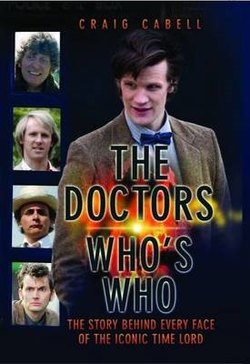

Читать книгу The Doctors Who's Who - The Story Behind Every Face of the Iconic Time Lord: Celebrating its 50th Year - Craig Cabell - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

DOCTOR WHO

Оглавление‘He wondered, then, if the others who had remained on Earth experienced the void this way.’

Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?

Philip K. Dick

WHO IS RESPONSIBLE for creating Doctor Who?

It’s not an easy question to answer. A TV show has many people who play a major role in creating it, from its initial idea through to its first transmission, but Sydney Newman must be recognised as the catalyst, the person who laid down the fundamental building blocks for Doctor Who and, most importantly, the main character.

Sydney Cecil Newman was born in Toronto, Canada, in 1917. He was educated at Ogden Public School and the Central Technical School, Toronto, where he studied painting, stagecraft, industrial and interior design. His skills were put to work as an artist, designing posters for cinemas and theatres in Toronto, but he soon branched out.

In 1938, Newman decided to go to Hollywood, where he was offered a job by the Walt Disney Company, who were impressed by the young man’s skills as a graphic designer. Unfortunately, he couldn’t obtain a work permit and had to return to Toronto where, in 1941, he secured employment with the National Film Board of Canada as an assistant film editor.

Later, Newman returned to America to study their film techniques. He would incorporate what he learned into the ever-growing Canadian broadcasting industry. In the 1950s, he moved across to Britain and became Head of Drama at ABC (former Thames Television), where he created SF shows like Pathfinders in Space and such cult TV series as The Avengers.

One of Newman’s strengths was his ability to gather the right team of individuals together to make a quality TV series. This was quintessential to his success and, ostensibly, the individual show’s success too.

In 1962, Newman moved from ABC to the BBC. Again Head of Drama, he was given the task of trying to fill the gap between Grandstand and Juke Box Jury on a Saturday afternoon. For the time slot, the show had to be for children. Traditionally, the spot had been filled with a classic serial, such as Oliver Twist or Kidnapped, but it was time for something else. Something different.

Donald Wilson was appointed Head of Serial and Series, and began to forge the initial ideas of what would become Doctor Who with Newman; but what would the show be about?

A report concerning the development of the show, written in July 1962, stated that ‘bug-eyed monsters’ were out but time travel was in. The idea continued to be developed and, in March 1963, a second report proposed a 52-week serial featuring ‘scientific troubleshooters’, with a time machine. The characters would include a handsome young man, an attractive young woman and a ‘mature man’ somewhere between 30 and 40 years of age, with some kind of twist to him.

Sydney Newman wasn’t totally happy with the report. He didn’t like the ‘scientific troubleshooters’ bit. He wanted the show to be different and, for a SF show, educational. He also wanted to include ‘a kid’ who would get into trouble, perhaps somebody the young audience could identify with.

Newman developed the idea further himself, writing a three-page document about ‘Dr Who’ (who is this man? Nobody knows – ‘Dr Who?’). ‘Dr Who’ was ‘a frail old man lost in space and time…’ but apart from that nothing else was known about him. From here, the show really started to take shape.

The script unit was now brought in. C E Webber (aka ‘Bunny Webber’ to his friends) was the first to try to make sense of this unusual show. It is unclear if Webber wrote a script or an extended treatment based upon Newman’s idea of the regular characters being shrunk to the size of a pinhead and exploring a school laboratory. What is clear is that the script/treatment was rejected and David Whitaker was brought in as story editor and Australian writer Anthony Coburn as scriptwriter. Coburn would eventually write the first useable script. But first Newman and Wilson decided to find a producer. It was Newman who suggested a young lady from his former employer, ABC Television, Verity Lambert. They interviewed her and almost immediately she was offered the job. She accepted.

Verity Lambert and the director of the first Doctor Who story, Waris Hussein, did the casting. Lambert cast a friend of hers, Jacqueline Hills as Barbara Wright, while William Russell was cast as Chesterton. The casting of Susan came about by accident, when Hussein glanced at a girl, Carole Ann Ford, while passing a set one day, and was struck by the way she presented herself on and off camera. Hussein instantly asked Lambert down to the set, who agreed with the director that Ford was exactly what they were looking for and soon offered her the part, which she duly accepted.

