Читать книгу Confronting Suburban School Resegregation in California - Clayton A. Hurd - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеCHAPTER 1

White/Latino School Resegregation, the Deprioritization of School Integration, and Prospects for a Future of Shared, High-Quality Education

Latino School Segregation as a Twenty-First-Century Problem

Why, from an equal educational opportunity perspective, should there be any significant concern about the school segregation of Latino youth? What does racial balance have to do with effective, equity-based schooling practice? To understand how Latino school segregation constitutes such a potent challenge to equal educational opportunity in the United States, it is imperative to view the situation beyond a simple “racial balance” issue. In reality, Latino school segregation is systematically linked to other forms of isolation including segregation by socioeconomic status, residential location, and increasingly by language. What has been much less politicized in the integration debate is the class component of segregated schools, that is, the socioeconomic injustice that segregated schools tend to perpetuate, based on the concentrated poverty that is so strongly associated with race in the United States. Unfortunately, Latino segregation almost always involves double or triple segregation, including conditions of concentrated poverty and linguistic separation.

Research statistics from the Civil Rights Project/Proyecto Derechas Civiles at UCLA provide dimension to the problem. Nationally, Latinos are three times more likely than Whites to be in high-poverty schools and twelve times as likely to be in schools where almost everyone is poor (Orfield and Lee 2006). In the western United States, Latinos make up 55 percent of students attending high-poverty schools (defined as schools with 50–100 percent poor students) and 76 percent of those in extreme-poverty schools (defined as 90–100 percent poor students). This is in stark contrast to White students, who represent 26 percent of those in high-poverty schools and only 7 percent of those in extreme-poverty schools. Put another way, 82 percent of White students and only 7 percent of Latinos attend low-poverty schools (20).

In these terms, the problem of Latino school segregation is not a simple psychological burden of racial isolation but a larger syndrome of inequalities related to the double and triple segregation Latino students face in racially isolated schools.1 Latino youth segregated in high-poverty schools—what Orfield and Lee have called “institutions of concentrated disadvantage”—face a host of challenges that impede their access to high-quality K-12 education as well as to college. Students in such schools often face linguistic isolation, with large numbers of native Spanish speakers and few fluent speakers of academic English, which severely limits their opportunities to practice and acquire English, an element considered essential for success in high school, higher education, and beyond (Gándara and Hopkins 2009; Gifford and Valdes 2006). Other significant disadvantages include less contact with teachers credentialed in the subjects they are teaching, a more limited curriculum often taught at less challenging levels, less availability of advanced placement courses that prepare (and sometimes qualify) students for college admission, generally lower levels of parental education, less access to pro-academic peer groups, violence in the form of crime and gangs, dropout problems, lower college-going rates, and lack of proper nutrition and other untreated health problems (Balfanz and Legters 2004; Clotfelter, Ladd, and Vigdor 2005).

In other words, Latino students in racially segregated, high-poverty schools face isolation not only from the White community, but from middle-class schools and the potential benefits derived from them. Low-poverty schools tend to offer stronger academic competition, the ability to attract and hold more qualified instructors teaching in their subject areas, the availability of more accelerated and academically demanding courses, more active involvement of parents, stronger relationships with colleges, better campus facilities and equipment, greater access to pro-academic peer groups, greater access to social networks and experiences that can lead to increased educational and job opportunities, and higher graduation and college-going rates (Betts, Rueben, and Danenberg 2000; Haycock 1998; Orfield 2001).

Beyond the obstacles that confront working-class Latino youth and their families in segregated schooling contexts are the extreme challenges faced by the urban and suburban school systems that serve them. Besides often severe inequalities in school finance due to differential property tax bases, such schools are burdened by added instructional costs related to language training and some forms of special education, constant retraining and supervision of new teachers due to high turnover, frequent student movement and midyear transfers that lead to instability in school enrollments (which also affects consistency of state and federal funding), higher needs for remedial education, increased need for counseling/social work support for students experiencing crises related to living in conditions of poverty, and health emergencies that may arise given many working families’ limited access to preventive care (Orfield and Lee 2005). Taking into account these additional costs, it is clear that even liberal educational reforms aimed at equalizing school funding are likely to fall short, as equal dollars simply cannot produce equal opportunities. From an equity-based schooling perspective, the challenge posed by school segregation is not one of simple racial imbalance, but of the clear disadvantages and burdens faced by students isolated in high-poverty schools versus students who enjoy the relative advantages of low-poverty schools.

A critical question is why, given the tangible and damaging consequences of school segregation to Latino youth, so little attention is given to the current crisis. This is particularly perplexing in the United States, where public opinion has become steadily more supportive of desegregated schools. Since the early 1980s, a vast majority of Americans have tended to endorse desegregation in principle, claiming a philosophical preference for racially integrated schools.2 This popular preference is guided by the wisdom that children must learn how to understand and work with others across differences in order to develop the skills for success in cross-cultural and multiracial work and living environments. In fact, recent longitudinal studies on the experiences of youth who have attended integrated primary and secondary schools point to significant long-term social and career benefits to all students, including improved chances of a desegregated future life, higher educational and occupational aspirations, and an increased likelihood of living and working in interracial settings (Wells 1995; Wells et al. 2009; Yun and Kurlaender 2004; Eaton 2001).

Furthermore, a long-held justification among parents for resistance to integrated schooling—that shared educational environments of this kind cannot be made conducive to high-quality learning for all students—has been challenged by an increasingly rich body of scholarly research identifying a broad range of evidence-based practices that promote effective, shared learning in socioeconomically and racially mixed school settings. This includes development of a variety of curricular models for engaging students in academic learning across politicized social difference (Burris and Welner 2007; Landsman and Lewis 2006; Nieto 2010; Oakes 2005; Pollock 2008) and strategies for socially organizing students within the school and classroom to promote more equal status and engagement in curricular and co-curricular activities (Fine, Weis, and Powel 1997; González, Moll, and Amanti 2005; Hawley 2007; Phelan, Davidson, and Yu 1993; Slavin 1995). Within this literature is a growing body of research that specifically addresses the opportunities and challenges that arise in schooling contexts that bring together working-class Latino populations with middle-class Whites (Cammarota 2007; Conchas 2001; Espinoza- Herold 2003; Gándara 2002; González and Moll 2002; Grady 2002; Mehan et al. 1996; Reyes and Laliberty 1992; Slavin et al. 1996).

If an increasing number of U.S. citizens believe in the potential virtues of integrated schooling—and there are tested, evidence-based models to facilitate learning in such settings—why is school integration in such retreat, and how is it being justified? It would seem important to get at the root of this paradox.

