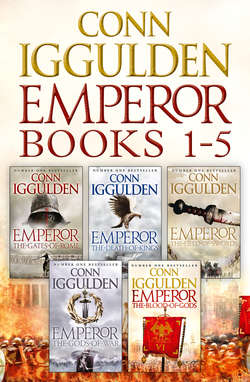

Читать книгу The Emperor Series Books 1-5 - Conn Iggulden - Страница 13

CHAPTER FOUR

ОглавлениеThe circus was arranged by Cornelius Sulla, a rising young man in the ranks of Roman society. The king of Mauretania had entertained the young senator while he commanded the Second Alaudae legion in Africa. To please him, King Bocchus sent a hundred lions and twenty of his best spearmen to the capital. With these as a core, Sulla had put together a programme for five days of trials and excitement.

It was to be the largest circus ever arranged in Rome and Cornelius Sulla had his reputation and status assured by the achievement. There were even calls raised in Senate for there to be a more permanent structure to hold the games. The wooden benches bolted and pegged together for great events were unsatisfactory and really too small for the sort of crowds that wanted to see lions from the dark, unknown continent. Plans for a vast circular amphitheatre capable of holding water and staging sea battles were put forward, but the cost was huge and they were vetoed by the people’s tribunes as a matter of course.

Gaius and Marcus trotted behind the two older men. Since Gaius’ mother had become unwell, the boys were rarely allowed into the city proper any more, as she fretted and rocked in misery at the thought of what could happen to her son in the vicious streets. The noise of the crowd was like a blow and their eyes were bright with interest.

Most of the Senate would travel to the games in carriages, pulled or carried by slaves and horses. Gaius’ father scorned this and chose to walk through the crowds. That said, the imposing figure of Tubruk beside him, fully armed as he was, kept the plebeians from shoving too rudely.

The mud of the narrow streets had been churned into a stinking broth by the huge throng and after only a short time their legs were spattered almost to the knees by filth, their sandals covered. Every shop heaved with people as they passed and there was always a crowd ahead and a mob behind pushing them on. Occasionally, Gaius’ father would take side streets when the roads were blocked completely by shopkeepers’ carts carrying their wares around the city. These were packed with the poor, and beggars sat in doorways, blind and maimed, with their hands outstretched. The brick buildings loomed over them, five and six storeys high, and, once, Tubruk put a hand out to hold Marcus back as a bucket of slops was poured out of an open window into the street below.

Gaius’ father looked grim, but walked on without stopping, his sense of direction bringing them through the dark maze back onto the main streets to the circus. The noise of the city intensified as they grew close, with the shouted cries of hot-food sellers competing with the hammering of coppersmiths and bawling, screaming children who hung, snot-nosed, on their mothers’ hips.

On every street corner, jugglers and conjurors, clowns and snake charmers performed for thrown coins. That day, the pickings were slim, despite the huge crowds. Why waste your money on things you could see every day when the amphitheatre was open?

‘Stay close to us,’ Tubruk said, bringing the boys’ attention back from the colours, smells and noise. He laughed at their wide-mouthed expressions. ‘I remember the first time I saw a circus – the Vespia, where I was to fight my first battle, untrained and slow, just a slave with a sword.’

‘You won, though,’ Julius replied, smiling as they walked.

‘My stomach was playing me up, so I was in a terrible mood.’

Both men laughed.

‘I’d hate to face a lion,’ Tubruk continued. ‘I’ve seen a couple on the loose in Africa. They move like horses at the charge when they want to, but with fangs and claws like iron nails.’

‘They have a hundred of the beasts and two shows a day for five days, so we should see ten of them against a selection of fighters. I am looking forward to seeing these black spearmen in action. It will be interesting to see if they can match our javelin throwers for accuracy.’

They walked under the entrance arch and paused at a series of wooden tubs filled with water. For a small coin, they had the mud and smell scrubbed from their legs and sandals. It was good to be clean again. With the help of an attendant, they found the seats reserved for them by one of the estate slaves, who’d travelled in the previous evening to await their arrival. Once they were seated, the slave stood to walk the miles back to the estate. Tubruk passed him another coin to buy food for the journey and the man smiled cheerfully, pleased to be away from the backbreaking labour of the fields for once.

