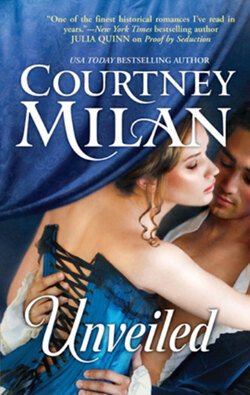

Читать книгу Unveiled - Courtney Milan - Страница 10

CHAPTER ONE

ОглавлениеSomerset, August 1837

SO THIS WAS HOW IT felt to be a conquering hero.

Ash Turner—once plain Mr. Turner; now, so long as fate stayed Parliament’s hand, the future Duke of Parford—sat back on his horse as he reached the crest of the hill.

The estate he would inherit was laid out in the valley before him. Stone walls and green hedges hugged the curves of the limestone hill where his horse stood, breaking the brilliant apple-green growth of high summer into gentle, rolling squares of patchwork. A small cottage stood to the side of the road. He could hear the hushed whispers of the farm children, who had crept out to gawk at him as he passed.

Over the past few months, he’d become accustomed to being gawked at.

Behind him, his younger brother’s steed stamped and came to a halt. From this high vantage point, they could see Parford Manor—an impressive four-story, five-winged affair, its brilliant windows glittering in the sunlight. Undoubtedly, someone had set a servant to watch for his arrival. In a few moments, the staff would spill out onto the front steps, arranging themselves in careful lines, ready to greet the man who would be their master.

The man who’d stolen a dukedom.

A smile played over Ash’s face. Once he inherited, nobody would gainsay him.

“You don’t have to do this.” The words came from behind him.

Nobody, that was, except his little brother.

Ash turned in the saddle. Mark was facing forwards, looking at the manor below with an abstracted expression. That detached focus made him look simultaneously old, as if he deserved an elder’s beard to go with that inexplicable wisdom, and yet still unaccountably boyish.

“It’s not right.” Mark’s voice was barely audible above the wind that whipped at Ash’s collar.

Mark was seven years younger than Ash, which made him by most estimations firmly an adult. But despite all that Mark had experienced, he had somehow managed to retain an aura of almost painful purity. He was the opposite of Ash—blond, where Ash’s hair was dark; slim, where Ash’s shoulders had broadened with years of labor. But most of all, Mark seemed profoundly, sacredly innocent, where Ash felt tired and profane. Perhaps that was why the last thing Ash wanted to do in his moment of victory was to hash through the ethics.

Ash shook his head. “You asked me to find you a quiet country home for these last weeks of summer, so you might work in peace.” He spread his arms, palms up. “Well. Here you are.”

Down in the valley, the first ranks of servants had begun to gather, jockeying for position on the wide steps leading up to the massive front doors.

Mark shrugged, as if this evidence of prosperity meant nothing to him. “A house back in Shepton Mallet would have done.”

A tight knot formed in Ash’s stomach. “You’re not going back to Shepton Mallet. You’re never going back there. Do you suppose I would simply kick you from a carriage at Market Cross and let you disappear for the summer?”

Mark finally broke his gaze from the tableau in front of them and met Ash’s eyes. “Even by your extravagant standards, Ash, you must admit this is a bit much.”

“You don’t think I would make a good duke? Or you don’t approve of the method I used to inveigle a summer’s invitation to the ducal manor?”

Mark simply shook his head. “I don’t need this. We don’t need this.”

And therein lay Ash’s problem. He wanted to make up for every last bit of his brothers’ childhood deprivation. He wanted to repay every skipped meal with twelve-course dinners, gift a thousand pairs of gloves in exchange for every shoeless winter. He’d risked his life building a fortune to ensure their happiness. Yet both his brothers declared themselves satisfied with a few prosaic simplicities.

Simplicities wouldn’t make up for Ash’s failure. So maybe he had overindulged when Mark finally asked him for a favor.

“Shepton Mallet would have been quiet,” Mark said, almost wistfully.

“Shepton Mallet is halfway to dead.” Ash clucked to his horse. As he did so, the wind stopped. What he’d intended as a faint sound of encouragement sounded overloud. The horse started down the road towards the manor.

Mark kicked his mare into a trot and followed.

