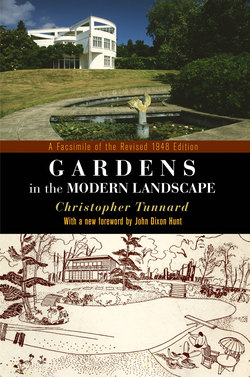

Читать книгу Gardens in the Modern Landscape - Christopher Tunnard - Страница 13

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеLANDSCAPE INTO GARDEN

I—Reason and Romanticism

A GARDEN is a work of art. It is also a number of other things, such as a place for rest and recreation, and for the pursuit of horticulture, but to be a garden in the true sense of the term it must first be an aesthetic composition.

The necessity for keeping this in mind arises from a two-centuries old confusion between the idea of gardens as pure works of art, and as works of art in imitation of nature. When Addison said, “Gardens are works of art, therefore they rise in value according to the degree of their resemblance to nature,” he propounded the most fallacious argument that it has ever been the lot of the landscape artist to try to confute. It was perhaps inevitable that, already using her own materials, the pursuers of this art who had just begun to break free from deep-rooted fears of nature as a tyrannical mother, and who now began to woo her as a mistress, should on occasions have confused the means with the end; even so, it could hardly be expected that Addison’s initial error should have led others down the strange and tortuous paths which have brought the modern landscape architect to his present anomalous position. Painters, poets, novelists, musicians and architects were all dragged through the mire, so it is hardly surprising that the fashionable eighteenth-century landscape gardeners did not emerge with their artistic integrities unstained; the matter for regret is that their counterparts of today have not profited by the experience of brother artists who, in almost every sphere of aesthetic activity, have wiped the mud from their shoes and set off on a straighter road towards a more clearly defined horizon.

The occasion of Addison’s visit to Italy, which roughly corresponds with the opening of the eighteenth century, marked the end of one literary age and the beginning of another. It also sounded the death knell of the old “formal” style of gardening. The next forty years saw the most complete revolution in gardening taste which the art has ever known; our quarrel, however, is not with the influence of that period, but of a later one. The earlier landscape gardeners contributed much to the enlargement of artistic experience—they gave us incidentally the familiar outlines of our present countryside—and although their work contained the germ which gave rise to the subsequent aesthetic malady of gardens, these painters in nature’s materials, as they have been called, were only its harmless carriers.

For an exact diagnosis it will be necessary to examine the development of gardens together with the artistic trends of the last two hundred years. At the beginning of this period, particularly, gardening was influenced by painting and literature in a manner so marked that these two arts have from the first been recognized as affecting English landscape design more strongly than the economic upheaval which was just beginning.* “The Greeks had no Thomsons because they had no Claudes” was an often quoted saying of the latter part of the century, and while English poets formed their taste on a study of Italian paintings, landscape gardeners drew their inspiration from both. A small acquaintance with the literary and artistic thought of the period makes it clear that gardening followed literature and painting fairly closely, and not architecture, as some writers would have us believe. On the contrary, this latter art was influenced by gardens to a certain extent. Certainly the revived cult of the Gothic in architecture first appeared in gardens, into which ruined abbeys and crumbling castles were introduced as likely to induce the feeling of pensive melancholy, considered a highly satisfactory reaction in the spectator of a landscape garden.

This inter-reaction of the governing ideals of painting, literature and gardening began with the enthusiasm for Italian landscape as seen through the eyes of painters like Claude and Salvator, and as elaborated in the writings of travellers who had made the Grand Tour, such as Addison, Thomson, Dyer, Gray, and, later, Horace Walpole. The serene and glowing landscapes of Claude and the romantic savagery of Salvator were thought typical in the first case of the Italian plains and the country round Rome and in the second of the wilderness of the Alps through which the English usually passed, at some hazard to their personal safety, on the journey to Italy. Paintings of both these artists found their way across the water and were praised above those of the Dutch masters in which the classical touch so much admired by the new generation of history-conscious “men of taste” was disappointingly absent. The Italian style was feverishly copied and England became a nation of amateur artists.

