Читать книгу Those Wild Wyndhams: Three Sisters at the Heart of Power - Claudia Renton - Страница 15

EIGHT The Summer of 1887

ОглавлениеIn January 1887, while staying at Clouds, Mary realized to her horror that she was pregnant again. She chided ‘Naughty Wash’ for ‘pinting [sic] too soon after Betsey at Panshanger’,1 breaking the news in a carrot-and-stick manner: ‘if ou comes veggy early! Migs will receive ou in cot & no more precautions needed, for Migs is quite certainly in the family way,’ she told him.2 Hugo had been expected back several days before. Mary suspected, with good reason, that he had been delayed by another woman’s charms. She used the promise of sex to entice him back.

Mary was furious about being pregnant. Her younger son Guy was barely six months old. Mananai was due to be presented that spring. Mary had been looking forward to showing her younger sister the ropes in her first Season. Pregnancy required her to scale down her social activities. It made her feel fat, dull, unable to compete socially among her friends. The mid-Victorian days of ten or twelve children were past. Souls women, appreciating their figures, their health and their consuming social lives, did not have many children.3 There were ways of achieving this. Carefully coded advertisements in women’s periodicals recommended purges of pennyroyal and compounds of aloe and iron that would restore an ailing young lady to her former good ‘health’. It seems that at least some of Mary’s friends employed these, but Mary decided that she ‘daren’t send for Zach’s stuff its too naughty’, and resigned herself to the inevitable:4 ‘Me looks forward to it [the pregnancy] with disgust & loathing … my season with Mad knocked on the head. Migs propose Pints dispose,’ she mourned.5

Mary was still in her first trimester when she attended George and Sibell’s quiet marriage in the private chapel of the Westminsters’ Cheshire house, Eaton Hall. The service was conducted by the Archbishop of Canterbury. Only immediate family on both sides attended. In what must have been a significant blow to George’s ego, The Times reported that the Countess Grosvenor had married Guy Wyndham of 16th (Queen’s) Lancers, with George acting as best man.6 The Wyndhams celebrated the occasion more lavishly on their return to Clouds with a vast tea for Milton’s and East Knoyle’s inhabitants, with a band playing from the terrace, a cricket match for the adults and a bag of sweets and a bun for each child.7 When George and Sibell made their first visit as newlyweds, the villagers followed the still fairly widespread tradition of intercepting their carriage and replacing their horses with eighty men who pulled them up the driveway to Clouds themselves.8

While on honeymoon in the Italian Lakes, George received a telegram from Arthur Balfour. In March 1887, Sir Michael Hicks Beach, Ireland’s Chief Secretary, had resigned, citing cataracts that had left him nearly blind. The grounds for resignation evoked those of Sir George Trevelyan, Cavendish’s successor, whose hair turned completely white within twelve months of taking the job, and who resigned a year after that, pleading to be released from a post that was, in his words, ‘not a human life at all’.9 In a shock appointment, Salisbury now chose his favourite nephew to fill the vacancy. Balfour’s appointment provoked incomprehension at Westminster and jubilation in Dublin: ‘We have killed Cavendish, blinded Beach and smashed up Trevelyan. What shall we do with this weakling?’ taunted the Irish crowds.10 So startling was Robert Salisbury’s decision that it has prompted the suggestion (probably incorrect) that it gave rise to the popular phrase that suggests when ‘Bob’s your uncle’ anything is possible.11 Now Arthur asked George to join him as his private secretary. Citing the Wyndham tradition of public service, George cut short his honeymoon and hotfooted it back to ‘throw my lot in the political boat’.12

George’s new post was a triumph for the Wyndhams, establishing, in the Souls’ fiercely competitive world, how close the family was to the ‘adored Gazelle’. But both offices were dangerous. Cavendish’s and Burke’s murders were still fresh in people’s minds. Arthur, the tenth Chief Secretary in as many years,13 pointed out with typical detachment that Ireland was a place where people tended to lose their reputations, their lives or possibly both.14 Shortly before Arthur’s departure, Mary visited him at Carlton Gardens. It was a Wednesday afternoon, fast becoming their ritual meeting time when in London, for on Wednesdays the House rose early. Perhaps it was the urgency lent by anxiety that provoked what Mary described as a ‘small very private and personal incident (gear changing!)’ in the same downstairs sitting room where they had first kissed a year before. Mary gave no further clues to what the incident might have been, beyond teasing Arthur that it would not appear in his memoirs.15

Some years later, Mary explained to Wilfrid Blunt the exact nature of sexual relations among the Souls. ‘Nearly all the group were married women with husbands whom they loved & by whom they had children, but each had her friend who was a friend only.’16 Those friends’ relationship was ‘a little more than friendship, a little less than love’. So far as Wilfrid could understand, this meant everything but ‘the conjugal act’; or, from the male perspective, ‘Every woman shall have her man, but no man shall have his woman.’17 Later correspondence indicates that Mary and Arthur developed a sexual relationship involving role-play and mild sado-masochism (Arthur’s fondness for vigorous spankings lends disappointing force to the accusations frequently levelled at public-school-educated Englishmen). Quite possibly this ‘incident’ was the first time that Mary – then almost three months’ pregnant – and Arthur engaged in such activities.

