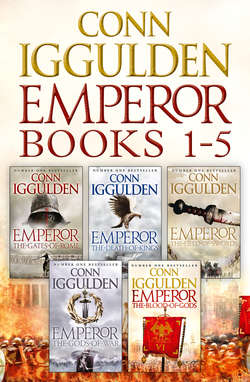

Читать книгу The Emperor Series Books 1-5 - Conn Iggulden - Страница 19

CHAPTER TEN

ОглавлениеThe fields were deserted by the time the sun came over the horizon. Those who had broken into the wine store were no doubt lying amongst the corn, still in the deep slumber of drunkenness. Gaius looked out over the wall to see sluggish smoke rising from the blackened ground. Scorched trees stood stark and bare, and the winter grain still smouldered in the skeletal wrecks of the feed barns.

It was a strangely peaceful scene, with even the morning birds silent. The violence and emotions of the night before were somehow distant when you were able to look out across the fields. Gaius rubbed his face for a moment, then turned to walk down the steps into the courtyard.

Brown stains spattered every white wall and surface. Pools of blood congealed in corners and obscene smears showed where the bodies had already been shifted, dragged outside the gates to be taken to pits when carts could be arranged. The defenders were laid out on clean cloths in cool rooms, their limbs arranged for dignity. The others were simply thrown onto a growing pile where arms and legs stuck out at angles. Gaius watched the work, and in the background heard the screams of the wounded as they were stitched or made ready for amputation.

He burned with anger and had nowhere to unleash it. He had been locked away for safety while everyone he loved risked their lives and while his father had given his in defence of his family and the estate. True, he had still been weak from the operation, his scabs barely healed, but to be denied the chance to help his father! There were no words, and when Cabera had come to him to offer sympathy Gaius ignored him until he went away. He sat exhausted and trickled dust through his fingers, remembering Tubruk’s words years before and understanding them at last. His land.

A slave approached, one whose name Gaius did not know, but who bore wounds that showed he had been part of the defence.

‘The dead are all outside the gates, master. Shall we find carts for them?’

It was the first time any man had addressed him as anything but his own name. Gaius hardened his expression so as not to reveal his surprise. His mind was full of pain and his voice sounded as if from a deep pit.

‘Bring lamp oil. I’ll burn them where they lie.’

The slave ducked his head in acknowledgement and ran for the oil. Gaius walked outside the gates and looked on the ungainly mass of death. It was a grisly sight, but he could find no sympathy in him. Each one there had chosen this end when they had attacked the estate.

He doused the pile in oil, sloshing it over the flesh and faces, into open mouths and unblinking eyes. Then he lit it and found he couldn’t watch the corpses burn after all. The smoke brought back a memory of the raven he and Marcus had caught and he called a slave over to him.

‘Fetch barrels from the stores and keep it burning until they are ash,’ he said grimly. He went back inside as the heat built and the smell followed him like an accusing finger.

He found Tubruk lying on his side and biting onto a piece of leather as Cabera probed a dagger wound in his stomach in the great kitchen. Gaius watched for a while, but no words were exchanged. He moved on, finding the cook sitting on a step with a bloody cleaver still in his hand. Gaius knew his father would have had words of encouragement for the man, who looked desolate and lost. He himself could not summon up anything except cold anger and stepped over the figure, who stared off into space as if Gaius wasn’t there. Then he stopped. If his father would have done it, then so would he.

‘I saw you fight on the wall,’ he said to the cook, his voice strong and firm at last.

The man nodded and seemed to gather himself. He struggled to stand.

‘I did, master. I killed a great number, but I lost count after a while.’

‘Well, I’ve just burned one hundred and forty-nine bodies, so it must have been many,’ Gaius said, trying to smile.

‘Yes. No one got past me. I have never known such luck. I was touched by the gods, I think. We all were.’

‘Did you see my father die?’

The cook stood and raised an arm as if to put it on the boy’s shoulder. At the last moment, he thought better of it and turned the gesture into a wave of regret.

‘I did. He took a great many with him and many before. There were piles around him at the end. He was a brave man and a good one.’

Gaius felt his calm waver at the kind thought and his jaw clenched. When he had overcome his surge of sorrow, he spoke graciously: ‘He would be proud of you, I know. You were singing when I caught a glimpse of you.’

To his surprise, the man blushed deeply.

‘Yes. I enjoyed the fight. I know there was blood and death all around, but everything was simple, you see. Anyone I could see was to be killed. I like things to be clear.’

