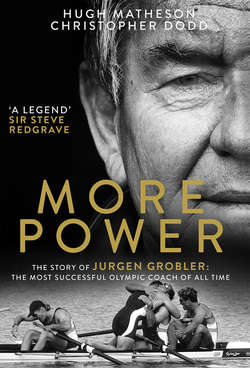

Читать книгу More Power: The Story of Jurgen Grobler: The most successful Olympic coach of all time - Christopher Dodd - Страница 12

Оглавление4

THURSDAY 9 NOVEMBER 1989

East Berlin

‘Grobler was the most curious one who reads, listens and tries everything.’

– KLAUS FILTER

Jürgen Grobler’s status among the East German team coaches had risen because the crews he was responsible for performed well and his application of the methods and science of rowing and sculling was as good as anyone’s.

In the months after each Olympics the GDR trainers, medical researchers, boat-builders, biomechanics, dieticians – all the members of the Committee – wrote reviews of the training and results of the past four years and made their proposals for the next cycle to be presented and discussed in a grand wash-up meeting, usually held in the following January. It was at this meeting that the next batch of gold-medal times were predicted and the baseline set for the trainers to work from. In 1981 it was the route map from Moscow to Los Angeles, with three world championships as marker posts along the way.

The men’s and women’s teams were run separately, although they shared most of the facilities. Hans Eckstein took charge of the men’s team and Grobler became director of the women’s squad. Eckstein was six years older than Grobler and, like him, a graduate of the German College of Physical Culture in Leipzig. Unlike him, Eckstein was a two-time national champion in eights and fours. Grobler rowed competitively from the age of 16 up to the student championships, but his rowing had been subordinate to his teenage dream of becoming a cameraman, which was quelled when he realised that fewer than four film graduates were required each year in East Germany. But the GDR was offering hundreds of openings for graduates in sports science. Strategically wise even in his teens, Grobler responded to the laws of supply and demand in what was, nominally, a purely command economy when, aged 19, he enrolled at Leipzig.

Ten years after his graduation Grobler was one of the top two operating coaches under Dr Theo Koerner, the chief executive, whom he regarded as one of his greatest influences. The other was Eckstein who had been his instructor during teaching practice at SC Enheit Dresden. That Jürgen took the director role for the women’s squad is attributed by some to the canny ‘Schweine Schlau’ character that realised the probability of more international medals equalled the reward from a grateful state of a higher standard of living. He was expected to produce consistent success in the six Olympic events available. At the 1979 championships East German women had won three golds and three silvers, and at the 1980 Olympics one better with four golds, a silver and a bronze, so this was a daunting target and in his first season as director the team flopped, if only by its own dominant standards.

The 1981 world championships returned to the Oberschleißheim Olympic course near Munich, and the conditions were benign. The women’s medal yield dropped sharply to one gold by the coxless pair and three silvers. Two boats missed medals. With the huge number of athletes being given the best possible training to compete for seats, it was particularly galling that the eight finished fifth, just ahead of Great Britain who enjoyed no investment of any kind.

Jürgen applied the standard selection rule for sculling boats, allocating the winner of the trials to the single boat. Sylvia Schwabe won the 1981 trials and inherited the single-scull slot that had been graced for six seasons by Christine Scheiblich, who had won the first women’s Olympic sculling medal in 1976 and was unbeaten abroad until her triumph in Moscow. Meanwhile, expectations for Schwabe were high and disappointment deep when she was beaten into fourth by, among others, the British sculler Beryl Mitchell who – to add insult to injury – was a lightweight and would have been too short and slight to qualify as a top-tier athlete in the rigid East German system.

As director of women’s rowing, Grobler had no responsibility for any particular crew. He was, therefore, slightly distanced from the failure. A high proportion of the 1980 Moscow women’s team, having held off the selection challenge from below despite the large number of candidates, had then performed badly. Grobler’s disappointment will have lingered only a few hours before he subjected his programme to severe analysis. In such circumstances his conviction that quality of training matters more than quantity was developed. Crews from the West, who had perhaps learned to fear the East Germans and regard them as well-nigh unbeatable, would be amazed to watch them paddling light on the way back to the rafts after a warm-down. The boat would bang from side to side and the crew slide back and forth with no care for the movement of others. It was the opposite of teamwork. It was ragged, like an army that has thrown away its weapons. Most pressure work at less than race pace was sloppy and contradictory to the excellence of competitive performance. In the men’s squad some of the distance rowed served to keep the oarsmen tired and out of trouble rather than to go faster in races. They behaved as military conscripts behave: did what they were told without engagement or enthusiasm and let standards fall the moment authority is out of sight.

