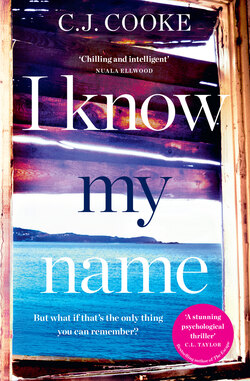

Читать книгу I Know My Name - C.J. Cooke - Страница 11

18 March 2015 Komméno Island, Greece

ОглавлениеI wake to find myself in bed in an attic room. Dust motes visible in the air, picked out by bright sunshine streaming through a porthole window. The ceiling is criss-crossed with ancient wooden beams and spiderwebs in the corners. Hewn stone walls and a cloying stench of dust and damp make the room feel like a cave.

I pull myself upright, gasping from the pain in my head and from a series of aches that announce themselves in my right shin and ankle, my upper back, all the muscles in my neck and forearms terribly strained. It feels like I got in the way of an elephant stampede. I reach around and touch the spot where my skull had been cut open. No fresh blood, but I can feel where the bleeding has matted my hair.

The events of last night turn over in my mind like stones. The people I met, the ones that saved me from a boating accident on the beach. They were writers, weren’t they? Here on a retreat? I try to summon my name to mind. It doesn’t come, so I say it aloud. My name is … My mouth remains open as though the sound of my name will find its way inside of its own accord. I have the strongest sensation of having left something behind somewhere, and although I pace and try to will it to surface, it won’t reveal itself.

Water. I need water. I move my legs to the edge of the bed and drop my feet to the floor. Cold. I’m wearing a T-shirt with a faded pineapple print on the front and baggy black swimming trunks.

I hobble like a foal towards the door, but when I turn the door knob I find it is shut tight. I tug at it, one hand on top of the other, wrapping my fingers around the knob and twisting with all my strength. The knob turns and turns but the door won’t budge. For a moment I really think I’m going to lose consciousness. With a hand pressed against the wall I let myself sink slowly down to the floor and rest my forehead against the door, taking long, trembling breaths. A large grey spider taps across the floor by my bare feet. I flinch, and in a second the spider is gone, darting into one of the dusty crags in the walls. I’m left with enough adrenalin to lift a fist against the heavy wood of the door, banging it once, twice, three times. I can hear a low murmur of voices somewhere in the house.

Eventually, the door pushes open, knocking into me. Someone swears and squeezes through the gap before helping me to my feet.

‘The door was locked,’ I say, trying to explain.

‘Locked?’ Joe’s voice. He inspects the door quickly and says, ‘Not locked. Always jams, this door. Come on, let’s get you something to eat.’

After shouting downstairs for one of the others he slips a hand on the back of my head and the other firmly on the small of my back. Soon one of the women is there, too, and I recognise her as the kind one from last night, the woman who looked at me with such concern. Sariah. She helps Joe lift me to my feet and, very slowly, we all head down a winding stone staircase, one, two floors, Joe in front of me, Sariah behind, in case I fall.

The architecture of the house suggests it was once an old farmhouse, with remnants from its past hung on the wall as vintage ornaments – old breast ploughs, some fairly mean-looking pitchforks, and the wheel of a chaff-cutter, as well as cow or goat bells. A room at the bottom of the stairs features a rocking chair – I remember sitting there last night, hunched over and trembling – and a beautiful inglenook fireplace that smelled of burnt toast.

The kitchen looks different in daylight – long and brightly lit, with a large range oven, refrigerator, white granite worktops, and a wooden table in the middle surrounded by four wooden chairs. A little decrepit and dusty, but nowhere near as creepy as it seemed last night. The room has an earthy odour about it, as though it’s been unused for a long time, though as I head towards the cooker it gives way to the rich smell of grilled tomatoes and fresh pitta. Sariah says, ‘Let’s get you something to eat,’ and makes for a pan on the hob.

Joe walks me slowly to a chair by the table, then makes for the sink. He’s a good deal younger than I’d placed him last night. Maybe early twenties, a whiff of the undergrad about him. Long, pale, and thin, his black hair standing upright on his head in a gelled quiff, black square glasses shielding his eyes.

He hands me a glass of water, which I gulp down. Sariah fills a plate with the contents of a pan. Dressed in a red skirt and floaty kimono patterned with orange flowers, she looks magnificent: long dark fingers ringed with gold bands, heavy strands of colourful beads looping from her neck, ropes of black hair coiled on top of her head and tied with an orange scarf. She sets a plate of food in front of me – fried cherry tomatoes, olives, pitta bread.