Was it not perhaps natural that those who found themselves only mediocre painters in oils and still wished to be accounted as following the fashion should turn to the new style of gardening when it evolved, as a supposedly more facile means of expression? Landscape gardening became the hobby of every English gentleman, and a resulting confusion of ideals was thus perhaps only to be expected.

Top, a pre-landscape garden. Bottom, “… the apparatus of a rude and hearty taste in outdoor amusement.” From “Systerna Horticulturæ,” J. Worlidge, London, 1677.

The point to make clear is that the seventeenth-century formal style, degenerate and cluttered with absurdities of decoration as it became, was an art in a sense that the landscape style was not. Though bound by innumerable sets of rules, an artist like Le Nôtre was at liberty to indulge his creative instincts without the necessity of producing a representational design. Within the limits of his walls and hedges there was room for free play of the imagination. The landscape gardeners set themselves no limit; the boundaries of their garden were the shores of England; but they were fettered by the conventional necessity for pictorial imitation.

What other features can be marked as revealing the essential nature of the landscape movement ? To begin with, it did not arise simply “as a reaction to the excessively dull formal style of gardening,” as the change is passed over by many of the gardening histories. Every reaction is caused by new ideas; without them each generation would remain content with the manners and makeshifts of its forefathers. Art follows the inventions of science, the changing standards of economics, and the adventurous feet of pioneers of exploration, and the period under review was not lacking in all three. We have begun to see how gardening was influenced in the highest degree by the arts of painting and literature. The “pleasing, horrid and enchanted” Chinese garden of which Europe in the early eighteenth century had romantic but unauthenticated descriptions, remains the unknown quantity in this process of change. But such major events as the passing of the Inclosure Acts, the economic upheaval loosely referred to as the Industrial Revolution, the exploration of China and Japan by Jesuit missionaries, and the new interest aroused in the history of the Middle Ages among a class which hitherto had only been appalled by its barbaric aspects, all played their parts in the determining of the new landscape.

This landscape, before being taken into the garden and developed outwards from the house windows, already existed in the imaginations of men of taste, and without its help our Kents and Browns could hardly have made the rapid strides they did in public favour. Brown’s ridiculous clumps and mounds would have been laughed out of existence a good deal less laboriously than they were removed a generation later under the direction of Repton, had they not been softened by the background of trees which landowners had planted, frightened by the denudation of the countryside of timber used for shipbuilding and the development of towns during the reigns of the Tudors. Evelyn’s Sylva had made a plea for the replacement of the national forests as early as 1664, and up to the end of the first third of the eighteenth century, when the wealthy classes had profited by his example and increased the stock, in almost every gardening and agricultural treatise one reads a plea for the replenishment of natural resources. “Improvement” was an accomplished practice in Restoration times before being recognized as a fashionable one in the age which followed.

“Perhaps the landskips of Poussin are the best instructor which a gardener of genius and taste can follow” (Essay on the Different Natural Situations of Gardens : Samuel Ward, 1774). Above is Nicholas Poussin’s landscape, “Phocion,” illustrating the qualities of “picturesque” composition which were to be translated into the eighteenth-century garden.

Other existing factors helped the bold Kent to “forge a great system from the twilight of imperfect essays.” The stiff brick-walled gardens of William III and his gardening queen had been relaxed at their margins by the introduction of grilles and iron railings, imported, together with the taste for pug dogs and pineapples, from the “Dutch morass,” and these former, with the help of the new gates of wrought iron, also introduced by William, enabled the eye to glance through to the plantations beyond. What more inevitable than the transition from the half-wall to the railing and thence to the ha-ha, a sinking of the ground in the form of a ditch, at this time to be seen in France where it formed part of a system of military defence ? And once the wall was down, there was no ignoring the landscape; something had to be done about untidy woods and fields that could be seen from the parterre. Kent’s famous leap, therefore, had it not been merely a figure of speech, would in any case have called for small athletic prowess.