All around them sat the members of the patrician families and their slaves. Although there were only three hundred representatives in the Senate, there must have been close to a thousand others. Rome’s lawmakers had taken the day off for the first battles of the five-day run. The sand was raked smooth in the vast pit; the wooden stands filled with thirty thousand of the classes of Rome. The morning heat built and built into a wall of discomfort, largely ignored by the people.

‘Where are the fighters, Father?’ Gaius asked, searching for signs of lions or cages.

‘They are in that barn building over there. You see where the gates are? There.’

He opened a folded programme, purchased from a slave as they went in.

‘The organiser of the games will welcome us and probably thank Cornelius Sulla. We will all cheer for Sulla’s cleverness in making such a spectacle possible. Then there are four gladiatorial combats, to first blood only. One will follow that is to the death. Renius will give a demonstration of some sort and then the lions will roam “the landscapes of their Africa”, whatever that means. Should be an impressive show.’

‘Have you ever seen a lion?’

‘Once, in the zoo. I have never fought one, though. Tubruk says they are fearsome in battle.’

The amphitheatre fell quiet as the gates opened and a man walked out dressed in a toga so white it almost glowed.

‘He looks like a god,’ Marcus whispered.

Tubruk leaned over to the boy. ‘Don’t forget they bleach the cloth with human urine. There’s a lesson in there somewhere.’

Marcus looked at Tubruk in surprise for a moment, wondering if a joke had been made of some kind. Then he forgot about it as he tried to hear the voice of the man who had strode to the centre of the sand. He had a trained voice, and the bowl of the amphitheatre acted as a perfect reflector. Nonetheless, part of his announcement was lost as people shuffled or whispered to their friends and were shushed.

‘… welcome that is due … African beasts … Cornelius Sulla!’

The last was said in crescendo and the audience cheered dutifully, more enthusiastically than Julius or Tubruk had been expecting. Gaius heard the words of the old gladiator as he leaned in close to his father.

‘He may be a man to watch, this one.’

‘Or to watch out for,’ his father replied with a meaningful look.

Gaius strained to see the man who rose from his seat and bowed. He too wore a simple toga, with an embroidered hem of gold. He was sitting close enough for Gaius to see this really was a man who looked like a god. He had a strong, handsome face and golden skin. He waved and sat down, smiling at the pleasure of the crowds.

Everyone settled back for the main excitement, conversations springing up all around. Politics and finance were discussed. Cases being argued in law were raked and chewed over by the patricians. They were still the ultimate power in Rome and therefore the world. True, the people’s tribunes, with their right to veto agreements, had taken some of the edge off their authority, but they still had the power of life and death over most of the citizens of Rome.

The first pair of fighters entered wearing tunics of blue and black. Neither was heavily armoured, as this was a display of speed and skill rather than savagery. Men did die in these contests, but it was rare. After a salute to the organiser and sponsor of the games, they began to move, short swords held rigid and shields moving in hypnotic rhythms.

‘Who will win, Tubruk?’ Gaius’ father suddenly snapped.

‘The smaller, in the blue. His footwork is excellent.’

Julius summoned one of the runners for the circus betting groups and gave over a gold aureus coin, receiving a tiny blue plaque in return. Less than a minute later, the smaller man side-stepped an over-extended lunge and drew his knife lightly over the other’s stomach as he stepped through. Blood spilled as over the lip of a cup and the audience erupted with cheers and curses. Julius had earned two aurei for the one he’d wagered and he pocketed the profit cheerfully. For each match that followed, he would ask Tubruk who would win as they began to feint and move. The odds sank after the start, of course, but Tubruk’s eye was infallible that day. By the fourth match, all nearby spectators were craning to catch what Tubruk said and then shouting for the betting slaves to take their money.

Tubruk was enjoying himself.

‘This next one is to the death. The odds favour the Corinthian fighter, Alexandros. He has never been stopped, but his opponent, from the south of Italy, is also fearful and has never been beaten to first blood. I cannot choose between them at this point.’

‘Let me know as soon as you can. I have ten aurei ready for the wager – all our winnings and my original stakes. Your eye is perfect today.’

Julius summoned the betting slave and told him to stand close. No one else in the area wanted to bet, as they all felt the luck of the moment and were content to wait for the signal from Tubruk. They watched him, some with held breath, poised for the first signal.

Gaius and Marcus looked at the crowd.

‘They are a greedy lot, these Romans,’ Gaius whispered and they grinned at each other.

