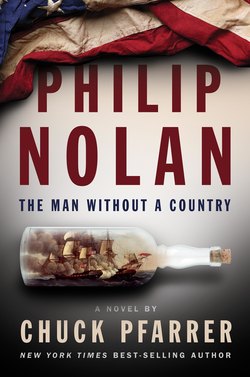

Читать книгу Philip Nolan - Chuck Pfarrer - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеA NOTORIOUS PERSON

HE HAS BEEN ERASED FROM HISTORY. WERE IT NOT FOR A LETTER PUBLISHED in a gentleman’s magazine and a small scrap of newspaper, the world would not know of Philip Nolan at all. Charged with treason, Nolan’s prosecution was irregular, his trial peremptory, and his punishment vindictive. After his court-martial at Richmond in 1807, the records of his birth, his education, his military service, the transcripts pertaining to his indictment and sentence—all were made to disappear. Nolan was then exiled, and it fell to the United States Navy to incarcerate him.

From the first day of Nolan’s confinement until the day of his death, the government made no public mention of him, published nothing relating to his trial or conviction, and allowed no citizen of the United States to inquire about him. The officers and men who held him aboard their ships were honor bound to keep the secret of Nolan’s verdict and the stern conditions of his punishment. They carried out their instructions to the letter.

More than four decades after Nolan’s death, the government that made him vanish allowed an obituary to be published in an obscure portion of the New York Herald:

NOLAN. Died on board the United States corvette Levant, latitude 2° 11' S, longitude 131° 0' W. On the 11th of May. PHILIP CLINTON NOLAN.

Nolan was dead, but every other word was a lie. He had been buried at sea decades before USS Levant ever swam, and the latitude and longitude in the notice of his death are halfway across the globe from the place he’d laid down his life. By the time the Herald’s obituary was printed not one of his family survived to mourn him and almost none of the men who knew him, served with him, or administered his sentence remained alive. Even as they acknowledged his death, the powers that abolished Philip Nolan pushed him deeper into shadow.

There can be no possible harm in telling poor Nolan’s story now. Those of his persecutors who would be disgraced by their treatment of him are, like Nolan himself, long beyond care. It is worthwhile to tell a little bit of Nolan’s life and of his captivity by way of showing what it is to be a man without a country. His story is an obscure bit of history but real enough; presently the reader may judge the facts. And though the tale is grim, it might as well begin on a pleasant spring day.

AN HOUR BEFORE DAWN ON A PALE MORNING—WEDNESDAY, THE 10TH OF JUNE, 1807. In the dark places of the forest locusts chattered, and the air was thick with the cloying scent of honeysuckle. Below the Chimborazo Hill, split rails followed a gravel road to the place where the James River narrowed and turned south. There, the sandy towpath branched past a sawmill and a squat, yellow tavern that was the southernmost habitation of the city of Richmond, Virginia.

Up the dim road, jingling and rattling, came a dray wagon pulled by a pair of sullen mules. Behind the team, a farmer slumped with the reins in one hand; a little boy in a straw hat lounged next to him on the box. Shifting his tobacco, the farmer saw a rider descending the long grade past the tavern. The horse was creditable, a dappled mare of nearly sixteen hands, and seemed to be handled by a gentleman. It was the farmer’s experience that swells abroad at dawn were frequently drunk, and often not riding their mounts as much as being carried by them. The farmer was not inclined to wish the man good morning, for as mount and passenger came on he could see that neither was paying much attention to the road.

As the rider approached, the boy noticed a silk cockade on the side of the man’s round hat, and then, paying attention, he picked out the details of a uniform. A tall, solid frame overflowed the saddle, and long legs in high Hessian boots kept easily in the stirrups. The man was wearing a blue cutaway with red collars, lapels, and cuffs, though in the early dawn the colors were much the same. The soldier’s sword was undone, and its curved scabbard hung from the pommel and coursed indifferently back and forth. For a long moment it was the glory of the uniform that the boy fixed upon—only when the horse drew abreast did he lift his eyes to the rider’s face. Under the round hat was a pair of deeply set gray-blue eyes ruled by fair, even brows; the face was angular, the nose narrow and aquiline, and the man’s jaw was set firmly above a crisp linen collar and neatly tied black stock. Despite an expression of firm purpose the rider seemed distracted, perhaps even fretful.

