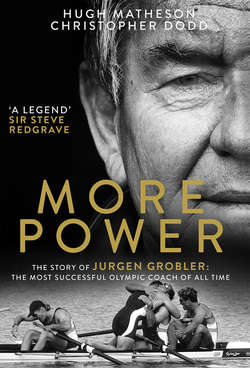

Читать книгу More Power: The Story of Jurgen Grobler: The most successful Olympic coach of all time - Christopher Dodd - Страница 9

Оглавление1

1972

The Munich Olympiad

‘Grobler understood that collaboration with the other key elements would bring the results the state required.’

– KLAUS FILTER

Three-quarters of the way through the final of the single-sculls event at the Munich Olympics in 1972, German political and sporting history was poised on the needle of a stopwatch. West German Udo Hild was holding bronze-medal place by 0.02 of a second ahead of the young, blond East German, Wolfgang Güldenpfennig. At the 1500-metre mark, with 500 metres of the 2000-metre course left to decide, the question was not only which German was the faster sculler, but also which half of the nation had chosen the right path to prosperity and prestige from the ruins of the Second World War. As it happened, Güldenpfennig, the scion of Magdeburg, powered on to take third place by nearly four seconds from the fading Hild.

This result was vindication for a training programme designed not only to place the Magdeburger ahead of the West German, but to put East Germany, at worst, third on the Olympic medal table behind the United States, the world’s richest nation with a population of 210 million, and the Soviet Union with 260 million people. East Germany at the time had sixteen million and a wealth ranking at least twenty years behind its western neighbour.

Güldenpfennig’s trainer was Jürgen Grobler, a 26-year-old assistant coach born and raised in Magdeburg. He had been a clever opportunist to identify Güldenpfennig and take him through national trials to the Olympic podium. He was an interpreter of a method and practice of rowing that informed the entire national effort, a practice that brought East Germany a harvest of sixty-six medals in 1972 – exactly two-thirds of the total won by the table-toppers, the Soviet Union. Grobler had a deeply researched and tested system on which to lean: East Germany’s thrust to pile up medals at the 1972 Games in Munich was a national one-party-state sponsored effort, aimed particularly at the hated Federal Republic where Munich was the capital of Bavaria.

East Germany, the Deutsche Demokratische Republik, grew out of the post-war Soviet occupation zone and derived its authority from the Socialist Unity Party, or SED, and its Politbüro. It began its life as a separate nation in the buffer zone between East and West during the Cold War in 1949, when Jürgen Grobler was a three-year-old growing up in Magdeburg, a town almost completely destroyed by Allied bombers in 1945. It controlled every aspect of his life for the next forty years until it crumbled after its border crossings were thrown open and its people tore down the hated Berlin Wall in November 1989.

Team GDR, as the state would have been branded in the twenty-first century, had done well in the XIX Olympiad held in Mexico City, where a new rowing course was built at Xochimilco at an altitude of 2200 metres above sea level. Mexico was the first Games in which the two Germanys fielded separate teams, and what distinguished East Germany from all its competitors was the analysis to which the Mexico experience was submitted. The training programmes used since Tokyo in 1964 and the benefits and hazards of altitude training in particular were reassessed ruthlessly, and the ‘right’ approach was hammered out at a conference hosted by Manfred Ewald, the president of the German Gymnastics and Sports Federation, the body created to lead the impoverished nation to prestige on the international stage. Sport was a branch, or at least the principal lever, of foreign policy in the Politbüro’s grand plan of 1959, and the Politbüro now had evidence that it was working. Rowing was established at all fifteen high-performance centres to give selected athletes the environment and support necessary to achieve the great things expected of them. The sportsclub at Magdeburg was in addition to the two nineteenth-century rowing clubs in the town that enjoyed good stretches of water on the Elbe for training and racing.