‘I understand,’ Gaius said, forcing a bleak smile. ‘Rest now. The kitchens are open and soup will be brought around soon.’

‘The kitchens! And I am here! I must go, master, or the soup will be fit for nothing.’

Gaius nodded and the man bolted off, leaving his enormous cleaver resting against the step, forgotten. Gaius sighed. He wished his own life was that simple, to be able to take on and cast off roles without regret.

Lost in thought as he was, he didn’t notice the man’s return until he spoke.

‘Your father would be proud of you too, I think. Tubruk says you saved him when he was exhausted at the end, and with you injured as well. I would be proud if my son were as strong.’

Tears came unbidden to Gaius’ eyes and he turned away so the other would not see them. This was not the time to be breaking apart, not when the estate was in a shambles and the winter feed all burned. He tried to busy himself with the details, but he felt helpless and alone and the tears came more strongly, as his mind touched again and again on his loss, like a bird pecking at weeping sores.

‘Ho there!’ came a voice from outside the main gate.

Gaius heard the cheerful tone and composed himself. He was the head of the estate, a son of Rome and his father, and he would not embarrass the old man’s memory. He walked the steps to the top of the wall, barely aware of the phantom images that came rushing at him. Those were all from the dark. In the sun the shadows had little reality.

At the top, he looked down on the bronze helmet of a slim officer on a fine gelding that pawed the ground restlessly as it waited. The officer was accompanied by a contubernium of ten legionaries. Each man appeared alert and smartly turned out. The officer looked up and nodded to Gaius. He was around forty, tanned and fit-looking.

‘We saw your smoke. Came to investigate in case it was more of the slaves on the rampage. I see you’ve had trouble here. My name is Titus Priscus. I am a centurion with Sulla’s legion, who have just blessed the city with their presence. My men are ranging the countryside hereabouts, on clean-up and execution detail. May I speak to the master of the estate?’

‘That would be me,’ Gaius said. ‘Open the gates,’ he called below.

Those words achieved what all the marauders of the night before could not and the heavy gates were pulled open, allowing the men entry.

‘Looks like you had it rough out here,’ Titus said, all trace of cheerfulness gone from his voice and manner. ‘I should have known from the pile of bodies, but … did you lose many of your own?’

‘Some. We held the walls. How is the city?’ Gaius was at a loss as to what to say to the man. Was he meant to make polite conversation?

Titus dismounted and gave the reins to one of his men.

‘Still there, sir, although hundreds of wooden houses went up and there are a few thousand dead in the streets. Order has been restored for the moment, though I can’t say it would be safe to stroll out after dark. At the moment, we’re rounding up all the slaves we can find and crucifying one in ten to make an example – Sulla’s orders – on all the estates near Rome.’

‘Make it one in three if they’re on my land. I’ll replace them when things have settled. I don’t like the thought of letting anyone who fought against me last night go without punishment.’

The centurion looked at him for a second, unsure.

‘Begging your pardon, sir, but are you able to give that order? You’ll excuse me checking, but, in the circumstances, is there anyone to back you?’

For a second, anger flared in Gaius, but then he remembered what he must look like to the man. There had been no opportunity to clean himself up after Lucius and Cabera had restitched and rebandaged his wounds. He was dirty and bloodstained and unnaturally pale. He didn’t know that his blue eyes were also rimmed with red from the oily smoke and crying and that only something in his manner kept a seasoned soldier like Titus from cuffing the boy for his insolence. There was something, though, and Titus couldn’t have said exactly what it was. Just a feeling that this young man was not someone to cross lightly.

‘I would do the same in your position. I will fetch my estate manager, if the doctor is finished with him.’ Gaius turned away without another word.

It would have been politeness to offer the men refreshment, but Gaius was annoyed that he had to summon Tubruk to establish his bona fides. He left them waiting.

Tubruk was at least clean and dressed in good, dark clothing. His wounds and bandages were all concealed under his woollen tunic and bracae – leather trousers. He smiled as he saw the legionaries. The world was turning the right way up again.

‘Are you the only ones in this area?’ he asked without preamble or explanation.

‘Er, no, but …’ Titus began.

‘Good.’ Tubruk turned to Gaius. ‘Sir, I suggest you have these men send out a message that they will be delayed. We need men to get the estate back in order.’

Gaius kept his face as straight as Tubruk’s, ignoring Titus’ expression.