Ford remembers the chance meeting: ‘I was doing one of The Wednesday Plays, when Waris Hussein, the original director of Doctor Who, spotted me. He was up in the control box and I was on the set – screaming. I think they chose me because they wanted a good screamer. I certainly did an awful lot of it!’

Casting the Doctor was slightly more difficult. Both Lambert and Hussein had their own ideas, which included Cyril Cusack and Leslie French, but the actors weren’t interested. William Hartnell became the next choice. Hartnell was an actor worried about being typecast. He had played an army sergeant in the movie The Way Ahead and the TV series The Army Game. He also appeared as one again in the very first Carry On movie, Carry On Sergeant. It seemed that, if there was a soldier or hard-man role, he would be cast, but the role of the Doctor presented a new challenge. He was offered the part despite Lambert and Hussein’s concerns that a mature actor such as Hartnell wouldn’t want to take on a single role for 52 weeks. But their fears were short-lived, as Hartnell accepted the part and delighted in telling all his friends that he was to star in a children’s television series.

The main ingredients of what was to become the longest-running SF TV series ever had now been gathered together. Newman, Wilson, Lambert, Whitaker and Hussein were the main people who devised the show and then brought it to the screen.

It was essentially Newman who shaped the lead character of the Doctor on paper during the early reports, but David Whitaker was not a sleeping partner in this process. In fact, his original idea of introducing the Doctor at the end of a road in a swirling fog (titled ‘Nothing at the End of the Lane’), while not used on screen, was later used in book form, at the beginning of the first novel spawned from the show Doctor Who and the Daleks (Muller, 1964). Slightly different from the TV show, Whitaker wrote the first Doctor Who novelisation introducing the characters the way he had originally visualised them for screen, and then he amalgamated the show’s second broadcast story, about the Daleks, as the main story (which of course the first broadcast story wasn’t). So the writer had strong ideas that he could see through to their natural conclusion, albeit in a slightly different medium, and combined with Terry Nation’s Daleks – creatures that were not developed until the late summer of 1963 – he could create a one-off novel.

Newman certainly liked tried-and-trusted people around him. Verity Lambert was a known entity, as were David Whitaker and Anthony Coburn.

Coburn wrote the first episode, the first draft of which was completed by the end of April 1963. It was 43 pages long and entitled ‘Doctor Who and the Tribe of Gum’, subtitled ‘Episode One “An Unearthly Child”’.

The first draft of this script has only recently surfaced and is one of the most important documents in our understanding of how the show was developed. At the time of the first draft script, the characters were still far from formed. Although the script was essentially what later became the first ever episode, it had some very different dialogue to that which we see on screen. Firstly, the script did not mention the ‘Tardis’. The Doctor’s ship is indeed a police telephone box but no reference is made to its name, unlike in the first transmitted episode. Additionally, in order to pilot ‘the ship’, as it was referred to, the Doctor had to sit down at the control panel and strap himself in, so some traditional ‘rocket’ ideas hadn’t been ruled out by the time of the first draft script.

What is also interesting is that Barbara Wright’s character is called Miss Canning and the reason she wants to talk to fellow schoolteacher Ian Chesterton about the bright but strange ‘Suzanne Foreman’ is that she is new at the school and wants to confide in another teacher and not bother the headteacher. In the copy of the first draft script used in research for this book, the first time Miss Canning’s character is mentioned in the script her name is crossed out in pencil and the name Barbara Wright is inserted.

It was after this first draft that Miss Canning was developed into Barbara Wright, and ‘Suzanne’ became ‘Susan’. Also Newman wasn’t one hundred per cent happy with the script in other areas. There was an expensive element to it to begin with: when the two schoolteachers jump into ‘the ship’, it is still a police box, it was only when the door was shut that it transported them into the main control room. It was decided that this piece should be kept simple, losing a very eerie moment in which Suzanne’s favourite music is being played in the empty police box but the schoolteachers can’t see where it is coming from.