The boy cleared his throat and piped a bit too loudly, “Good morning, Your Excellency.”

At this, Philip Nolan’s face changed from a blank expression to a look of baffled curiosity. Nolan had hardly registered the oncoming wagon, and were it not for the good sense of his mount he might have ridden them both squarely between the mules. Collecting his reins, Nolan’s eyes searched the boy’s face; in an instant he determined that the officious greeting was not a jab. Nolan smiled, lifted his hat to father and son, and said pleasantly, “Good morning to you, gentlemen.”

They passed on the road, the wagon headed north to market and the waking town, horse and rider heading south to the plank bridge at Bloody Run. The mules capered a bit, and the farmer clucked at them. A mile back, where the river turned, a dozen other gentlemen had come together: men on horses, and men in a fine gilt coach. They had about them an expectant, furtive air, and had it not been for their elegant clothes and fine saddles they might have been mistaken for a gang of highwaymen. As the mules clopped past the yellow tavern, the boy could not help but look back; it was certain the officer was keeping a rendezvous. Father and son knew the infamy of the place where the men were gathered, a barren field marked by a lightning-stripped oak. The clearing was well known, even to local children, as the Bleedin’ Bones. That scrap of bleak, unhappy pasture was the place where Richmond’s gentlemen settled affairs of honor.

IN THE DAYS WHEN OUR REPUBLIC WAS YOUNG, AN OFFICER’S REPUTATION WAS a precious and fragile thing. A careless word, a deliberate bit of incivility, or even one’s choice of associates might give mortal offense. Immutable integrity, an urbanity of manners, and the practice of every commendable virtue were recommended in the finishing of an officer.

Personal honor was the foundation upon which two other great virtues were built: loyalty and duty to country. Philip Nolan’s upbringing, the station of his parents, his pleasant, forthright nature, and native honesty marked him as a person in whom trust and responsibility could safely be placed. His father was a military officer, a respected man; his mother a woman of grace and exquisite manners. Both cared for him and saw that he was given the advantages of an education, the comportment of a gentleman, and a modicum of plain good sense.

After graduation from West Point and a stint as an aide to General Henry Dearborn in Washington City, Philip Nolan was commissioned a second lieutenant of artillery and assigned to duty on the western frontier. Those who knew Nolan as a boy on the frontier, at university, as a cadet, and as an officer esteemed him as a person of determination and great promise. They might also have said that Philip Nolan was as proud as Beelzebub and as stubborn as a tenpenny nail. But these are minor defects in a lieutenant commanding a battery of horse artillery; and for a young officer in that station, pride and fortitude might even be pronounced virtues.

Philip Nolan first met Aaron Burr at Fort Massac on the Ohio River. That log-and-wattle fortress was then the United States’ outermost frontier station and the headquarters of what was styled the “Legion of the West.” The former vice president had arrived at the fort ostensibly on a tour of the Ohio country. He was, in fact, reconnoitering the men who garrisoned America’s western border. The staggering sum of eighteen million francs had recently purchased the Mississippi watershed from Emperor Napoleon Bonaparte. The transaction had nearly doubled the landmass of the United States, but left the young American republic and the Empire of Spain to carp over the boundaries of an almost infinite wilderness.

After a staunchly patriotic banquet given in his honor, Aaron Burr sought a private word with Nolan. Burr made a point of learning about the persons who could be of use to him, and he’d made a careful study of Nolan. The young officer’s aptitude for languages, his ability with maps, and above all his family connexions made him an asset to be cultivated. Recently graduated from West Point, Nolan was the only trained artillerist and cartographer at the fort. Burr flattered him by saying he had seen several of Nolan’s maps at Washington City; why, in fact, he had one just at hand. Nolan bowed, and the small, keen, dapper little man rolled out a map of the Orleans Territory.

“I dare say you know this country, Mister Nolan, and the land west of the Sabine?”

“Well enough, sir.” Nolan answered, “My mother had a porcione.” He put four fingers on the map. “Here, near to Puebla Magda. I spent most of my boyhood there.”

“Texas,” Burr said, “should be a republic.”

“The King of Spain would disagree with you, sir.”

“Damn the King of Spain, Mister Nolan. I mean to take Texas from the Spanish.”