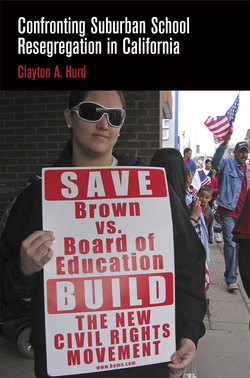

Retreat from Integration and Advancement of School Resegregation in the United States

To date, a broad range of scholarly research has sought to explain the sociohistorical, economic, political, and legal factors that have marred the institutionalization of racial integration as an equity-based school reform strategy in the United States since Brown v. Board of Education. For the purposes of my analysis, I wish to identify and discuss two dominant lines of this inquiry.3 One approach, which I will call the White resistance/deserved segregation framework, relies heavily on macrohistorical analyses of shifting material conditions, race-and class-related interests, and federal court decisions in the twentieth century that have shaped public policy, citizenship narratives, and legal-discursive regimes in manners that have undermined or weakened mandates for school integration and justified a return to more “separate but equal” public schooling conditions. The second, which I will call the normative whiteness/subtractive assimilation framework, pays closer attention to the impact of local-level forces, intergroup relations, and racialization processes and the ways in which they combine to generate the social and institutional conditions that limit school integration efforts on the ground. My discussion here is meant not only to identify how each framework contributes significantly to our understanding of continuing processes of school segregation but also to consider how, by integrating insights from each approach, it may be possible to imagine what a democratic countertendency capable of challenging school resegregation processes might look like. In the final section of this chapter, I draw on the work of Jeannie Oakes and her colleagues to consider how a broad rearticulation of values of fairness and inclusion in the schooling process— spread widely through mobilizations and social movement activism led primarily by working-class communities of color—may have the potential to disarm resegregation campaigns by promoting the idea of shared, high-quality public schooling as a fundamental right of all citizens in the United States. While seemingly far-fetched, such a rearticulation of values and norms was accomplished, on a smaller scale, in a series of Latino-led citizen mobilizations against a ten-year campaign to resegregate local schools in the Pleasanton Valley region of central California, and it is worth considering how such a feat was accomplished and what might be learned from it (the extended case study is offered in Chapter 7).

Suburban Development, White Entitlement and Shifting Discourses of Citizenship in the United States

The White resistance/deserved segregation explanatory approach to the retreat from public school desegregation is perhaps best exemplified in the work of educational scholar Gary Orfield and sociologist George Lipsitz. Each, in separate lines of research, has looked deeply into the political and material histories of race and class in twentieth-century United States that have fueled a process of “refusal, resistance, and renegotiation” (in Lipsitz’s 1998 terms) on the part of residents in predominantly White, middle-class residential communities to avoid a host of federal and state desegregation mandates meant to secure equal access to educational resources and to offer minority students opportunities they have historically been denied (see also Orfield and Eaton 1996). Rather than portraying such political strategies of resistance as predicated on openly racist beliefs, Lipsitz identifies what he calls a “possessive investment in whiteness” whereby “white supremacy is usually less a matter of direct, referential, and snarling contempt than a system for protecting the privileges of whites” (1998: viii) by denying communities of color opportunities for such things as asset accumulation, upward mobility, and—in this case—high-quality integrated education.

To account for the construction of White entitlement in these terms, Lipsitz and others (see, for example, Omi and Winant 1994; Brodkin 1998) have pointed to a key set of twentieth-century politico-historical developments in the United States that have fundamentally reshaped the country’s race/class demographics, political identities, and notions of citizenship in the post-civil rights era. Chief among these developments was the creation and expansion of U.S. residential suburbs from the early twentieth century to the late 1960s as “expressedly racist and exclusionary housing markets” (Lipsitz and Oliver 2010) whose occupation was facilitated, in large part, by federal government-sponsored home loan and mortgage assistantship programs that actively and systematically promoted racial segregation (see also Massey and Denton 1998; Mahoney 1997; Jackson 1985). By condoning racial covenants on the purchase of suburban properties, refusing to lend money to people of color, and colluding with private citizens and local real estate agents in an array of associated discriminatory practices that included racial zoning, redlining, steering, and block busting, the U.S. federal government assured that 98 percent of Federal Housing Act loans disbursed between 1934 and 1968 were provided exclusively to Whites (Lipsitz and Oliver 2010; Roithmayr 2007). Further safeguarding suburban areas as reserved largely for White, middle-class settlement was the prioritized allocation of federal funds for highway construction to the suburbs and the associated financing of urban renewal programs that tended to displace urban minority residents into further racially and socioeconomically segregated living arrangements within metropolitan areas (see Massey and Denton 1997). As Martha Mahoney has remarked, racial segregation and the “Whiteness” of suburbs in the United States are not incidentally paired; “government-sponsored segregation helped inscribe in American culture the equation of ‘good neighborhoods’ with White ones” (1997: 274–75).

U.S. residential suburban areas continued to swell through the mid- to late twentieth century, enhanced significantly in the mid-1960s by processes of “White flight” from metropolitan areas that were increasingly subject to, or threatened by, federal and state school desegregation mandates. Here it is important to note that while the Supreme Court decision in Brown v. Board of Education was handed down in 1954, its broad enforcement remained limited for nearly a decade, and its requirements were generally not assumed to extend beyond the U.S. South. The passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 changed things considerably, as it provided for denial of federal educational funds to school districts continuing to discriminate on the basis of race. It also established the federal Department of Health, Education, and Welfare (HEW) in the Office of Civil Rights, an agency that took the lead in enforcing desegregation by initiating litigation against districts not responding to federal mandates. A string of Supreme Court decisions followed the Civil Rights Act (continuing through the early 1970s) that called for increasingly strict measures for school desegregation, including mandates to extend school integration requirements beyond the U.S. South to western and eastern states, and to expand the right of desegregated schooling to other “protected” minority groups, including Mexican Americans.4

This intensification of federal enforcement for desegregation, along with the extension of minority group entitlements to integrated education, had the effect of generating fervent backlash among segments of the White population in various areas of the country, particularly those who felt dislocated by the economic, political, and cultural shifts they believed to be a product of civil rights strategies.5 The result was massive protests, impassioned political lobbying, and a proliferation of state ballot measures meant to curb or dismantle desegregation efforts, often in open contradiction to federal court decisions in ongoing litigation (Orfield 1997). The ensuing racial-reactive atmosphere fostered the growth of a neoconservative political movement that, incorporating a populist mistrust of “big government” and a distain for the social welfare state, took among its central aims to delegitimize the very civil rights legal framework that had allowed for the conferral of group-based political rights to “protected” racial minorities in the first place. Here, the political intention was to reduce discourses of racial equality and justice from their then-current rootedness in “group rights” principles (a legal recognition hard-earned in the civil rights movement) to largely individual terms—that is, that any individual could be subject to discrimination based on being a victim of the unjust practice of racial preferencing. In other words, the civil rights framework calling for collective equality based on a desirable “equality of result” was to be delegitimized and replaced with one meant to provide a less-specific equality of opportunity for individuals, which could only be achieved through neutral, color-blind policies and strict opposition to any kind of “race thinking” in public policy decision-making.

