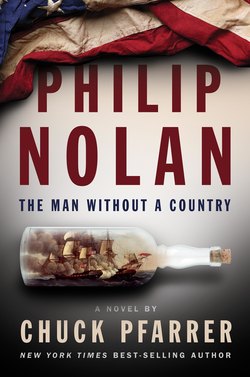

Читать книгу Philip Nolan - Chuck Pfarrer - Страница 14

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеGOING ABOARD

ENTERPRISE’S BLUE CUTTER WAS COXED BY A PETTY OFFICER, A BLUFF SAILOR with red muttonchop whiskers. Curran could hear the coxswain and stroke oar joking together as the boat approached. They were dressed in their best shore-going rigs: blue jackets, duck trousers, kerchiefs, and tarpaulin emboldened with the words “United States Frigate Enterprise.” All were happy, obviously expecting liberty.

“Coxswain, we are for Enterprise,” said Curran as bow oar heaved a line to the pier.

The sailor at the tiller, Finch, looked at Curran and then at the prisoner and was made instantly solemn. In the cutter the smiles were gone and a dozen oarsmen sat with their heads locked, looking neither right nor left, but exactly at nothing, eyes in the boat. For a few seconds no one spoke or moved a muscle.

“You, sir, in the boat. Do you hear me?”

“Yes, sir,” Finch said. “We’re here to get you.”

Curran’s things were quickly put aboard. The coxswain narrowed his eyes at the man in the blue coat, troubled by the chains and shackles draping from his hands. “Sir, would you like me to send out for them leathernecks? We got nothing for arms aboard except a pair of cutlass.”

“That won’t be necessary,” Curran said as he dropped into the cutter’s stern. “Directly to the ship, please.” Curran sat on his sea chest next to the coxswain, and the prisoner was put forward in the bows.

“The ship it is, sir.”

The cutter backed water, came smartly about, larboard holding and starboard pulling, and the men stretched out for the ship. There was only the sound of the trucks in the oarlocks and the smooth pull of water under the sweeps. Curran noticed that the oarsmen on either side of the prisoner took pains to lean away from him as they plied their oars.

In the boat, the man in the blue coat did his best to become invisible. The prisoner had such a talent for silence and self-effacement that Curran soon forgot he was there. For the ninth time in twenty minutes Curran made sure that his papers and orders were in their silk and sailcloth folder, checked again that his number one scraper was firmly lodged on his head, and flicked away a bit of lint from the shoulder of his best dress blue jacket.

Ahead of him, still most of a mile off, Curran could see Enterprise riding easily. She had shifted colors and now wore the jack at her bow and the national ensign astern. Curran had so concentrated on the American ships he’d almost failed to notice that the harbor was full of vessels, merchants all of them: Swedes and Danes, Finns and Dutchmen, and lateen rigs of the Med, all in various states of cleanliness and repair. Small boats plied between them and ranged up and down the harbor. There were even a few stranger craft—herring busses, xebecs, and a dismasted hulk being used as a receiving ship. Most shocking of all, a hermaphrodite-rigged poleacre, painted red, black, and white with a lateen sail rigged as a mizzen, a contraption so heterogeneous that it could only have been sailed by men without a notion of shame: Ragusians or perhaps Greek spongers.

As the cutter came into the anchorage, Curran could see that Enterprise was busy. Constellation had come and gone in silence, but from Enterprise came the screech of a bo’sun’s pipe and orders shouted from deck to maintop. Enterprise was putting over her long boat and both gig and cutters, liberty men in some, working and watering parties in others. Bumboats from the town were already about, offering every temptation of the port, jabbering in the pidgin of half a dozen languages, and deals were being struck for many things more potent and desirable than bottles of blackstrap and mitad y mitad.

Close up, Curran had seen Enterprise only in the yards at Boston. The ship had seemed impressive then, but from the stern sheets of a 30-foot cutter the frigate seemed so massive and rooted in the water that it did not float so much as jut up from the sea like a cliff. As the cutter pitched in the chop, the tall black sides of the frigate did not move, but conducted the swell down the waterline, showing a band of white and copper as the waves passed. Enterprise was renowned, as was her sister Constitution, for stiffness in a seaway. She was nearly 210 feet from beakhead to taffrail, 2,200 tons burthen, and of course ship-rigged. Enterprise was what the British had come to call a “pocket ship of the line,” for they learned that Enterprise and her sisters outgunned and outsailed most of what His Majesty’s navy called frigates.

