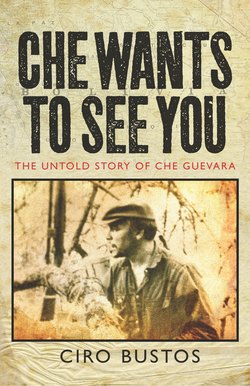

Читать книгу Che Wants to See You - Ciro Bustos - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеIntroduction

By Jon Lee Anderson

It has been nearly five decades since the epic life-and-death story of the Argentine-born revolutionary Ernesto ‘Che’ Guevara entered into the modern literary canon. The posthumously published diary of the literate, handsome young man who sought to bring socialism to the world through armed revolution and died doing so in Bolivia in 1967 rapidly became an international cult classic, a tragic new bible for a rebellious generation. The unavoidable parallels between the end of Che’s life and the mythologized passion of Christ made his story all the more potent, helping to ensure his legacy as the ultimate symbol of sixties idealism. Today, Che Guevara’s face is one of the most widely reproduced images in the world, universally recognized as an icon of youthful defiance against orthodoxy. In his adoptive homeland of Cuba, where the Castro revolution has endured for over fifty years, Che has become the emblematic patron saint of its officially cherished socialist principles. To millions of youngsters everywhere, meanwhile, ‘Che lives’, as the old slogan goes, if only on their T-shirts, while others seek even now to emulate his example on new battlefields. Not surprisingly, for the few surviving men and women who fought under Che’s orders, life has never been the same.

Of the fifty-one guerrillas of various nationalities who joined Che in Bolivia, most were either killed in action or, like himself, executed after being captured. Only three out of the original eighteen Cubans made their way home again. The two Peruvians died. Out of twenty-seven Bolivian fighters, only seven survived. Most of them were captured and imprisoned; several switched sides and worked to apprehend their former comrades. Every war has its contingent of traitors.

There were three Argentine guerrillas including Che, but only one survived. He was Ciro Roberto Bustos, a young artist-turned-revolutionary, and the author of this memoir. Bustos was already a key operative in Che’s fledgling guerrilla network in Argentina, when, in early 1967, Che summoned him to Ñancahuazú, his new, secret guerrilla base camp in south-eastern Bolivia. Che himself had only been there a few months. Ñancahuazú was supposed to be the training ground and staging post for a future Latin American guerrilla army that would spearhead a ‘continental revolution’ against US-backed imperialism in the hemisphere. Once a Bolivian foco was established, the cadres from Peru, Argentina, and neighbouring countries would ‘irradiate outwards’, taking their revolutions to their homelands. Che’s idea was to spark off ‘two, three many Vietnams’ simultaneously, overwhelming the Americans’ capability to suppress them. In trying to do so, their imperial system would be weakened and destroyed once and for all. Che intended to lead the future Argentine foco himself.

Unfortunately for Che, the existence of Ñancahuazú was discovered by the Bolivian army prematurely, while it was still in the embryonic stage, and while he was away, on a gruelling, six-week training march through the wilderness with his small group of volunteers. This setback coincided with Bustos’s arrival in Ñancahuazú. He was accompanied by a young Frenchman, Régis Debray, a Marxist theoretician who had just published Revolution in the Revolution? a theoretical treatise on the very guerrilla strategy that Che was putting into practice in Bolivia. Debray had come to meet Che and to receive his instructions on creating an international solidarity campaign on behalf of the Bolivian revolutionary cause. Bustos was there to confer with Che on how best to proceed with the Argentine armed underground. A previous attempt at starting a guerrilla foco, in which Bustos had participated, had failed catastrophically three years earlier. Bustos had been a lucky survivor.

Now, the authorities’ discovery of the guerrilla presence at Ñancahuazú had triggered an early initiation of hostilities. As Bolivia’s army sent in troops, and also warplanes, to attack them, Che and his men were forced to go on the run. It was an abrupt end to Che’s hopes for a stealthy, well-organized beginning to his ambitious new revolutionary project. When the enormity of the fiasco dawned on him, Che remarked with characteristic fatalism: ‘So, the war has begun.’