The gates opened again and Alexandros and Enzo entered. The Roman, Enzo, wore a standard set of mail covering his right arm from hand to neck and a brass helmet above the darker iron scales. He carried a red shield in his left. His only other garments were a loincloth and wrappings of linen around his feet and ankles. He had a powerful physique and carried few scars, although one puckered line marked his left forearm from wrist to elbow. He bowed to Cornelius Sulla and saluted the crowd first, before the foreigner.

Alexandros moved well, balanced and assured as he came to the middle of the amphitheatre. He was identically dressed, although his shield was stained blue.

‘They are not easy to tell apart,’ Gaius said. ‘In the armour, they could be brothers.’

His father snorted. ‘Except for the blood in them. The Greek is not the same as the Italian. He has different and false gods. He believes things that no decent Roman would ever stand for.’ He spoke without turning his head, intent on the men below.

‘But will you bet on such a man?’ Gaius continued.

‘I will if Tubruk thinks he will win,’ came the response, accompanied by a smile.

The contest would begin with the sounding of a ram’s horn. It was held in copper jaws in the first row of seats and a short bearded man was waiting for his own signal to set his lips to it. The two gladiators stepped close to each other and the horn sound wailed out across the sand.

Before Gaius could tell whether the sound had stopped, the crowd was roaring and the two men were hammering blows at each other. In the first few seconds, strike after strike landed, some cutting, some sliding from steel made suddenly slippery with bright blood.

‘Tubruk?’ came his father’s voice.

Their area of the stands was torn between watching the fantastic display of savagery and getting in on the bet.

Tubruk frowned, his chin on his bunched fist.

‘Not yet. I cannot tell. They are too even.’

The two men broke apart for a moment, unable to keep up the pace of the first minute. Both were bleeding and both were spattered with dust sticking to their sweat.

Alexandros rammed his blue shield up under the other’s guard, breaking his rhythm and balance. His sword arm came up and over, looking for a high wound. The Italian scrambled back without dignity to escape the blow and his shield fell in the dust as he did so. The crowd hooted and jeered, embarrassed by their man. He rose again and attacked, perhaps stung by the comments of his countrymen.

‘Tubruk?’ Julius laid his hand on the man’s arm. The fight could be over in seconds and if there was an obvious advantage to one of the fighters, the betting would cease.

‘Not yet. Not … yet …’ Tubruk was a study in concentration.

On the sand, the area around the fighters was speckled darkly where their blood had dripped. Both paced to the left and then the right, then rushed in and cut and sliced, ducked and blocked, punched and tried to trip the other. Alexandros caught the Italian’s sword on his shield. It was partially destroyed in the force of the blow and the blade was trapped by the softer metal of the blue rectangle. Like the other, it too was wrenched to the sand and both men faced each other sideways on, moving like crabs so that their arm-mail would protect them. The swords were nicked and blunted and the exertions in the raging Roman heat were beginning to tell on their strength.

‘Put it all on the Greek, quickly,’ Tubruk spoke.

The betting slave looked for approval to the owner behind him. Odds were whispered and the bets went on, with much of the crowd taking a slice.

‘Five to one against on Alexandros – could have been a lot better if we’d gone earlier,’ Julius muttered, as he watched the two fighters below.

Tubruk said nothing.

One of the gladiators lunged and recovered too fast for the other. The sword whipped back and into his side, causing a gout of blood to rush. The riposte was viciously fast and sliced through a major leg muscle. A leg buckled and as the man went down, his opponent hacked into his neck, over and over, until he was thumping at a corpse. He lay in the mixing blood, as it was sucked away by the dry sand and his chest heaved with the pain and exertion.

‘Who won?’ Gaius asked frantically. Without the shields it wasn’t clear, and a murmur went around the seats as the question was repeated over and over. Who had won?

‘I think the Greek is dead,’ the betting slave said.

His master thought it was the Roman, but until the victor rose and removed his helmet, no one could be sure.

‘What happens if they both die?’ Marcus asked.

‘All bets are off,’ replied the owner and financier of the betting slave. Presumably he had a lot of money riding on the outcome as well. Certainly he looked as tense as anyone there.

For maybe a minute, the surviving gladiator lay exhausted, his blood spilling. The crowd grew louder, calling on him to rise and take off the helmet. Slowly, in obvious pain, he grasped his sword and pushed himself up on it. Standing, he swayed slightly and reached down to take a handful of sand. He rubbed the sand into his wound, watching as it fell away in soft red clumps. His fingers too were bloody as he raised them to remove the helmet.