Nolan was astounded. He had his own reasons to want to burn powder against the Spanish; Philip’s brother, Stephen, had been shot by a troop of Mexican cavalry after leading a party of settlers across the Brazos. The death of Nolan’s older brother had driven his mother to drink and shattered their family. It was these heart wounds that had turned Nolan from a rambunctious little boy into a soldier. Burr knew this as well.

“The purchase of the Louisiana territories has expanded the nation,” Burr continued. “But Mister Jefferson has made a bargain with the devil. The wars that convulse Europe show that Napoleon can never keep his word. His treaties are worthless, and if Jefferson were to send him all the dollars in the world, it would do nothing to secure the lands the French tyrant has pretended to sell to us.”

Burr looked directly into Nolan’s eyes. “The Spanish are now the allies of the French. Should Napoleon decide to snatch back what he has sold to Mister Jefferson, it is the dons who will do the taking. The Spanish are already moving troops from Monterrey and Mexico City.”

“Then they should be kept away,” said Nolan. “Driven across the Rio Grande if necessary.”

The little man smiled. “You have grasped the matter perfectly.”

Burr told Nolan that two nations could not share the destiny of a single continent, and that Texas and the lands all the way to the Pacific were the legacy of the United States alone. No one spoke the word “treason.” The old politician was too crafty, and Nolan’s simple patriotism was too well rooted. Burr’s scheme was to start a war with Spain and then seize the territory west of the Mississippi. The plot was no idle daydream. Burr had raised tens of thousands of dollars, purchased rifles, cannon, and powder, and commissioned a flotilla of riverboats. Burr had private discussions with the military and political leaders of America’s frontier, obtaining their acquiescence, if not their publicly declared support. Andrew Jackson, the future president, and Major General James Wilkinson, commander of the United States Army, were among Burr’s intimates. The ex–vice president had a genius for manipulation, and he knew exactly where to press the young lieutenant. Burr had ready cash—he could pay for a thousand soldiers—but he needed officers, men of honor, to lead them. Burr asked Nolan to join his venture; glory awaited, the deceiver whispered. All it required was men with pluck.

Nolan’s consideration of this fatal offer was all too brief. He reflected on the object of Burr’s scheme rather than the means by which it should be accomplished. Nolan did not appreciate that others, besides Spain, might object to what was, in fact, an unlawful and unjustifiable use of force—a filibuster. What Burr proposed was a military adventure, and Nolan saw in it not only a place for himself, but vindication for a brother he had loved.

Burr dictated a pair of letters, which Nolan dutifully copied down. These were then transcribed into a hieroglyphic-like cipher that Burr produced from a slim iron box. The letters dealt chiefly with the movements of men and materiel. There was some political language as well, but truth be told, the encryption process proved so laborious that eventually Nolan merely assembled words and did not pay strict attention to what they entailed.

Working through a long night, Nolan made fair copies and in the morning submitted them to Burr for review. They were pronounced accurate, and Nolan was delighted to be charged with delivering them to General James Wilkinson, the military governor of the Orleans Territory. The grand design, it seemed, was coming to life. Burr arranged a leave with Nolan’s commanding officer and made sure he was well provisioned. Carrying Burr’s dispatches, Nolan rode south from Fort Massac to the Orleans Territory, and into the noose of doom.

On the day of Nolan’s arrival, the wily general received him kindly and accepted the letters. In a show of military courtesy, Nolan put himself at the general’s service and was shown to a tent within the confines of Wilkinson’s headquarters. That night, exhausted from his seven-hundred-mile journey, Nolan fell asleep, convinced that his future was about to blossom.

Though he had been an early and enthusiastic supporter of Burr’s plot, General Wilkinson was a calculating man. Unknown to his superiors in Washington and unsuspected by Burr or his brother officers, Wilkinson was in secret correspondence with the viceroy of Mexico. In this mercenary, treacherous arrangement, Wilkinson was known to the Spanish as Agent 13. Burr had no inkling, and Nolan had no idea at all, that they were dealing with a dyed-in-the-wool traitor.

Perhaps the old general had heard the rumors that revealed him as Burr’s principal co-conspirator; perhaps he had been ordered by his Spanish paymasters to thwart Burr’s plot. Whatever the reasons, General Wilkinson found it in his interest to suddenly denounce Aaron Burr, repudiate their previous agreements, and renege on his promise to add the battalions in his command to an attack on Mexico.

Wilkinson had changed sides. He now had to cover his tracks.