This reframing of civil-rights-as-individual- rights could find its justification in U.S. liberal democratic principles that have long held group identity and status to be obstacles to the possibility of individual freedom, favored national unity over equality, and viewed the successful American as a self-motivated agent who values a concept of self free from group affiliation and from the past (Schmidt 2000). By intentionally rooting citizenship entitlements in individual rights, those whose wished to roll back the gains of the civil rights movement could present themselves as opponents of both racial discrimination and any antidiscrimination measure based on “group rights” principles—namely, desegregation and affirmative action policies (Omi and Winant 1994: 130).

This powerful populist development, reflected in and amplified by the election of U.S. president Richard Nixon in 1969, led to broad attacks on civil rights strategies, with Nixon himself taking an open and active stance against busing as a means of desegregation, and promising “to restrain HEW’s efforts in the South and to produce a more conservative Justice Department and Supreme Court” (Orfield 1978: 6). Nixon’s appointment of four political conservatives to crucial federal justice positions helped fuel a division in the U.S. Supreme Court regarding its role in directing the desegregation process (Chemerinsky 2003). The Court’s 1974 opinion (5-4) in Milliken v. Bradley reinforced the importance of the “local control” of schools “as essential to both the maintenance of community concern and the support for public schools and to the quality of the educational process,” while its 1977 decision in Dayton Board of Education v. Brinkman (Dayton I) affirmed “local autonomy” with the status of a “vital national tradition . . . long been thought essential both to the maintenance of community concern and the support of public schools and the quality of the educational process” (Bell 1995: 23). By the late 1980s and continuing through the 1990s, the Supreme Court’s rulings on school desegregation more clearly reflected a growing political interest in abandoning the goal of integrating children and moving (back) toward the idea of the “neighborhood school” and arrangements favoring “parental choice.”6 Backing away from hard-fought efforts to push racial integration, federal courts increasingly endorsed “separate but equal” schooling situations, authorizing the diversion of federal desegregation funds from financing integration to enhancing the quality of curriculum at all schools.7

These shifts in school desegregation decision making, and the transformed notions of citizenship they reflected, must also be understood in relation to the extensive suburbanization underway in the late twentieth century, as unprecedented White flight harkened a distinctive transformation in regional politics, particularly in California, where significant political power shifted toward the suburbs. As Ewan McKenzie (1996) has noted, the rise of suburban homeowners associations and other private common interest developments (CIDs) led to the growth of de facto private (residential) government and an increasingly privatized notion of citizenship rights among suburban-dwelling homeowners (see also Kruze 2005; Cashin 2001). Widespread fees levied by residential associations for private services fueled a growing sense of resentment among suburban homeowners for having to “pay more than their share” in allegedly “duplicate” public services, and helped generate a belief that, should they be expected to pay more, it ought to come with the assurance that such spending serve their own interests and not be earmarked for “redistributional” purposes.8 The political legitimacy and justification for such claims of entitlement could be rooted in a longer tradition of U.S. individual rights-based liberalism that assumes the right of citizens, as property owners and taxpayers, to rule their own matters on as local a scale as possible (Lehning 1998).

Under the rubric of “local community control” and through claims of local autonomy, residents of suburban communities were increasingly able to justify utilizing their assets to benefit their own communities and fight for upwardly redistributive policies (and against downwardly redistributive policies) for the expenditure of state and federal funds with little or no reference to the race and class composition of the communities benefiting from these policies (Barlowe 2003).9 This “common sense” suturing of property rights and political rights gained significant traction during the late twentieth century expansion of U.S. suburbanization, as the right to “local control” of public resources and institutions—including public schools—came to be increasingly understood as an entitlement akin to homeownership, merited by virtue of one’s privileged (suburban) residential location and relative socioeconomic status. As McKenzie has argued, the rise of private residential government has helped create a society of suburban homeowners who tend to equate citizen rights with property rights and who seem to share one strong political cause: a near obsessive concern with maintaining or upgrading property values. McKenzie spoke, somewhat prophetically, of a time in which suburban homeowners “may develop an attenuated sense of loyalty and commitment to the public communities in which their CIDs are located, even to the point of virtual or actual secession” (1996: 186). Richard Reich (1991) has called this phenomenon the “secession of the successful,” and Charles Murray warns that it may be the beginning of a new “caste society” in which privatization of local government will lead to a powerful public constituency campaigning to bypass the social institutions they don’t like (quoted in Reich 1991:187).10

Suburban School District “Secessionism” and the Politics of Deserved Segregation

The school district reorganization campaign that is the focus of this study, emerging as it did in the mid-1990s, became immediately known by its opponents as the “Allenstown school district secession campaign.” In my own analysis of the decade-long initiative, I have elected to retain the politicized language of secession because I believe that this campaign—and other citizen-led, suburban school district “reorganization” efforts like it—can be related to other, largely middle-class movements to “secede from responsibility” in a political opportunity structure made possible by the reigning influence of economic neoliberalism, the increase of suburban privatization, and the combined role they have played in reshaping U.S. political and economic life (Boudreau and Keil 2001). Suburban school secession movements, I argue, should be viewed in relation to similar kinds of phenomena emerging not just in the United States, but on a global scale, including territorial secession efforts (like those in Los Angeles in the 1990s) and the increased construction of gated communities and walled cities about which there is an interesting and growing body of ethnographic literature (Caldeira 2000; Lowe 2003; Rivera-Bonilla 1999). What suburban school secession campaigns share with these territorial and community-fortification counterparts is their status as mostly class-based and strongly racialized movements of social separation couched in political terms, that is, articulated in a language of civil rights and liberalism (Boudreau and Keil 2001: 1702). In other words, they tend to use a common set of arguments to justify their actions, including an expressed desire for local control, an expectation of greater return on tax dollars locally, a fear of bureaucracy and big government, and a sense that they, as privileged members of the suburban middle class, are not getting a fair share of what they deserve. Moreover, citizen groups see themselves as fair players, claiming that they—as well as the regions from which they seek separation—will be better off in a “divorce” (1718–19). The populist appeal of citizen-led school district secession campaigns, much like that of their territorial counterparts, is predicated on their ability to frame their arguments in a rhetoric of efficiency and boosterism in ways that effectively capture the imagination of middle-class residents (1723). In the case of school district secessionism, this is done primarily through the promise of an elite, high-quality education as well as liberation from corrupt, unruly school district bureaucracies that fail to prioritize their specific needs and desires.