This Enterprise was the fourth United States warship to bear the name. Laid down at the Boston Navy Yard in 1811, “Easy E” had an enviable reputation as a comfortable ship and was as fast as any man o’war that ever swam. Built from a Humphrey draft, Enterprise differed from Constitution in that she had a taller rig, an enclosed spar deck (and therefore an elevated poop), and a pair of stern galleries instead of only one. Her masts were raked aggressively, and her bristling rows of gun ports and Nelson chequer gave her a menacing, even predatory appearance. All of this imparted on Curran a sudden sense of wonder, of both the ship and his new place on it, and he was conscious not to stare at the rigging and to make sure his mouth was closed lest someone aboard mark him as a gaper.

Above them from the quarterdeck came the hail, “Ahoy the boat,” to which Finch boomed out, “Aye, aye,” meaning that there was a commissioned officer aboard the cutter. Curran did not suppress a grin. This was the first time in his life he’d been the object of this small bit of naval courtesy. Finch returned the nod of the officer of the deck, and the cutter passed under Enterprise’s towering stern. Curran tucked his orders into his jacket, hitched up his sword and scabbard, and stepped past the prisoner toward the bow of the boat. The painter was tossed to a ship’s boy, and the cutter made out to a boom on the larboard side of the ship.

Aware of the eyes upon him from the decks and the rigging, Curran started up the side. Halfway up he remembered the pistol in his waist, made it secure, and came through the entry port onto the quarterdeck. On deck his arrival generated no ceremony. Men passed fore and aft, rolling out hogsheads for the ship’s fresh water, mending and splicing, and removing the battens and hatch covers from the hold under the foremast. A lieutenant about Curran’s own age had a long glass tucked under his arm, the emblem and principal instrument of the officer of the deck.

A short, tousle-headed midshipman sat on the ladder of the main companion-way, glancing around generally and then staring at Curran openly. Curran turned aft, touched his hat to the colors, and then faced the officer of the deck. “Permission to come aboard, sir?”

“Granted. Come aboard.”

The smells of the ship were familiar—tar, turpentine, paint, sweat, and galley smoke. “My name is Curran, sir, reporting aboard from Epevier.”

A smile now, the first one Curran had seen all afternoon, and the officer of the deck held out a tanned, callused hand. “Welcome aboard, Mister Curran. My name is Kerr.”

Down from the quarterdeck came a large, broad-shouldered man wearing a short blue coat and duck trousers. Kerr put his heels together and touched his hat. “Good morning, sir.” Curran at once guessed this man to be the ship’s executive officer, and a taut one despite his working clothes. Curran saluted, though the man in the stained jacket was not covered.

Kerr said, “Mister Erskine, may I present Lieutenant Curran, just reported . . .” Kerr faltered on the foreign word, and Curran quickly covered, “Reporting transferred from Epevier, sir.”

“Excellent, Mister Curran. We have been expecting you. I’m Erskine, the exec.” Obviously a man who trusted his own work, Erskine carried a marlinspike in his belt. He bellowed an order to a pair of sailors working in the mizzen top; at that same moment, a rooster in the coops at the waist chose to crow at the top of its lungs, and a group of caulkers forward started a fine, syncopated hammering.

“Sir,” Curran shouted over the din, “I have dispatches for the squadron and mail for the ship.”

The word “mail,” a single syllable muttered on the quarterdeck, was able to penetrate through the clangor and passed quickly with smiles and winks from maintop to the cable tier.

“Mail, did you say? Well then, sir, you are welcome indeed.”

The mail and dispatches were brought up from the cutter, and the canvas sacks were at once taken up by the captain’s clerk and a smiling group of sailors. Erskine then noticed the pistol tucked into Curran’s waist.

“Was there some excitement ashore, Mister Curran?”

“No sir, I shipped this to guard the prisoner from Constellation.”

Kerr mumbled a remark about every man aboard Constellation being a villain, or at least a degenerate, for there was a great rivalry and even antagonism between the ships. One of Enterprise’s old salts sauntered to the rail and looked down into the cutter.

“It’s Plain Buttons, sir,” said Padeen Hoyle, senior petty officer in the starboard watch, “still on his cruise of the world.”

Erskine looked over the rail and said softly, “Poor bastard,” and then turned to Curran. “Do you have the prisoner’s instructions?”