At dawn Nolan was arrested in his tent by Wilkinson’s adjutant. He was taken again to headquarters, and there found the general a changed man. Sitting behind a field desk, Wilkinson’s broad bottom was propped on a saddle put down upon a milking stool. The general pointedly asked if Nolan had been granted permission to leave his post at Fort Massac.

“Verbal permission, sir.”

“Then you can show me no orders?”

In a corner, Nolan caught sight of a clerk dipping his pen and rapidly scribbling. “Respectfully, sir, if I have deserted, I have done so in uniform, and fled to the headquarters of my commanding general.”

The great bulk was unmoved. “I understand you have been in contact with His Excellency Colonel Burr?” Wilkinson huffed.

“I have, sir. He asked me to carry to you the letter you have at hand.”

In the corner, the scratching stopped and the clerk looked up. Wilkinson’s eyes narrowed. “What else did Colonel Burr say to you, Lieutenant Nolan?”

“I was offered a place in his expedition, sir. I heartily accepted it.”

Wilkinson smirked like a mandarin. “You are dismissed,” he wheezed.

The adjutant said sternly, “Consider yourself confined to post.”

It seemed at first to be some sort of prank. The next day a dragoon guard escorted Nolan south to Fort St. John and confined him in a casemate. Nolan was certain that when Burr arrived in New Orleans the matter would be resolved. It only added to his bewilderment when a guard told him that Aaron Burr was now a fugitive with a federal price on his head. A scrap of newspaper shoved though the bars of his cell confirmed it.

A week passed. Then, with great fanfare, General Wilkinson announced that he had “intercepted” a coded letter revealing a diabolical plot to dismember the Union. Nolan’s heart sank. There could be only one such letter—and Philip Nolan had placed it into General Wilkinson’s fat, moist hand.

Wilkinson declared martial law in the city of New Orleans and his provost marshals rounded up dozens of potential conspirators, including members of the local militia, political rivals, and several of the general’s creditors. In the renaissance of his patriotism General Wilkinson found traitors everywhere, except in the mirror. By the end of November, Nolan found himself under close arrest and marching north to Washington City with a dozen other officers and civilian officials. After more than a month on the road, prisoners and escort were met by a United States marshal, transferred from military into federal custody, and diverted to Richmond.

In an icy rain the escort drove the prisoners on past Staunton, through Rock-fish Gap, and down the long Three Notch’d Road past Charlottesville and under the frowning brow of Monticello itself.

Arriving at last in Richmond, Nolan was placed in the city gaol with a colonel and a major, both formerly members of General Wilkinson’s staff. During the long march from New Orleans neither officer had shown Nolan much courtesy. Soon after they were lodged in the Richmond gaol, these officers were paroled almost at once. For reasons not explained, Nolan was turned out with them. On a blustery morning, the officers left Nolan standing in front of the hoosegow with his baggage and saddle piled at his feet. As it began to rain, Nolan’s cellmates climbed aboard a carriage provided by the Richmond Federalist Club. They did not say so much as adieu.

Nolan felt anger rising, the mailed fist of self-pity, and for the first time since his troubles began he considered tossing off his uniform, saddling a horse, and riding away. That he did not abscond said more about Nolan’s doggedness than his sense of duty.

With his last few dollars he took a room at the St. Charles Hotel. Nolan found it a pleasant if somewhat noisy place, and not many of the lodgers seemed to care that he was still, technically, a federal prisoner. From the St. Charles, Nolan wrote confident letters to friends and a less hopeful one to his mother, gone long ago to Vera Cruz. In each, he told the story of how he had come to be arrested. Nolan could state honestly that he did not fully know the contents of Burr’s letter, but he understood that it dealt with some sort of military combination against the Spanish. Nolan thought sincerely that any such grand machination must have been approved by President Jefferson. In this he was flatly and fatally mistaken.

Two weeks after his arrival in Richmond, Nolan was joined by Wendell Fitzgerald, a friend from university and West Point. Fitzgerald had bravely acceded to Nolan’s request to serve as his attorney, and he sweetened their reunion by escorting his wife, Alden, and her cousin Lorina Rutledge to Richmond. As spring came to the Tidewater, Fitzgerald went back and forth to the House of Delegates, collecting the particulars of Nolan’s alleged crimes, copying depositions, and conferring with the prosecutors.