In contrast, western athletes were volunteers who had given up most of their free time and sacrificed earnings, comforts and a social life in order to compete. Their energy was spent to the point that they could not climb the stairs at night without concentrated effort. They could afford little more than a couple of hours’ training a day six days a week, and so coaches made their lives as easy as possible by looking for constant rhythm and unified movement. Western athletes thus felt almost insulted that the crews who had all the apparent advantages, handed to them by a political machine that yearned for success, could treat the enterprise with such disdain.

The East German women were never as bad in this respect as the men, but they still treated their boats and their kit as if it was someone else’s property in which they had no interest. Grobler wanted a shift of attitude and character, and gradually he obtained it. Rather than increase pressure on the West, and the Federal Republic in particular, Grobler looked east. After all, it was the Russians who had pushed his crews down the table. The Soviet Union had suffered insult in their 1980 ‘home Games’ in Moscow, where the gold medal score was four to one in East Germany’s favour, and so they had doubled their efforts, engaged in systematic doping of athletes, and used every advantage in a most cynical manner. At the 1981 championships, the Soviet Union took four of the six women’s golds to East Germany’s one, and in 1982 it was five to one. The Soviet Union was drawing on a population sixteen times greater and investing the equivalent of the GDR national programme in each of its satellite states.

The science was also, in effect, the property of the Soviet Union. When the German Democratic Republic was created out of the Soviet zone in 1949 the occupying force removed machinery and productive resources from German factories as war reparations and continued to regard the Warsaw Pact satellites as colonies to be plundered at will. All of the science developed at the Sports Institute of Leipzig had to be transferred free of charge to Moscow. Whatever the Germans had learned of the benefit of synthetic testosterone to those enduring heavy training, the Russians had to be told. The Soviet Union had a more cynical view of synthetic assistance: ‘anything that helped was a good thing, a good thing was better if you doubled the dose’, regardless of whether or not the rest of the world had banned it.

Grobler’s task was to get back ahead of the nation that had significantly less regard for the welfare of its athletes or international law. He could not simply raise the dose of training and testosterone to match, and hope that he could find enough athletes from a population of sixteen million to beat the best selected from 260 million.

Grobler has said recently that he thought the GDR was overtraining at that time. His experience told him that he should monitor performance daily to be aware of the dangers of pushing athletes too hard. The sloppy, ‘couldn’t care less’ style of the men when they were not racing was the outcome of thousands of kilometres on the water each year. Increasing the load would lower the quality of the work still further. He also knew that the synthetic testosterone given to the women was at the upper limit of what would be helpful. Women were showing the effects of permanently deepened voices, burgeoning body hair and – according to Brigitte Berendonk, a West German shot-put champion, and her husband, the microbiologist Werner Franke – markedly increased libido. In rare cases, mental instability was an added risk. The strongest, top-tier women may have had more useful bulk and endurance strength, but they themselves were beginning to question the balance of doping and training.

Grobler, staying in character, analysed every aspect of the training and racing programme and then improved the quality of work by making each part count for more. It is still his mantra today. When he growls ‘more power’ through the megaphone at his crews he is not simply calling for more kilowatts of energy but for better application of whatever strength the athlete has left. He wants the contraction of a muscle to translate directly, with minimum slippage, to lever the boat past the point at which the blade locks into the water. His exemplar was Christine Scheiblich who had been the women’s single-scull champion in Montreal. Klaus Filter tells how one of the difficulties that humans have with boat propulsion is that as the rower reaches the end of the recovery phase of the stroke and is preparing to put his blade into the water, he concentrates his weight onto the balls of his feet while pushing against the foot stretcher. For a moment this negative force is pushing the stern down and stopping the hull before the blade is locked on and the oarsman is pulling the boat forward again. Stopping the boat at the catch is universal except in rare cases like Scheiblich’s. Her timing at the catch was proved to be perfect in every type of test that Filter could devise. Scheiblich was one of the weakest athletes in the team and yet she won all her world championships races by large margins. The first Olympic final for women scullers in Montreal was one of the closest and untypical when the American Joan Lind chased her to within half a length. Scheiblich was followed by Thomas Lange and a few others on whom Grobler has modelled the ideal stroke. He has since asked athletes to treat the foot stretcher, which fixes all the thrust of the rower as the oar is levered past the pin, as if it was as fragile as an eggshell. He wants the power to build off the stretcher, not be applied with a macho bang. More power is to be used to make the boat go fast, not just to build big shoulders.