More difficult to ascertain, from a democratic point of view, is how proponents of school district secessionism find it possible to cast and imagine themselves as fair players despite often compelling empirical evidence that suggests high levels of negative fiscal and educational impact on communities from which they seek separation—communities that, in many cases, are made up of working-class immigrants and people of color. One manner of accounting for such political behavior, as Andrew Barlowe (2003) has argued, is to see it as reflective of contemporary forms of neoliberal, corporate capitalist development and their influence on current social, political, cultural, and economic relationships in the United States. Barlowe’s analysis looks at how a set of neoliberal economic developments in the United States since the 1970s—which have resulted in an acceleration of an income disparity between the rich and the poor; the expansion of nonunionized, parttime, and temporary jobs that provide lower wages and little security; the increased privatization of basic resources like education, health care. and retirement; and the production of a recurring series of economic recessions, including the most recent financial industry bailout—have served to undermine the security of the nation’s middle class (see also Comaroff, Comaroff, and Weller 2001; Harvey 2007, 1991).11 Downward pressures on much of the middle class have provided a context in which the “haves” have taken on an increasingly defensive posture, viewing claims of the “have-nots” on social resources with outright hostility and fear. Moreover, it has allowed a fertile ground for intensification of racism, as middle-class people feel the need to mobilize any and all privileges available to them, including racial privileges, even if they might not recognize them as such, in order to buffer themselves against the fear of downward mobility (Barlowe 2003: 22). In other words, a “fear of falling” has generated a defensive mentality among middle-class citizens, compelling them to exercise social entitlements in ways that increasingly exploit race, class, and national privileges.

While seeking empirical evidence to validate or refute claims about the influence of recent neoliberal economic developments on social, political, and economic behavior is not a central focus of this study, I believe these broader shifts deserve mention for the role they play in providing a political opportunity structure that has facilitated the growth of suburban school secessionism and lent credibility to suburban citizens’ assertions of rights to a separate education rooted in residentially based “local control,” even when the expected outcomes may be unequal access to public resources across lines of both class and race.

Strengths and Limitations of Material-Historical Accounts of the “Failure” of School Integration

The explanatory framework outlined above, with its careful attention to the macro-level demographic, political, and judicial shifts that have limited school integration efforts and normalized privatization over time, proves a useful lens for interpreting the attitudes of entitlement and privilege that some affluent White suburbanites may feel toward their own segregation—an entitlement they have historically achieved in housing but struggle to sustain in schooling, particularly in light of significant growth of ethnoracial diversity in U.S. suburban areas (Frankenberg and Debray 2011; M. Orfield and Luce 2012). Such felt-entitlements can be considered key components of what Stephen Gregory (following W. E. B. Du Bois) has called “wages of whiteness,” a [middle] class struggle through which Whites “evaluate and experience class identity and mobility” as well as engage in a form of antistate and antiminority politics of deserved segregation (1998: 80). In this case, local resistance to integration is rarely voiced in terms of racial or class interests but rather as a (White, middle-class) fear of losing “local control” over the schooling process.

In the present study of the Pleasanton Valley of California, the White resistance/deserved segregation framework proves valuable in accounting for the discourses and behaviors that have come to surround school resegregation efforts. As the extended case studies in the following chapters will attest, parent and civic leaders from the White residential community who have spent nearly a decade pushing for more locally operated (and racially separate) schooling arrangements have framed their struggles primarily as ones meant to sustain the quality of schools, to protect community resources (particularly financial ones), and to maintain local ways of managing their affairs and finances. In this manner, they have achieved significant success in persuading the school board to accept their positions. However, these same residents have also repeatedly mobilized to resist state policies mandating legal rights to Latino children and their families under desegregation laws as well as the forms of social activism, often led by local Mexican-descent citizens, that have attempted to secure those rights (see Chapters 2 and 3). This has included strong opposition to school programs, structures, and practices designed to accommodate Latinos’ native language skills, and to incorporate cultural elements in ways that might make the schools more equally accessible to Latino students and their families (see Chapters 5 and 6). At the same time, local school district board members and senior school site administrators—positions held overwhelmingly by White residents—have continually dismissed allegations that racial, class, and cultural concerns impact how they manage issues of equity and diversity in the district, yet they have nevertheless repeatedly failed to provide leadership in efforts to integrate students and to assure the provision of state-mandated services and resources designed to ensure equal opportunity and services to Latino youth (see Chapter 2). Ultimately, the entitlement that White suburbanites in Pleasanton Valley have felt to their own “quality schools” has meant excluding minority students. In this sense, struggles for segregated schooling conditions in Pleasanton Valley have truly been, in Gregory’s words, a “struggle over what it meant to be white and middle class in postwar, racially segregated American society” (1998: 81).

Yet, even as the White resistance/deserved segregation framework offers essential insights into the macrohistorical conditions that have fueled a retreat from school integration and advanced the growth of suburban school resegregation in the United States, it remains limited as an explanatory model for a number of reasons. One reason is that it fails, in broad terms, to adequately account for the importance of (often hard-fought) “on-the-ground” efforts to develop and institute integration plans at the district and school levels, and how the trajectory of such activities can play a significant role in determining citizens’, parents’, and educators’ attitudes about the viability and desirability of shared schooling. In other words, macro-level accounts tend not to include qualitative and comparative attention to the relative challenges of instituting integration on a school-by-school basis as it relates to curricular and pedagogical development and efforts to facilitate relational cultures and strong partnerships between educators, parents, and school administrators to assure commitment and accountability to educational models that can successfully engage student across racial, class, and linguistic difference (see, for example, strategies highlighted in Warren 2005 and Warren, Mapp, and the Community Organizing School Reform Project 2011).

Another limitation of the dominant White resistance/deserved segregation explanatory framework is that, by privileging processes of White racism and entitlement claims, it tends to obscure the various ways in which historically oppressed racial minority populations have responded to such treatment, denying them any agency outside of victim. Due to this largely unidirectional historical lens, a deep consideration of what school desegregation initiatives have historically expected of racial minority populations has too often been overlooked. As well, little analytical space is given to an exploration of the ways in which racial minority populations may be internally differentiated by various forms of racial, class, and gender-based discrimination, and the consequences of such differentiation on political agency and engagement at local, regional, and national levels (Gilroy 1987; Gregory 1998). Put another way, the explanatory approach, taken alone, fails in broad terms to adequately account for what school desegregation efforts have required of minority groups, and how such expectations have generated conflicts and spawned political subjectivities that have shaped the very terrain on which integration politics, and equity-based school reform debates more broadly, have taken place at local, regional, and national levels.

Normative Whiteness and the Limits of the Integrationist Project Set Forth in Brown

While the White resistance/deserved segregation framework emphasizes the resistance of privileged White citizens to the vision, expectations, and implications of the mandates set forth in Brown v. Board of Education, the fact is that significant voices of critique have also come from within the very minority communities that the Brown ruling was intended to vindicate. These voices of resistance go back to the period before and during the original Brown proceedings when, for example, Black Nationalist leaders spoke strongly against the court’s vision for school integration based on what they regarded as the incomplete understanding of racism and race relations on which the decision was based, and the limited view of racial domination and racial justice that it appeared to reflect (Peller 1996). Because the Brown agenda was framed primarily as a struggle against pathological or psychological manifestations of racist attitudes or behaviors, the court assumed that overcoming prejudice and arriving at racial justice could best be achieved through the social practice of equal treatment. Such a practice would require the establishment of a color-blind position, or a sort of race neutrality within public schools, in which all students would have access to an objectively defined, racially integrated form of “quality education” based on neutral standards of professionalism and universal testing paradigms that could serve as effective and appropriate measures of schooling equality and individual ability (Peller 1996: 131).