“You’ve never thought it through,” Ash tossed over his shoulder. “With Richard and Edmund Dalrymple no longer able to inherit, you’re fourth in line for the dukedom. There are a great many advantages to that. Opportunities will arise.”

“Is that how you’re describing your actions, this past year? ‘No longer able to inherit?’”

Ash ignored this sally. “You’re young. You’re handsome. I’m sure there are some lovely milkmaids in Somerset who would be delighted to make the acquaintance of a man who stands an arm’s length from a dukedom.”

Mark stopped his horse a few yards before the gate to the grounds. Ash felt a fillip of annoyance at the delay, but he halted, too.

“Say it,” Mark said. “Say what you did to the Dalrymples. You’ve spouted one euphemism after another ever since this started. If you can’t even bring yourself to speak the words, you should never have done it.”

“Christ. You’re acting as if I killed them.”

But Mark was looking at him, his blue eyes intense. In this mood, with the sun glancing off all that blond hair, Ash wouldn’t have been surprised if his brother had pulled a flaming sword from his saddlebag and proclaimed him barred from Eden forever. “Say it,” Mark repeated.

And besides, his little brother so rarely asked anything of him. Ash would have given Mark whatever he wanted, so long as he just…well, wanted.

“Very well.” He met his brother’s eyes. “I brought the evidence of the Duke of Parford’s first marriage before the ecclesiastical courts, and thus had his second marriage declared void for bigamy. The children resulting from that union were declared illegitimate and unable to inherit. Which left the duke’s long-hated fifth cousin, twice removed, as the presumptive heir. That would be me.” Ash started his horse again. “I didn’t do anything to the Dalrymples. I just told the truth of what their own father had done all those years ago.”

And he wasn’t about to apologize for it, either.

Mark snorted and started his horse again. “And you didn’t have to do that.”

But he had. Ash didn’t believe in foretellings or spiritual claptrap, but from time to time, he had…premonitions, perhaps, although that word smacked of the occult. A better phrase might have been that he possessed a sheer animal instinct. As if the reactive beast buried deep inside him could recognize truths that human intelligence, dulled by years of education, could not.

When he’d found out about Parford, he’d known with a blazing certainty: If I become Parford, I can finally break my brothers free of the prison they’ve built for themselves.

With that burden weighing down one side of the scale, no moral considerations could balance the other to equipoise. The disinherited Dalrymples meant nothing. Besides, after what Richard and Edmund had done to his brothers? Really. He shed no tears for their loss.

The servants had finished gathering, and as Ash trotted up the drive, they held themselves at stiff attention. They were too well trained to gawk, too polite to let more than a little rigidity infect their manner. Likely, they were too accustomed to their wages to do more than grouse about the upstart heir the courts had forced upon them.

They’d like him soon enough. Everyone always did.

“Who knows?” he said quietly. “Maybe one of these serving girls will catch your eye. You can have any one you’d like.”

Mark favored him with an amused look. “Satan,” he said, shaking his head, “get thee behind me.”

Ash’s steed came to a stop and he dismounted slowly. The manor looked smaller than Ash remembered, the stone of its facade honey-gold, not bleak and imposing. It had shrunk from the unassailable fortress that had loomed in Ash’s head all these years. Now it was just a house. A big house, yes, but not the dark, menacing edifice he’d brooded over in his memory.

The servants stood in painful, ordered rows. Ash glanced over them.

There were probably more than a hundred retainers arrayed before him, all dressed in gray. He felt as sober as they appeared. Had there been the slightest danger of Mark accepting his cavalier offer, Ash would never have made it. These people were his dependents now—or they would be, once the current duke passed on. His duty. Their prosperity would hang on his whim, as his had once hung on Parford’s. It was a weighty responsibility.

I’m going to do better than that old bastard.

A vow, that, and one he meant every bit as much as the last promise he’d sworn, looking up at this building.

He turned to greet the majordomo, who stepped forwards. As he did so, he saw her. She stood on the last row of steps, a few inches apart from the rest of the servants. She held her head high. The wind started up again, as if the entire universe had been holding its breath up until this moment. She was looking directly at him, and Ash felt a cavernous hollow open deep in his chest.