Curran touched his jacket. “Here, sir.” The leather envelope was next to his own precious certificates and orders.

“Mister Kerr, see that Mister Curran’s things are brought aboard directly,” Erskine said. “Midshipman Wainwright will show you to the wardroom.”

When Mister Midshipman Wainwright did not appear instantly, Erskine barked, “Wainwright, goddamn your eyes, you idle lollygagger . . .”

The midshipman sprang like a cat from the hatchway and bounded over to the larboard quarterdeck. He was a thin little boy, almost swallowed up by his round hat. “Here I am, sir.”

Erskine’s eyes were hooded. “Mister Wainwright, I hope you are not unaccommodated. Are you at leisure, sir? Available for an assignment?”

Wainwright blinked as if he were peering into the mouth of a carronade. “Oh yes, sir. I am quite available, sir.”

“Then you will please show Mister Curran below and see that his things are placed in his cabin.” Erskine said these words as though he were speaking to a particularly intelligent but untrustworthy monkey. The exec’s smile returned when he said, “We’ll give you some time to settle aboard, Mister Curran. At four bells, please be so kind as to present yourself to Captain Pelles.”

“Yes, sir. Thank you.”

Wainwright stepped forward, touching his hat again and again. “Good afternoon, sir, welcome aboard, sir, and this way, sir, if you please.”

Kerr rolled his eyes and did his best to stifle a smirk. The after companion-way was being used to hoist out barrels, and Wainwright led Curran forward and then below by the forward hatch. As they departed, Curran heard Mister Erskine roar again, “Master at Arms! Marines to the quarterdeck, and lay a guard on the prisoner.”

Descending to the gun deck, Curran could feel the heat of the great black camboose stove. The smell of roasted meat came to him, and as they passed down the starboard side of the galley Curran watched as the mess cranks lined up before the stove. Big scoops of lobscouse and wedges of cabbage were being thumped into growlers to be carried to individual messes. Wainwright led Curran aft through the happy jostle, but only half the mess tables had been lowered, owing to the liberty men going ashore.

“Where did you come from, sir?” Wainwright asked. Clearly, the boy’s spunk returned when he was out from under the first lieutenant.

“Epevier,” said Curran.

“She’s now homebound,” the boy piped. Mister Wainwright was very well informed.

“I was put ashore at Cádiz,” Curran answered. “Epevier’s been transferred to the Atlantic Squadron.”

“Ah, God’s own ocean,” said Wainwright. “Mind ’yer head, sir. Some of them rammers is kept low.”

Curran was already being sized up by the men gathering at the mess tables hanging between the guns. Like the news of mail, the fact that a new officer was reporting on board was already known throughout the ship.

Curran followed past the starboard 24-pounders, all bowsed neatly, their tackle laid just so, the lines faked down, and round shot and bar glistening in their racks. Over each gun was painted a name: “Liberty’s Trumpet,” “Honey Don’t,” and “Woolybooger” were a few of the standouts among the midships battery. Curran became aware that Wainwright was talking again; he would soon discover it was something the midshipman almost never stopped doing.

“I wish I was in the Atlantic Squadron, sir,” said Wainwright. “Of course, here we’re supposed to be chasing Barbary pirates, Ay-rabs, sir, Tripolitans and Algerines. Broke the treaty they had with Mister Jefferson and have been none to kind to Mister President Monroe, neither. But they know better than to sail when we’re about. It’s lucky for them that what we see is mostly empty water.”

That patrols could be monotonous Curran knew already, but aboard Enterprise apathy did not seem to be much in evidence. What Curran had seen on deck and below told him that Enterprise was a happy ship, her men well fed and content, and her rigging and weapons in as good an order as he’d seen on any flagship. They went down the ladder, Wainwright offering his opinions of both the present administration in Washington, politicians in general, the Navy Department, and Republicans and Whigs, and by then they were aft of the mizzen.

“Wardroom’s straight ahead, sir. Compared to the mids’ berth, a palace! Your cabin ’ull be fourth down the starboard side. It’s just been painted, and two whale oil lanterns which I supervised bein’ put in and squared away. You’ll have Doctor Darby to larboard and Mister Kerr just forward. Both snore, but not as bad as the gunner. I’ll see that your things are put in, sir.” The midshipman opened the door to the wardroom but did not set foot into officer’s country.

“Thank you, Mister Wainwright.” Curran saw that the wardroom was empty but for the steward laying a cloth and plates. He turned in the doorway. “Mister Wainwright, I wonder if you might explain something for me?”