What Black Nationalist leaders like Malcolm X and Stokely Carmichael found problematic about this particular framing of the integrationist project was the manner in which it diverted attention away from how race and class backgrounds and experiences have structured socioeconomic, political, and educational opportunities over time, eluding consideration of how racism has operated within a historical context related to centuries of unequal distribution of social, economic, and political opportunities and through normative practices that have served to produce systematic White privilege. Viewing racism as primarily a “problem of psychology” evaded not only issues of class exploitation and struggle but also trivialized and mystified the deeper sources of racial inequality that have never been located solely, or even primarily, in individual actions or prejudices but in a racialized social order sustained through enduring systems of hierarchically organized racial inequality that include de facto occupational, residential, and school segregation (Omi and Winant 1994: 133; see also Lipsitz 1998).12

The Black Nationalist critique of the Brown agenda was not a rejection of integration per se, but a rejection of the particular assimilationist terms under which that integration was expected to take place. Brown promoted a form of integration that was assimilative in nature, based on the dominant paradigm of citizenship and belonging in the United States, which asks all citizens regardless of race, class, or cultural background and experience to assimilate to “American culture” by conforming to normative cultural and linguistic practices, and to concede the use of nonstandard or native linguistic and cultural practices in the public realm. Against the Brown court’s idea that the absence of race consciousness in schools would allow fair, impersonal criteria to inform merit-based decision making and assure “quality education,” the Black Nationalist perspective “characterized the norms that constituted the neutral, impersonal, a-racial, and professional character of school integration as particular cultural assumptions of a specific economic class of Whites” (Peller 1996: 140). In doing so, they sought to deny the very possibility and feasibility of an “ideal,” objective, neutral, and skills-oriented “quality education”; instead, they meant to demystify it as the arbitrary establishment of middle-class, Anglo-American cultural practices and cultural capital as the preferred and rewarded norms of behavior, learning, and interaction within schools (see also Heath 1996; Kelley 1997).13 What was considered dangerous about an approach to desegregated schooling that dismissed as irrelevant—or, at worst, inferior—the cultural and linguistic resources, skills, and experiences of the non-White, non-middle class, was the manner in which it could serve to promote the supposition that cultural deficits explain low achievement, an assumption that was used to justify lowered expectations for working-class racial and ethnic minority students and to encourage disparagement of racial minority group status in ways that have promoted student disengagement from normative educational models (see Foley 1997; McDermott 1997; Valenzuela 1999). The fears articulated by Black Nationalist leaders were that assimilative integration, in practice, would serve as a “subterfuge for White supremacy” (Peller 1996: 139) in which “successfully” desegregated environments would become settings for resegregation due to tracking practices, ability grouping, and expectation of Anglo conformity for equal access, participation, and respect in important schooling activities.

Dangers of White Normativity in Racially and Socioeconomically Diverse Schooling Contexts

Unfortunately, these early concerns about the dangers of assimilative integration have, to a large degree, been realized in public schools in the United States up to the present day. An expansive body of ethnographic literature has been exploring the negative forms and consequences of White normativity in U.S. public schools, including attention to how discourse and practices of “color-blindness” can lead to subtle forms of discrimination and privilege that aid in the production of unequal schooling experiences and outcomes (Kailin 1999; Lewis 2003); how Whiteness can come to function as a status associated with giftedness and privileged entitlement, disproportionally channeling educational resources to White students (Fine 1991; Staiger 2004); and how everyday racialization processes in educational settings can impact student identifications and social affiliations in ways consequential to school success (Bettie 2003; Chesler, Peet, and Sevig 2003; Davidson 1996; Hurd 2008; Olsen 1997; Perry 2002).

This notion of white normativity draws from a more general concept within the social sciences of normative cultural practice, a term that describes a set of dominant expectations, values, principles, and modes of representation that tend to guide interactions within public institutional settings in the United States. Normative whiteness, as Pamela Perry has argued, draws from a set of ideological understandings that, although broadly shared within the population, tend to be linked to particular ways of understanding history, citizenship, notions of self and other, and the very concept of culture itself (2001: 61). The notion of normative whiteness, to paraphrase Margaret Andersen, is less about bodies and skin color than about discursive and material practices that privilege and sustain the dominance of White imperial and middle-class Eurocentric worldviews (2003: 29).

In the United States, two popular discourses underlie practices of White normativity and help account for the damaging forms they may take in racially and socioeconomically diverse schooling contexts, particularly—I will argue—in school settings shared by White and Latino students. The first is that of assimilationist integration which, while typically allowing for some level of public expression of culture and language by ethnic citizens, tends to limit toleration to safe, “folk” genres such as festivals, cultural celebrations, ethnic restaurants, and some forms of media (Baquedano-López 2000; Hill 1999). Strong public expression of cultural and linguistic diversity beyond those contexts—for example, in institutional settings like public schools, workplaces, and voting booths—is often taken to be threatening to national unity and encouraging of ethnic separatism. A second pillar of normative whiteness, which finds justification in the same liberal democratic principles that support the assimilationist perspective, is the racial ideology of color blindness. From a color-blind perspective, the role of multicultural public schooling is to transcend racial consciousness through race neutrality and the social principle of equal treatment, thereby reaffirming the meritocratic idea in U.S. society that economic and social mobility are possible for all those who will work hard and conform to norms and habits of those already in power.

Problems arise in racially and ethnically diverse public schools when these foundational discourses of normative whiteness find themselves at odds with a range of common strategies and practices used by self-proclaimed “multicultural” schools to pursue their inclusive educational missions. These include, for example, racial and cultural pride activities and events, cultural commemorations, ethnic and cultural clubs, and various “ethnic studies” curricular offerings. The result is a certain schizophrenia inherent in many multiracial, socioeconomically diverse schools today, which says that the promotion of multiculturalism is good, but only if it takes noncritical forms that do not interrupt the assimilative function and “neutral” (color-blind) stance of schools. This has justified attacks on anything but the most muted and power-neutral forms of multicultural education, particularly with regard to educational programs designed specifically to address questions of power and status along lines of race, class, and culture. Moreover, wide-ranging reforms like the 2001 No Child Left Behind Act, with their focus on basic skills development, have had the consequence of reinforcing more monocultural, classlocated norms for schooling, as well as condoning a long-standing refusal to acknowledge difference or diversity as a resource. In this manner, even resourceful practices of biculturalism and bilingualism (including code-switching varieties) can be viewed as political challenges or “anti- assmilationist apparatus(es) that challenge the norming process” (Guiterrez, Baquedano-López, and Álvarez 2000: 223). Ultimately, systematic attempts to engage sensitive issues surrounding socioeconomic, racial, or cultural differences in White/Latino shared schooling contexts tend to be vilified as ethnically interested, subversive forms of “victim politics” that promote racial polarization, focus on historical injustices rather than contemporary color-blind conditions, appeal to White guilt, or are motivated by the resentment of Whites (Ovando and McLaren 2000: xix). Moreover, school-based programs that extend beyond the “heroes and holidays” approach to cultural and racial diversity risk being dismissed as “extracurricular” and a distraction from the more “academically rigorous” technical skills training believed to constitute quality education (see Chapter 6 for a case study).