He’d never seen the woman before in his life. He couldn’t have; he would have remembered the feel of her, the sheer rightness of it. She was pretty, even with that dark hair pulled into a severe knot and pinioned beneath a white lace cap. But it wasn’t her looks that caught his attention. Ash had seen enough beautiful women in his time. Maybe it was her eyes, narrowed and steely, fixed on him as if he were the source of all that was wrong in the world. Maybe it was the set of her chin, so unyielding, so fiercely determined, when every face around hers mirrored uncertainty. Whatever it was, something about her resonated deep within him.

It reminded him of the cacophony of an orchestra as it tuned its instruments: dissonance, suddenly resolving into harmony. It was the rumble, not of thunder, but its low, rolling precursor, trembling on the horizon. It was all of that. It was none of that. It was sheer animal instinct, and it reached up and grabbed him by the throat. Her. Her.

Ash had never ignored his instincts before—not once. He swallowed hard as the majordomo approached.

“One thing,” he whispered to his brother. “The woman in the last row—on the far right? She’s mine.”

Before his brother could do more than frown at him, before Ash himself could swallow the lingering feeling of sparks coursing through his veins, the majordomo was upon them, bowing and introducing himself. Ash took a deep breath and focused on the man.

“Mr.— I mean, my—” The man paused, uncertain how to address Ash. With the duke still alive, Ash, a mere distant cousin, held no title. And yet he had come here as heir to the dukedom, on the strictest orders from Chancery. Ash could guess at the careful calculation in the majordomo’s eyes: should he risk offending the man who might well be his next master? Or ought he adhere to the strict formalities required by etiquette?

Ash tossed his reins to the groom who crept forwards. “Plain Mr. Turner will do. There’s no need to worry about how you address me. I scarcely know what to call myself.”

The man nodded and the taut muscles in his face relaxed. “Mr. Turner, shall I arrange a tour, or would you and your brother care to take some refreshment first?”

Ash’s eyes wandered to the woman in the back row. She met his gaze, her expression implacable, and a queer shiver ran down his spine. It was not lust itself he felt, but the premonition of desire, as if the wind that whipped around his cravat were whispering in his ears. Her. Choose her.

“Good luck,” Mark muttered. “I don’t believe she likes you all that much.”

That much Ash had gleaned from the set of her jaw.

“No refreshment,” Ash said aloud. “No rest. I want to know everything, and the sooner, the better. I’ll need to speak with Parford, as well. I’d best start as I mean to go on.” He glanced at the woman one last time, and then met his brother’s eyes. “After all, I do enjoy a challenge.”

FROM HER HIGH PERCH on the cold stone steps, Anna Margaret Dalrymple could make out little in the features of the two gentlemen who approached on horseback. But what she could see did not bode well for her future.

Ash Turner was both taller and younger than she had expected. Margaret had imagined him arriving in a jewel-encrusted carriage, pulled by a team of eight horses—something both ridiculously feminine and outrageously ostentatious, to match his reputation as a wealthy nabob. The man who had taken everything from her should have been some hunched creature, prematurely bald, capable of no expression except an insolent sneer.

But this man sat his horse with all the ease and grace of an accomplished rider, and she could not make out a single massive, unsightly gem anywhere on his person.

Drat.

As Mr. Turner cantered up, the servants—it was difficult to think of them as fellow servants, when she was used to thinking of them as hers—tensed, breath held. And no wonder. This man had supplanted her brother, the rightful heir, through ruthless legal machinations. If Richard failed in his bid to have the Duke of Parford’s children legitimized by act of Parliament, Mr. Turner would be the new master. And when her father died, Margaret would find herself a homeless bastard.

He dismounted from his steed with ease and tossed the reins to the stable boy who dashed out to greet him. While he exchanged a few words with the majordomo, she could sense the unease about her, multiplying itself through the shuffling of feet and the uncertain rubbing of hands against sides. What sort of a man was he?

His gaze swept over them, harsh and severe. For one brief second, his eyes came to rest on Margaret. It was an illusion, of course—a wealthy merchant, come to investigate his patrimony, would care nothing for a servant clad in a shapeless gray frock, her hair secured under a severe mobcap. But it seemed as if he were looking directly inside her, as if he could see every day of these past painful months. It was as if he could see the empty echo of the lady she had been. Her heart thumped once, heavily.

She’d counted on being invisible to him in this guise.