Arthur left a few days later, leaving with Frances Balfour a pouch to be opened only in the event of his death. ‘Accidents have occurred to a Chief Secretary for Ireland and (although I think it improbable) they may occur again. If the worst (as people euphemistically say!) should happen,’ said Balfour, Frances was to cut open the pouch with her penknife and ‘read the scrawl inside. It relates to a matter with which only you can deal.’

Arthur did not need to elaborate on these instructions, or on his request that in such an event Frances check through his papers for any incriminating correspondence (Arthur’s preparations for his departure included burning a multitude of letters, many, presumably, from Mary). Fifty years later, an elderly Frances and Mary sat down together to open the pouch. ‘My dear Frances,’ wrote Balfour:

I write this in a great hurry, but as you will only have to read it in the event of my death you will forgive my handwriting. I think you and all whom I love will be sorry that I am not any longer with you. But you will be able to talk it freely over with each other and all whom such an event may concern. There is however one who will not be in this position. I want you to give her as from yourself this little brooch which you will find herewith: and to tell her that, at the end, if I was able to think at all, I thought of her. If I was the means of introducing any unhappiness into her life I hope God will forgive me. I know she will.18

The year 1887 marked Queen Victoria’s Golden Jubilee. The Queen was reluctantly persuaded out of purdah for a Season glittering with magnificent balls, processions and banquets. Mary spent it more quietly in intellectual self-improvement. She was a keen attendee of weekly ethics classes organized by her sister-in-law Hilda Brodrick, who hired a Girton graduate as tutor. The day chosen was Wednesday, so male Souls could join. The small group that gathered each week included Mary, Betty Balfour, Charty Ribblesdale, Lady Pembroke and Ettie Grenfell. The sessions, on themes including ‘Conscience self love etc’ and ‘Kant’, were a qualified success. ‘Miss Anderson gave us a lecture which as none of us (except Betty) knew anything about the subject or had read anything was rather above our heads,’ Mary told her diary, noting that week’s essay: ‘Is it necessary for ethical reasoning, to assume or establish an ultimate end to rational action?’ Attendance diminished as the Season wore on. Mary was just one of three participants at the final class in early July, although their numbers had been boosted when Willie Grenfell and Tommy Ribblesdale joined after the House rose. The triumphant ethicists went out for a ‘farewell ethical luncheon’ that continued into the early hours of the morning: ‘we argued about the word implied & implicit till 1 o’clock & then couldn’t sleep from excitement’, Mary recorded.19

A brief respite followed, as Mary, Hugo, the Ribblesdales and their eldest son Thomas went for a few days to Lyndhurst in the New Forest, staying in the Crown Hotel. The weather was baking, and the Forest even more lovely than Mary had expected. ‘We have been out all today laying [sic] on our backs looking up at the trees [while] Charty read aloud,’ Mary told her mother. Later in the day Hugo, Tommy and little Tommy raced around, hot, flustered and excited, trying to catch butterflies in nets. That night both couples dined with Sir William Harcourt, who had served in Gladstone’s most recent Cabinet as Chancellor, and Harcourt’s wife Elizabeth, and then took a moonlit drive back to their hotel. The trip was a ‘great success’ for the two flirtatious couples.20

Shortly afterwards, Mary went to Clouds. Hugo quickly absented himself, busying himself in London for the Season’s final weeks. Madeline Wyndham proposed that Mary should stay at Clouds for the rest of the summer rather than return to Stanway. With some misgivings, Mary broached the idea with Percy. After ‘incubating’ the issue for a few days, Percy expressed himself in favour. ‘Pupsie is like Migs & likes to make up his mind & face a thing slowly but then definitely for ever! (not like weathercock Wash),’ Mary told Hugo. To her amusement, Percy had seized on the plan as a means of protection ‘against Mumsie’s indiscriminating hospitality’: using Mary to keep ‘away people he don’t like!’ ‘I hope the poor mad sister won’t be forbidden as being bad for Migs i.e. disagreeable for Pup,’ added Mary.21 The ‘poor mad sister’ was Madeline’s sister Mary Carleton. Widowed early, with two small children, Dorothy and Guy, and little money, she was one of Madeline’s many lame ducks. Percy found her intensely annoying.