As Che broke up his fighters into two smaller groups in order to escape the army dragnet, Bustos and Debray hiked out of the battle zone in the hopes of slipping away undetected and carrying on with their respective missions. They were immediately arrested by soldiers in Muyupampa, the first community they came to. It was April 1967.

For Bustos and Debray, days of terror followed as they were interrogated by their army captors in Camiri, the garrison town where they were taken after their arrest. An early sighting of them in captivity by a local reporter who took their photograph and published it may well have helped save their lives. Debray’s high-level political affiliations in France (his mother was an official of the ruling Gaullist party) soon brought international visibility to their case, and with it a certain guarantee of protection. A pair of CIA agents, Cuban–American exiles who had been brought in to assist the Bolivian army’s anti-guerrilla operation, showed up, and began to question them more deeply. In the beginning, Bustos used a false name. He was Frutos, a travelling salesman – but soon, his true identity was revealed. He was forced to admit his links with Che’s guerrilla band in Bolivia, but managed to keep secret his role as Che’s operative in the Argentine underground.

Under pressure from the CIA agents, Bustos drew pictures of the guerrillas he had spent time with and of the Ñancahuazú camp. He did so knowing that the identities of many of the guerrillas were already known thanks to photographs discovered at the base camp. According to one of the CIA agents, who spoke about it years later, Debray ‘sang like a canary’.

It is a fact of life that most people who fall into the hands of their enemies in wartime break under the pressure, and talk. They may try to mitigate or otherwise colour their information, as Bustos did, but they provide it because they have no choice and are usually threatened with death, sometimes having been tortured first. Bustos and Debray were right to feel afraid of their captors; most of the guerrillas who subsequently fell into the Bolivian army’s hands were shot dead.

In the coming months, as their guerrilla comrades were hunted down, Bustos and Debray were brought to trial. For Che himself, the end came on October 9, 1967. He had been wounded and captured in battle, held overnight in a dirt-floored schoolhouse in a tiny mountain hamlet, questioned repeatedly by various officers. He was then executed, shot to death by a Bolivian army sergeant on the orders of Felix Rodríguez, one of the same CIA men who had interrogated Bustos and Debray.

A few weeks later, Bustos and Debray were sentenced to thirty years in prison. Three tedious years of detention in Camiri dragged by, with no end in sight. Then something unexpected, but very fortunate, happened. In December 1970, after a failed military coup, a left-leaning general, Juan José Torres came to power. As Bolivia’s president Torres moved quickly. Bustos and Debray were amnestied, put on a plane and flown to neighbouring Chile. There, the socialist politician Salvador Allende had become president just three months earlier, gave them a warm welcome. (They were very lucky indeed; Juan José Torres lasted only ten months in power before a right-wing officers’ faction overthrew him. He fled into exile in Argentina, where he was murdered by the military junta’s death squads in 1976.)

After a time in Allende’s Chile, Debray returned to Paris, where he resumed his professional life as a professor, thinker and writer. He served as a special adviser on foreign affairs to the socialist Mitterrand government in the 1980s, and eventually broke with his old mentor Fidel Castro, excoriating the Cuban leader publicly for his traits of stubbornness and arrogance; he accused Che of possessing similar character defects.

Reunited with his wife, Ana María, and their two young daughters, Paula and Andrea, Bustos remained in Chile, where he was given work in a publishing house. Shortly before Pinochet’s violent coup against Allende on September 11, 1973, he decided to return to Argentina, and thus narrowly escaped being caught up in the murderous military crackdown that followed. But in Argentina the dirty war against the Left had already begun as well, and Bustos soon found himself at risk. Some of his friends were killed; others disappeared. In January 1976, Bustos requested political asylum in Sweden for himself, Ana María, Paula and Andrea. It was immediately granted. Once in Sweden, the family was relocated to Malmo, the southwestern port town, and there they stayed.