Then, as if she’d been but a brief snag in the fluid silk of his life, he looked away, finishing his survey of the massed knot of servants. Beside her, the upstairs maids held their breath. Margaret wished he would just get it over with and say something dastardly, so they could all hate him.

But he smiled. It was an easy, casual expression, and it radiated a good cheer that left Margaret feeling perversely annoyed. He took off his black leather riding gloves and turned to address them.

“This place,” he said in a voice that was quiet yet carrying, “looks marvelous. I can tell that Parford Manor is in the hands of one of the finest staffs in all of England.”

Margaret could see the effect of those words travel like a wave through the servants. Backs straightened, subtly; eyes that had been narrowed relaxed. Hands unclenched. They all leaned towards him, just the barest inch, as if the sun had peeked out from behind disapproving clouds.

Just like that, he was stealing from her again. This time, he robbed her of the trust and support of her family retainers.

Mr. Turner, however, didn’t seem to realize his cruelty.

He removed his riding coat, revealing broad, straight shoulders—shoulders that ought to have bowed under the sheer villainous weight of what he’d done. He turned back to the majordomo. He acted as if he were not stealing onto Parford lands, as if he hadn’t won the grudging right to come here in Chancery a bare few weeks ago to investigate what he had called economic waste.

Smith, the traitor, was already beginning to relax in response.

Margaret had assumed that the servants were hers. After all those years running the house alongside her mother, she’d believed their loyalties could not be suborned.

But Mr. Smith nodded at something Mr. Turner said. Slowly, her servant—her old, faithful servant, whose family had served hers for six generations—turned and looked in Margaret’s direction. He held out his hand, and Mr. Turner looked up at her. This time, his gaze fixed on her and stayed. The wind blew, whipping her skirts about her ankles, as if he’d called up a gale with the intensity of his stare.

She couldn’t hear Smith’s commentary, but she could imagine his words delivered in his matter-of-fact tenor. “That’s Anna Margaret Dalrymple there, His Grace’s daughter. She’s stayed behind on Parford lands to report your comings and goings to her brothers. Oh, and she’s pretending to be the old duke’s nurse, because they’re afraid you’ll kill the man to influence the succession.”

Mr. Turner put his head to the side and blinked at her, as if not believing his eyes. He knew who she was; he had to know, or he’d not be looking at her like that. He wouldn’t be stalking towards her, his footfalls sure as a tiger’s. Now, she could see the windswept tousle of his hair, the strong line of his jaw. As he came closer, she could even make out the little creases around his mouth, where his smile had left lines.

It seemed entirely wrong that someone so awful could be so handsome.

Mr. Turner came to stand in front of her. Margaret tilted her chin up, so that she could look him in the eyes, and wished she were just a little taller.

He was studying her with something like bemusement. “Miss?” he finally asked.

Smith came up beside Margaret. “Ah, yes. Mr. Turner, this is Miss…” He paused and glanced at her, and in that instant, the growing bubble of betrayal was pricked, and she realized he had not given her secrets away. Ash Turner didn’t know who she was.

“Miss Lowell.” She remembered to curtsy, too, ducking her head as a servant would. “Miss Margaret Lowell.”

“You’re Parford’s nurse?”

Nurse; daughter. With his illness, it came to the same thing. She was the only protection her father had against this man, with her brothers scattered across England to fight for their inheritance in Parliament. She met Mr. Turner’s gaze steadily. “I am.”

“I should like to speak with him. Smith tells me you’re very strict about his schedule. When would it least inconvenience you?”

He gave her a great big dazzling smile that felt as if he’d just opened the firebox on a kitchen range. As bitterly as she disliked him, she still felt its effect. This was how this man, barely older than her, had managed to make a fortune so quickly. Even she wanted to jump to attention, to scurry just a little faster, just so he would favor her with that smile again.

Instead, she met his eyes implacably. “I’m not strict.” She drew herself up a little taller. “Strict implies unnecessary, but I assure you the care I take is very necessary indeed. His Grace is old. He is ill. He is weak, and I won’t brook any nonsense. I won’t have him disturbed just because some fool of a gentleman bids me do so.”

Mr. Turner’s smile grew as she spoke. “Precisely so,” he said. “Tell me, Miss…” he paused there and lowered one eyelid at her in a shiver of a languid wink. “Miss Margaret Lowell, do you always speak to your new employers in this manner, or is this an exception carved out for me in particular?”