Another important part of the first draft script is where the Doctor refers to himself as ‘Doctor Who’. He says that in Earth language his name is translated to ‘Doctor Who’. This is important in regard to the six-page breakdown of the developed show, which was sent out to people by Whitaker when being offered to write or act in the show. It clearly stated on that document that the companions refer to the Doctor as ‘Doctor Who’, which is what happens in the first ever TV episode. Also Miss Canning is suddenly Barbara Wright in the six-page breakdown. This is very important because it is clear that Carole Ann Ford didn’t read the first draft script (where she is ‘Suzanne’ not ‘Susan’). That was only sent to writers before casting, and as an aide-memoire of how to write for the show. The version Ford got was the final version of the script with the names changed and plotlines and main character developed (in line with the six-page synopsis). This is a great shame, because, if she had read the first draft script, she could have found out what her relationship to the Doctor actually was (one of the show’s great mysteries).

The nuances of the first draft script of ‘An Unearthly Child’ have only recently been appreciated. Susan, or ‘Suzanne’, explained that her parents are dead and her world is gone and that all she has left is her grandfather and the ship. Little insight perhaps until the Doctor refuses to let the schoolteachers leave the ship. Suzanne tries to help them understand but they are worried about her welfare and argue with the Doctor, who they believe is deranged.

It is here that a very sinister piece starts, which was changed dramatically in the final draft of the script. To begin with, Suzanne states, ‘I’m trying to save you both’, implying that the Doctor wants to kill them. She goes on to say that ‘… if you both behave like… like primitives. If you insult him… He won’t listen to me.’ So Suzanne was scared of the Doctor and, more importantly, he considered human beings below him and, if they provoked him, he would destroy them both. In fact, that’s what he says: ‘We must destroy them [Suzanne]’.

This was far too scary for children, moving the Doctor character away from a potential hero and into a potential murderer, or kidnapper at least. In the final script, it is an accident that sends the two schoolteachers and the Doctor and Susan on their journey through time and space. And the rest of the dialogue was lost also, which is unfortunate, as this is where Suzanne’s history is explained, who she was, where she came from, her relationship with the Doctor and the reason for them being on Earth in 1963, i.e. all the things we – and Carole Ann Ford – wished to know and have been a mystery for the past 50 years.

Suddenly, the Doctor calls Suzanne ‘Findooclare’. He explains that, if he let the schoolteachers go now that they had seen the ship, they would tell people about it, and, although many people wouldn’t believe them, the enemy would. It is here that parallels with David Tennant’s story ‘The Family of Blood’ start coming into the equation. It becomes clear that Susan is being hunted. The Doctor says, ‘Everywhere [the enemy] he listens. He searches for you, Findooclare… for you. His victory is not complete until he destroys you.’

It is clear that Susan is an important figure, again as the Doctor explains: ‘Findooclare would rule! Findooclare would be Queen in a world greater than any your minds could dream of. But her people are enslaved by the Paladin hordes.’

Ian Chesterton thinks that they (the Doctor and Suzanne) are both mad – and says as much – whereupon the Doctor states, ‘You would insult a Lord of the House of Doclare’, meaning him. Then Doctor Who’s greatest secret is explained away in one sentence from Suzanne: ‘[Findooclare] It’s a name he has for me. I was a baby when the Paladins attacked our world and he saved me. We got away in this machine… It was the first our people made.’

If one were to put this into context of the present Doctor Who mythology, it would suggest that ‘the ship’ was indeed a Tardis, which would make both the Doctor and Susan [Suzanne] Time Lords, maybe at the time of the Time Wars. What it concludes, answering one of the great unexplained questions of the show, is that the Doctor and Suzanne are not related and that she is simply just another companion, albeit an important one, and indeed one that feels so incredibly thankful and affectionate towards him, because he managed to save her while the rest of her race – the Doctor’s own race – perished. So the Doctor’s first ever companion is a fellow Time Lord? Yes, and an important one. If we follow the first draft of the script, Suzanne is the one who is hiding and, following ‘Human Nature/The Family of Blood’ idea, it is Susan who has taken human form to hide from the enemy, the enemy that need a Time Lord and the Tardis. So what important Time Lord was Suzanne and why did the Doctor eventually let her slip away into obscurity (in a later story ‘The Dalek Invasion of Earth’)?

The simple answer is that she may well have been the Queen – not the President – of Gallifrey, and eventually the Doctor allowed her to stay human and find love (see again ‘The Dalek Invasion of Earth’) and protect her evermore, or leave her safe until it was her time to reclaim her throne.

Newman needed the whole section about the home planet and death threats cut out. He didn’t want to set the Doctor up as a bad guy and didn’t want his past – and that of Suzanne’s – explained away, he wanted it left unknown, and it has remained that way for 50 years.