Ewald set the standard of achievement: ‘The objective in Munich can only be to defend the third position won in Mexico and thus to place ahead of West Germany.’ The federation decided that it should refine the number of disciplines in which East Germany could excel and concentrate the effort on eighteen summer sports. Among other excluded sports were basketball and modern pentathlon. In the case of basketball, there was no domestic league to match the Americans and, therefore, no realistic chance of a gold medal. As for modern pentathlon, one-fifth of the points come from a show-jumping competition on a horse picked at random from a paddock of similarly trained animals. Too much is left to chance for a state interested only in winning.

Rowing made the cut, and fifty million East German marks (£12 million at 1977 rates) was pushed into the 1972 Olympiad. By then rowing was a reliable source of medals, and Grobler, aged 23 in 1969 when the Munich plans were laid, was still studying sports science at Leipzig. When he graduated in 1970, he went straight into a post as assistant coach in his hometown.

Dr Peter Schwanitz, who describes himself as a biomechanics specialist, came to know Grobler at that time in Berlin when Schwanitz was demonstrating boat testing at a training programme for elite coaches. Dr Theo Koerner, the head trainer of the East German rowing association DRSV, led the programme and promoted Grobler, enabling him and Sportclub Magdeburg to prosper.

Schwanitz says of Grobler today that he ‘was always very interested in the science of training’, science which encompassed all the specialisms that constitute a full understanding of how a human can move a boat over the required 2000 metres. Whenever a coach deconstructs a race, he or she will look at the split times for each quarter of the course and measure how these vary from perfectly even splits. In Munich, Hild’s race showed 102 seconds for the first 500, 109.7 seconds for the second, 114 seconds for the third and, in spite of the need for a final sprint, 115 seconds for the last 500. Alongside him, Wolfgang Güldenpfennig began more slowly at 103 seconds and gave away a further second (or one boat length in a single scull) to 1000 metres in under 111 seconds. He pulled all of Hild’s lead back to draw level at the 1500-metre mark in 112 seconds and left him wallowing in his wake in fourth place by covering the last 500 in fewer than 109 seconds.

Seen from the grandstand, Güldenpfennig held on to a place in the middle of the pack of scullers from the start and then sculled at a more even pace for the next three-quarters of the race, clocking successively 110, 112, 108.67 seconds for each 500 metres. Hild was quicker to the first and second marks before going progressively more slowly over the second half. While far from perfect, Güldenpfennig was demonstrating the superb endurance and racing nous that marked all the great East German crews of that era, and it was Grobler who had developed that ability in his 20-year-old club mate.

Hild’s race pattern of a quick first half followed by a slow second was standard practice for western nations, and even for other Eastern European states where full-time training should have resulted in greater endurance. The gold-medal winner in Munich, the Russian Yury Malyshev, took eleven seconds longer over the second half. The silver medallist Alberto Demiddi from Argentina was just over ten seconds slower and Hild, as we have seen, was seventeen seconds slower. Güldenpfennig dropped only 7.5 seconds.

Güldenpfennig’s preparation brought him far closer than everyone else to the even-paced splits ideal, and his trainer could claim some of the credit. However, the same pattern becomes evident when analysis is applied to all the East German medal-winning crews in Munich. The Germans were doing something consistently and well. The training programme designed by Dr Koerner was applied across all the performance centres. So Grobler would have started with a paper in his hand that told him exactly how much work was to be done, and at what pace, in each of thirteen sessions a week. The key was to equip him to test his charge on a daily basis to measure improvement and detect overtraining before it became apparent to anyone, including the athlete.

The East German trainers employed the ‘super-compensation cycle’, which is now universal. The athlete is pushed harder and harder for about six weeks of continuous training with no respite and builds up ‘residual fatigue’ so that the recovery between sessions is compromised. Then, when the bottom has been reached and the standard measures are well off the pace, the trainer’s foot is lifted from the pedal and light work is allowed for a number of days. The leap in recovery is marked by sharply improved measurements and, if the system is applied properly, the athlete soon rises above his previous best. Once the improvement is secured, the cycle is repeated with another sustained period of increasingly hard work until the bottom of the graph is reached again and the pressure is relieved to allow another rise, to a new peak.