Student Responses to Practices of Normative Whiteness in Schools

Institutional practices of normative whiteness do not, of course, go unchallenged in schools. A long line of student-centered ethnographic research in U.S. public schools has examined the ways in which working-class racial minority youth (including African American, Mexican American, Puerto Rican, and Native American) have employed diverse forms of cultural practice to produce a sense of belonging and solidarity against the White middle-class norms required in the school context (see, for example, Davidson 1996; Foley 1996; Gitlin et al. 2003; Philips 1983). In many cases, such practices take the form of willed resistance against the acquisition of school-valued knowledge, but this is not necessarily the case. Angela Valenzuela (1999), in her study of Mexican American students in a South Texas high school, demonstrates that what would appear to be students’ posture of resistance or “not caring” about school, is actually experienced by them as a sense of ambivalence—a feeling of being caught between a desire to succeed in school, and a level of resignation to the dominant attitudes that marginalize their cultural and linguistic heritage, which they experience as a key element of their group social status (for related analyses, see Davidson 1996; Gibson and Bejínez 2002; Gibson, Gándara, and Koyama 2004; Gitlin et al. 2003; Zentella 1997). In each of these cases, what may appear to be student resistance or academic disengagement may have less to do with an ability or motivation to succeed academically in school than with a desire, as a member of a stigmatized social group, to find a space of equal status among others and to “construct a positive self within and economic and political context which relegates its members to static and disparaged ethnic, racial and class identities” (Zentella 1997: 13).

Collectively, these studies focus on the ways in which unexamined norms of Whiteness and commitments to color-blindness may serve not only to reproduce the school success of middle-class White students in racially mixed school settings but also to actively promote the marginalization of working-class Latino students and discourage their involvement in school contexts that are known to facilitate students’ social integration and academic success, including high-impact co- and extracurricular activities (Davidson 1996; Gibson and Bejínez 2002; Stanton-Salazar, Vásquez, and Mehan 2000). It is in this sense that White normativity can pose a significant and often unacknowledged limit on the effectiveness of educational programs in White/Latino desegregated schooling environments, particularly when student success depends on deep engagement, equal participation, and collaborative learning across what may be significant lines of politicized racial, ethnic, socioeconomic, or gender differences (Fine, Weis, and Powell 1997).

By identifying challenges posed by institutional practices of normative whiteness in racially and socioeconomically diverse school settings, I do not mean to suggest that effective integration is impossible. Instead, I mean to emphasize that the co-location of students in a desegregated setting may do more harm than good if there is not also a strong understanding of, and willingness to address, a broader set of sociocultural and contextual factors—powerfully at play within schools—that mediate student learning, motivation, engagement, and academic success. Ultimately, student learning is a social and political process influenced not only by the school’s formal curriculum and the experiences that students bring into school with them but also by students’ interactions within the school, both with peers and with the staff who organize opportunities for student learning and participation based often on their own (classed, raced, and gendered) assumptions, orientations, and belief systems that often go unacknowledged (Bartolomé and Trueba 2000). In a reframing that challenges popular educational reform logic, Ray McDermott suggests that “instead of asking what individuals learn in school, we should be asking what learning is made possible by social arrangements [within schools] . . . and see differential patterns of academic success along racial lines as an institutionalized, social event rather than a one-by-one failure in psychological development” (1997: 120). McDermott’s admonishment suggests a reimaging of the pursuit for “quality education” from one that seeks to promote a near-exclusive focus on improving classroom instruction to one that seeks to address how schools, as whole institutions, may structure success and failure for particular groups of students (see also Stanton-Salazar, Vásquez, and Mehan 2000).

Hope for a Future of Effective, High-Quality Integrated Education in U.S. Public Schools?

Given the combined reality of rapidly resegregating schools, the deprioritization of integration as an equity-based education reform measure, an escalating desire among affluent residential communities to establish schooling arrangements on their own terms, and the ubiquity of normative practices within desegregated schools that can limit students’ engagement across difference, there would appear to be little room for envisioning how to sustain equitable, high-quality educational environments that could be shared across socioeconomic and racial difference. Yet addressing this challenge would seem all the more timely and critical in light of the rapidly increasing rates of racial and socioeconomic diversity in U.S. suburban areas (M. Orfield and Luce 2012) and the educational injustices that we can expect will be perpetuated if the differential production of low- and high-poverty, racially isolated schools is allowed to continue at pace. Is it feasible, or even possible, to imagine a way to generate the political will to protect and sustain integrated public school contexts and the shared, high-quality, and equitable learning environments they have the potential to provide? If so, from where might such an impetus be likely to come?

In recent writings on equity-based school reform, educational scholar Jeannie Oakes and her colleagues have explored the extent to which grassroots political organizing and activism, led primarily by low-income populations of color, might play a catalytic role in equity-based educational reform in the United States (Oakes et al. 2008; Oakes and Lipton 2002; Rogers and Oakes 2005). Their scholarly project reflects a deeper interest in the possibilities of social movement activism to “win” better schools for working-class Latino and African American communities that have long been the most disadvantaged in terms of access to educational resources, opportunities, and school achievement. Their particular interest in social activism “led primarily by working class communities of color operating largely outside of the educational system” reflects a specific understanding of the primary obstacles to equal educational opportunity in U.S. public schools. This view is that the historical failure to establish high-quality, equitable education in U.S. public schools—despite decades of substantial investment in well-intentioned interventions—is largely the consequence of a long-misguided emphasis in educational reform policy on generating consensus-based, technical solutions to what are primarily normative and political impediments to educational equity (see also Nygreen 2006). In other words, what has long impeded the effectiveness of conventional school reform policy is investment in the faulty assumption that educational problems—including those related to differential achievement—are primarily the consequence of a lack of sufficient knowledge about how to design and implement high-impact teaching practices for diverse learners in ways that support standards-based competencies. As a result, the preferred path of reform has been to focus on programmatic innovations to improve teaching practice and create evidence-based “replicable” programs that, when competently applied, support high-quality learning for all students across (or often in spite of) lines of social difference. Yet decades of educational policy reform in this vein have done remarkably little to disrupt the all-too-familiar patterns of school success and failure across lines of politicized race, class, ethnicity, and gender difference in U.S. schools.