‘Good point, Tubruk. Sulla has sent them to help the outlying estates, after all. There is much work to be done.’

Titus tried again. ‘Here, now look …’

Tubruk noticed him once more. ‘I suggest you take the message yourself. These others look fit enough for a little hard labour. Sulla won’t want you to abandon us to our wreckage, I’m sure.’

The two men faced each other and Titus sighed, reaching up to remove his helmet.

‘Never let it be said that I shirked a job of work,’ he muttered. Turning to one of the legionaries, he jerked his head back to the fields. ‘Get back out and join up with the other units. Spread the word that I’ll be held up here for a few hours. Any slaves you find – tell them one in three, all right?’

The man nodded cheerfully and took off.

Titus began to unbuckle his breastplate. ‘Right, where do you want my lads to start?’

‘You handle this, Tubruk. I’ll go and check on the others.’ Gaius turned away, showing his appreciation with a quick grip of the other’s shoulder as he left. What he wanted to do was to go for a long walk in the woods by himself, or sit by the river pool and settle his thoughts. That would come later, though, after he had seen and spoken with every man and woman who had fought for his family the night before. His father would have done the same.

As he passed the stables, he heard a pulsing sob from the darkness within. He paused, unsure whether he should intrude. There was so much grief in the air, as well as inside him. Those who had fallen had friends and relatives who had not expected to begin this day alone. He stood for a moment longer, still smelling the oily stink of the bodies he had fired. Then he went into the cool shadow of the stalls. Whoever it was, their grief was now his responsibility, their burdens were his to share. That was what his father had understood and why the estate had prospered for so long.

His eyes adjusted slowly after the morning glare and he peered into each stall to find the source of the sounds. Only two held horses and they snickered gently to him as he reached and stroked their soft muzzles. His foot scraped against a pebble and the sobbing ceased on the instant, as if someone was holding their breath. Gaius waited, as still as Renius had taught him to stand, until he heard the sigh of released air and knew where the person was.

In the dirty straw, Alexandria sat with her knees tight against her chin and her back to the far stone wall. She looked up as he came into sight and he saw that the dirt on her face was streaked with tears. She was close to his own age, maybe a year older, he recalled. The memory of her being flogged by Renius came into his mind with a stab of guilt.

He sighed. He had no words for her. He crossed the short distance and sat against the wall next to her, taking care to leave space between them as he leaned back so that she would not be threatened. The silence was calm and the smells and feel of the stables had always been a comforting place to Gaius. When he was very young, he too had escaped here to hide from his troubles or from punishment to come. He sat, lost in memory for a while, and it didn’t seem awkward between them, though nothing was said. The only sounds were the horses’ movements and the occasional sob that still escaped Alexandria.

‘Your father was a good man,’ she whispered at last.

He wondered how many times he would hear the phrase before the day was over and whether he could stand it. He nodded mutely.

‘I’m so sorry,’ he said to her, feeling rather than seeing her head come up to look at him. He knew she’d killed, had seen her covered in blood down in the yard as he’d come out the night before. He thought he understood why she was crying and had meant to try and comfort her, but the words unlocked a rush of sorrow in him and his eyes filled with tears. His face twisted in pain as he bowed his head to his chest.

Alexandria looked at him in astonishment, her eyes wide. Before she had time to think, she had reached over to him and they were holding each other in the darkness, a blot of private grief while the world went on in the sun outside. She stroked his hair with one hand and whispered comfort to him as he apologised over and over, to her, his father, to the dead, to those he had burned.

When he was spent, she began to release him, but in the last fragment of time before he was too far she pressed her lips lightly on his, feeling him start slightly. She pulled away, hugging her knees tightly and, unseen in the shadows, her face burned. She felt his eyes on her, but couldn’t meet them.

‘Why did you …?’ he muttered, his voice hoarse and swollen from crying.

‘I don’t know. I just wondered what it would be like.’

‘What was it like?’ he replied, his voice strengthening with amusement.

‘Terrible. Someone will have to teach you to kiss.’

He looked at her, bemused. Moments before, he had been drowning in a sorrow that would not diminish or wane in him. Now he was noticing that beneath the dirt and wisps of straw and smell of blood – beneath her own sadness – there was a rare girl.

‘I have the rest of the day to learn,’ he said quietly, the words stumbling out past nervous blockages in his throat.

She shook her head. ‘I have work to do. I should be back in the kitchen.’