Grobler was known, then as now, as a man in constant search for the different angle, the unexpected factor which would make a difference to boat speed. Although he had worked closely with Peter Schwanitz and Filter throughout his career and knew the biomechanic’s and boat-builder’s reasoning and science as well as his own, he was aware that parallel work was being carried on in the West. After his eight had finished third in 1982 in Lucerne, he bought a new eights shell from the manufacturer Empacher in West Germany. Although he asked his sweep oarswomen to train in it for months, they were unable to make any sense of it. Percentage gold-medal times were well off the mark. As Filter told him before and after the extremely expensive experiment, the way the East German boats were designed and built and the way the East German athletes were taught to row was compatible. The Empacher was designed for a different, more universal style, with more compression of the legs and less reach of the body and arms. In the language of Das Rudern, it was made for a Kernschlag not Schubschlag style.

Characteristically Jürgen learns from mistakes like that and absorbs the new information into his formidable bank of rowing experience which, after nearly fifty years as a professional coach, cannot be matched. The following year, in the 1983 world championships, his team earned the result he wanted: four golds and two silvers put the East German women back on top of the table. The Russian flare was waterlogged.

* *

Grobler entered the final year of preparation for the 1984 Los Angeles Olympics with every expectation of being able to repeat the success of Moscow. The preparation went well, with altitude camps in Mexico and Silvretta on the Austrian–Swiss border, and a European season of regattas that would culminate in Lucerne on 7–9 July. Then without warning, on 8 May 1984, the Soviet Union declared that it was so concerned about the commercialisation of the Los Angeles Games and was so worried about team security that it would withdraw its competitors. Two days later East Germany and Vietnam announced that they, too, would withdraw.

Whatever your position in East German society, whether one of the chosen nomenklatura or a factory worker, you could not protest or gainsay an edict from the Politbüro, which ran the state from the top to the very bottom. For the Politbüro to be denied the chance to exhibit German superiority in competitive sport was as bitter for its members as being cut out of a chance of Olympic glory was for 20-year-olds who had spent four years and 50,000 km at the oar. The instruction came from Moscow, intended as a Cold War strike against the US president, Ronald Reagan. It was a plain tit-for-tat response to the American boycott of Moscow four years earlier.

As a consequence, rowers who did win gold on Lake Casitas, outside Los Angeles, speak of their results at Lucerne regatta beforehand as the real marker of their quality. Martin Cross – who rowed at bow in the four stroked by Steve Redgrave and that won the first British Olympic rowing gold since 1948 – always takes a second breath to speak of beating the East German coxed four in Lucerne. The GDR, whether it won or lost, was the benchmark for all international rowing events in those years.

From the announcement of the GDR’s withdrawal on 10 May 1984, Grobler knew that there was no chance of a change of mind. He set about measuring how much improvement in standard times was likely at Seoul in 1988, and then refined his programme to ensure that his cohort would be in the lead once more.

Through all these years he had been drafting new faces into the senior group, most of whom had won gold at world junior championships. There were not enough places in the senior squad to accommodate everyone with world junior championship golds who might have expected to rise to senior success, and Grobler was obliged to cut those who would not make the step up. All who experienced it said that Grobler was clear and kind in the way he told people that they were about to be dropped from a programme in which they had striven ridiculously hard and from which they, their families and schools, had benefited. He had no need to blend youth and experience because those in the lower women’s ranks had been exposed to international racing from the beginning and fought their way into the top group by winning hard races. They knew about survival from experience.