Wainwright blanched slightly. It was only yesterday that the first lieutenant had asked him the difference between a French bowline and a snatch tackle. Wainwright’s explanation had failed so spectacularly that he had been sent to the masthead with a cake of soap between his teeth. “A nautical explanation, sir?” Wainwright quavered.

“A general one,” Curran said. “Why was it that Constellation and Enterprise did not exchange boats? As far as I could tell, the ships did not even hail each other.”

Wainwright became very grave and he said, “Oh.” After that, there was a silence of many seconds.

Curran began to understand Erskine’s quick exasperation. “ ‘Oh’ is not an answer, Mister Wainwright.”

“You don’t know, sir?”

“Do you not find it unusual that two United States naval vessels did not speak to each other in a harbor three miles across?”

“I thought the whole Navy knew, sir.”

Curran managed to say patiently, “Perhaps if you tell me, Mister Wainwright, the entire Navy will know, for I find that I alone have not been let in on this highly esteemed, perhaps even world-changing piece of information.”

Wainwright stammered, “It was that duel, sir.”

“What duel?”

“It was in Italy. At Leghorn, sir, there by Livorno. It was our own Cap’n Pelles that shot off Captain Edmund’s nose, over an operatic lady, in the year seven.”

THE MARINE OUTSIDE THE GREAT CABIN DOOR CAME TO ATTENTION WITH A moderate clash of arms, brought his musket vertical, and said with great enthusiasm, “Good evening, sir.” Having completed his duty as a human door-knocker, the Marine stared earnestly into Curran’s face until above them both the ship’s bell tolled four times, two strokes and two. The Marine then smartly turned about, opened the mahogany door, and said, “The captain will see you immediately, sir.”

Curran placed his hat under his arm, balanced the sailcloth parcel that held his orders and certificates, and walked aft. A short passageway led to the well-lighted great cabin. To starboard was the pantry and the captain’s steward standing quietly; to larboard a sleeping cabin, dark and unknowable except for a lantern burning a single taper. Curran automatically lifted his eyes as he entered the great room, fixing his gaze on the six great windows curved gracefully inward from the stern. The captain’s desk was in the far starboard corner, turned at an angle. Four bright lanterns hung from the overhead, and the desk was lit by a green-shaded lamp. The room was quite as glorious as naval hands could make it; the sole of the cabin was covered with sailcloth painted in the Nelson chequer, and on the cabin’s partitions were a barometer, three Breguet chronometers, and an engraved gilt and silver inclinometer, all shined brilliantly. The darkness beyond the great windows was not yet completely black, and it framed Captain Pelles, who was standing with a foot up on the leather-cushioned lockers under the stern lights.

As Curran approached, Captain Pelles put a match to a long clay pipe. Curran turned toward the desk and stopped next to a straight-backed chair placed in front of it. He came to attention and said, “Lieutenant Curran, sir. Reporting aboard from Epevier.”

Pelles turned in a blue waft of smoke. He was nearly as tall as the cabin’s overhead, a large man who moved languidly. The left arm of the captain’s dress coat was pinned up and empty, and in his lapel button he wore the silver medal of the Guerrière action. Curran guessed, correctly, that Captain Pelles had traded his arm for the silver medal and bit of ribbon on his coat.

“Your orders, Mister Curran?”

Standing at attention, Curran still had his orders clamped under his arm. “Yes sir, sorry sir,” he said as he removed the packet and placed it on the desk.

Pelles lowered himself into the chair behind the desk. “You may sit down, Mister Curran.” Deftly, the captain opened the envelope and spread its contents on the baize-covered table. The pipe clinked into a saucer, and Pelles lifted a small pair of half-oval spectacles and hooked them behind his ears.

Curran kept his head level, as his rank required, but he could see that a pale scar traced across Pelles’ forehead and jaw. Pelles was middle-aged, maybe fifty or less, and it surprised Curran that a man this grave and somber could command what appeared to be such a happy ship.

“I read here that you are the son of a diplomat.”

“Yes, sir. My father was posted to Constantinople. American consul to the Sublime Porte of Sultan Mahmud II.”

“How did you come to be in the Navy?”

This question was not an invitation to enter into conversation, and Curran did not intend to spread canvas with his answer. He knew, and Pelles knew, that his family must have had some influence, political influence, to have gained for their son a midshipman’s berth. Pelles wanted a simple, concise answer.