Nolan had ample time to escort Mrs. Fitzgerald and Miss Rutledge about Richmond. The three were often seen about town, and more was known and said about the young officer than he could have imagined. The talk led to an unfortunate incident on Grace Street. As Nolan was passing by with Miss Rutledge, a local nabob, Randolph Creel Bell, an inbred, ill-mannered minor scion of several of the First Families, sniffed, “There goes dessert, arm and arm with disgrace.”

Nolan was inclined to let the remark pass, and had he been alone he would have, but as he was escorting Miss Rutledge he was bound to ask the man for an explanation.

There was a short, escalating exchange, and Colonel Bell, as he styled himself (he held militia rank), refused either to withdraw his comment or to clarify it. As Alden and Lorina looked on, Nolan slapped the beaver hat off the colonel’s lump-shaped head. It tumbled into the mud and Nolan crushed its crown under the heel of his boot. “My name is Philip Nolan, sir. And should you choose to resent this, I may be found any morning at the St. Charles Hotel.”

The colonel had no choice but to resent it, for there was no affront more serious than a blow. Notes were exchanged and satisfaction was demanded.

Wendell Fitzgerald first declined to serve as a second, and did so only after Nolan pointed out that should he allow the affront to pass, Bell would post him as a coward, rascal, and poltroon. Such dishonor would unquestionably prejudice his case.

Fitzgerald understood that Nolan would be tried not by expedient men, citizens, or politicians, but by fellow officers. For them all, the notion of personal honor was placed on the same pedestal as duty and love of country. Nolan had no choice but to meet Bell on the field.

On the morning of his interview with Colonel Bell, Nolan rose early, breakfasted alone, and wrote a note to Lorina Rutledge. His were plain soldier’s words, and the possibility that they might be his last gave a certain grace to his composition. He told Lorina that he regretted that she had been exposed to unpleasantness on his account, but he found it both a pleasure and an honor to discharge his duties as a gentleman. Nolan slipped the letter under the door of the house she shared with the Fitzgeralds and rode south under a humpbacked moon.

The stars were fading by the time Nolan crossed the plank bridge at Bloody Run. As he turned his mare into the clearing, the wheel marks of Colonel Bell’s carriage were still plain in the dew. Nolan might have been excused a flush of excitement or even fear, but he had previously been a party to several affairs of honor, as both a principal and a second. This morning, to his own surprise, he felt nothing beyond a dull sort of annoyance.

Bell’s carriage was parked beneath a dogwood tree, and several horses were tied to its rear wheels. With the most exacting courtesy, Nolan touched his hat as he rode past. The colonel chose rather dramatically to look away, and his several friends stopped their murmuring and followed Nolan with hard eyes. Bell kept his gaze scrupulously elsewhere, but Nolan, who had no impression to make, studied the colonel for several seconds.

Randolph Creel Bell was Nolan’s senior by at least twenty years. He was dressed in a silk waistcoat and breeches, and the thought occurred that the colonel did not wear his uniform because it could no longer be pulled across his preposterous belly. Nolan and his adversary presented two perfect opposites. Bell was visibly distracted, and Nolan calmly indifferent—but, in truth, neither man had wished the incident to go this far.

Bell had considered Nolan’s situation and projected on it his own arithmetic. He figured that Nolan could gain nothing by fighting a duel while facing a court-martial; win or lose, a duel would adversely affect his case, especially by taking the field against a nominally superior officer. Bell had expected Nolan to do the most expedient thing: endure the affront, decline the meeting, and preserve his life. Bell’s original insult had been thus calculated, and he had truly thought he could make a joke at Nolan’s expense—and make it stick.

For his part, Nolan still expected Bell to render an apology; perhaps one would come. Nolan had made inquiries, and his opponent’s reputation was not that of a fighting man. The present Colonel Bell, long ago a captain, had been attached to the staff of Revolutionary General Horatio Gates. Bell, along with his notorious principal, was at the Revolutionary War Battle of Camden, the most ignominious defeat of American arms in history. In the midst of that fight Bell had been assigned to carry a dispatch to General Baron De Kalb, then commanding the American right. Quailing behind a stone wall, Bell watched as De Kalb was shot down when the British flanked and then overwhelmed that position. In the face of a British bayonet charge, young Captain Bell consulted his own safety and was one of the first officers to bolt down the Camden Pike. As the American line collapsed, Bell rode north. Fleeing the disaster, commandeering post horses at gunpoint, Bell had outflown even the craven General Gates himself, arriving in Charlotte, sixty miles away, before dusk.