This intractability, Oakes and her colleagues suggest, is better understood as the consequence of normative forces that have long fueled aggressive political opposition to a broad range of equalization efforts designed to improve resources, opportunities, and outcomes on behalf of low-income students of color. These normative forces take the guise of a set of dominant “logics” that define the nation’s thinking about public education (Oakes et al. 2008) and include assumptions about resource scarcity (that the financial resources to support high-quality education are in limited supply); meritocratic privilege (that such limited educational resources ought to be competed for and provided in a privileged manner to those students who are most deserving based on their ability level and preparation, often cast erroneously as their “potential”); and a belief in the existence of unalterable deficits (that low-income students of color face cultural, situational, and individual deficits that schools cannot be expected to alter).

Taken together, these popular logics portray public schooling as a zero-sum game in which opportunities for sought-after high-quality education are in small supply and should be competed for by students, families, and residential communities. When middle-class populations affirm these normative logics, calls for funding to remediate educational inequalities become viewed as an illegitimate redistribution of resources that allegedly “takes away” from the more deserving middle class, provoking fierce resistance to a perceived attack on their “earned” right to transfer educational and socioeconomic opportunities intergenerationally to their children.

A prime example of these normative logics powerfully at play is in the hard-fought (but still largely unfulfilled) effort to institute high-quality integrated education in U.S. public schools. Despite more than fifty years of technical development of effective, evidence-based models for high-quality integrated education, attempts to institutionalize the vision of Brown v. Board of Education have brought “retrogressive action and inertia by elites, anger among nonelite Whites who see themselves as losers in such reform, and disillusionment among excluded groups themselves about the possibility of racial equality and the desirability of racial integration” (Oakes et al. 2008: 2185). The Brown court, by viewing the solution to segregated schools in largely technical terms, failed to fully appreciate the broader socioeconomic conditions, power relations and cultural norms of race, merit, and deficit that have sustained structures of segregation and inequality within public schools and made segregated conditions seem so sensible to those who are privileged by them.

Social Movement Activism as a Potential Subterfuge for Resegregating Schools

This Brown miscalculation, as Derrick Bell (2004: 170) has noted, offers important lessons to advocates of racial justice and equal educational opportunity, suggesting they “rely less on judicial decisions and more on tactics, actions and even attitudes that challenge the continuing assumptions of white dominance.” In Bell’s terms, effective equity-based school reform requires a direct challenge to the dominant cultural norms that have framed debates over “quality education” and the need for advocacy strategies that aim to transform schools away from normative models that have long favored the more affluent, monolingual White middle-class and justified White dominance in educational contexts.

In this sense, social movement activism—particularly when rooted in assertions to high-quality education as a social priority and fundamental right to which all citizens should have an equal entitlement—may have an important role to play (Oakes 1995: 9). Such activism has the potential to succeed where technical, consensus-based reform has not, by addressing in a direct manner the political and normative obstacles to equity-based school reform through efforts to expose, disrupt, and challenge the prevailing logics of public schooling that make segregated schooling conditions appear so normal and unquestionable. As well, social movement activism, and grassroots organizing in particular, can make available political spaces from which to frame, articulate, and establish alternative visions, or critical counternarratives (Villenas and Deyhle 1999; Yasso and Solórzano 2001), capable of shifting the popular meaning of high-quality education from one in which citizens and residential communities are expected to compete for scarce resources toward the idea that high-quality education is essential to human dignity and the civic/economic health of a community without reference to the socioeconomic, cultural, or ethnic backgrounds of its residents (Oakes 1995: 6).

Of course, such a radical reframing of educational rights would require a broad-based political will to fight for inclusive, equitable, and high-quality education that is difficult to imagine, politically, in the current era (Stone et al. 2001). Indeed, as a number of school reform scholars have recently noted, the extent to which such political resolve is possible depends critically on the involvement, leadership, and mobilization of those who are most marginalized and who have the most to lose in the current system and the most to gain in a new one (Fennimore 2004; Noguera 2004; Orfield and Lee 2006).

Such leadership is not unthinkable, however, particularly in light of the increasingly well- documented successes of low-income communities of color to effectively mobilize for stronger school accountability, even in contexts where educational systems have long been controlled by White, middle-class residents and their privilege-protecting interests (see, for example, Noguera 2004; Mediratta, Shaw, and McAlister 2009; Shirley 2002; Warren 2005; and Chapter 7 of this book).

The Mobilization of Latino Communities for Equal Schooling

While relatively little research has been done on the more recent struggles of Mexican American communities to sustain or protect desegregated schools,14 there is a burgeoning literature on Latino political mobilization for school improvement and increased school accountability that is of relevance here. Much of this research has attempted to understand the relative success of Latino mobilizations for school reform in terms of the conceptual framework of social capital (see, for example, Noguera 2004; Shirley 2002; Warren 2005).15 In this work, attention has generally been given to two primary and distinction forms of community capacity-building activities—those related to the creation of bonding, or horizontal social capital—described as the strong and meaningful ties among local, working-class residents of color that can serve as the basis for solidarity and collective, grassroots action—and bridging, or intersectoral social capital, defined as relationships of cooperation and strategic coalition-building between distinct groups, sometimes across lines of significant social difference, where less enfranchised groups are connected to institutions and individuals with access to political influence and money (Fox 1996; Noguera 2004). Examples of positive outcomes associated with bonding social capital have included the mobilization of working-class Latino parents and youth, through intentional processes of leadership development and political education, to serve as school-community liaisons and strong advocates for equal access to such resources as high-quality instruction, fair disciplinary practices and a culturally relevant curricula (see, for example, Delgado-Gaitan 1996; Warren et al. 2011). Successful outcomes associated with bridging or intersectoral social capital building have included such things as the establishment of expansive coalitions linking emergent Latino parent/youth leadership groups with broader civic organizations (e.g., gender, labor, civil, and human rights groups) with a common commitment to issues of equity, fairness, and justice and who collectively undertake school-by-school outreach campaigns to promote and implement more justice-driven, school-based models, programs, and commitments (see Shirley 2002; Warren et al. 2011).16 In each of these cases the process of building power has tended to operate through “organizing groups” that sponsor intentional relationship-building activities, leadership development, political education, and public engagement opportunities in a manner that combines confrontational tactics with strategic efforts at collaboration and institutional development (Warren 2005: 152).17

Notwithstanding these documented successes, it bears recognizing that the mobilization of Latino populations to actively participate in the contentious fight for equal education comes with unique challenges, particularly when it involves immigrant, migrant, and undocumented residents for whom a sense of entitlement to society’s resources may not be easily rooted in national or legal citizenship status. The willingness of Latino (im-)migrant parents and youth to speak up against educational institutions from which they may feel disconnected or alienated can be restricted by a lack of a sense of a “right to have rights” to such basic entitlements as exercising a critical voice in local schooling politics. It is for these reasons that successful campaigns to politically empower U.S. Latinos—particularly Mexican immigrants—have often been rooted in assertions to “cultural citizenship,” that is, rights to belong in the U.S. contingent not on formal citizenship status but on essential human rights to dignity, well-being, and respect (Flores and Benmayor 1997; Rosaldo, Flores, and Silvestrini 1994). Such organizing strategies necessarily engage cultural struggle and power as key elements in the community mobilization process, given the need for strong and collective moral support against ongoing, popular campaigns of exclusion, marginalization, and disenfranchisement (Trueba et al. 1993).18 The importance of organizing around cultural experience and struggle is the context it provides for developing a sense of resiliency and mutual support to collectively navigate cultural, linguistic, and institutional borders in ways that allow residents to participate in community politics with a sense of power and in ways that sustained them as cultural beings (Dyrness 2011).