Someone Newman sent a six-page story/character breakdown to, along with a copy of the first draft script of ‘An Unearthly Child’, was Tony Williamson. Tony had written for The Avengers among other things, but decided not to take part in the series because of other work commitments. He preserved the script until his death, ten years after which his widow sold it to a private collector, whereupon it was used in research for this book.

Once the script was rewritten (with the character names changed), the six-page brief of the show, with final character names and descriptions, was sent out with the final draft of the script ‘An Unearthly Child’. And there the great mystery began: the aliens’ history had been taken out; we learn that they are exiles from their own planet but nothing else. Who is he, Doctor Who? And what relationship does Susan really have with the Doctor?

And there was the liquid gold that captured children’s imaginations. The intrigue and legend began. Of course, Newman was absolutely right to make changes and create a mystery that complemented the title of the show; however, it is fitting that only now, around the 50th anniversary of the show, we truly find out what the relationship between the Doctor and Susan really was.

The Daleks are a major part of the continued success of Doctor Who. After the introductory pilot, the first story’s viewing figures were poor – between two and three million people – which was a disaster by BBC standards. And, although 4.4 million people allegedly sat down to watch the first ever episode, the caveman story ‘The Tribe of Gum’ lost some of those viewers as the story went on. Verity Lambert confessed that the drop was the result of a poor choice of opening story. In interview, she stated that she would never have commissioned a caveman story, but the decision was not hers at the time.

However, after the first story was over, the second brought in the Doctor’s most fearsome enemies and suddenly viewing figures soared to between eight and ten million viewers. Children in playgrounds the length and breadth of Britain were shouting the word ‘Exterminate’ and Dalekmania gripped the nation for the first time.

Newman was outraged. The show had very quickly fallen into the ‘bug-eyed monster’ category that he was so keen to avoid. Lambert denied the accusation, saying that the Daleks were humans who lived inside protected casings in the future. Newman wasn’t happy, but, as the show progressed, he admitted that the Daleks were what made such an enormous success of the programme.

The Daleks were the brain child of ex-comedy scriptwriter Terry Nation, an influential Welshman (not unlike Russell T Davies, who is primarily associated with the blockbuster return of the show in the new millennium), who was lucky to write for the show in the first place. When Whitaker approached Nation through his agent, the writer was in Nottingham writing a stage show for comedian Tony Hancock. Hancock apparently joked, ‘How dare the BBC approach a writer of your calibre to write for children’s television!’

That should have been the end of it, but that night Nation and Hancock had a huge row and the writer found himself on a train back to London the following day with no job. Remembering the offer made through his agent, he called her and asked if she had turned the job down yet. She said that she hadn’t had a chance to do so. So he changed his mind. He wrote a treatment for Whitaker, who loved it, and history was made.

Although Nation came up with the idea of the Daleks and wrote clear instructions as to what they would broadly look like, it was Raymond Cusack who would design the first Dalek. His idea however, was too expensive to make, so he sat down with two other designers, Jack Kine and Bernard Wilkie, and together they designed the armoured pepper-pot much loved by Doctor Who audiences for the next 50 years.

Surely though, William Hartnell had something to do with the success of Doctor Who in the early days? He was, after all, the first actor to play the part, and his interpretation must have been most important, providing the blueprint that his successors would follow?

The Doctor was born way back in those original reports, where Sydney Newman ensured that the character would prove to be different from anything else ever created. The Doctor would be a ‘crotchety old man’ and the audience would only know that he and Susan were exiles from their own planet.

Along with Verity Lambert, Newman had another major success on his hands. In fact, when David Tennant made his final farewell as the Doctor on 1 January 2010, the Doctor is seen attending a book signing of a female descendant of a lady the Doctor nearly married when he was made human (like Susan?). When one glances at the book jacket of the lady’s book, it is clear her name is ‘Verity Newman’.

Doctor Who was a joint effort from many different talented people, not just the programme makers, and one cannot underestimate the influence of the great William Hartnell.

Hartnell was the first ever star of the show, the man who would convince the viewing public to suspend disbelief for a while and travel through the universe with him in his time machine. That gentle mocking smile, that knowing twinkle in the eye were all Hartnell’s, and many of the first fans of the show will maintain, to this day, that Hartnell was the very best Doctor Who. Indeed, he was the most mysterious. But how did Doctor Who change Hartnell’s life, both personally and professionally?

An interesting question, and one that requires a detailed answer…

‘But what sort of man is he? You must judge for yourself.’

Time Enough for Love

Robert A Heinlein