Throughout the summer Mary had misgivings about Hugo. She knew his inclination for flirting with other women – ‘pairing off with a conk & having long tête-à-tête & purely (or impurely) personal conversations’22 – and feared he was neglecting his Commons’ duties. ‘You see too much of Violet [Manners] & [I] am getting uneasy,’ she told him in early August,23 for Violet, the most artistic of all the Souls women, did not subscribe to the group’s morality in the way Mary’s other friends did. A few weeks later, under pretext of recounting a heated lunchtime debate with Hilda Brodrick and Betty Balfour on J. S. Mill’s Utilitarianism, Mary wrote Hugo a lengthy letter about ‘systematic selfishness’ and the necessity of quelling one’s hedonistic will.24 The subtext was not hard to see.

Mary’s magpie-like, irreverent approach to Mill, twisting his theories to serve her own ends, reflected a frequently criticized trait of the Souls: their alleged want of intellectual depth. When Margot Tennant devised a plan for a Souls’ journal entitled ‘To-morrow: a Women’s journal for men’ (the proposed contents of the first issue included ‘Persons and Politics’ by Margot; the ‘Rise and Fall of Professional Beauties’ by Lady de Grey; ‘Foreign and Colonial Gossip’ by Harry Cust; a short story by Oscar Wilde; a book review by John Addington Symonds and ‘Letters to Men’ by George Wyndham),25 the press pounced on the idea, the News of the World revealing with glee that Webber’s suggested title had been ‘Petticoats’.26 Sir William Harcourt gently mocked the plan: ‘Ah, it is their bodies that I like; and now that they are going to show us their souls all naked in print I shall not care for them.’27 In fact, the journal never came to pass.

By late August, Mary, Hilda and Betty had finished Mill and were planning two days of Butler’s sermons and dissertations before taking the ‘plunge into Sorley’s Ethics of Naturalism, which I hope & trust to have finished before practical Physics in the shape of giving birth to an infant puts a temporary stop to my Ethics – I shall study Physiology first and as intelligence dawns, & the babe looks & smiles at the light, I shall study Psychology combined with jurisprudence & so I shall get back to Ethics again,’ Mary said.28 The other goings-on of the house impinged little upon her. ‘Mr. Adeane’s here (Marie’s brother) rather a muff I think,’ she told Hugo.29

Charles Adeane, whose sister Marie was a maid of honour to the Queen,30 was a twenty-three-year-old Cambridgeshire landowner. He had been courting Mananai since her debut that spring. Of all the sisters, Mananai came closest to replicating their mother’s ‘sweetness and social charm’, without the underlying steel.31 Few were likely to exclaim, as Mananai did, how ‘lovely’ February was as a month, and mean it.32 Her solemn interest in clothes and titles prompted Percy to nickname her ‘Madeline the Mondaine’.33 As a child she had had a tendency to ‘twitch! & wink! Terribly’,34 and despite being older by two years, her development had always noticeably lagged behind the precocious Pamela’s. Like Guy Wyndham, she was a lesser star in the family constellation, but she was passionately supportive of her siblings, championing their achievements and mourning their defeats with utter sincerity, and beloved by them for it.

Mananai found the Souls’ intellectual jousting daunting. Harry Cust earned her lasting affection by confessing to her that he was just as bashful as she: a lie, but a comforting one.35 She felt far more at ease with Charlie Adeane, good-hearted, rather ponderous, apt to pontificate about the problems besetting agriculture, and from a more stolid family of courtiers (although not entirely without spark: Charlie’s jovial uncle Alick, a groom in waiting, had provoked one of the Queen’s most famous comments when he recounted a risqué joke at a state dinner. ‘We are not amused,’36 she replied).

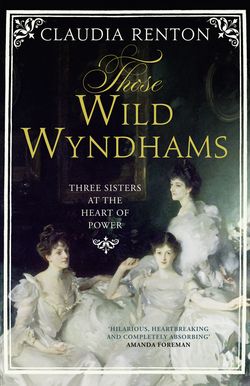

Portrait of Miss Madeline Wyndham, aged sixteen: Mananai on the brink of adulthood, by Edward Burne-Jones.

None of the Wyndhams was particularly impressed by Charlie. Mary and Pamela found the ‘longueurs’ in his conversation a little trying.37 With glee Mary told Hugo that the hapless suitor had tried sounding out Fräulein in confidence about his prospects – a confidence not kept.38 After leaving Clouds, Charlie tried to send Mananai a bracelet as a gift. Madeline Wyndham refused to allow her daughter to accept it. In a friendly but reserved letter, she explained that the Wyndhams thought Mananai too young to marry and did not approve of the five-year age gap between the lovers. Her response was without a shadow of the affection shown to Hugo when he was courting Mary – and he also was five years older than his intended bride.39 Displaying the tolerant good humour that he almost always managed to employ with the Wyndhams, Charlie agreed to make no declaration to Mananai just yet. He asked whether he might send the bracelet to Madeline Wyndham, who could then give it to her daughter; ‘may I say, with my love? … Certainly being in love is not cheerful,’ he added, assuring Madeline that he had read over her letter ‘about fifty times’.40

