often been supposed. The free, untrammelled creator may be an engaging personality, but he may also be out of touch with the needs of the times, and commit some frightful blunder when faced with a situation requiring exact economic, artistic, or historical knowledge.

A professor in an advanced “college in North Carolina who read the first edition of this book recommended that the next one should contain less history and more modern things.” The author’s reply was a quotation from Geoffrey Scott: “That which has once genuinely pleased is likely again to be found pleasing,” and a rejoinder to the effect that, in England at any rate, by far the best work was done over a hundred years ago. The aphorism is all too true, and it is especially true of planning and architecture which are always better when they acknowledge precedent.

“If the modern movement does not achieve recognition in the next five years, it will be dead.” The distinguished head of a modern school of architecture and planning said this recently in conversation with the author. People in his position have had ample opportunity to observe the results of the system; the first courses in modern architecture in America were given at the University of Michigan as long ago as the late twenties. The statement is a considerable challenge to those of us who in the twenties and thirties started out with high hopes and a good deal of faith in the new art forms, and it hovers like the hand of fate over the heads of those even younger people who have recently been trained in no other medium. It is a challenge, however, that can be met. It may be agreed that the modern movement has drifted into many curious forms and mannerisms. If the current mannerist style continues, its death will come from public indifference. “A style for our own times” may not be anything like what we imagined a few years ago: perhaps it should, in fact, be more like what was current a hundred years ago—a meshing of several styles or idioms with entirely dissimilar physical results. In other words, the modernist ought now to be broadening his range, not narrowing it, and trying his hand at all sorts of solutions. In his otherwise delightful book, British Architects and Craftsmen, Sacheverell Sitwell criticizes Wyatt for turning from Greek to Gothic and displaying what the present writer considers a pleasing versatility. To have several ways of building and planning at one’s command ought to be the modern aim as well. “The pleasures of infinite variety” are sorely needed in the modern landscape, and the notions of Sharawadgi, which are mentioned in these pages, and have come much into prominence since the book was first published, might well have a present-day application. There should be no one style of building or planning.

A word should be added on the social aspects of modernism. There is a dangerous fallacy in thinking that a certain kind of architecture or planning is intrinsically “better” than another. From this stems the idea that its widespread use will help to build a better society. But architecture and physical planning have never shaped society; although planners have presumably been shaped by the society in which they live. The Bath and Regent Street that we admire were not the products of a particularly progressive society; and certainly they were not “good” for anyone, except a handful of middle class tradesmen, two or three architects and a couple of earls. On reflection, it will appear that the programme of physical planning is the agent which influences society and that which the programme produces will be determined by what it says and who writes it. Architects and allied technicians must go into community planning—they are badly needed—but while they may help shape the plan, they should not try to dictate its final form. We must beware of the approach of the technocrat, of anti-intellectual reliance on “intuition,” of metaphysical formulae and of the so-called biological or “organic” approach, which may be suitable when discussing the relative merits of fertilizers, but does not belong in the socio-economic process of town planning. When attempted there, as in Wright’s Broadacre City, this approach results in something which could never be built and which no one would want to live in if it were.

So much for the philosophy of the subject. The author’s personal approach to landscape gardening and planning has not changed. First, an eighteenth century understanding of “the genius of the place” is necessary. Then the structure—in which usefulness and aesthetic pleasure must both be considered. Then materials of only the best quality (when they are available!)—this is very important, and it will be noticed that they are put in their proper place, after the grand conception, not before it. Finally, understanding the wishes of the client, whether it is a private citizen or a public committee in New York or London. This formula does not result in mannerism, to the best of the writer’s knowledge and experience.

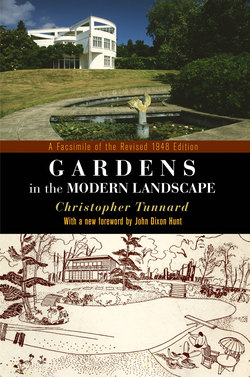

With this opportunity to put the last word first, the reader may be left to the book itself. Except for a slight condensation and a few corrections, the text is unchanged. At the suggestion of several readers of The Architectural Review, some sketches of plants which appeared in that periodical have been included in this edition. The postscript, which originally appeared in the Bulletin of the Garden Club of America, is by Joseph Hudnut, who may perhaps best be described to English readers as Sir Charles Reilly’s counterpart in the United States. Architects and designers in America have gained much from his generous support; not least among them the author, who owes him his introduction to a new field of activity.

CHRISTOPHER TUNNARD.

Tale University, 1948.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The author’s thanks are due to H. F. Clark for help in the preparation of the text and illustrations, to T. Gordon Cullen, Lloyd Flood and L. B. Voigt for sketches, to Arthur Sanderson and Sons, Ltd., for permission to reproduce, as the background to the bookjacket, a portion of their photograph of a wall-paper from the panoramic sequence entitled “Telemachus on the Island of Calypso” printed by Dufour about 1825, to the Studio for the loan of the block on page 92, to Letitia Hicks-Beach for the drawings of St. Ann’s Hill, to Hugh Macdonald for Shenstoniana, to Bernard Leach for information concerning Japanese art, to A. G. Ling and John Piper for photographs, to Raymond McGrath for illustrations from his book “Twentieth Century Houses,” to the Royal Institute of British Architects for permission to use its blocks of the Amsterdam Boschplan, to the Keeper of the Royal Horticultural Society’s Library, F. J. Chittenden, for permission to photograph illustrations in old horticultural works, and to W. T. Steam of the same institution for assistance ivith references and the bibliography. The author also desires to thank Mrs. Combe and L. A. D’A.D’Engelbronner for permission to photograph the gardens at Pain’s Hill and Redleaf and Herbert Felton for the execution of this work. Finally, he records his appreciation of the advice and criticism given him by H. de C. Hastings and J. M. Richards of The Architectural Review, in which magazine a large portion of the book was originally published in serial form, and by M. A. Regan and A. E. Doyle (the latter particularly for the format and lay-out) of The Architectural Press.