‘Thank you,’ I say, and she grins.

‘Mind if I take a little look at your head?’ Joe asks.

I feel his hands gently touch the wound through my hair at the back of my head.

‘How does it look?’

‘Clean. Some bruising around the area. How’s the neck?’

His fingers brush the sides of my neck gently and he tries to move my head from side to side.

‘Stiff.’

‘I’ll find some painkillers.’

A kettle whistles to the boil on the hob. Sariah walks towards it and begins to make coffee, asking if I’d like milk. It all feels so strange and disorienting. I say yes to the milk but even that seems odd, the sound of my voice distant and distorted. I dart my eyes around the room, willing it to make sense, to become familiar. It doesn’t.

The other woman – Hazel, I hear Joe call her – scuttles in from somewhere else, rubbing her hands and muttering about tea. She’s short and thin, orange curls leaping on her head like springs, an oversized black woollen jumper pulled over a bottle-green skirt. She holds something in the crook of an arm. A notebook.

She stops in her tracks when she spots me, as though she hadn’t expected me to be here. ‘Hello,’ she says warily, and she sits down, placing the notebook carefully on her lap. Her accent is English, like Joe and George.

‘Hello.’

‘Are you going to stay with us?’ she asks.

Sariah answers from the sink. ‘We’re still working out how to get her to see a doctor.’

Hazel glances from me to Sariah. ‘Joe’s a doctor, isn’t he?’

‘I do first aid,’ Joe corrects from the other end of the room.

‘I found these,’ he says. ‘Paracetamol.’

‘Thanks.’ I press a couple of tablets out of the foil and take them with a swig of coffee.

I feel Hazel watching me, her small grey eyes absorbing every inch of me. ‘You were in quite a state last night,’ she says. ‘It was all very exciting. Do you remember what happened?’

I suspect she means if I remember what happened before I ended up in their kitchen. There’s a smile on her face, as if the sorry state of me amuses her. It makes me wary.

‘And you still don’t remember how you ended up here?’

‘I don’t think so …’

‘What about your name?’

I open my mouth, because this should be right there, right on the top of my tongue. But the space in my mind that should be bright with self-knowledge is blank, closed, emptied.

Hazel’s eyes blaze with excitement at my hesitation. I see Sariah giving her a look of caution, and instantly she looks away, shame-faced.

‘Don’t sweat it,’ Sariah says. ‘You’ve had a rough night, a bump on the head. Give it a few hours. It’ll all come back.’

The sound of heavy footsteps grows louder at the back door. Moments later, George appears, glistening with sweat and exhaustion, his grey vest soaked through. Hazel fidgets in anticipation as he heads towards us.

‘Did you find it?’ Sariah asks.

George shakes his head, too worn out to speak. He’s very overweight and so red in the face that I brace myself for the sight of him falling to the ground with a tremendous thud. He pulls a towel from the shelf above the sink and wipes sweat from his brow and face.

‘You mean, the boat?’ Hazel says in a shrill voice. ‘We’ve lost the boat?’

No answer. Hazel and Sariah watch George as he leans back in the chair and catches his breath. Both of them look worried. The mood in the room has plummeted.

‘What boat?’ I ask, and my voice is small and hesitant. It sounds odd to me, as though someone else is speaking.

‘We rented a powerboat from Nikodemos so we can travel back and forth to Crete for supplies,’ Sariah says in a low voice.

‘The only reason we found you was because Joe and I went out to check that the boat was moored properly during the storm,’ George pants, pulling off his wet boots, and then his socks. The sour smell of sweat hits me instantly. ‘And then we came across you. But the boat’s gone.’

‘I thought Joe said it would likely be washed up on one of the beaches,’ Hazel says.

George tilts his head from side to side, emitting loud cracks from his neck. ‘I’ve checked everywhere, trust me. Boat’s gone. Sunk, most likely.’

‘What will Nikodemos say about his boat sinking?’ Hazel says. ‘He’ll be cross, won’t he? Very, very cross.’

‘What will Nikodemos charge for his boat sinking?’ George corrects. ‘That’s the question.’

‘We’re covered by insurance, aren’t we?’ Sariah says, turning back to the hob to crack eggs into a pan. Her movements are rough, erratic.