When I met Bustos in Malmo in 1995, I found a man who was in a deeper, lonelier exile than I could ever have imagined. He seemed to be still living in a state of limbo, as if he had left Argentina, but never really arrived in Sweden. After nearly two decades there, he still did not speak Swedish. He was alone, divorced from Ana María, although he saw her and their daughters regularly. He had a few friends – exiles from Latin America like himself – with whom he met up in bars or restaurants. Bustos’s most constant companion, however, was Gema. She was a young, playful German Shepherd, with whom he went everywhere, and who shared his spacious second-floor flat on a residential street.

The nature of Bustos’s exile also showed up in his relationship to his art, for he was a painter who, to all intents and purposes, no longer painted and never exhibited. He explained that it was because of the Swedish fashion for postmodern conceptual art, which he took me to see in a series of galleries around Malmo: I recall a toilet decoratively enamelled with the Swedish royal crest; a photographed dog turd set into a ceramic tile and placed at the centre of the floor of a large room – and so forth. Bustos’s art was painterly and figurative; his canvases hung around his flat and were, to my eye, both beautiful and sad; all of them were large oil paintings of nudes, men and women embracing, reclining, rendered in gorgeous ochre hues, like the hulks of rusting ships. None of them had faces. This disquieting omission struck me as a testament to Bustos’s cauterized existence, symbolic of an extreme and long-lasting pain.

Bustos had not spoken about his revolutionary past to anyone for many years. We began talking, and we didn’t stop. I stayed for a week. What I learned from him during those days dramatically enhanced my knowledge of Che Guevara, of the Cuban Revolution, and of the heyday of revolutionary ferment in Latin America.

At the time, I had been researching Che Guevara’s life for several years, and had learned that there was a consistent pattern of behaviour amongst those people who had been close to the late revolutionary. Most remained clubbishly loyal to Che’s spirit and legacy, as well as to the espoused socialist ideals of Cuba’s revolution, and were generally self-effacing about their own past roles. There were several good reasons for this, other than revolutionary modesty. Many of them had suffered greatly for their allegiances. In the wave of anti-communist repression that had swept Latin America in the intervening years, most had lost close and dear friends, and sometimes relatives, too. Silence was the best way to survive, and then it had become habitual. In the early nineties, however, following the collapse of the Soviet Union, there was a shift in the atmosphere, and some guerrilla veterans began to open up about their past activities, often for the first time.

In Cuba, where I had gone to live so as to better research Che Guevara’s life, an officially sanctioned Che historiography prevailed for years. In the months and years following Che’s death, a narrative of events had been set out and, over time, the script had become unbudging. In this narrative, Che had gone off to Bolivia by his own choice, and in the field, he had bravely fought and died. Che’s ordeal had become the Cuban Revolution’s ultimate passion play, an account of revolutionary sacrifice that helped validate Cuba’s place in the firmament. There were no Cuban failings in this narrative, no deceits nor betrayals other than those committed by ‘others’, a grab-bag of mostly Bolivian characters who, it was implied, were unreliable and had dragged the whole enterprise down. Che’s own published diary suggested there was more to the story, but few were able to question the official interpretation. There were holes in other parts of the chronology of Che’s life, such as the mysterious two-and-a-half-year gap between the time he vanished from Cuba and reappeared in Bolivia. About all of this, however, silence reigned.

With the help of Che’s widow, Aleida March, and a handful of other people who had known him well, I overcame some of the obstacles in Cuba, eventually gaining access to Che’s personal archives, containing several of his unpublished diaries. This gave me a much greater insight into Che’s thinking at crucial points in his life. As I travelled beyond Cuba to conduct interviews and research in Argentina, Bolivia, Mexico, Russia, and other countries, I realized that I could take very little of the received wisdom about Che’s life for granted. Mythology, urban legend, and, in some cases, intentional obfuscation clouded the real narrative, and it took both detective work and luck to separate fact from fiction.