Some of the East Germans were light years ahead of every other nation in the application of science to measure improvement and to detect decline in the performance of an individual in otherwise full health. This is the application of good science that Schwanitz recognised in Grobler. It was a safeguard against overtraining, and sometimes a complete collapse, that can result when a trainer uses unsophisticated measures to assess how deeply the hard work part of the cycle has bitten into the athlete’s performance, or if he is insensitive to a change in demeanour. Klaus Filter – who, as the leader of the team that developed the GDR fleet of competition boats, knew all the coaches – says that some of the Navy and Army coaches would measure only the number of strokes to the minute and number of kilometres covered to decide that the training had been successful. It was Grobler’s job to ensure that Magdeburg athletes were trained better and more wisely in order to beat the Navy and Army clubs by applying his sophisticated knowledge acquired at the university in Leipzig.

The other ingredient of training athletes better than any rivals was provision of support to enable them to accept the punishing regime. They were offered better accommodation in the high-performance centres than they would ever be likely to find at home. Their diet was enhanced well above the norm – the standard training of an international rower requires consumption of about 6500 calories a day for a man, in the proportion 50 per cent carbohydrates, 30 per cent fats and 20 per cent protein. These amounts were made available in SC Magdeburg, where Jürgen Grobler worked, by two club cooks with no one else to cater for.

Additionally, the scientists searched for any other medical cushion that would enable the bodies they trained to absorb more work without breaking down. In 1962 the East German state pharmacological research and development enterprise, Jenapharm, had isolated an anabolic steroid that it called Oral Turinabol. It was made available for therapeutic use in 1965. Within a year, testing for its effectiveness and for the appropriate dosage for athletes had begun. Once it was approved by the medical team it was made available to the coaches. It was the coaches’ decision, not the medical team’s, to use it to assist athletes. Men and, more controversially, women were dosed in time for the 1968 Olympics in Mexico City.

Oral Turinabol – a synthetic version of testosterone, the hormone that is known to increase muscle mass and bone density – was the ‘little blue pill’ on the breakfast tray of all East Germans training in sports that require either explosive or endurance strength. The athletes had to be seen to take the pill by the coach. The pills could not be taken home or even out of the room because of the secrecy surrounding the whole programme. The pills were described as ‘support’ and the athletes were not told of their content. Indeed, most experiments involved a control group that took a blue placebo.

Güldenpfennig was in the programme and his training intensity would have taken account of the assistance given by the drug. Grobler understood – better than many of his less curious colleagues – what was in the blue pill and will have measured its benefit and reported his findings to the medical commission, run directly by Manfred Ewald, through the Sport Medical Service and its deputy director and chief physician. At the Mexico Olympics in 1968 when Grobler was still studying in Leipzig, testing of competitors for illegal doping was rudimentary and the list of banned substances was short and unsophisticated. Few were discovered to be abusing performance drugs, but the divisions of opinion around the ethical questions posed by their use were becoming clear. The rights and wrongs of this matter were the subject of every coaching and training conference.

Without doubt, the physiological effect of added testosterone and the methodology to establish the most beneficial dose will have been part of the curriculum that Grobler followed. The bulk of the research work at PhD level in the adaptation to sport of therapeutic drugs was carried out in the German College of Physical Culture in Leipzig. There, too, the research studied the damaging side effects and the point at which more damage than benefit was being felt, and when an athlete should be dropped from the programme.

The institute where Grobler was a student was the mothership of the East German sports doping programme, working to orders from the Politbüro. He and his classmates will not have been allowed to graduate without a deep understanding of the development of sports doping at that time. But, unlike almost every other person considering the problem elsewhere in the world, their freedom of expression, and even of thought, was strictly controlled. They had no choice. Even the option of a dignified resignation and exit from their career path was denied. If Grobler or any of his contemporaries had resigned over the state-sponsored doping regime, the quality of life for them and their families would have been compromised deeply and quickly. They could have been convicted and imprisoned for open conflict with the ‘vanguard of the people’ or its representative on earth, the Politbüro. More likely, they would have found that housing and work were denied them.