One of his juniors, Jana Sorgers, was picked up during her eighth year at school as a naturally athletic girl who stood at 1m 82cm. She was offered a place at SC Dynamo in Potsdam, near Berlin. This involved living at the clubhouse, with trips home every fourth weekend. At first she was homesick and asked to return to her family. Her mother argued that hers was an opportunity not to be missed. She knew what her 14-year-old daughter could not know: that the life of an elite athlete would open a whole new world for her. There were also benefits for the family, including a better flat and access to higher-paid employment. A compromise was reached: Jana was allowed to spend every weekend at home, and her projection into the sports training elite provided a lift for the Sorgers family.

Jana’s schoolwork continued at SC Dynamo through teachers seconded to the club, but the emphasis was on training, perfecting and cementing the movements of her new sport. For two years her training load was increased steadily. Racing and testing was continuous, and culminated in her winning trials for the junior national team to race in the championships in Jönköping, Sweden, in 1984. The East German juniors were even more dominant than the seniors, partly because few other nations were organised to select composite crews drawn from across the country. When composites were formed, the training period was short. But in the GDR the team was being built from the earliest stage possible. Sorgers won again in the 1985 junior championships in Brandenburg, and consequently transferred to the senior squad, directed by a coach she had not come across before: Jürgen Grobler.

When asked if Grobler had favourites among the women’s squad, she admits that she was perhaps one of them, but the relationship did not extend to him doing any favours for her or anyone else. He was supportive when any athlete was struggling or under-performing. He would modify the programme and give the athlete every chance to recover their form, but if improvement didn’t come, he dropped them. He had a gauge, which became more sophisticated with experience, based on his understanding of psychology and physiology on whether there was another good championships performance to be had from an athlete. If he concluded they could not raise their game for another great effort he would end their careers gently but firmly. He knew the cost in physical training and emotion of a gold medal and he hated a futile enterprise.

All juniors started out in sculling boats. After the basic skills were mastered and their bodies had matured, they switched to sweep rowing. The very best remained in sculling boats because the coaches assumed that international sculling events would be filled with the best athletes from other countries. Sorgers had won twice at world junior championships: in the quadruple scull at the age of 17 and in the double scull a week after her eighteenth birthday. She took the stroke seat in the senior quad in her first year after moving up. This was unusual but not unheard of. Her recollection of the training is that the quantity was massive despite Grobler’s mantra of quality being more important than quantity. She remembers how, when he came to watch a session managed by her crew coach, Jutta Lau, everyone perked up, pulled harder and polished their style. He was a hugely respected and slightly frightening figure.

The winter work Grobler insisted on was exhausting, particularly the cross-country skiing. At altitude the combination of thin air and side-by-side track racing left even the most athletic gasping. The importance of this exhaustion was to root out the weak in body or will. For the survivors there was the ‘assistance’ available by means of Oral Turinabol. Sorgers opined that the blue pills were given to and taken by the whole squad. If they wished to survive in the privileged world that they had come to expect, they took the pill. It was so much a part of the system and morality that the question of side effects that obsessed critics never occurred to the athletes. The long hours of Marxist-Leninist discussion had a purpose and effect. They believed in their coaches as agents of a state that, to them at least, was benign and extremely generous.

Sorgers says that the synthetic testosterone was used only during periods of very heavy training and was accompanied with the explanation that it was to assist a more rapid recovery. As this was perceptible and could be measured by the coaches, it was easy to believe. Nevertheless, athletes were aware that the drug was regarded as illegal. All East German rowers gave regular urine and blood samples which were tested at Kreischa near the Czech border to determine that no trace of the synthetic testosterone remained after the little blue pills had been changed from Oral Turinabol or Clomiphen to a harmless placebo. The accuracy of the tests resulted in no East German rower testing positive, ever. It is a nice irony that today the laboratory at Dresdner Straße 12 in Kreischa is one of the few approved by the World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA) for tests to catch twenty-first-century cheats.

Sorgers sculled on in the quad to Atlanta in 1996, where she and her coach Lau represented a united Germany. Lau’s programme was the same as her old East German one although, Sorgers said, ‘it felt much harder.’ Because it did not include any synthetic testosterone.

* *

While Jana Sorgers was going for her second world junior championship in 1985, the seniors gathered at Hazewinkel in Belgium. The boycotters of the Los Angeles Olympics were all back in the boat and the East German women resumed their position at the head of the medal table, with four wins, a second and a third, while the Soviets took one gold and one silver. Jutta Lau retired from competition after several illustrious years as a prominent sculler and was fast-tracked into Grobler’s coaching team. She knew his methods well and was a reliable disciple.