One of the least satisfactory chapters in the official narrative of Che’s life was the so-called Salta episode, a guerrilla expedition to northern Argentina that he had organized and entrusted to an Argentine protégé, journalist Jorge Ricardo Masetti. In April 1964, after less than a year in the field, ‘la guerrilla de Salta’ had ended in disaster, with most of the fighters involved either killed or captured. In the debacle, Masetti, leader of the self-described EGP, or Ejercito Guerrillero del Pueblo, had vanished, never to be seen again. Afterwards, it was rumoured that Masetti, who had named himself Comandante Segundo, had actually been Che’s advance man for the Argentine revolution he’d supposedly hoped to lead, but the Cubans denied this. They dismissed the Salta fiasco as a minor event, just one out of a long list of unsuccessful guerrilla focos that Che had organized. Neither was there any indication that the failure of Salta had anything to do with Che’s final, fatal mission to Bolivia a few years later. But it did, of course, and Ciro Roberto Bustos, who had been written out of the history books as a marginal character, had played a crucial role in both.

It was Che’s widow, Aleida, who helped set things in motion. She arranged for me to interview Alberto Castellanos, a Cuban who had been one of Che’s bodyguards and was a survivor of Salta. From the amiable Castellanos, I learned that Che had personally planned the Salta expedition and held high hopes for its success. He confirmed that Che had intended to come and lead the guerrillas himself once the foco was up and running. He had been captured and had spent three years in prison in Argentina, but had fortunately managed to keep his Cuban identity secret. Castellanos didn’t go too deeply into the causes of the debacle, but urged me to talk to several of the Argentine survivors, and he contacted some of them on my behalf.

I travelled to Argentina, where I met with Héctor Jouvé, who had been Masetti’s deputy. Like Castellanos, Jouve had been captured. He had spent ten long years in prison, however. For the first time ever, he spoke about what happened in Salta. As he did, a picture of horror began to emerge. It became clear that one of the main reasons the foco had failed was because Masetti had effectively gone crazy soon after he and his men had entered the jungle. He had become doctrinaire and bullying, and at the first signs of weakness amongst his untrained followers, mostly young volunteers from Argentina’s cities, Masetti saw crimes punishable by death. After impromptu trials in the jungle, he had two of them executed. While Masetti was busy terrorizing his followers, a local contingent of carabineros, Argentina’s rural paramilitary police force, was dispatched to the area where the guerrillas had installed themselves after reports of armed strangers had raised suspicions. As would occur a couple of years later in Bolivia, the guerrillas engaged the intruders in a firefight, prematurely alerting the authorities to their presence. Reinforcements were sent in to hunt down the guerrillas, and Masetti’s foco was quickly routed. Jouvé was the last man to see Masetti alive. He said that he suspected that Masetti had either starved to death where he had left him stranded or become lost, in the cloud forest, or else had committed suicide.

Jouvé spoke fondly of Bustos, whom he called ‘el Pelao’ – Baldy – and described him as Che’s point-man in Salta, someone who could shed a great deal of light on its long-buried history. He suggested I talk first to Henry Lerner, another Salta survivor, who was living in Spain.

In Madrid, I learned that Lerner had also been marked for execution by Masetti. Lerner had been spared at the last minute. It seemed less than coincidental, however, that Lerner, as well as the two other men Masetti had executed, Pupi and Nardo, were Jewish. Lerner was keenly aware of this fact but said he had always resisted the notion that Masetti’s enmity might have been motivated by anti-Semitism. But as we dug up the past, old suspicions returned. Like many of Argentina’s radicals of Lerner’s time, Masetti had come out of the Peronist movement, which had bewilderingly managed to straddle the political spectrum from the ultraright to the ultraleft. As a younger man, Masetti had belonged to the Tacuara, a virulently anti-Semitic Catholic group modelled on Spain’s Francoist Falange. Although he had since become a man of the Left, it seemed possible Masetti never reconciled his two extremes, and once in the jungle, the power he had acquired that brought out the worst in him.