Bell’s account of his conduct at Camden improved the farther he was from the field. And though he did his best to recast himself as a hero, he was considered by his betters to be nothing more than a skedaddler and blowhard. Bell never again saw combat, and his appointment to Thomas Jefferson’s staff and a vacant colonelcy in the Virginia militia was due to a finely honed talent for self-preservation and the obsequious cultivation of an uncle in the Continental Congress.

Confident that Bell would apologize rather than face him in a duel of arms, Nolan rode to the far end of the clearing and dismounted, hanging his hat on the pommel of his saddle. Wendell Fitzgerald stepped forward to take the bridle. A head taller than his friend, Fitzgerald was a bear of man, nearly as broad as Bell but immeasurably stouter of heart. Nolan glanced around; on his side of the clearing there was only Fitzgerald. He had no other seconds or partisans.

“You seem to have sauntered down,” Fitzgerald said.

Nolan glanced at a blanket draped over a tree stump—on it were a set of pistols in a box. “Pistols for two and coffee for one.”

Fitzgerald said nothing. He was not a glib man and did not care much for dueling.

“Bell seems disappointed I have kept my appointment.”

“You both may be disappointed.” Fitzgerald picketed Nolan’s mare next to his own. He said quietly, “Where is our friend Doctor Kosinski?”

“He sends his best compliments but does not wish to come,” Nolan said. “He told me that dueling is for imbeciles and advised me to skip breakfast in the event I am shot in the belly.”

“That was sound advice.” Fitzgerald glanced at Bell’s crowd of seconds, one of whom was an old-fashioned gentleman in a grizzled physician’s wig.

“Perhaps we’ll not have need of a surgeon,” Nolan said. “I don’t think this man will fight.”

“You are ever hopeful, friend.” As Fitzgerald walked toward the carriage, Bell’s chief second, a judge named Macon, came purposely forward.

“Good morning, sir.”

Macon did not answer.

“On behalf of my principal, I ask again if bloodshed might be avoided and a misunderstanding put to rest.”

“If there is a misunderstanding, Mister Fitzgerald, your friend is responsible for it,” Macon wheezed. “Colonel Bell stands ready to accept a full and complete explanation.”

Nolan removed his jacket and placed it over the picket line. Rolling up his sleeves, he walked into the meadow next to Fitzgerald. “I would be pleased to offer my compliments to Colonel Bell,” Nolan said, “but I am afraid he has underestimated my regard for the lady in question.”

“No offense was intended to your female acquaintance,” Macon answered.

“She is more than an acquaintance, sir. On that afternoon she was under my protection. And as much as it pains me to discomfort the colonel, I expect an apology.”

Bell snorted and for the first time walked forward. “I am obligated to explain myself only to a gentleman.”

Fitzgerald said patiently, “A misunderstanding is—”

Bell was agitated and interrupted: “There is no misunderstanding. Philip Nolan is an accomplice of Aaron Burr, and a damnable traitor.”

“Of the first accusation, sir, I readily admit to being acquainted with Colonel Burr. But I am no traitor.”

“You are a damned liar, sir. And a bastard.”

Fitzgerald saw the plain, inimical expression on Judge Macon’s face and the pinched, disgusted attitudes of the men standing by the carriage. There had indeed been more said about Philip Nolan behind his back than to his face. Some of the gossip was merely that, tattletale and innuendo, but some of it was fact.

Bell now mentioned some of the embarrassing circumstances surrounding Nolan’s birth, and spoke with frank disgust about an infamous liaison between Philip’s mother and the British general Sir Henry Clinton during the occupation of Newport in the Revolutionary War. Rising in his own indignation, Bell affirmed Nolan to be not only the miserable by-blow of a skulking British lord, but a traitor sprung from a long line of unchaste, vexatious, and loud-mouthed slatterns. In the face of this harangue Nolan stood rigidly, humiliated and speechless.

It was only Fitzgerald’s parade-ground voice that overcame Bell’s yammering. He barked, “Enough, sir. That is enough.” It was, in fact, more than enough. Shaking with rage, Nolan turned toward the stump and snatched up one of the pistols. The move was so deft and furious that Fitzgerald saw fit to place himself between Nolan and Bell. “Steady, Philip,” Fitzgerald said. “Steady.”