For the 1986 season the 18-year-old Sorgers, with two junior world golds in her kit bag, was transferred to the senior squad in Grünau on the outskirts of East Berlin. She made the top seven in the sculling trials and moved into the quad. She was with a future Olympic champion single sculler, Birgit Peter, and two older women. By now the international federation had extended the women’s racing distance to 2000 metres, and at the world championships in Nottingham the quad racked up a seven-second margin over second-placed Romania. This was a sweet revenge because Romania had evaded the Soviet Union’s Los Angeles boycott by Warsaw Pact nations, and had taken five of the six rowing golds in women’s events there. For Grobler to assert so convincingly that the Romanian success would be countered was part of the realpolitik of his role. Despite this success, Romania’s heavy investment in its women’s programme was to become a force equal to his own.

Immediately after his team missed the libido and booze-fuelled post-championships party to catch its charter flight from East Midlands airport, Grobler set the targets for the 1987 season that would climax in Copenhagen. The programme performed with its customary authority in the early regattas, when Grobler’s super-compensation cycle required his athletes to race without full recovery early in the season. They would compete with measured tiredness at continental regattas, so they had to work harder to win than when they were in the pink. They would then reach the final of the championships with 100 per cent of their available energy, and were able to race more easily and improve their position relative to the best crews.

In 1987 the conditions were awful on finals day. Martina Schröter, the single sculler at Copenhagen, raced in such a headwind that she took nine and a quarter minutes to cover 2000 metres and finished fifteen seconds behind the Bulgarian whose lane afforded shelter from the cross-headwind. The women’s double scull of Beate Schramm and Sylvia Schwabe went to the 1500-metre mark in the fastest two places, as expected, and then lost ten seconds after a crab (catching the top edge of the oar under water resulting in a sudden – often dramatic – brake on the boat), fading to fifth. Only the quadruple scull with Sorgers in the bows came good and won.

In all, Grobler’s team took one gold and three silvers, with the eight and the coxed four out of the medals. It was a poor result by East German standards, but he will have calculated the lane differences and known where his preparation or selection was deficient and where it was appropriate to blame the conditions. By this time in his career he was more likely to blame his training programme – now tailored to each athlete – than to assume that the weather or any outside factor was the cause.

The next stop was the Olympics in Seoul. For Korea in 1988 Grobler stuck to his usual approach, calling for quality and applying his objective method of selection. Lau was now personally responsible for the quadruple scull and, although obliged to take the women who finished fourth to seventh in trials, was allowed to allot seats. Sorgers moved from bow to stroke and was made responsible for changes of pace in a crew that – assisted as ever by Filter’s subtle adjustments to the rig – enjoyed nigh-perfect uniformity of movement. Sorgers’ strength off the start and her ability to hold the length of the arc of the stroke while dropping the rate to race pace were two reasons for her crew being able to complete the first 500 metres in 89 seconds, and then pass through the next quarters in 98.5 and 98.3 seconds. This was as close a call as Lau or Grobler could ask for, and when the Russians came from the back to push towards the line, Sorgers raised the pace again to cover the last 500 metres in 95 seconds, a well-nigh perfect race profile. In addition, the East German coxed four and eight won their events. Grobler had delivered again, although his crew coaches took the honours. East Germany’s women had five of Seoul’s six gold medals.

Seoul would be the last Olympic games in which East Germany would compete as a separate nation. For the third time it finished second to the Soviet Union and ahead of the United States. The political point of the country’s sporting prowess had been well made, and now the economic cost of the socialist path was draining the patience of the people, just as it was doing in the other Warsaw Pact countries languishing behind the Iron Curtain. By the time the Olympic family would meet again in Barcelona, the GDR would no longer exist and many of its rowers would be competing for a unified Germany. But as the Olympic flame was extinguished in Seoul, no one knew that. On the long flight home from the Far East, Grobler would have asked himself what his next GDR Olympiad would bring, and what his next trajectory of crew improvement would look like in each of his boat classes – beginning with a world championships in Bled, less than a year away – just as he had done after the previous four Olympiads.