“My father had the honor to do Captain Bainbridge a service, sir, after his capture by the Tripolitans. The commodore was later kind enough to find me a berth with him on President.”

Pelles digested this perfectly normal transaction and tried to separate any animosity he felt for Bainbridge. Pelles knew Billy Bainbridge to be a hard horse and an unpopular captain; by his peers, Bainbridge was considered both unlucky and a bit too eager to please his patrons in Washington. It was, after all, Bainbridge who had surrendered USS Philadelphia so disgracefully to the Tripolitans in 1803.

“You did not choose to stay with Captain Bainbridge?”

“I had no reason to wish to part, sir. It was the needs of the service, and I was transferred to United States, rated master’s mate, then to Epevier whence I have just come.”

“Just so. Just so,” muttered the captain. There was, Pelles had to admit, some good in Billy Bainbridge—he did redeem himself later when he defeated HMS Java while in command of Constitution. Pelles’ severe green eyes held Curran. “You’ve seen much service in the Mediterranean. Do you have the lingo, Mister Curran? The Lingua Franca?”

“That, sir, and the Ottoman’s Turkish, French, Spanish, and most of the Arabic. Sir.”

Pelles grunted and turned his head slightly, lifting the corner of Curran’s file as he read. Free to let his own eyes roam for a second, Curran glimpsed a small portrait placed near the quarter galley; it was of a blue-eyed woman with a full mouth. Her small bosom was not fully covered by a diaphanous gown, and there was a gaggle of awkwardly painted ships in a harbor behind her. Curran had a moment to think perhaps this was the operatic lady.

“Captain Gormly informs me that you are a fine navigator and a tolerable seaman.”

“Thank you, sir.”

“Don’t thank me, Mister Curran. I have yet to form an opinion.” The pipe came up from the saucer, the bowl glowed, and Pelles let the smoke curl up from his lip.

“You passed for lieutenant when?”

“April thirteenth last year, sir. I was made three days ago, sir. Aboard Epevier.”

“Well then, I trust the celestial tables are still fresh in mind. You will relieve Mister Kerr as navigator.” Pelles picked up the leather envelope containing Nolan’s orders. With the dexterity of a card sharp his thumb and forefinger untied the ribbon and drew out a sheaf of papers. “Are you acquainted with our prisoner, Mister Curran?”

“No sir!”

“I did not mean as an accomplice. Are you aware of the circumstances of his confinement?”

“Isn’t he to be hanged, sir?”

“Hanged? That would be a great mercy.” Pelles puffed his pipe and spread the papers on his blotter, looking them over.

A silence passed and Curran tried eventually to staunch it. “Mister Hancock of Constellation said that he was a murderer and a traitor.”

“Of murder he is innocent. Mister Philip Nolan, now our guest, was involved in a duel at Richmond; he prevailed, and to my mind when a gentleman shoots a fool, it is not murder. Mister Nolan’s crime was his association with Aaron Burr.”

Curran tried to think; the western conspiracy and Burr’s trial were many years ago, while Curran was just a child. His comprehension was further muddled by distance, for his own boyhood was spent in the Levant and Europe, and the news that reached him was in the form of newspapers, always weeks and sometimes months old. “Wasn’t Burr found innocent, sir?”

“The court at Richmond ruled that the charges against Burr were not proven. The big flies escaped—rightly, for all I know. Nolan admitted to carrying messages for Burr—and was found guilty for leaving his post to do so.” Pelles sat back in his chair, stuffed an additional pinch of tobacco into his pipe, and puffed it to life. “You and I would have never had any business with Philip Nolan had the trial been a regular one, but it was not. Colonel Burr was a clever man, and he had clever lawyers. He walked free, but an example had to be made. Nolan was a commissioned officer, and it would not do to question the loyalty of the Army.”

“How long is his sentence, sir?”

“It is indefinite, Mister Curran.”

Pelles handed Nolan’s order of confinement across the desk. Curran noted the date and drew a breath; the document was dated five years before the start of the last war with Britain.

Curran read the order silently, astounded and then awed by its simple, terrible severity. “I am surprised, sir, that I have never heard of Nolan.”

“He is a ghost—or as close to a phantom as a living soul can be. His commission was rescinded, he was stricken from the Army list, and his name was blotted from the records of the Military Academy.” Pelles took the documents and placed them back into their worn leather envelope. “It has been the decision of the Navy Department that the circumstances of his confinement be kept in strict confidence. Likewise his dossier, biographical notes, endorsements, and papers.”