George scratches a rough belt of stubble under his chin. ‘We’ll need to work out another way to get supplies from the mainland. Not to mention delivering our guest back to wherever she came from.’

I feel that this is my fault. I don’t belong here. I shouldn’t be here, and I feel helpless and awkward. George and Hazel acknowledge this with a quick glance in my direction, which only confirms that they feel I’m to blame. ‘I’m so sorry about your boat,’ I say.

‘We’ll work it out,’ Sariah mutters without turning, and I wonder if she’s detected that I’m feeling pretty awful. Joe is at the back door, a bundle of peaches gathered in the hem of his black T-shirt. George opens his mouth and begins to tell him about the boat situation, but Sariah cuts in.

‘Want some breakfast, Joe?’

Joe dumps his peaches on the worktop. He rubs his hands and glances at the pan on the hob. ‘Thanks.’

‘George, you want some?’ Sariah asks.

‘Okey-dokey.’ He glances up at me. ‘Sariah’s the cook in this operation, in case you hadn’t noticed.’

‘And what am I in this operation?’ Hazel pipes up from the table.

‘The cleaner,’ Joe says through a mouthful of omelette. He looks at me. ‘Hazel likes to clean and tidy everything in sight. She’ll take a glass out of your hand before you’ve even finished drinking to wash it.’

Hazel shrugs, clearly bristling. ‘Nothing wrong with being clean, is there? Next to godliness.’

‘Still, I’d hold on to your plate,’ Joe tells me. ‘She’ll take it off you.’

‘And what about you?’ I ask Joe. ‘What do you do?’

He tosses a cherry tomato in his mouth. ‘First aider.’

‘She means, what do you do here, dumb-dumb,’ George says.

‘Oh. Well, I tagged along, didn’t I?’ Joe says. ‘I’m the – provider of medical attention?’

‘House first-aider,’ George interprets.

‘George is the fixer,’ Hazel tells me.

‘And what does that mean?’ George asks.

‘It means you fix things, George,’ Joe says. ‘Unless “fixer” is Mongolian for “grumpy old git”.’

‘I’ll fix you in a minute.’

‘See?’ Joe says to me, arching a thick black eyebrow.

Sariah brings the last of the food, a plate of chopped figs and tomatoes. She removes her apron and slings it on a hook by the oven, then sits at the table beside me while George cups water on his face and armpits at the sink. Despite how terrible I feel, I’m incredibly relaxed in their company, as though I’ve known them for ages. It makes an otherwise alarming situation quite bearable.

‘So, if you can’t remember your name, how come you can remember how to talk?’ Hazel asks.

‘It doesn’t work like that,’ Joe tells her. ‘It’s called amnesia. It doesn’t stop people’s ability to function.’

She purses her lips. ‘So, you can’t remember if you’ve got any weird fetishes?’

‘I don’t think so,’ I tell her.

She looks thrilled, a sudden energy sweeping through her. ‘I want to study you for my new book. Do you mind if I ask you some questions?’

I go to say that I don’t mind, but Joe interrupts.

‘Look at you, such a busy-body,’ he tells Hazel, throwing her a wry smile.

She shoos his comment away with a wave of her hand. Then, to me: ‘Do you know what you like to eat?’

‘I guess I liked what I just ate.’

But Hazel isn’t satisfied. She tosses question after question at me: who’s the current President of the United States? What year it is? What’s the name of my primary school? When was I most embarrassed? And so on. I’m still too foggy-headed to answer most of these, though I’m relieved that I’m aware of what year it is. But not who I am.

‘You could be anybody,’ Hazel says, at once exasperated and curious. ‘How do you have a sense of who you are if you don’t remember anything?’

‘Well, how do any of us have a true sense of who we are?’ Joe interjects, making quotation marks with his fingers. ‘We’re all of us many people in a single skin.’

‘I’m not,’ George says. ‘Cripes, you make it sound like we’re all … what are those Russian dolls called?’

‘They’re called Russian dolls,’ Hazel says drily.

‘Identity is performance,’ Joe says. ‘Ask any psychoanalyst and they’ll tell you the same.’

Hazel lifts an eyebrow. ‘Well, next time I bump into a psychoanalyst on this uninhabited island, I will!’

I’m shocked by this. ‘“Uninhabited?”’

Joe nods.

‘This whole island is uninhabited?’

‘An uninhabited paradise,’ Sariah says dreamily. ‘Just this old farmhouse and a few Minoan ruins. And us.’