The hint of French influence in an art considered so unreservedly British in origin, has not so far proved very disturbing to horticultural historians. But Johnson,* whose information is usually reliable, mentions Dufresnoy, the successor of Le Notre, as being a creator of landscape parks in France in the year 1700, which is at least a decade before they were attempted in England. According to this author, “his example was only admired by his countrymen and not followed.” Any of Dufresnoy’s works might have been seen by Addison during his travels in France before the historic essays were written. One would hardly like to accuse the French public of having seen the landscape garden, dismissing it as altogether ridiculous and illogical, and sending the device that made it possible over the Channel to confound the English, who might be depended upon to play the idea to death while its Machiavellian originators in the wings laughed up their elegant, silken sleeves. It is, however, significant that later, when the French introduced Chinoiserie to Europe, they were inclined to restrict the innovations to garden architecture, tea pavilions, porcelain guinguettes and the like, and to disregard in great measure the Oriental abhorrence of avenue planting in straight lines. It is fairly safe to say that the majority of the French people remained faithful to the straight line even at the end of the eighteenth century when the cult of “zigzag shrubberies and wheelbarrow mounts” was at its height in Europe.

Not so the English. “Is there anything more shocking than a stiff, regular garden?” asks Batty Langley in 1728, and proceeds to add weight to the claim by diversifying his own creations with winding valleys, dales, purling streams, serpentine meanders, enclosures of corn, wood-piles, precipices, cold baths and cabinets, to name but a few of the fifty odd component parts of “a beautiful rural garden.” Regularity is a term which could scarcely be applied to scenes which included all the appurtenances of the old gardens, together with some of the new, and with the paraphernalia of rusticity thrown in. In this last he was anticipating the Wordsworthian ideals of rural beauty, but it was an early stage at which to confuse still further the imitators of Claude and Salvator, in whose paintings this quality had not so far been applauded. Doubtless their followers were quick to see in Lorraine’s The Ford and similar works the symbol which they must at once have hurried to find.

The gardens of Langley, Switzer, Addison, Pope† and Bridgeman, if it had not been for their medley of styles (Addison saw no reason why the Chinese and Queen Anne gardens should not be amalgamated in harmony), were by reason of their transitional nature more closely related to our present-day compromise of formality and informality than anything in the two hundred years between. The decorative scroll work of the parterre garden had been done away with during the reign of Anne, who had the parterre at Windsor covered with turf. Thus the ground near the house remained geometrical, but plain, and must have approximated to the modern terrace. Beyond lay “formal” gardens, usually with basins of water and fountains prominently displayed, and beyond that again the wilderness, albeit a wilderness more productive and entertaining than Elijah’s. Menageries, mirrors, waterworks, cones of fruit trees, and bird cages, were all relics of the age of William and Mary and of Louis XIV: the apparatus of a rude and hearty taste in outdoor amusement, soon to be superseded by the affectations of sentiment. The plan of Pope’s garden made by his gardener Serle in 1744 is typical of the more restrained layouts of this time.

But whereas the tendency of the future will probably be away from “natural” gardening towards an architectural style, that is, away from unplanning towards conscious and balanced arrangement, the swing in those days was in the other direction. It is well known that during the dictatorships of Brown, Wright, Holland and Eames, flowers and flower-beds were practically abolished from English gardens. Such frippery would have disgraced “by discordant character the contiguous lawn.” Yet the earlier landscapists had no such ruthless ideas. They had as yet few theories about colour, although they had been forced to cultivate a rather unwilling taste for the sombre reds and browns of autumn by academicians of the day, and were particular about the distribution of light and shade, which Kent effected by means of evergreen and variegated shrubs. Flowers were still to them the “wholesome herbs” of Shakespeare, in spite of the findings of expeditions to America and China; ignorance of the cultural requirements of new species at this time led too often to failure and distrust of any but the better-known favourites, “the jessamine, violet, lily, gilly flower and carmine rose.”