Alexandros the Greek stood and smiled, his face pale with loss of blood. The crowd threw abuse at the swaying figure. Coins glittered in the sun as they were thrown, not to reward, but to hurt. With curses, money was exchanged all around the amphitheatre and the gladiator was ignored as he sank to his knees again and had to be helped out by slaves.

Tubruk watched him go, his face unreadable.

‘Is he a man to see about training?’ Julius asked, ebullient as his winnings were counted into a pouch.

‘No – he won’t last out the week, I should think. Anyway, there was little schooling in his technique, just good speed and reflexes.’

‘For a Greek,’ said Marcus, trying to join in.

‘Yes, good reflexes for a Greek,’ Tubruk replied, his mind far away.

While the sand was being raked clean, the crowd continued with their business, although Gaius and Marcus could see one or two spectators re-enacting the gladiators’ blows with shouts and mock cries of pain. As they waited, the boys saw Julius tap Tubruk on his arm, bringing to his attention a pair of men approaching through the rows. Both seemed slightly out of place at the circus, with their togas of rough wool and their skins unadorned by metal jewellery.

Julius stood with Tubruk and the boys copied them. Gaius’ father put out his hand and greeted the first to reach them, who bowed his head slightly on contact.

‘Greetings, my friends. Please take a seat. This is my son and another boy in my care. I’m sure they can spend a few minutes buying food?’

Tubruk handed a coin to both of them and the message was clear. Reluctantly, they moved off between the rows and joined a queue at a food stall. They watched as the four men bent their heads close and talked, their voices lost in the crowd.

After a few minutes, as Marcus was buying oranges, Gaius saw the two newcomers thank his father and take his hand again. Then each moved over to Tubruk, who put coins in their hands as they left.

Marcus had bought an orange for each of them and when they’d returned to their seats he handed them out.

‘Who were those men, Father?’ Gaius asked, intrigued.

‘Clients of mine. I have a few bound to me in the city,’ Julius replied, skinning his orange neatly.

‘But what do they do? I have never seen them before.’

Julius turned to his son, registering the interest. He smiled.

‘They are useful men. They vote for candidates I support, or guard me in dangerous areas. They carry messages for me, or … a thousand other small things. In return, they get six denarii a day, each man.’

Marcus whistled. ‘That must add up to a fortune.’

Julius transferred his attention to Marcus, who dropped his gaze and fiddled with the skin of his orange.

‘Money well spent. In this city, it is good to have men I can call on quickly, for any sudden task. Rich members of the Senate may have hundreds of clients. It is part of our system.’

‘Can you trust these clients of yours?’ Gaius broke in.

Julius grunted. ‘Not with anything worth more than six denarii a day.’

Renius entered without announcement. One moment, the crowd were chatting amongst themselves with the dirty sand ring empty, and the next a small door opened and a man walked out of it. At first, he wasn’t noticed, then people pointed and began to stand.

‘Why are they cheering so loudly?’ Marcus asked, squinting at the lone figure standing in the burning sun.

‘Because he has come back one more time. Now you will be able to say you saw Renius fight when you have children of your own,’ Tubruk replied, smiling.

Everyone around them seemed lit up by the spectacle. A chant began and swelled: ‘Ren-i-us … Ren-i-us.’ The noise drowned out all the shuffling of feet and rustling clothing. The only sound in the world was his name.

He raised his sword in salute. Even from a distance, it was clear that age had not yet taken a good twisting grip on him.

‘Looks good for sixty. Belly’s not flat, though. Look at that wide belt,’ Tubruk muttered almost to himself. ‘You’ve let yourself go a little, you silly old fool.’

As the old man received the plaudits of the crowd, a single file of fighting slaves entered the sandy ring. Each wore a cloth around his loins that allowed free movement and carried a short gladius. No shields or armour could be seen. The Roman crowd fell quiet as the men formed a diamond with Renius at the centre. There was a moment of stillness and then the animal enclosure opened.

Even before the cage was dragged out onto the sand, the short, hacking roars could be heard. The crowd whispered in anticipation. There were three lions pacing the cage as it was dragged out by sweating slaves. Through the bars they were obscene shapes; huge humped shoulders, head and jaws tapering back to hindquarters almost as an afterthought. They were created to crush out life with massive jaws. They swiped with their paws in unfocused rage as the cage was jarred and finally came to rest.