I glance out the window and see a patch of dry earth rolling down to the ocean, nothing but blue all the way to the horizon. Hazel starts to tell me that the nearest island is Antikythera, which is eight miles away, but this sparks a debate with Joe about whether Crete is closer. I’m no longer listening. Eight miles of ocean to the nearest town. I’d assumed that there would be other people on the island, people we could speak to in order to provide answers to my situation, or who might help locate the missing boat. That I would be able to contact the authorities and find out where I came from.

‘But – how do you get supplies?’ I ask.

‘There used to be a big hotel on the south side,’ Hazel tells me, as if in confidence. ‘There was a restaurant, a few shops, even a bowling alley. But they closed it down last year. The recession, you know. That’s where we got our supplies before. Nikodemos – the man who owns the island – well, he loaned us a powerboat this time round …’

‘… which seems to have sunk,’ adds George.

‘There’s no Internet here, either,’ Joe warns.

No Internet means I can’t use social media or Google to search for reports of a woman of my description going missing from Crete.

‘Nikodemos gave us a satellite phone,’ Sariah says, observing my unease. ‘And thank goodness. With the boat gone, we really would be stranded.’

This, I do remember. The satellite phone that George pulled from his pocket last night. The phone they said they’d use to contact the police on the main island.

‘Have the police been in touch?’ I ask quickly.

‘I called them again first thing,’ George says, and for a moment I feel relieved. But then he adds: ‘No one’s filed a missing person’s report. I asked them to correspond with some of the stations in the other islands and they said they would.’ He shrugs. ‘Sorry it’s not better news.’

‘Maybe we could call the British Embassy?’ I suggest. ‘Anyone looking for me is likely to leave a message there.’

‘Okey-dokey.’

He pulls the phone from the pocket of his jeans and extends the long antenna from the top. Then he rises sharply from the table, dialling a number and heading towards the window, apparently to get a better signal.

‘I need to be connected to the British Embassy, please?’ I hear him say.

My heart racing, I stand and make my way towards him, full of anticipation.

‘Athens, you say?’ He holds the phone away from his mouth and tells me, ‘There’s no British Embassy on Crete. The closest is Athens.’

When I ask how far Athens is, the answer is depressing: about sixteen hours from here by boat, which of course we don’t appear to have.

George turns back to the phone. ‘Hello, yes? Yes, I wish to report a missing British citizen. At least, we think she’s British.’ He glances at me, expectant, but I have no answer to give. I don’t know whether I’m British or not. He turns back to the phone. ‘She’s turned up here on Komméno and can’t remember much about anything. Yes, Komméno. We’re about eight miles northwest of Crete.’

He gives a description of me and nods a lot, clicks his fingers for a piece of paper and a pen and jots something down. Then he says goodbye and hangs up.

‘No one has contacted them about a missing British woman,’ he sighs. ‘Though of course it would help if we knew your name.’

Sariah frowns. ‘They’re based in Athens, though,’ she says. ‘Maybe we should try the police in Chania?’

George looks reluctant but dials a number. After a few moments he begins pacing the room, looking up at the ceiling. ‘No signal,’ he says. ‘I’ll try outside.’ He goes out the back door but returns a few minutes later shaking his head, and I can’t help but feel stricken. No one has reported a missing person. No one has reported me.

Despite all their efforts to make me feel at home, the news saps what small amount of my strength had returned. My head and neck begin to throb again, and – bizarrely – my breasts are sore and hot; they feel as though someone’s injected molten lead into them. As Sariah begins to clear the table I pull my T-shirt forward subtly and peer down. My senses prove right: my breasts have swollen into two hard white globes, blue veins criss-crossing them like maps.

‘Are you all right?’ Sariah asks.

I let go of the neck of my T-shirt, embarrassed. ‘I’m not feeling so good. Would you mind if I had a lie-down?’

Sariah tells me of course it’s fine, and Joe is already on his feet, offering to help me to my room.

‘Are you sure you don’t need me to check you over?’ he says, helping me up the stairs. I tell him that I’m fine, but the pain across my chest is alarming and bizarre: a strange tightening sensation that wraps right around my back. It feels like someone has rammed hot pokers through my nipples.

By the time I get to the bed I’m in tears, unable to hide it any longer. I can’t decide if I’ve torn some muscles in my chest or if I’m having a heart attack. Sariah is suddenly there by the bed, Joe on the other side, both of them asking me what’s wrong, why am I crying.

I just want to sleep.