After my meeting with Henry Lerner, Bustos told me to come see him in Sweden.

In Malmo, Bustos confirmed what Jouvé, Castellanos and Lerner had told me and added a great deal of important additional detail. He confirmed the connection between Salta and Che’s subsequent expedition to Bolivia, and revealed that Che had been planning an armed revolution in Argentina as early as 1962. Bustos, who had arrived in Cuba as an enthusiastic revolutionary volunteer in 1961, had been quickly recruited for Che’s Argentine project by Alberto Granados, Che’s old Motorcyle Diaries buddy. Granados had moved to Cuba after the revolution and had lived there ever since.

Bustos disclosed that he and the other members of the Che’s Argentina team had received their initial training in spycraft and the use of weapons in Cuba and then, following the Missile Crisis, had gone to Czechoslovakia and onto Algeria for more training. He acknowledged Masetti’s harshness and confirmed the brutal executions Massetti had ordered, as well as his own part in one of them. In the case of Pupi, the first victim, the execution was botched, he explained, and he had been forced to fire the coup de grace, shooting a bullet into the mortally wounded man’s head.

Bustos had survived the Salta catastrophe otherwise unscathed and made his way back to Cuba. There, Che had asked him to return to Argentina as his liasion with the leftist underground there, and had eventually summoned him to Bolivia, where fate awaited them both.

In the end, history is complicated. In the story of Che Guevara’s bloody demise in Bolivia, there has long been a tendency by survivors, as well as historians and analysts, to seek out culprits for what happened. The Bolivian army and the CIA agents, who secretly executed Che and many of his comrades, didn’t expound a great deal about what they had done after the fact. They didn’t need to, because they had won a battlefield victory, but they also had their war crimes to keep quiet about. For the Cubans, meanwhile, Che’s defeat was casually attributed to the faults of ‘others’, a potage that included the betrayals of some of the captured Bolivian deserters, as well as Bustos, for the drawings he had made in captivity. Others blamed the Bolivian Communist Party leadership, which had withdrawn its support for Che once he was in Bolivia, leaving him exposed and vulnerable. The area chosen for Che’s base camp at Ñancahuazú had been selected by the Party leadership and clearly had been highly unsuitable; many believed this was no accident. Any mistakes that had been made by members of Cuba’s secret services, meanwhile, not to mention the decisive role played by Fidel Castro himself, who had chosen Bolivia as the theatre for Che’s foco, were swept aside. The story that Ciro Bustos tells here is a candid one in which we can see that the final chapter in Che’s life was the result of a complicated alchemy that included all of the above, not to mention luck, or the lack of it, and, not least, Che’s own decisions. In the end, we are reminded, the outcomes of the mightiest of human enterprises are dependent on human nature.

Che Wants to See You is also the account of an extraordinary period in contemporary history in which thousands of young men and women around the world, inspired by Che Guevara and his Cuban comrades, believed they could change the world through armed revolution. They mostly failed, but left behind a remarkable legacy of shared idealism and sacrifice.

This book is ultimately part of that legacy, the journal of a life lived to the limit in pursuit of an ideal, with all of its consequences. There are many memories here, some of which are bittersweet jewels. Here is Bustos recalling how horseflesh, which he was forced to eat in order to survive in Bolivia, reminded him of the smell of Pupi at the moment he shot him dead. And there is the time when he overheard Che recite aloud verses from the Spanish poet León Felipe as they marched together through the Bolivian bush. It was one of the worst of times, but for Bustos, it is a most cherished memory of Che Guevara and of their shared revolutionary life.