Now Curran came to understand the extraordinary conduct of Constellation’s boat, and the strained silence about Enterprise’s cutter as he and Nolan were rowed to the ship. None of the boat crews had spoken because they dared not.

“As you see, Mister Nolan is a special case. And as it was you who has brought him to Enterprise, Lieutenant Curran, it shall be you who will bear responsibility for his custody. You are not at liberty to discuss our prisoner with the officers or sailors of any other vessel, or the persons manning any shore station or office of the American Navy.”

Pelles handed the papers back to Curran. He continued, “You will see to it that around the prisoner there is no talk of home or the politics of our nation. You will ensure that no books, pamphlets, or letters come into his possession in which he could read of our country. Should a newspaper be lent to him, first cut from it the words ‘United States’ even if they appear in an advertisement for a private concern.”

“Yes, sir.”

“Have the carpenter prepare Nolan a cabin aft of the midshipman’s berth. Unless he attempts to escape, he is to have the freedom of the decks during daylight. Once a week he will dine with the officers in the wardroom, and on the second Sunday of each month he will dine with me, in my cabin. At all other times he will take his meals alone.”

“Does he receive mail, sir?”

“He does not. Letters addressed to Mister Nolan are intercepted at Washington City.”

“May he write them, sir? Letters, I mean.”

“He may not write to or communicate with any person without my express permission.”

“I understand, sir.”

“I won’t keep you any longer; I am sure you have much to do.”

Curran stood, clasped his hat under his arm, and made a short bow. Captain Pelles placed his fingertips over the scar on his face, a gesture he made when he was tired.

“You’ll find that I run a taut ship, Mister Curran. Ensure that my orders are carried out.”

THE PLACE THE CARPENTER PREPARED FOR PHILIP NOLAN WAS ON THE ORLOP deck, not exactly adjacent to the midshipmen’s berth, but probably closer than a civilized person would care to lodge. Enterprise had once carried a chaplain, and it was Captain Garret in 1816 who first had the cabin built; as it was below the gun deck and did not have to be cleared for action, the space had wooden, not canvas, walls and a louvered door. Garret was a bit of a fire-and-brimstone sort and had felt that a man of the cloth berthing in close proximity to the midshipmites might compel them to live a godly life. It did not. Parson Hiedgockle preached daily sermons but left the ship amid whispers of a pederastical connexion with a Neapolitan castrato named Velluti. Enterprise never again sailed with a chaplain.

What had been the parson’s cabin had been gradually taken over by the carpenter’s mates, used as a storeroom and hidey hole, and it was not without some grumbling that they had cleared out their adzes, hammers, planes, bevels, mallets, and pots of varnish. After the Marines had thoroughly searched Nolan’s belongings, he was led belowdecks and put in. It was not half an hour later that he was brought a lantern with a candle and could examine the space he had been allotted.

Lifting the light and peering about, Nolan found it to be a dry place, and there was no evidence of rats. Even subtracting the tumblehome of the ship’s hull, his berth and the enclosed deck space were just wider than the span of both arms held out from his shoulders. The overhead too was generous, a good three inches higher than his head excepting the places where the frames crossed. Fiddled shelves had been put in fore and aft, and a hinged plank folded down from the forward partition. Though warped slightly, the board had provision for an inkwell, but the tool marks and paint stains on it showed that it had not been used recently as a desk. The carpenters had taken away all of their stores, leaving only a three-legged stool and one shelf filled with dusty Bibles provided for “Seamen, Sailors, and other various Seafarers” by the evangelical committee of an organization called the Brethren of the Nazarene.

It would not have taken long for Nolan to stow all of his things, but he kept most of them in the sailcloth bag. He hung his coat on a dowel and hook he made long ago on Revenge and placed his chains and manacles on the shelf next to the Bibles. Nolan sat up from the berth when a Marine brought in his supper—a broken chunk of hardtack and a sharp-smelling tankard of water. Judging from this stingy meal, Nolan was sure he would soon be put somewhere else, and he sat back on the berth and crossed his legs.

The ship rode easily at anchor, and the lantern barely moved on its hook. This cabin, though dark, was a much more commodious place than he had ever been kept, even aboard flagships, and he did not allow himself to become settled. He was used to the games sometimes played on him when he was first taken aboard. In his years at sea, Nolan had been the butt of occasional horseplay, and now he calmly anticipated that the ship’s corporal would barge in, tell him to immediately “clamp on his bleeding seabag” and follow him at once to some cramped and damper part of the ship.