Slaves lifted hammers aloft to knock out the wooden pegs that held the front section of the cage. The crowd licked dry lips. The hammers fell, and the iron lattice dropped onto the sand, an echo clearly heard in the silence. One by one, the great cats moved out of the cage, revealing a speed and sureness of step that was frightening.

The largest roared defiance at the group of men that faced it across the sand. When they made no move, it began to pace up and down outside the cage, watching them all the while. Its companions roared and circled and it settled back onto its haunches.

Without a signal, without a warning, it ran at the men, who shrank back visibly. This was death coming for them.

Renius could be heard barking out commands. The front of the diamond, three brave men, met the charge, swords ready. At the last moment, the lion took off in a rushing leap and smashed two of the slaves from their feet, striking with a paw on each chest. Neither moved, as their chests were shards and daggers of bone. The third man swung and hit the heavy mane, doing little damage. The jaws closed on his arm in a snap like the strike of a snake. He screamed and carried on screaming as he staggered away, one wrist holding the pumping red remains of the other. A sword scraped along the lion’s ribs and another cut a hamstring so that the rear quarters went suddenly limp. This served only to enrage the beast and it snapped at itself in red confusion. Renius growled a command and the others stepped back to allow him the kill.

As he landed the fatal blow, the other two lions attacked. One caught the head of the wounded man who had wandered away. A quick crack of the jaws and it was over. That lion settled down with the corpse, ignoring the other slaves as it bit into the soft abdomen and began to feed. It was quickly killed, speared on three blades in the mouth and chest.

Renius met the charge of the last to his left. His protecting slave was tumbled by the strike and over him came the snapping rage that was the male cat. Its paws were striking and great dark claws stood out like spear points, straining to pierce and tear. Renius balanced himself and struck into the chest. A wound opened with a rush of sticky dark blood, but the blade skittered off the breastbone and Renius was struck by a shoulder, only luck letting the jaws snap where he had been. He rolled and came up well, still with sword in hand. As the beast checked and turned back on him, he was ready and sent his blade into the armpit and the bursting heart. The strength went out of it in the instant, as if the steel had lanced a boil. It lay and bled into the sand, still aware and panting, but become pitiful. A soft moan came from deep within the bloody chest as Renius approached, drawing a dagger from his belt. Reddish saliva dribbled onto the sand as the torn lungs strained to fill with air.

Renius spoke softly to the beast, but the words could not be heard in the stands. He lay a hand on the mane and patted it absently, as he would a favourite hound. Then he slipped the blade into the throat and it was over.

The crowd seemed to draw breath for the first time in hours and then laughed at the release of tension. Four men were dead on the sand, but Renius, the old killer, still stood, looking exhausted. They began to chant his name, but he bowed quickly and left the ring, striding to the shadowed door and into darkness.

‘Get in quickly, Tubruk. You know my highest price. A year, mind – a full year of service.’

Tubruk disappeared into the crowds and the boys were left to make polite conversation with Julius. However, without Tubruk to act as a catalyst, the conversation died quickly. Julius loved his son, but had never enjoyed talking to the young. They prattled and knew nothing of decorum and self-restraint.

‘He will be a hard teacher, if his reputation is accurate. He was once without equal in the empire, but Tubruk tells the stories better than I.’

The boys nodded eagerly and determined to press Tubruk for the details as soon as they had the opportunity.

The seasons had turned towards autumn on the estate before the boys saw Renius again, dismounting from a gelding in the stone yard of the stables. It was a mark of his status that he could ride like an officer or a member of the Senate. Both of them were in the hay barn adjoining, and had been jumping off the high bales onto the loose straw. Covered in hay and dust, they were not fit to be seen and peered out at the visitor from a corner. He glanced around as Tubruk came to meet him, taking the reins.

‘You will be received as soon as you are refreshed from your journey.’

‘I have ridden less than five miles. I am neither dirty nor sweating like an animal. Take me in now, or I’ll find the way myself,’ snapped the old soldier, frowning.

‘I see you have lost none of your charm and lightness of manner since you worked with me.’

Renius didn’t smile and for a second the boys expected a blow, or a violent retort.

‘I see you have not yet learned manners to your elders. I expect better.’

‘Everyone is younger than you. Yes, I can see how you would be set in your ways.’

Renius seemed to freeze for a second, slowly blinking. ‘Do you wish me to draw my sword?’