In a smooth movement, she rose from her crouch and left the stall, as if she was going to walk right away without another word. Then she paused and looked at him.

‘Thank you for coming to find me,’ she said and walked out into the sunlight.

Gaius watched her go. He wondered if she had realised he had never kissed a girl before. He could still feel a light pressure on his lips as if she had marked him. Surely she hadn’t meant terrible? He saw again the stiff way she had carried herself as she left the stables. She was like a bird with a broken wing, but she would heal with time and space and friends. He realised he would as well.

Marcus and Tubruk were laughing at something Cabera had said, as Gaius came into the room. At the sight of him, they all fell silent.

‘I came … to thank you. For doing what you did on the walls,’ Gaius began.

Marcus cut him off, stepping closer and grabbing his hand. ‘You never need to thank me for anything. I owe more than I could ever pay to your father. I was sorry to hear he fell at the last.’

‘We came through. My mother lives, I live. He would do it again if offered the chance, I know. You took some wounds?’

‘Towards the end. Nothing serious, though. I was untouchable. Cabera says I will be a great fighter.’ Marcus broke into a grin.

‘Unless he gets himself killed, of course. That would slow him down a little,’ Cabera muttered, busying himself with applying wax to the wood of his bow.

‘How is Renius?’ Gaius asked.

Both seemed to pause for a second at the question. Marcus looked evasive. There was something odd there, Gaius thought.

‘He’ll live, but it will be a long time before he’s ever fit again,’ Marcus said. ‘At his age an infection would be the end of him, but Cabera says he’ll make it.’

‘He will,’ Cabera said firmly.

Gaius sighed and sat down. ‘What happens now? I’m too young to take my father’s place, to represent his interests in Rome. In truth, I would not be happy running only the estate, but I never had time to learn about the rest of his affairs. I don’t know who looked after his wealth, or where the deeds to the land are.’ He turned to Tubruk. ‘I know you are familiar with some of it and I would trust you to control the capital until I am older, but what do I do now? Continue to hire tutors for Marcus and myself? Life seems suddenly vague; without direction, for the first time.’

Cabera stopped polishing at this outburst.

‘Everyone feels this at some time. Did you think I planned to be here when I was a young boy? Life has a way of taking twists and turns you did not expect. I would not have it any other way, for all the pain it brings. Too much of the future is already set, it is good that we cannot know every detail or life would become a grey, dull sort of death.’

‘You will have to learn fast, that is all,’ Marcus continued, his face alight with enthusiasm.

‘With Rome as it is? Who will teach me? This is not a time of peace and plenty, where my lack of political skill can be overlooked. My father was always very clear about that. He said Rome was full of wolves.’

Tubruk nodded grimly. ‘I will do what I can, but already some will be looking at which estates have been weakened and might be bought cheaply. This is not the time to be defenceless.’

‘But I don’t know enough to protect us!’ Gaius went on. ‘The Senate could take everything I own if I don’t pay taxes, for example, but how do I pay? Where is the money and where do I take it and how much should I pay? Where are the names of my father’s clients? You see?’

‘Be calm,’ Cabera said, beginning the slow strokes along the wood of his bow again. ‘Think instead. Let us begin with what you do have and not what you don’t know.’

Gaius took a deep breath and once again wished his father were there to be the rock of certainty in his life.

‘I have you, Tubruk. You know the estate, but not the other dealings. None of us know anything about politics or the realities of the Senate.’

He looked again at Cabera and Marcus. ‘I have you two and I have Renius on hand, but none of us have even entered the Senate chambers and my father’s allies are strangers to us.’

‘Concentrate on what we have, otherwise you will despair. So far you have named some very capable people. Armies have been started with less. What else?’

‘My mother and her brother Marius, but my father always said he was the biggest wolf of them all.’

‘We need a big wolf right now, though. Someone who knows the politics. He is your blood, you must go and see him,’ Marcus said quietly.

‘I don’t know if I can trust him,’ Gaius said, his expression bleak.

‘He will not desert your mother. He must help you to keep control of the estate, if only for her,’ Tubruk declared.

Gaius agreed slowly.

‘True. He has a place in Rome I could visit. There is no one else to help, so it must be him. He is a stranger to me, though. Since my mother began her sickness, he has rarely been to the estate.’

‘That will not matter. He will not turn you away,’ Cabera said peacefully, eyeing the shine he had wrought in the bow.

Marcus looked sharply at the old man. ‘You seem very sure,’ he said.