The authorities’ adverse reaction to a coach or athlete who bucked the system and refused the drugs is the explanation offered by Grobler himself on the few occasions when he has been challenged on his record of compliance with the regime. His mantra has been ‘You have to understand the system at that time. There was no room for disagreement.’

What is rarely admitted – probably because it sounds foolish to readers in a liberal western democracy – is that most of the population of East Germany were part of the collective consciousness expressed as ‘We are the state’. On the opening page of Das Rudern, the detailed rowing textbook published in 1977, the first paragraph ends:

‘The principal objectives of the sport of rowing in the GDR are: 1. The achievement of high performances in competitive rowing for men, women and youths, based on a wide membership, on a comprehensive and systematic basic training, and on a party and class-conscious education of the oarsman into a socialist sports personality.’

The third paragraph ends:

‘In addition, general or specific work in the sport of rowing is carried out in the German College of Physical Culture, in the various Sport Science Committees, in obligatory student sports, in schools, in the National People’s Army, and in the People’s Police, in agreement with the goals of the DRSV.’

These ‘socialist sports personalities’ were all willing and ‘conscious’ members of an elite in East German society that earned its privileges by working harder than anyone else to achieve the aims of the state in beating all contenders. They were the ‘vanguard of the people’ who represented the state abroad.

Already by 1972, only twenty-three years after the state came into existence and in only its second Olympic Games competing as a separate nation, the under-performance of its socialist economy was impossible to hide. For one thing, the Soviet Union had dismantled much of its satellite’s industry. For another, freedom of movement between East and West, difficult since 1945, was blocked completely in 1963 when the already robust frontier to the West was doubled in strength and the walled section through the divided city of Berlin was built. But during this Cold War, television had come to almost every household on both sides of the border, and so East Germans were reminded daily of the gulf in living standards.

In late August 1972 the sun shone on teams arriving in Munich and reflected off the revolutionary acrylic panels in the roof of the main stadium. Everything from the accommodation in the athlete village, to the U-Bahn underground system, to the rowing course at Oberschleißheim – built for the occasion at cost of DM7 million – seemed on the cutting edge of modernist architecture and design. It felt, and was, superior to any Olympic venue in the modern era. It pushed the boundaries of experience in the same way as, it was hoped, the competitions would push the boundaries of human physical achievement.

Into this showcase of expectation and glamour came a drably uniformed rowing team, picked not for their joy in taking part but for their probability of winning medals. There were seven events for men and none for women. A full team comprised twenty-six people, including three coxes. The East German team met the standard it had been set from above by winning a medal in each event. Güldenpfennig won bronze in the single sculls, while Hans-Joachim Böhmer and Hans-Ulrich Schmied also took bronze in the double sculls. East Germany won gold in the coxless pair with the youthful Siegfried Brietzke and Wolfgang Mager, and in the coxed pair with Wolfgang Gunkel and Jörg Lucke, steered by Klaus-Dieter Neubert. They won the coxless fours with arguably their best boat and most reliable medal bet, but lost the coxed fours to the West Germans who had put all their talent into the only boat they could see as a ‘banker’.

In the grand finale, the eights, East Germany’s young rowers, at the outset of their careers, were beaten into bronze-medal position by the reigning European champions New Zealand and by a surprise American crew in a photo finish. East Germany’s tally was three golds, one silver, and three bronzes. The next-best nation on the medal table, the Soviet Union, had two golds in the sculling events but nothing else. West Germany, New Zealand and Czechoslovakia had two medals each, and six nations had one apiece. GBR ranked 14th on the results table. Manfred Ewald and SED secretary Walter Ulbricht should have rejoiced at the result of their directives.

The team and its coaches were rewarded with a cruise to Cuba, the only resort that combined an exotic location with the minimum risk of escape. Even for champion swimmers, Florida was a long way off.