Tubruk was still, and Marcus and Gaius noticed for the first time that he too wore his old gladius in a scabbard.

‘I wish you only to remember that I am in charge of the running of the estate and that I am a free man, like yourself. Our agreement benefits us both; there are no favours being done here.’

Renius smiled then. ‘You are correct. Lead on then to the master of the house. I would like to meet the man who has such interesting types working for him.’

As they left, Gaius and Marcus looked at each other, eyes aglow with excitement.

‘He will be a hard taskmaster, but will quickly become impressed at the talent he has on his hands …’ Marcus whispered.

‘He will realise that we will be his last great work, before he drops dead,’ Gaius continued, caught up in the idea.

‘I will be the greatest swordsman in the land, aided by the fact that I have stretched my arms every night since I was a baby,’ Marcus went on.

‘The fighting monkey, they will call you!’ Gaius declared in awe.

Marcus threw hay at his face and they grabbed each other with mock ferocity, rolling around for a second until Gaius ended up on top, sitting heavily on his friend’s chest.

‘I will be the slightly better swordsman, too modest to embarrass you in front of the ladies.’

He struck a proud pose and Marcus shoved him off into the straw again. They sat panting and lost in dreams for a moment.

At length, Marcus spoke: ‘In truth, you will run this estate, like your father. I have nothing and you know my mother is a whore … no, don’t say anything. We both heard your father say it. I have no inheritance save my name and that is stained. I can only see a bright future in the army, where at least my birth is noble enough to allow me high position. Having Renius as my trainer will help us both, but me most of all.’

‘You will always be my friend, you know. Nothing can come between us.’ Gaius spoke clearly, looking him in the eye.

‘We will find our paths together.’

They both nodded and gripped hands for a second in the pact. As they let go, Tubruk’s familiar bulk appeared as he stuck his head into the hayloft.

‘Get yourselves cleaned up. Once Renius has finished with your father, he’ll want some sort of inspection.’

They stood slowly, nervousness obvious in their movements.

‘Is he cruel?’ Gaius asked.

Tubruk didn’t smile.

‘Yes, he is cruel. He is the hardest man I have ever known. He wins battles because the other men feel pain and are frightened of death and dismemberment. He is more like a sword than a man and he will make you both as hard as himself. You will probably never thank him – you will hate him, but what he gives you will save your lives more than once.’

Gaius looked at him questioningly. ‘Did you know him before?’

Tubruk laughed, a short bark with no humour. ‘I should say so. He trained me for the ring, when I was a slave.’

His eyes flashed in the sun as he turned and he was gone.

Renius stood with his feet shoulder-width apart and his hands clasped behind his back. He frowned at the seated Julius.

‘No. If anyone interferes, I will leave on that hour. You want your son and the whore’s whelp to be made into soldiers. I know how to do that. I have been doing it, one way or another, all my life. Sometimes they only learn as the enemy charges, sometimes they never learn, and I have left a few of those in shallow foreign graves.’

‘Tubruk will want to discuss their progress with you. His judgement is usually first-rate. He was, after all, trained by you,’ Julius said, still trying to regain the initiative he felt he had lost.

This man was an overwhelming force. From the moment he entered the room, he had dominated the conversation. Instead of setting out the manner of his son’s teaching, as he had intended, Julius found himself on the defensive, answering questions about his estate and training facilities. He knew better now what he did not have than what he did.

‘They are very young, and …’

‘Any older would be too late. Oh, you can take a man of twenty and make him a competent soldier, fit and hard. A child, though, can be fashioned into a thing of metal, unbreakable. Some would say you have already left it too late, that proper training should commence at five years. I am of the opinion that ten is the optimum to ensure the proper development of muscle and lung capacity. Earlier can break their spirits; later and their spirits are too firmly in the wrong courses.’

‘I agree, to some ext—’

‘Are you the real father of the whore’s boy?’ Renius spoke curtly, but quietly, as if inquiring after the weather.

‘What? Gods, no! I –’

‘Good. That would have been a complication. I accept the year contract then. My word is given. Get the boys out into the stable yard for inspection in five minutes. They saw me arrive so they should be ready. I will report to you quarterly in this room. If you cannot make the appointment, be so good as to let me know. Good day.’

He turned on his heel and strode out. Behind him, Julius blew air out of puffed cheeks in a mixture of amazement and contentment.

‘Could be just what I wanted,’ he said, and smiled for the first time that morning.