The beginnings of irregularity : from “New Principles of Gardening,” Batty Langley, London, 1728.

The flowers with which Shenstone adorned his ornamental farm were of this kind. One can regard Shenstone, poet, essayist, and man of taste, as a typical artist of the first phase of the landscape movement. He was, of course, an amateur, but then some of the most admired of landscape gardens, Hagley, Persfield, Stourhead and Pain’s Hill, were laid out or developed by amateurs, with the great Price and Knight leading the host of gentlemen turned gardeners. He lacked pretension to architectural knowledge, in an age when every man was his own architect; he could never have achieved Kent’s perfect little temples at Stowe, for instance; but without this, his poetic and pictorial gift sufficed in abundance for the charm of “The Leasowes,” which he laid out to the admiration and envy of his many friends. Apart from the regrettable occupation of the place by fairies, whose presence, together with his reputation for indolence, have always detracted from a general appreciation of their author’s serious intentions towards art, the pictorial arrangement of the woods and fields, the grouping of ornament, and the management of water (of which we have exact descriptions), represent the culmination of all the confused gropings of that time towards a consistent technique. Shenstone had imagination and created pictures; the garden is a series of them, compositions in melancholy, pensiveness, and (we cannot judge, but are prepared to take another’s word for it) “sublimity,” the three tenets of his artistic faith, founded upon a study of Burke and the painters. “Pleasing the imagination by scenes of grandeur, beauty and variety,” was the sum of his demands of the garden as a whole.

For the reason already given and because of a lack of money, Shenstone left “The Leasowes” remarkably unadorned with buildings. On his arrival “he cut a straight walk through his wood, terminated by a small building of rough stone; and in a sort of gravel or marlepit, in the corner of a field, amongst some hazels, he had scooped out a sort of cave, stuck a little cross of wood over the door, and called it an hermitage; and, a few years after, had built an elegant little summer-house in the water, under a fine group of beeches” (which was afterwards removed by Mr. Pitt’s advice). He had not, Graves goes on to say, “then conceived the place as a whole”; when he did he was far-seeing enough not to crowd the scene with bricks and mortar or to dot the open space with clumps of trees,* but

“taught the level plain to swell

In verdant mounds, from whence the eye

Might all their larger works descry,”

and was careful to frame his vistas on the neighbouring landscape, instead of some object near at hand, as Kent and Hamilton were content to do. Though reputedly always in debt, he managed to embellish his grounds on a mere £300 a year, while Hamilton at Pain’s Hill, an estate modelled from the pictures of Poussin and the Italian masters, is reputed (no doubt with exaggeration) to have spent forty thousand pounds on the grotto alone.

In Unconnected Thoughts on Gardening, which has been already quoted, the technique of the artist is revealed. Almost alone among his contemporaries, Shenstone grasps the principles of form in their widest implications, and suggests the modern method of planning in a single sentence. “In designing a house, and gardens, it is happy when there is an opportunity of maintaining a subordination of parts; the house so luckily placed as to exhibit a view of the whole design.” Price, hailed as the originator of our present-day gardens, said very much the same thing. But Shenstone’s chief claim to fame among his contemporaries and the generations immediately following lies in the remark, “I think the landscape painter is the gardener’s best designer,” which was later widely quoted from Unconnected Thoughts as being in direct opposition to Addison’s pronouncement on natural beauty. This remark has been attributed without very good foundation to Kent, but Graves says that, although Kent must have been aware of its implications, Shenstone was the first to make it public. He died in 1763 unconscious of posthumous fame in gardening and in literature, where he is now chiefly remembered as a precursor of the Romantic Movement. His “native elegance of mind” has always had an appeal for the French and his taste for elegiac fragments on urns and seats was not long in finding itself echoed in their gardens. Ermenonville was known as “The Leasowes of France” and contained an inscription to the poet’s memory.