The post-Seoul conference of the East German rowing federation in January 1989 set out the next expected gold-medal times and the training structure required to achieve them, led by the technical director, Dr Theo Koerner. Grobler stayed in his post as director of women’s rowing and prepared his team for Bled in September. He had few new faces, and the experienced team took four gold and two silver medals, including a gold for the coxless four that replaced the coxed four in the world championship programme. He had little to report on his return to Germany because it had all gone eerily to plan. He gave his squad three weeks off and planned the trip to Lake Barrington in Tasmania for the next world championships, scheduled for November 1990.

* *

On the evening of 9 November 1989 Wilfried Hofmann, the president of the East German rowing federation, was seated in front of a big television set at the Columbia Club in Indianapolis. In company with others attending FISA’s international coaches conference hosted by US Rowing, he was paralysed with incredulity at what he saw. Men and women atop the Berlin Wall were attacking it with hammers and pickaxes. Dr Theo Koerner was in a similar quandary as he lay in bed at the Calvary Hospital in Canberra, Australia, having suffered deep vein thrombosis while lecturing to the Oceania Olympic Solidarity rowing seminar on talent identification. In East Berlin, Jürgen and Angela Grobler watched the same scene during a party for a fellow coach, and then drove toward the Brandenburg Gate to see what was going on for themselves. In one extraordinary evening, the GDR vanished before their eyes, and their livelihood hung in limbo.

East Germany’s collapse came about when Günter Schabowski, the government spokesman, botched his announcement of travel visas being made available in the days that followed. When asked on camera when the free visa system would begin, he answered ‘this evening’, thus triggering the opening of the borders to the West. The border police were ordered to lay down their arms. By dawn on 10 November there was still a wall, but no longer a border with the Federal Republic.

Jürgen Grobler, like every East German citizen, would have been reminded from a young age at school and by the state newspaper Neues Deutschland that socialism was right and everlasting, while capitalism was corrupt and destined to end cataclysmically. Whatever he felt deep down, the high-ranking coach was obliged to rub along with the Marxist-Leninist philosophy that underpinned every action of the state. But by 1989 the state was resorting to increasingly desperate measures to stay afloat, and people were apprehensively aware of what was afoot. Soviet newspapers were suppressed because they reported President Gorbachev’s perestroika in too much detail. West Germany was invited to pay for exit visas to allow East Germans to leave. The leavers were branded as troublemakers for seeking a better life on a different path. For the GDR these visas had two benefits: they transferred wealth from West to East and they got rid of the riff-raff.

When the East German bubble burst, the rowers’ training continued toward an uncertain future. The economic system that had supported elite athletes so well persisted for a while as the country moved swiftly to reunification with the Federal Republic. Many rowers and coaches stayed on as they looked about them for what was next, while many suffered from depression. Jana Sorgers was a case in point. After stroking the quad to her fifth successive gold medal at the 1990 world championships in Tasmania, she ‘fell into a hole’ and dropped out of rowing for two years before making a successful comeback wearing a German shirt in Atlanta in 1996. Half of Grobler’s squad went to Tasmania, where they won three golds and three bronzes. ‘Not brilliant, but acceptable’, he would say in another year, but this time the surprise was that his pair and coxless four were beaten by West German crews. The Wall had truly disintegrated.

A year before the Wall fell Ian Wilson, Europe Agent for the oar makers Concept2 (and the enormously successful Nottinghamshire County Rowing Association), was negotiating the sale of hundreds of the company’s new carbon-fibre blades to Klaus Filter, the East’s equipment guru. As Filter checked every single blade with meticulous attention to detail, Wilson casually asked if there was an East German coach who might be suitable for a post at Leander Club in Henley. Filter suggested Grobler as the experimenter among the East German coaches and as the most curious one who reads, listens and tries everything. Wilson remembers Filter and Grobler measuring oars with one-metre rulers and giving them five-metre retractable tape to aid their labours.

After the deal was struck and after the Wall was breached, several senior GDR officials and their wives, including Jürgen and Angela, were invited to the world indoor championships in Boston, Massachusetts. Klaus turned up with a bagful of chunks of the Berlin Wall that he distributed as souvenirs. Wilson brought a bagful of five-metre measuring tapes to the party.

One of the competitors in Boston was Britain’s outstanding talent, Steve Redgrave, and Wilson the matchmaker ensured that Grobler at the very least set eyes on him. What followed was an invitation to visit Henley-on-Thames that summer, where Redgrave was based at Leander Club.