When Nolan had taken possession of the weapon, there had been a flurry among Bell’s partisans. There were half a dozen, and all were armed, except the physician. Should it come to a general engagement (and such things happened in the South), Fitzgerald and Nolan would be at a singular disadvantage.

Fitzgerald was embarrassed for his friend, but he kept rigidly to the protocol of the matter at hand. Fitzgerald turned to Macon. “I assume that we are at an impasse?”

There was a moment of silence. Every man present knew this business must now come to blood. There was no way for Bell to climb down, and as Macon seemed unable to find his tongue, the colonel tried for something poetical. Bell rumbled, “I care more for my honor, and the glory of my country, than I do for my life.”

Nolan stifled a guffaw. “You pompous jackass. You can polish a saddle—now let’s see how you shoot.”

A second pistol box was opened, and Bell took up a weapon. He made a brief show of examining the lock and mechanism and walked about the field aiming it here and there and checking the light. He eventually had a flunky go to the carriage and retrieve his spectacles. He put them on and walked to the spot where Nolan and Fitzgerald waited. The two principals faced each other and the seconds withdrew. Fitzgerald pulled a handkerchief from his waistcoat, and Bell and Nolan turned their backs.

Fitzgerald said, “You may ready your pieces.”

The locks snicked back, and Fitzgerald noticed that although Nolan’s expression was firm, even malicious, his hand trembled as the pistol cocked.

“Gentlemen, the distance is ten paces. Upon my signals, you may turn and then fire.”

A horse stamped and blew.

“Colonel Bell, are you ready?”

“Ready.”

“Lieutenant Nolan, are you ready?”

“I am, sir.”

“Vous pouvez commencer le marche,” Fitzgerald said. The men stepped out in long soldier’s strides. Fitzgerald lifted the handkerchief to his shoulder. Eight steps. Nine steps. Ten steps.

“Présent!”

Bell lumbered about to find Nolan already facing him, weapon leveled. They stood opposite each other for several seconds while Fitzgerald held the kerchief aloft. Finally Fitzgerald said, “Allez,” and the handkerchief floated to the grass.

Almost at once there was a snap and flash in the pan of Nolan’s weapon. The noise was not loud, only a crack and hiss; it was immediately apparent that Nolan’s pistol had been half cocked and had not discharged. All agreed that this much happened.

The accounts from this point diverged greatly. Nine men were present in the meadow, including the duelists themselves. Five of the witnesses were sworn partisans of Colonel Bell, and only Fitzgerald would ever repeat a version of events that favored Philip Nolan. Bell’s surgeon, Doctor Van Sutter, forever after claimed neutrality, insisting he was not in a position to witness the action or to even to comment as he was not familiar with the code duello.

When the final command was given, Fitzgerald saw plainly that the muzzle of Nolan’s pistol was pointed down and away from Colonel Bell. Though his weapon had misfired, Fitzgerald firmly believed that Nolan had intended to throw away his shot. Even Macon saw that Nolan’s hand was no higher than his waist and his wrist was turned out and away from Bell. Nolan had been first to pull a trigger, but even if the weapon had functioned, the ball would have thumped harmlessly into the ground.

Bell’s supporters claimed that the two men fired “almost instantaneously.” In reality, several seconds passed between the moment Nolan threw away his shot and Colonel Bell aimed and fired. On the field that morning, those several seconds unfolded like a parade of seasons; it was enough time for minds to shape thoughts, for heads to turn, and for words to form. And it was time enough for Colonel Bell to aim deliberately, squeeze the trigger, and hit Nolan squarely.

The ball struck Nolan six inches under the left clavicle, tearing open his shirt and knocking him onto his back. The wound was thought to have killed him instantly. On the ground, Nolan remained motionless for the several seconds it took Fitzgerald to reach him. From the other part of the clearing, Bell yelped with pleasure and there were shouts and halloos from his supporters.

Nolan did not utter a sound, but eventually pulled up his legs and rolled onto his side. The meadow was completely silent; even the locusts and birds were still as Nolan came first to his hands and knees and then, reeling, to his feet. Frothy pink fluid pumped from the wound as he shook off Fitzgerald’s help.

“I can stand,” Nolan choked. His eyes were like an animal’s.

Bell was huddled with his seconds. Nolan said hoarsely, “I shall have a second pistol, Mister Fitzgerald.” Nolan swayed on his feet, and it looked like he would fall any second.