Madeline Wyndham’s excuses were a pretext. As Souls, it did not matter that Charlie was a Liberal. What mattered was that Charlie’s income, from the Cambridgeshire estate he had inherited upon his alcoholic father’s death, was just £3,000 to £4,000 a year. He could not hope for any more. Given the parlous state of eastern England’s arable estates, he might end up receiving markedly less. As Percy commented, Charlie and any wife of his would not be ‘poor’ but they would not be ‘at all rich’ either.41 Madeline Wyndham thought her charming daughter could do better.

The last weekend of August found the Wyndhams at Clouds with Sibyl Queensberry and her two youngest children, Arthur and Edith Douglas, known respectively as ‘Bosie’ and ‘Wommy’ (the nicknames themselves abbreviations of ‘Boysie’ and ‘Little Woman’), and with Wilfrid Blunt and his teenage daughter Judith. Sibyl and her children frequently visited Clouds, all the more since Sibyl’s acrimonious divorce from the abusive Marquess of Queensberry that year. On Saturday, Arthur Balfour, George Wyndham and Henry James were due to arrive.

In the months since his arrival in Ireland Balfour had shown the Irish – and Westminster – that they had underestimated him. The Unionist policy was to kill Home Rule with kindness, but conciliation went hand in hand with coercion. Balfour made good on his promise to ‘be as relentless as Cromwell in enforcing obedience to the law’.42 Anyone inciting tenants in the rent strike, known as the Plan of Campaign, was immediately imprisoned. Prisoners’ complaints about the putrid conditions in their cells were met with short shrift: the connection between diseased lungs and Irish patriotism was interesting, said Balfour drily.43 By late August, the political world was alight with the news that the Government was putting the Irish MP John Dillon on trial for his part in the Plan of Campaign.

George, erstwhile ‘Fenian’, proud descendant of the Patriot Lord Edward, was now an instrument of one of the most brutally effective periods of repression since the British had crushed the 1798 Rebellion. Yet the Wyndhams managed to reconcile the two. George wanted to save ‘darling Ireland’, as Mary called it,44 and to gain ‘high office’. Quelling agitators could, just about, be interpreted as helping the country reclaim calm. And the Wyndhams were ambitious. They ignored any contradiction, including Madeline Wyndham who while visiting George in Ireland trawled through antique shops, collecting commemorative buttons of the heroes of ’98 to distribute to her children and grandchildren, and requested all family members making the trip to do the same.45 Wilfrid Blunt was resolutely of the opposing view. Ireland was his latest anti-imperialist hobby horse. In 1886, he had visited Ireland and subsequently published in the Pall Mall Gazette, which was under the editorship of the sensationalist journalist W. T. Stead, a devastating exposé of the barbarity of the evictions he found there.46 He now intended to return to Ireland in October to join the fray. He was keenly looking forward to confronting Balfour at Clouds, but by the time Balfour arrived Blunt was already on the back foot, because he had decided that he was in love with Mary: ‘the cleverest best & most beautiful woman in the world with just that touch of human sympathy which brings her to the level of our sins’, he wrote in his diary.47

The family’s reverence for Balfour cast Blunt into a deep gloom. ‘Balfour is here under particularly favourable [circumstances] as he is in love with Mary Elcho, to whom he makes himself of course charming, but, possibly for the same reason, I do not like him much … He has a grand passion for Mary – that is quite clear – and it is equally clear that she has a tendresse for him,’ said Wilfrid as he watched the two, heads bent in conversation, drift off on long walks. ‘But what their exact relations may be I cannot determine. Perhaps it is better not to be too wise, and as all the house accepts the position as the most natural in the world, there let us leave it.’48

It nonetheless made Blunt bad-tempered. No one – except Mary – escaped criticism in his diary. James, ‘always a little behindhand’ in conversation, was disappointing – ‘For a man who writes so lightly and well it is amazing how dull-witted he is.’49 Judith was unacceptably mute at dinner while Pamela and Bosie played boisterous rhyming games. Blunt’s pen was most acidic about Balfour: ‘As a young man he must have been charming and still has some of the ways of a tame cat.’50

On the tennis court, a red-faced and ferocious Blunt, partnering George Wyndham, triumphed over a nonchalant Arthur and Guy Wyndham. That night at dinner, Balfour admitted, to Blunt’s astonishment, that Home Rule was inevitable: that his party’s coercion was merely stalling. ‘When it comes I shall not be sorry,’ Arthur told the assembled party. ‘Only let us have separation as well as Home Rule; England cannot afford to go on with Irishmen in her Parliament. She must govern herself too.’51