“While Parford lives, you are not my employer. And when he has—” Her throat caught at the words; her lungs burned at the memory of the last grave she’d stood beside.

Hold yourself together, Margaret chided herself, or he’ll know who you are before the day’s over.

She cleared her throat and enunciated with particular care. “And once he’s passed on, you’ll hardly have need of my services. Not unless you’re planning on becoming bedridden yourself. Is there any chance of that?”

“Fierce and intelligent, too.” He let out a little sigh. “When I’m in bed, I don’t suppose I’ll want your services. Leastwise, not as a nurse. So yes, you are quite correct.”

His eyelashes were unconscionably thick. They shielded eyes so dark she could not distinguish pupil from cornea. It took her a moment to realize that what he’d said went well beyond idle flirtation. Smith coughed uneasily. He’d overheard the whole thing, from that unfortunate compliment to the improper innuendo. How horrifying. How lowering.

Still, the image came to mind unbidden—Mr. Turner, stripped of those layers of dark blue wool and pristine linen, his skin shining gold against white sheets, turned over on his side, that smile glinting just for her.

How enticing.

Margaret pressed her lips together and imagined herself emptying the chamber pot over his naked form. Now there was a thought that would bring her some satisfaction.

He leaned in. “Tell me, Miss Lowell. Is Parford well enough for a little conversation? You can accompany me to the room and make sure I don’t overstep myself or overexcite him.”

“He was alert earlier.” And, in point of fact, her father had insisted that when that devil Turner arrived, he wanted to see him straight away. “I’ll see if he’s still awake and willing to speak with you.”

She turned away, but he caught her wrist. She turned reluctantly back towards him. His naked hand was warm against her skin. She wished he hadn’t removed his gloves. His grip was not tight, but it was strong.

“One last question.” His eyes found hers. “Why did the majordomo hesitate before pronouncing your name?”

So he’d noticed that, too. In circumstances such as this, only the truth would do.

“Because,” she said with a sigh, “I’m a bastard. It’s not precisely clear what name I should be given.”

“What? No family? No one to stand for you and protect your good name? No brothers to beat off unwanted suitors?” His fingers tightened on her wrist a fraction; his gaze dipped downwards, briefly, to her bosom, before returning to her face. “Well. That’s a shame.” He smiled at her again, as if to say that there was no shame at all—at least not for him.

And that smile, that dratted smile. After all that he’d done to her, he thought he could waltz into her family home and take her to bed?

But he gave a sigh and let go of her hand. “It’s a terrible shame. I make it a point of honor not to impose upon defenseless women.”

He shook his head, almost sadly, and turned to gesture behind him. The young man who had accompanied him when he’d arrived loped up the steps in response.

“Ah, yes,” he said. “Miss Lowell, let me present to you my younger brother, Mr. Mark Turner. He’s come into the country with me this fine summer so he can have some quiet time to finish the philosophical tract he is writing.”

“It’s not precisely a philosophical tract.”

Mr. Mark Turner, unlike his brother, was slight—not skinny, but wiry, his muscles ropy. He was a few inches shorter than his elder brother, and in sharp contrast with his brother’s tanned complexion and dark hair, he was pale and blond.

“Mark, this is Miss Lowell, Parford’s nurse. Undoubtedly, she needs all her patience for that old misanthrope, so treat her kindly.” Mr. Turner grinned, as if he’d said something very droll.

Mr. Mark Turner did not appear to think it odd that his brother had introduced him to a servant—worse, that he had introduced a servant to him. He just looked at his brother and very slowly shook his head, as if to reprove him. “Ash” was all he said.

The elder Turner reached out and ruffled his younger brother’s hair. Mr. Mark Turner did not glower under that touch like a youth pretending to be an adult; neither did he preen like a child being recognized by his elder. He could not have been more than four-and-twenty, the same age as Margaret’s second-eldest brother. Yet he stood and regarded his brother, unflinching under his touch, his eyes steady and ageless.

It was as if they’d exchanged an entire conversation with those gestures. And Margaret despised Mr. Turner all the more for that obvious affection between him and his younger brother. He wasn’t supposed to be handsome. He wasn’t supposed to be human. He wasn’t supposed to have any good qualities at all.

One thing was for certain: Ash Turner was going to be a damned nuisance.