A view of Shenstone’s garden at The Leasowes. “One can regard Shenstone, poet, essayist, and man of taste, as a typical artist of the first phase of the landscape movement.”

THE GROTTO A MANIFESTATION OF THE TASTE FOR “AWFUL BEAUTY” IN THE EIGHTEENTH-CENTURY GARDEN

VAUX-LE-VICOMTE

From France, where as a frame for sculpture or a shady retreat the grotto exists to grace the formal style, it was imported into England and became the toy of Evelyn and his contemporaries: later the rocky cave beloved of Salvator…

CLAREMONT

… finding its home at last as a means of escape to Arcadia in the gardens of the pictorial landscape style.

PAIN’S HILL

Here in the horrid gloom society shuddered with the poets. An elevating pastime ? Yes, for beauty+horror = sublimity.

OATLANDS PARK

For upwards of 100 years the grotto was part of the background of English social life. This one contained a bath, made for the, Duke of Newcastle late in the 18th century. Each of the four chambers had a dominating shell motif, each passage its shaft of filtered daylight. Convex mirrors, the skeleton ribs of epiphytic fern, bright mineral ores and fragments of Italian sculpture were composed to form a design of such complexity that it occupied a man and his two sons for five years in its construction. The grotto was recently destroyed.

SAINT ANN’S HILL

As a final example, a garden house with stalactite ceiling decorations, symbolical of that translation of garden romanticism into the sphere of architecture which was to affect so disastrously the architecture of the nineteenth century.

II—The Verdant Age

We enter upon the second half of the century with an awareness of the passing of rationalism—“the pleasure of being able to understand, the easy sense of simple orderliness, a smooth balance in ideas as in forms”—and the advent of a quickening sentimental feeling for the past, for exoticism and for the macabre. Poets now hymn their lays “by Tigris’ Wandr’ing Waves,” and the indigenous shepherdess of Shenstone’s inspiration becomes the Persian Maid of Collins. Nature is worshipped more fervently than ever before, but she is beginning to be considered apart from her discoverers, the Salvators and Thomsons. The latter in the concluding parts of The Seasons even finds in her aspects other than those of serenity, savagery and universal omnipotence, while the disillusioned author of Verses Written in London on the Approach of Spring makes bold to question the capacity of the unchallenged masters:

“Can rich Loraine mix up the glowing paint

Bright as Aurora ?… Can savage Rosa

With aught so wildely noble fill the mind,

As where the ancient oak in the wood’s depth

… deserted stands ?”

The painter’s conception of landscape having by this time become widely known, it was beginning to be recognized by a few as slightly artificial, selected, and untrue; in fact, though it was undoubtedly good art, there was just a possibility that it might be bad nature. The artistic pedestal was being removed and the goddess set upon her own feet.

Here is the root of a growing trouble.

We hurry through the intervening years, dodging the shaven hillocks and close-planted clumps of Brown, and passing with difficulty along the zigzag paths of Chambers’ Eastern shrubberies, with nothing more interesting to stay us in our flight than a profusion of temples in conglomerate styles. Gothic and Oriental race neck and neck for supremacy, with Classic, a pale shadow, struggling behind. But when gardens belong to nature and no longer to painted nature, these edifices cease to serve their purpose, existing only to mock the new and echo a vanishing style. Symbolism is dying, and devotees of the new cult seek to justify the use of grottoes, caves and ruins by concealing in them cattle sheds and herdsmen’s hovels or by designing them (how, we are not told) “in a manner naturalized to the trees and woods.”