Jürgen Grobler had fulfilled his state-sanctioned quota when Güldenpfennig took a medal at the first international experience for either of them. Both had been outsiders for selection in the winter before, but were now recognised members of the team and would not be dislodged easily. Grobler told Michael Calvin, writing for The Independent in 2012, that ‘I know I cannot run away from my past… some things that were going on at that time might not have been correct, but I can look everybody in the eye and not feel guilty. I am not a doping coach. I am not a chemist.’ That comment might be true superficially but, once deconstructed, it looks disingenuous.

In the winter of 1971–2 Grobler and Güldenpfennig had pushed themselves into the front line of a demonstration of state power focused on winning Olympic medals. In their climb through the ranks they had pushed weaker men aside. The East German team for the 1971 European rowing championships in Copenhagen had seventeen names later selected for Munich.

There was no obligation on Grobler or Güldenpfennig to force their way into the national reckoning. They chose to put their names into the record book. They achieved it by doing the training better than their contemporaries and by embracing the system wilfully and willingly. They knew about the Oral Turinabol and knew its benefits. At no point in his denials has Grobler said, ‘We tried it and found that it did not work.’

When the doping issue became a subject for debate in the 1990s after the collapse of East Germany, Grobler at first said he did not know about it. When that became untenable he said that ‘some things that were going on at that time might not have been correct, but I can look everybody in the eye and not feel guilty.’ It is perfectly conceivable that he does not feel guilty and does not think of himself as ‘a doping coach’ or a ‘chemist’. In the morality of that place and time he did no wrong. The list of drugs that were banned was short and badly defined. There were wide pharmacological roads around most of the bans. When Oral Turinabol was given to athletes it was proven to be extremely stable and in a therapeutic setting it had high safety ratings. It was effective in building lean muscle and bone mass. It was perfect for their purposes and it had two other qualities essential for the East German Olympic programme: it could be matched with epitestosterone to mask the evidence that the extra testosterone was synthetic, and it would be flushed out of the athlete’s body in a short time after the dose was stopped.

However, doping played only a small part in Grobler’s application of the best science flowing from the German College of Physical Culture in Leipzig and elsewhere. The East German team used boats built beside the River Spree in Berlin using a hull profile that was unique at that time. It was designed to have the lowest wetted area – that is, the amount of skin in contact with the water – to reduce the friction or drag. It was designed to pitch and yaw less as the oarsmen moved their weight back and forth on the runners of their sliding seats. It had enough stiffness not to wallow as the weight within it shifted, but was flexible enough to absorb much of the counterforce of rough water to minimise slow-down.

Up to this point, individual boat yards had modified existing designs to seek incremental improvements. They had been subject to fashion but not much hydrological research. The East Germans went about it with legendary thoroughness and seemingly unlimited financial resources. The naval architect who bossed the programme from the start, Klaus Filter, had started rowing at sixteen in Berlin when he began an apprenticeship with the racing-boat builder, Friedrich Pirsch. As his rowing and sculling improved he was steered in the direction of the newly empowered College of Physical Culture in Leipzig ‘to fill his time while in training’. After graduation he went back to work at Pirsch. By the mid-Sixties he was obliged to look for new materials to build the fine shells because East Germany was finding it difficult to import the South American cedars which were then deemed the only material combining strength and flexibility in appropriate measures. The East German state aircraft manufacturer, EFW, had been put out of business in 1961 – probably as a result of Russian interference – and its facilities were made available to the burgeoning sports-equipment research programme.

Filter was able to start experiments with light and strong plastic ‘sandwich’ materials and in his thirties he decided to enhance his boat-building skills by taking a two-year naval architecture course at the university in Rostock. From that he began developing boat designs from first principles. Theoretically they were the fastest built, but they were impossible to row. The means to a solution for the ‘perfect design’ versus ‘practical for humans to row’ was ready-made because rowing as a national sport was already functioning in all its aspects through a committee of the leading coaches, training scientists, experts in biomechanics, medical men, with Filter heading up the technology side with boat designs and materials. Filter says Grobler was, from the beginning, an authoritative voice who understood that collaboration with the other key elements would bring the results the state required.

