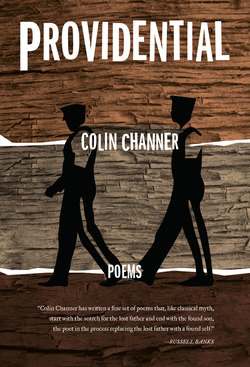

Читать книгу Providential - Colin Channer - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеMIMIC

I.

From the chopper shot

the beach is a golden border

on a brown-gray shack town,

a jumble on a point,

sweet flourish of Liberia

sweeping into waves.

My son and I are watching

this in lamplight from our low

brown armless couch,

iced roibos on the low wood table

where I keep a bowl of beat-up cricket balls,

a wink to where he indirectly comes from,

Makonnen, Brooklyn teenager

with Antillean roots

replanted in Rhode Island,

a state petiter than the country

where my navel string was cut.

He’s a boy who loves sketching,

drawing cartoons, eating fish and pasta,

swimming, but most of all

performing accents, likes how

they jokify the mouth.

He was born with the ears of a mimic,

a tight connect between what makes a sound

and how to counterfeit it, make it feel

authentic near its place of birth.

On screen, the camera jerks

behind an ex-warlord

up chipped-up stairs

to a big slab roof.

Here, he’s questioned by

a pink and meaty hipster,

dude keen to talk to men

who say they ate their foes in war.

This one here refers

to chopping wide the backs of children,

mimes reaching in the crack

to pluck a heart,

and munching it before a fight

for blood and courage,

naked at times, or done drag,

boots with wigs and dresses,

amulets and other charms,

the more bizarre

the better hidden.

Spirits can evade

the human eye.

Maki echoes all the interviewer’s

LA nasals. I laugh hard.

But when he takes on

a Liberian accent

I do not take it well

although I’m twisted

by the sketch, a poly-vocal

back-and-forth involving riots.

It’s peacetime and we’re at

Monrovia’s first McDonald’s.

Folks are vexed.

The burgers aren’t made

from human flesh.

I gently tell him he,

well, we shouldn’t joke too much

about this awful war,

and blah blah on about this country

founded on the coast of Guinea

by ex-chattel,

guide him through the marsh

of history to the present,

leading as a father should a son.

II.

Later, as I pinch out

contact lenses, my own voice

comes blah-blah-ing

from behind the mirror mounted

to the bathroom wall.

I smile at Mr. Silly’s talents,

how he switches accents

from Liberian to mine,

hacking vowels,

pitching consonants

precisely in the mouth,

beginning now another improv,

phone calls from police headquarters

in Gbarnga, begging Kingston

for assistance, tips for getting info

out of infants who

despite receiving torture

still refuse to talk.

In my bed, on light cotton,

ceiling fan on slow,

I miscue the iPod in the dock.

Callas, not Lee Perry, comes on.

In my head I talk to Maki

and myself.

The confessors are clan

to killers on an island

I know. Same nose,

same eyes, same trail of razor

bumping on the shine-

clean cheeks. The nicknames

from the news and movies.

Rambo, bin Laden.

The loafers, designer jeans

and polo shirts worn loose.

How they discuss a slaughter

with ease, by rote,

never as something spectacular,

absurd. And I belong to them,

on two sides, for generations,

by blood.

My kinsmen aren’t poets.

They’re cops.