Bell said, “The affair is ended.”

“It is not, sir.” Nolan’s face was ashen. “Two passes must be made before a resolution.”

“Both parties have fired,” Macon said to Fitzgerald. It was not mere hairsplitting. Nolan had pulled the trigger, and neither the accident of his misfire nor his intent to throw away his shot disqualified his actions.

“I am accorded two passes by custom,” Nolan panted.

“He is in no condition to continue,” Macon sniffed. “Look at him.”

Nolan bellowed, “Damn you for a coward, sir. Arm that quim friend of yours or I shall fight you next.”

Fitzgerald handed Nolan his second pistol. The code did undeniably call for two passes should either principal demand it.

“Colonel Bell, prepare to receive Lieutenant Nolan’s second volley.”

Bell considered the situation. Though Nolan looked like he might use his pistol instantly, the colonel did not consider Fitzgerald and a raving, wounded maniac a match for six of his friends. Bell’s expression changed when he surveyed the men standing by his carriage. They were solemn and unanimous in their opinion that the affair was not finished.

“Colonel Bell,” Fitzgerald barked, “arm yourself.”

“You are not serious,” Bell sputtered. “This matter is concluded. I am satisfied.”

“I am not,” wheezed Nolan. Blood dripped from his shirt and blotted his trousers.

“Judge Macon, do something.”

“Two passes are stipulated, Colonel,” Macon said firmly. “It is what honor requires.”

Fitzgerald said, “We are in earnest, sir. Return to the field.”

Bell took a step backward, and Fitzgerald lifted his saber. “Stand your ground, sir, or by God I will strike you down.”

“Fitzgerald, for Christ’s sake, stop this farce,” Bell stammered. “Goddamn it, Nolan. Our affair is settled.”

“It is not, you sack of shit,” Nolan rasped. Using both hands, he managed to pull back the hammer of his pistol.

Macon came slowly forward and pressed a second pistol into Bell’s hand.

“Ready your weapon, Colonel Bell,” Fitzgerald intoned. He used his sword point to lift the handkerchief from the grass, and Bell hurriedly snapped back the hammer of his weapon.

“This is insane,” Bell spit. “It is simple murder.”

“Gentlemen, to your places,” said Fitzgerald.

At the other end of the field Macon whispered something to Bell, then walked slowly back toward the carriage, obviously taking his time. Bell narrowed his eyes at his adversary; Nolan presented an unsteady, perhaps even defenseless target—he had yet to raise his pistol. Bell turned smoothly sideways, placed his feet with deliberation, lifted his weapon, and aimed exactly at the livid stain on Nolan’s shirt.

Panting, unsteady on his feet, Nolan’s world had become a constricting circle of agony. He could see Bell only through a wavering blur of pain.

“Colonel Bell, are you ready?”

“I am.”

There was a banshee’s howl in Nolan’s ears.

“Lieutenant Nolan, are you ready?”

Struggling to lift his pistol, Nolan did not answer.

“Mister Nolan?” Fitzgerald repeated.

“Yes, goddamn it,” he grunted. “Finish it.”

Fitzgerald lifted the kerchief. “Présent.”

Nolan saw Fitzgerald’s lips move, and in a strange elongation of time he watched the handkerchief flutter toward the ground. He never heard the command to fire. There were simultaneous flashes of orange light, and gun smoke roiled across the meadow. Bell’s shot trilled past Nolan’s ear and went away through the trees, cracking at twigs and bark. Nolan’s ball traveled flat and straight, struck Bell above his right eye, and blew off the top of his head.

Nolan staggered backward, and the pistol dropped from his hand. Folded by heaving agony, he toppled onto the seat of his pants. As pain closed its fists around him, blood pooled under Nolan’s tongue in thick, salty mouthfuls. Arms crossed and legs drawn up, Nolan rolled onto his side and a low groan rumbled in his throat.

Fitzgerald knelt and bundled him into his arms. Light was coming over the trees now, and it seemed suddenly and unbearably bright. Across the meadow, one of Bell’s men placed a cape over the colonel’s shattered, lopsided face. Oddly, his spectacles were still perched on the end of his nose.

Nolan coughed and felt his body going strangely numb. Fitzgerald held his friend, horrified to see blood pooling in the dirt beneath them.

Nolan whispered, “Hold me, Fitz. Hold me. Now I am surely killed.”