Educational ethnographers, in partic u lar, have emphasized the importance of such strategies for empowering immigrant Latina/o parents to become active participants in schooling politics, including the need to create spaces for parents to tell their stories and engage in a political process of “becoming and belonging,” which allows them to meet their own goals of self-realization and transformation rather than expecting them to simply “get involved” in existing school site activities that may be perceived as hostile or alienating (Dyrness 2008: 193; see also Delgado-Gaitan 1996; Villenas 2001; Villenas and Deyhle 1999). The availability of such relatively segregated “safe spaces”19— often favorably located outside formal institutional settings where normative forces of class/race privilege and entitlement can limit critical conversations—allows a context for socially and politically marginalized citizens to engage in a process of mutual dialogue that may include examining experiences of oppression, cultivating a critical awareness of the larger political system in which their lives are located along with the skills and voice to participate in it, and developing new leadership skills, knowledge, and aspirations, “as well as norms of collective deliberation that enable communities to mobilize social capital for shared goals” (Mediratta, Shah, and McAlister 2009: 140). As organizing contexts, such spaces allow room for Latino participants to understand power, learn public speaking and organizing skills, and “collectively create counter-hegemonic narratives of dignity and cultural pride” that contest the normative societal discourses of deficiency and lack by which their communities and children are often defined (Villenas and Deyhle 1999: 437; Foley 1997),20 and permit a questioning and reframing of the prevalent logics of educational merit and entitlement that have tended historically to distribute high-quality schooling experiences and opportunities differentially and unequally along lines of race, class, and culture.

Challenges to School Reform Or ganizing for Integrated Education

A distinct challenge for organizing efforts aimed specifically at protecting high-quality integrated education is that even with substantial capacity building and mobilization of residents from within working-class Latino communities, success is unlikely without support from a significant cross-section of residents from White middle-class communities as well. The prospect of enlisting significant support from White middle-class residents relies on the existence of widely shared convictions about the usefulness and viability of integrated schooling, including a belief among parents that they are not being asked to choose between “diversity” and “excellence” because there are compelling academic and social benefits associated with integrated education (Orfield, Frankenberg, and Siegel-Hawley 2010). From a grassroots mobilization perspective, it requires the ability to craft a collective action frame broad enough to permit a shared understanding of high-quality, integrated education as both a desirable option (rather than a threatening imposition) and a moral imperative (Oakes and Lipton 2002), so as to attract a critical mass of middle-class White parents as well.

Yet the task of establishing and then sustaining such a social movement frame is difficult when conflict, contention, and cultural struggle are taken as important crucibles for building power and civic capacity for educational change (as they have been with Latino school reform organizing efforts), and when the focus of activity is to challenge normative logics that have long favored affluent White suburbanites. Despite such obstacles, however, organizing in support of shared, high-quality schooling is possible, as Chapter 7 will explore. Here, Latino-led groups in Pleasanton Valley successfully built a broad-based collective action frame that portrayed high-quality integrated education as a fundamental right for all citizens, suggesting there is still some hope for establishing a level of political will sufficient to support integrated schools. Whether or not such popular will can be sustained and translated into structural change at the district and school site levels—against existent political and normative forces of resistance and in a way that sustains a critical mass of supporters from the White residential community—remains to be seen.

Summary

In this chapter, I have tried to account for how processes of school resegregation are occurring despite the nation’s commitment in principle to racial and socioeconomic justice, equal citizenship, and equal opportunity in the educational realm. Ultimately, school segregation remains a significant barrier to equal educational opportunity not because of some intangible psychological burden, but because of the way in which it isolates whole communities of color in “schools of concentrated disadvantage” for which even campaigns to equalize school funding and enhance teacher training can be expected to have limited impact. Nevertheless, there is a clear divestment in school integration as an equity-based reform measure in the United States, due in significant part to the sustained influence of a particular set of normative assumptions about the “nature” of educational problems in public schools and how they should best be resolved. These assumptions fail, in general, to appreciate the importance of social, economic, and political contexts on students’ learning process; instead, they portray “multicultural” schools in the United States as largely neutral institutions that provide equal opportunity for all through a technical, skills-based literacy program that assesses student performance based on very specific (and limited) understandings of what constitutes—and indeed, permits—educational success for diverse learners. The hegemonic assumptions underlying current schooling policy and practice have served to further condone a refusal to view linguistic, cultural, and class experiences as important resources to be engaged in the educational process, reducing them instead to explanations of why students fail.

The retreat from integration and the growth of school resegregation in U.S. suburban areas is not, of course, a simple product of shifting educational discourses; there are clear material interests at play. The ability of White, middle-class suburban residents to renegotiate the terms and possibilities of shared schooling has been made increasingly possible by the prevalent neoliberalism and the growth of an increasingly suburbanized and privatized nation-state.

I would argue, nevertheless, that there is some reason for hope about the future of shared, high-quality education, but only if equity-based school reform efforts can move beyond a primary focus on technical innovations within schools and classrooms—for example, the creation of new, more inclusive educational curricular programs and enhancements of teacher training—to encompass more popular efforts to “confront the non-technical (social, political, cultural) dimensions of change that must occur within our schools and across society before the promise of Brown can be fulfilled” (Rogers and Oakes 2005: 2195). To this end, social movement activism provides a promising route, particularly when organizing energy and network building is put toward developing and articulating alternative visions of entitlement to “quality education” that challenge the highly normative assumptions and processes that make conditions of segregation so unquestioned within our current educational system. Establishing and sustaining the political will to pursue and put into practice such alternative visions will likely rely heavily on the leadership of working-class communities of color who have the most to lose in the current system and the most to gain in a new one.

The discussion in this chapter, while providing a broad context for understanding the proliferation of citizen-led school secession campaigns, does not fully account for the manner in which such campaigns take root and find justification locally. School resegregation campaigns are, ultimately, local and regional productions that take shape in relation to specific histories of social group encounters, and the impact of these encounters on the development of schooling practices, structures, and patterns of engagement in schooling politics. This local/regional historical process is the focus of the next chapter, as I introduce cultural politics of place and schooling in Pleasanton Valley.