Biomechanical work with athletes, combined with Filter’s hull dynamics, was crucial in developing the style of rowing which obtained the best out of boats and men. East German crews rowed a long arc by curving the back forwards to enable the arms to reach a long way forward without unduly compressing the legs onto the foot-stretcher that is fixed to the hull. The boat is then levered past the point where the blades are locked into the water. The large flat area of the blade prevents it being torn through the water while the boat is drawn past the lock point by the strength and skill of the oarsman. This rowing style places more strain on the lower back muscles than could be borne by many western oarsmen who trained under a shorter but more intense regime. The East German coaches had full-time professional athletes and so could indulge themselves with long sessions at less intense pressure. They could develop the lower-back strength slowly and carefully over time. The bodies, the style and the boats were each designed for maximum compatibility. Filter, assisted by Grobler, was working to perfect the knowledge of the amount of flex and best hull shape for the boat to match the reaction time of the athletes. If the boat rolls, the rowers must adjust their weight and application of power to match. If the reaction is too slow the roll becomes worse and the boat speed is impaired. The task at which they excelled was to match training to boat shape so as to produce the style of propulsion desired to cover the endurance distance of 2000 metres. It was not a sprint: Grobler and Filter succeeded in developing a type of training that matched athletes and their boats to the distance.

In 1972 Güldenpfennig was given a boat with a plastic laminate hull, finished in soon-to-be-ubiquitous Wehrmacht grey, fitted with a wooden seat and washboards. It was the latest development. Götz Draeger, the man he replaced, had won silver in the European championships in Copenhagen in 1971 in a wooden shell, along with all his teammates. Film of the final in Munich shows Güldenpfennig sculling in the same style as the sweep oarsmen, using his curved back and outstretched arms at the start of the stroke to place the blades in the water as far forward as possible.

The ironies of East Germany’s dominance of Olympic rowing in Munich were many. The original award of the Games to the Bavarian capital by the International Olympic Committee had given immense satisfaction to its president, Avery Brundage. Brundage had risen from poverty on Chicago’s east side to own the largest construction group in the city and to forge a dominant role in US athletics. He had one obsession, which was a hatred of communism and communists, and one closeted dislike, which was for Jews. To hold the Games in a state that shared a long, walled-off border with a communist one must have pleased him.

Munich’s organising committee rose so high to meet the expectations of the Olympic family that hubris was almost certainly heading for a fall. From the start, the Soviet Union and East Germany were winning half as many golds again, with fewer athletes between them, than the United States and West Germany combined. Then on 5 September, early in the second week, came the devastating hostage-taking and murder of thirteen members of the Israeli team by Black September terrorists. The East German rowers were not there to see the shaming of the West German security services in their botched response to the crisis. They had been sent home immediately after their medal ceremonies to avoid western temptations in general and defection in particular.

Brundage, aged 85, who was due to retire as president of the IOC at the end of the Games, spoke at the hugely moving memorial service in the main stadium on the following day. He said that the ‘Games must go on’ and was applauded warmly. But some later revised their opinion after noting Brundage’s deemed hostility to Judaism had been particularly evident in his support for US participation in the Berlin Games of 1936.

The circumstances of Munich’s embarrassment left the East German leadership enjoying a moment of schadenfreude. Although beaten by two scullers, both of whom could be described as idiosyncratic and brilliant, Grobler’s protégé, Güldenpfennig, was a great example of a socialist team ethic. He had only himself to rely on in his races, but he was shaped in the classic East German mould, an interchangeable cog in a bigger machine. He would race the single again in 1973, with the same bronze-medal result, but thereafter he moved into the quadruple-sculls event, introduced to the programme at the 1974 world rowing championships and won by East Germans every year without interruption until 1993.

Jürgen Grobler was hitched to this star and accompanied him, as coach of the quadruple scull, to his first Olympic gold in Montreal in 1976.