Читать книгу Che Wants to See You - Ciro Bustos - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеPreface

This is a book about remembering, in two senses of the word. It is a memoir, not a biography, nor a book of history, political theory, or essays. It is the story of a stage in my life that goes off at tangents, into the future and into the past, when need be. The important thing is not my life, but what happened around it and what I witnessed. So writing in the first person singular is inevitable, because I am only recounting what I saw, heard, felt, listened to and read, as well as what I did, thought, and occasionally said. Nothing is presumed, added or invented. It is not a fictional account, these are real events, some of them small, and others transcendental, and they have all come together one by one to form my identity. There was no other way to tell this story than by looking frankly and openly inside myself; it is personal and unique. I am present throughout the book not for self-glorification, but to testify through all my senses to what was happening around me.

It is also a book written from memory. The avalanche of information I collected over the years overwhelmed my lack of writing experience, and I found that although I had such and such a detail to hand somewhere, I couldn’t get at it without wasting days and weeks in a fruitless search. I eventually reached such a state of uncertainty, each doubt multiplied by hundreds of versions, that I chose to abandon all the material I had accumulated – cuttings, photocopies of articles and other kinds of documentation – and rely solely on my memory. A quote from García Márquez, which I read opportunely, supported me in my decision: ‘Truth is only what memory remembers.’

For dates and names, I have used about six books on the subject. The rest of the information was there, more or less organized for reference purposes, but always wrong, like coins hidden under tumblers in a magician’s trick. Memory, in any case, is like a coiled spring, waiting to be released. Sometimes fascinating things occur, comparable to the fishing technique of Laplanders who spend hours sitting beside a hole in the ice, with a fishing line rolled round their finger disappearing into the invisible waters, tugging on it gently from time to time, unperturbed, nothing happening, until, suddenly, a magnificent specimen emerges from the ice. I spent days and weeks with my mind blank, tugging the line a little and letting it go, until the whole spool unravelled unexpectedly. Sometimes it seemed as if someone was sitting inside my head dictating to me or, rather, that they were manipulating my fingers. Images appeared that I had not thought of since those days: meals, places, vehicles, situations, even music and smells. Naturally, not all the millions of moments that form a life are there. I read somewhere that the psyche filters bad memories that could harm the spirit, just as the body heals wounds.

It might seem as though some things are missing from the historical context, such as, for example, the nature of revolutions, and not just the Cuban. But to me this is a different topic, one that merits special analysis or scientific examination from defined political and ideological stances, and that is not the aim of this book, nor is it within my capabilities.

A large part of the book takes place at a time when almost everybody, including 90 per cent of its current detractors, loved the Cuban Revolution, even if the majority of them used it shamefully. There is no way anyone can accuse me of that. Nor can anyone surmise any financial interest on my part. For almost forty years I have refused any offer that would have meant an inappropriate use of the events and, particularly, any use of them for personal gain.

Comments about the form and style of the text are inevitable because I am not a professional writer. But some clarification is not only possible but necessary. For example, something that friendly pre-publication readers pointed out: Che’s Cubanized Spanish. While it is true he spoke with a pronounced provincial Argentine accent – that’s unquestionable – he always used Cuban vocabulary. Not even in nostalgic asides to friends did he indulge in Argentine vernacular. Also, some of the information revealed might make people uneasy, since it has been secret for decades. But it is no longer secret. Some of it has been disclosed by the Cubans themselves, in biographies or enemy documents, not forgetting the international actions of the Revolution’s troops.

There were names I could not find, lost in the whirlwind of time. Others, which no doubt exist in my books and documents, were simply left out. But, in any case, it was never my intention to produce a catalogue of events or a telephone directory. I would rather admit I don’t remember, as has often happened, than pretend or invent. Of course, there will be unintentional errors in names, dates, chronology, etc. Transferring memory to paper presupposes some poetic licence despite one’s best intentions, because images cannot be copied and pasted like new technology. They have to be turned into words and phrases with a certain harmony, and, if possible, elegance. And, yes, as happens when we recount our dreams, we can’t capture them accurately before they fade and become slightly deformed. I don’t think the errors are serious enough to distort the story, because I would have noticed, but in any case they would not be intentional or in bad faith.

Undertaking this task so long after the events, despite the insistent voices of friends urging me to do so earlier, has created a double slippage. First, potential readers – except for a few survivors – will be of a new generation, unfamiliar with the pre-globalization era, when more defined ideological camps implied a greater commitment to political struggles, even if only in writing, and therefore a greater recognition for the characters behind these words. These days, if it were not for the T-shirt industry, no one would even know what they looked like. Second, this book was written far from the natural environment in which the events took place, at the opposite geographical pole, and this has influenced my writing. Alone with my ghosts, without clear reference points, their lights and shadows are reflected on my keyboard.

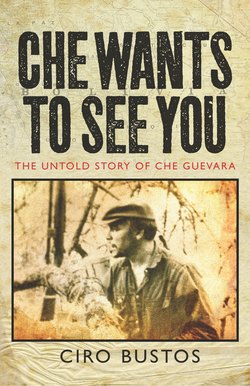

Ciro Bustos

Malmö, April 2005