For a while Nolan sat listening to the lap of water on the hull (he was six or seven feet below the waterline), and occasionally laughter or an oath would drift down from the midshipmen’s berth. Though an artillery officer by training, Nolan had formed an affection for ships and the way they were built. Not an inch of space was wasted on a man o’war, and he marveled at the ingenious construction of the neat tiers of shelves. They were placed up high as possible so that things might be stacked below and a man might work freely at the folding desk. All of the things he owned could be spaced out neatly on just two of the shelves on the aft partition. Nolan had lived so long with so few possessions that he could not imagine what even a dozen sailors could have kept in all the shelves, sills, racks, and drawers.

In the paucity of his belongings Nolan had become very much like the men who were his keepers. In all his years at sea he had never met a sailor who seemed very much attached to material things. Some prized waterproof trousers or grogram jackets, but these were freely lent to other shipmates, often taken steaming off one back coming off watch and given to another going out into the weather. They did all love money, especially prize money, but even that appeared only to represent the pleasures it could be traded for on land—rum, food, and women. Nolan had never heard of one sailor who did well with even a fortune on shore. The concept of wealth or shrewd advantage in business seemed to repel them. Once at sea, a purse jingling with gold quickly lost the magnetism it exerted on land, and Nolan had several times watched drunken sailors skipping dollars across the water, playing ducks and drakes, rather than come back to the ship with unspent money.

At sea it was impossible for Nolan to feel that he was poor. All of the sailors aboard owned about as much as he did—that is to say the clothing on their backs, one jacket that was more or less better than the other, and enough small sundries to fill a ditty bag. The officers—save, perhaps, the most successful and well married—seldom owned more than the contents of a pair of cruise boxes. Nolan could name more than a hundred officers who slept in hanging cots under scratchy wool blankets and spent what money they earned on pistols, swords, or navigational instruments and never a set of curtains. Every man who has ever taken to the sea is eventually bent to this spartan ethos. Enough is plenty; any more is surfeit. Gradually, Nolan had come to embrace the sailors’ philosophy, living as much as he could in the present.

Nolan heard the ship creak, and someone said “what ho” to the Marine out in the passageway. Six bells, then seven; Nolan dozed, and he heard the sentry change outside his door. Nolan’s Breguet watch had been taken from him while he was aboard USS Amity (Lieutenant Papeneau said it could be used to aid navigation in case of an escape), but life afloat was not reckoned by a clock. It was nearly eight bells in the second dogwatch, what a landsman (or an Army officer) would say was 8 p.m. Nolan heard laughter again, the sound of sailors turned off watch, and the hoots and shouts of some going ashore. Occasionally a boat thumped gently against the hull as liberty men came and went. Eventually the decks became silent, and even the midshipmen quieted down. It slowly occurred to Nolan that the relief had been made, the standing orders were in effect, and any new orders had by now been carried out. He might not be rousted out this watch at all, and it was increasingly likely that he would be left in this cabin overnight. The thought astounded him—these were the best quarters he’d had in nearly twenty years at sea.

With a stamp, the sentry came to attention outside the door. Nolan heard the Marine say crisply, “Good evening, sir.”

There was a knock, and Nolan rose from the berth. As the door opened, the Marine snapped back to attention, a wonderfully blank-faced and mechanical creature. A shadow moved just on the other side of a lantern, and Nolan made out the silhouette of an officer.

“I came to see that you were settled,” Curran said.

There was slightly more light in the passageway than in the cabin, and Nolan answered to a shadow, not quite able to see the face. “I am, most handsomely,” Nolan said.

Curran glanced into the cabin and saw that Nolan was still clutching his coat and seabag.

“You have not stowed your things?”

As Curran stepped into the light, Nolan made out the face of the man who had taken custody of him on the pier. To Nolan, the man seemed even younger than he had in daylight, surely not more than twenty-five, though he had nothing of a casual air about him.

“Is this where I am to stay?”

“It is,” Curran replied. “Do you have a complaint?”

“No, sir, I do not.” Nolan tossed his seabag onto the berth. “If it was you who put in a word for me, I thank you.”

“I said nothing on your behalf.”

