Читать книгу Providential - Colin Channer - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеLEA

I.

They played coc’nut bough

cricket in the growing season,

attended school half time,

otherwise worked with grown-ups,

cutting, ratooning, drawing water

from the spring that drove the wheel.

Thirty years, a generation plus

from slavery, and Lea,

my mother’s great-grandad

and Nev, his closest friend,

were living mostly in their

great-grandparents’ world,

one of long views to far hills,

but tight boundaries,

force and sense and habit

keeping people in their place.

When militias killed a thousand blacks

out in St. Thomas back in 1865,

put on that famous vigilante pageant

that began with muskets firing

on protesters in a courthouse square,

my mother’s great-grandfather was a child.

Still, busha called him for his labor,

told him to get Nev,

made him lead on his pardy,

to the lignum vitae woods

to work with grown survivors

heaving corpses into graves.

Imagine that boy, his friend and other children

massed on the bank of a hole,

handling bodies,

lifting, passing, easing down,

the cadence like the one employed

to pack ox carts with hogsheads,

barrels of molasses. Spitting ashes.

Coughing dust.

Now, follow born-free and ex-chattel,

going home at twilight, slow marching,

dressed in rag calico, burlap, osnaburg,

using footbeat to hold a rhythm,

no talking, passing burnt houses,

cottages hit down, then seeing up ahead

odd statues

cast in shadow, set in bush—

no, folks grief struck,

heads down.

Now to this moment add rain.

II.

It’s a detail Lea included

when he told the tale

to Phyllis Fay,

his great-grandchild, my mum,

who asked about a photo

framed in pewter on a bureau

in the bungalow he lived in

on a farm in St. Ann,

way, way far from St. Thomas,

beyond a watershed,

decent acreage in Gibraltar

hamlet in low hills,

all small holdings,

good people, stone fences,

woods lush with bamboo,

and fat white cows.

It rained for days he told her,

like Bible,

and the whole place smelled of war,

and ’cause everything was broke up

they slept for days in mud

until, thanks be to God, sunshine came back slowly,

and things took time to dry out, and life—

well, it went back to normal,

to duties and habits,

same difference, old usual,

scratching dirt, doing what you do

as ’cording to what season,

planting, reaping—

if busha don’t need you—maybe little school.

That’s how it was—

you worked as you should,

kept your mind on now,

left behind whatever happened—

as they learned you

with the switch from early—

what to keep, and what to talk.

And so it was. Forgotten.

There, but as a dust of disquiet,

a fog of unease until that first Easter

after martial law when he and Neville,

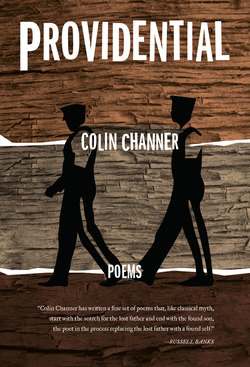

same Inspector Bledsoe in the photo,

sneaked away to idle,

hunt birds and play cricket in a clearing

near some cedar woods

and corpses started poking from the ground.

From that day,

he told his great-grandchild,

he could see things, cross over and come back,

and that’s how he earned a shilling—

selling conference with the dead,

finding well water,

susu-ing what to seed in what season,

when drought would come.

For those he loved

he drew tonics, brewed infusions,

stood as surety for loans,

sat on his porch in Gibraltar,

gave advice in his hat and jacket,

healed with tea and words,

patient with the lines,

sloe eyes blankish,

then took to bed with john crow batty,

crude white rum, sometimes two bottles,

and think and think and think about the killings,

drift to the slaughter

and the what came next,

the digging, the heaving, the

hiding with dirt,

but most of all how quickly

he and Neville took to acting normal,

went back to simple pickney life.