Top, a “picturesque” cottage for a retainer at Oatlands Park. Left, Kent’s park at Claremont, as improved by Brown. The present mansion is reputed to be the only one ever built by Brown, although he altered many; here the architectural magnificence at which he aimed has somehow not materialized. In 1850 it was possible to write that “… its present royal possessor … greatly enlarged the estate by the purchase of adjoining lands. These purchases were made to frustrate the speculating intentions of certain persons who were contemplating the erection of buildings around Claremont; by which its domestic privacy, and sweet retirement, would have been destroyed.” The irony of these remarks today will be appreciated after a glance at the photographs on pages 151 to 154.

This period is the age of Lancelot Brown, who held undisputed sway, except for the jealous bickerings of Chambers, from 1750 until his death in 1783. This man, who refused work in Ireland because he “had not yet finished England,” was a tremendous influence and not altogether an unmixed blessing to the country he was so zealous in “improving.” He could rise to magnificent heights, as at Blenheim, which has always been considered his masterpiece, but he could also stoop so low as to indulge in constant repetition and to alter ground unnecessarily for the sake of performing this fascinating work. To smooth a rocky crag into a bald hummock was his especial delight, and one can only surmise that having observed the magical transformations achieved by levelling and grading, and lacking any satisfactory theory to justify his prodigious activities, this aspect of his work became an obsession with him in the manner of the bottle with the toper. In other words, he was far from being an artist, and his clients suffered for it. We, to whom the work of all eighteenth- and nineteenth-century landscapists appears softened by the mossy layers of time, are thankful to Brown and his followers for their tree planting, though even today their remaining overcrowded plantations of ill-assorted specimens bear testimony to a lack of skill in grouping.

The demand for Brown’s services was enormous, not because he did good work but because improvements were the fashion. His genial manner won him popularity, and the literary and grammatical allusions with which he invariably illustrated his ideas no doubt helped to produce, in a gullible public, the sense of a competence which he was in fact far from possessing.

The landscape influence was felt in every garden in the land, from the surroundings of the palace to the enclosure of the smallest Thames-side villa. The two-acre estate of Squire Mushroom, the imaginary butt of Francis Coventry’s wit in 1753, perhaps gives no very distorted view of the extremes in which landscaping could be taken:

“At your first entrance, the eye is saluted with a yellow serpentine river, stagnating through a beautiful valley, which extends near twenty yards in length. Over the rim is thrown a bridge ‘partly in the Chinese manner,’ and a little ship, with sails spread and streamers flying, floats in the middle of it. When you have passed this bridge, you enter into a grove perplexed with errors and crooked walks; where, having trod the same ground over and over again, through a labyrinth of hornbeam hedges, you are led into an old hermitage built with roots of trees, which the squire is pleased to call St. Austin’s cave. Here he desires you to repose yourself, and expects encomiums on his taste: after which a second ramble begins through another maze of walks, and the last error is much worse than the first. At length, when you almost despair of ever seeing daylight any more, you emerge on a sudden in an open and circular area, richly chequered with beds of flowers, and embellished with a little fountain playing in the centre of it. As every folly must have a name, the squire informs you, that ‘by way of whim,’ he has christened this place ‘little Maribon,’ at the upper end of which you are conducted into a pompous, clumsy, and gilded building, said to be a temple, and consecrated to Venus; for no other reason which I could learn, but because the squire riots here sometimes in vulgar love with a couple of orange-wenches, taken from the purlieus of the play-house.”

The English garden in France … and the Chinese : from “Plans Raisonnés de Toutes les Espéces de Fardins,” Gabriel Thouin, Cultivateur et Architecte de Jardins, Paris, 1820.

In the above we can identify the lake as the work of Brown, the hermitage as Shenstone’s, the temple as deriving from Kent and the flower garden and grove as relics of good Queen Anne. Coventry concludes by describing a villa as “the chef-d’œuvre of modern impertinence,” an epithet which points to the fact that the planning of villa gardens was looked upon as unimportant. The same attitude is regrettably prevalent today.