Cabera shrugged. ‘Nothing is sure in this world.’

‘Then it is settled. I will send a messenger before me and visit my uncle,’ Gaius said, something of his gloom lifting.

‘I will come with you,’ Marcus said quickly. ‘You are still recovering from your wounds and Rome is not a safe place at the moment, you know.’

Gaius smiled properly for the first time that day.

Cabera muttered, as if to himself, ‘I came to this land to see Rome, you know. I have lived in high mountain villages and met tribes thought lost to antiquity on my travels. I believed I had seen everything, but all the time people told me I had to visit Rome before I died. I said to them, “This lake is true beauty”, and they would reply, “You should see Rome.” They say it is a wondrous place, the centre of the world, yet I have never stepped inside its walls.’

Both boys smiled at the old man’s transparent subterfuge.

‘Of course you will come. I consider you a friend of the house. You will always be welcome anywhere I am, on my honour,’ Gaius replied, his tone formal, as if repeating an oath.

Cabera laid the bow aside and stood with his hand outstretched. Gaius took it firmly.

‘You too will always be welcome at my home fires,’ Cabera said. ‘I like the climate around here, and the people. I think my travels will wait for a little while.’

Gaius released the grip, his expression thoughtful.

‘I will need good friends around me if I am to survive my first year of politics. My father described it as walking barefoot in a nest of vipers.’

‘He seems to have had a colourful turn of phrase, and not a high opinion of his colleagues,’ Cabera said, giving out a dry chuckle. ‘We will tread lightly and stamp on the occasional head as it becomes necessary.’

All four smiled and felt the strength that comes from such a friendship, despite the difference in age and background.

‘I would like to take Alexandria with us,’ Gaius added suddenly.

‘Oh, yes? The pretty one?’ Marcus replied, his face lighting up.

Gaius felt his cheeks grow red and hoped it wasn’t obvious. Judging by the expressions of the others, it was.

‘You will have to introduce me to this girl,’ Cabera said.

‘Renius whipped her, you know, for distracting us at practice,’ Marcus continued.

Cabera tutted to himself. ‘He can be charmless. Beautiful women are a joy in life …’

‘Look, I …’ Gaius began.

‘Yes, I’m sure you want her simply to hold the horses or something. You Romans have such a way with women, it is a wonder your race has survived.’

Gaius left the room after a while, leaving laughter behind him.

Gaius knocked at the door of the room where Renius lay. He was alone for the moment, although Lucius was nearby and had just been in to check the wounds and stitches. It was dark in the room and at first Gaius thought the old man was asleep.

He turned to leave rather than disturb the rest he must need, but a whispering voice stopped him.

‘Gaius? I thought it was you.’

‘Renius. I wanted to thank you.’ Gaius approached the bed and drew up a chair beside the figure. The eyes were open and clear and Gaius blinked as he took in the features. It must have been the dim light, but Renius looked younger. Surely not, yet there was no denying that some of the deep-seam wrinkles had lessened and a few black hairs could be seen at the temples, almost invisible in the light, but standing out against the white bristles.

‘You look … well,’ Gaius managed.

Renius gave a short, hard chuckle. ‘Cabera healed me and it has worked wonders. He was more surprised than anyone, said I must have a destiny or something, to be so affected by him. In truth, I feel strong, although my left arm is still useless. Lucius wanted to take it off, rather than have it flapping around. I … may let him, when the rest of me has healed.’

Gaius absorbed this in silence, fighting back painful memories.

‘So much has happened in such a short time,’ he said. ‘I am glad you are still here.’

‘I couldn’t save your father. I was too far away and finished myself. Cabera said he died instantly, with a blade in his heart. Most likely, he wouldn’t even have known it.’

‘It’s all right. You don’t need to tell me. I know he would have wanted to be on that wall. I would have wanted it too, but I was left in my room, and …’

‘You got out though, didn’t you? I’m glad you did, as it turned out. Tubruk says you saved him right at the end, like a … reserve force.’ The old man smiled and coughed for a while. Gaius waited patiently until the fit was over.

‘It was my order to leave you out of it. You were too weak for hours of fighting and your father agreed with me. He wanted you safe. Still, I’m glad you got out for the end of it.’

‘So am I. I fought with Renius!’ Gaius said, his eyes brimming with tears, though he smiled.

‘I always fight with Renius,’ muttered the old man. ‘It isn’t that much to sing about.’