“Well, thankee, at any rate. On Hornet I was kept in a scuttle.” Nolan upended his bag and dumped his things on the berth. Curran saw that all the man owned did not cover half of the mattress. A razor, a scrap of towel, pieces of wool and cotton cloth, and a set of tissue patterns traced on paper that made Curran think that Nolan made his own clothing.

“Have you eaten?” Curran asked.

“I have been fed.”

On the plank table Curran saw a gray-yellow rectangle of ship’s biscuit—the corner of it moved as a weevil worked free. A dented can was next to it, leaking a not quite transparent liquid onto the middle of the desk.

“What is this?” Curran said to the Marine.

“It is salt cracker and bilge water, sir.”

Curran dropped the biscuit into the pot and handed it to the sentry. “See that the prisoner is fed a full portion from the mess deck. He is to have the regular ration, as well as ship’s water.”

The Marine was away at once. Nolan sat back on his berth, wary, considering. He said after a pause, “Well, I thank you then, Mister—”

“Curran. Now sir, about the terms of your confinement.”

“Ah. I know that I pose somewhat of an imposition. I will try to give as little trouble as possible.”

“I would be obliged for that. In return you are to have the run of the ship during the hours of daylight. I will curtail this privilege if you attempt to escape or violate the conditions of your sentence.”

Nolan waited for the inevitable “additional modifications,” for although every ship that had received him carried out the provisions of his sentence to the letter, some captains piled on amendments to the orders, sometimes for their own convenience, sometimes for their own amusement. Nolan waited for a list of off-limits places—the maintop, the boats, the powder magazines—and a roster of persons to whom he could not speak—midshipmen, the quartermasters, sometimes even the yeomen and clerks.

Curran added no extra conditions, and the pause lengthened. Nolan finally mumbled, “I am free to move about the ship?”

“During daylight, sir. After supper and retreat you may move about below-decks. You are to retire to your quarters at lights out.”

In his years in custody Nolan had rarely been granted this much autonomy. He drew a breath and then held it, like a man considering an unexpected move on a chessboard. He looked at the floor of the cabin, thinking. As Curran regarded Nolan, he began to form the impression that during his confinement the prisoner had lost something of the deportment of an officer. Nolan was given to speaking very quietly, often not looking an interlocutor in the eye. Curran wondered if perhaps the prisoner had lost some of his mind. For his own part, Nolan was still uneasy that this might all be some elaborate practical joke. He did not wish to give offense, especially at the start of a new commission, but he did not wish to be made a fool.

“I am to extend an invitation to dine with the officers of the wardroom, tomorrow at supper.”

“An invitation to me?” Nolan asked.

“Do not mock me, sir,” Curran said coolly.

“I meant no offense, Mister Curran. The circumstances of my confinement, you understand, have varied from ship to ship. I am sometimes practiced upon.”

“I am not in the habit of amusing myself at the expense of others, sir.”

The Marine returned, his musket slung over his shoulder. In his hands he carried a wooden tray piled with bread and ham, a piece of pale yellow cheese, a dollop of yellow mustard, and a pot of table beer.

“It’s the ration, sir,” the Marine said. “Old Chick says that there ain’t no hash what’s still hot, so it’s cold pork, soft tommy, and small beer. There’s some of that hard Spanish cheese what’s just come aboard, too. Same as the watch has for midrats.” The Marine handed the wooden mess kid over to Nolan. “Will that do, sir?”

Nolan considered that if this was a joke, it was being played with elaborate and generous hospitality. He said, “Yes, it will do very well.”

Nolan took the plate, and Curran saw the prisoner’s reserve melt away into astonishment and pleasure.

“Captain Pelles has directed that you dine once a week with the officers. On each second Sunday, should the captain find himself at leisure, you will be invited for dinner in the great cabin.”

“Captain Pelles, is it?” Nolan asked. “Well, I am honored. Yes, of course. Thank you again.” Nolan placed the tray onto the folding table and stood beside it, moving his eyes to the loaf—soft baked bread made from white flour—and then he looked at the sentry and then to Curran.

“I’ll leave you to your supper.”

Nolan bobbed his head, said something obliging, and pulled the short stool up to the table.

“Good evening, Mister Nolan.”

Nolan shifted a mouthful of ham into his cheek and said, “A very good evening it is, Mister Curran.” Swallowing, he added, “Thank you for my supper.”

Curran walked aft to the ladder as the sentry closed the door and threw home the bolt.