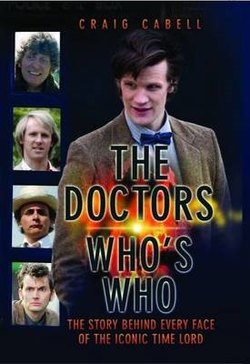

Читать книгу The Doctors Who's Who - The Story Behind Every Face of the Iconic Time Lord: Celebrating its 50th Year - Craig Cabell - Страница 15

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

PATRICK TROUGHTON

Оглавление‘Dr Who faces the awe-inspiring reality of Space and Time and with wonderful human courage… He is human curiosity personified. He must see for himself; he must go there; he must learn all there is to know.

Are we not all a little possessed of the spirit of Dr Who?’

The Equations of Dr Who

The Doctor Who Annual, 1965

PATRICK GEORGE TROUGHTON was born in Mill Hill, London, on 25 March 1920 and educated at Bexhill-on-Sea Preparatory School and Mill Hill Public School. At the age of 16, he went to the Embassy School of Acting at Swiss Cottage, London, which was run by Eileen Thorndyke, sister of Dame Sybil Thorndyke. He earned a scholarship there and progressed to the Leighton Rollins Studio for Actors at the John Drew Memorial Theatre in Long Island, USA. He was in America when the Second World War broke out. He returned to England on a Belgian ship, but it hit an enemy mine and sank just off Portland Bill, in sight of England. Troughton escaped by lifeboat and always considered himself lucky to have done so.

He joined the Tonbridge Repertory Company on his return to England in 1939 and acted there for a year. In June 1940, he joined the Royal Navy (RN) not deterred by his close escape from an ocean-going death the previous year. His first duty was protecting the coast from enemy submarines in an RN destroyer. He was then transferred to motor torpedo boats based at Great Yarmouth, where he was given his own command after the Allied invasion of Normandy. He left the RN in March 1945, but always retained a fondness for the sea.

Troughton then returned to acting and joined the Amersham Repertory Company. From there he was asked to join the famous Bristol Old Vic Company, and he appeared in Hamlet (1947–48) and King Lear (1948). He then spent two years with the Pilgrim Players performing T S Eliot’s plays at the Mercury Theatre, Nottingham.

In the early 1980s Troughton said of his career, ‘I like to play all kinds of people in all kinds of plays. I’ve got a special liking for fantasy and rip-roaring adventures with plenty of action, such as Robin Hood and Kidnapped.’

Troughton always considered himself a character actor and he cut his teeth on roles in classic Boy’s Own-type adventures. He was the character actor personified, which was why he was always very reluctant to give interviews, as he explained in a rare radio interview towards the end of his career, ‘It’s wrong [for a character actor] to promote their own character too much… the audience get to know you too much, which makes your job harder.’

Troughton’s career was long and distinguished. His first movie role was in Escape (in which William Hartnell also appeared) in 1948 and, in 1950, he was in Disney’s Treasure Island alongside Robert Newton’s infamous Long John Silver, a larger-than-life character actor who had been in the RN with future Doctor Who Jon Pertwee.

Troughton’s first TV appearance was in 1948. ‘It was the early days of TV,’ he remembered later. ‘About 300,000 TV viewers in London only… I was never relaxed in live TV.’

He may not have been, but he played many live roles for about 15 years before pre-recording came in. Unfortunately, many of Troughton’s early TV performances, along with those by William Hartnell and, to a certain degree, Jon Pertwee, no longer exist, which makes analysis of the actor’s work difficult. But many older people remember Troughton as Robin Hood. The six-part show was written by Max Kester and was recorded live at the Gaumont-British Studios in Lime Grove, London, between 17 March and 21 April 1953. Nowadays, Troughton’s grandson Sam appears in the latest BBC interpretation of Robin Hood alongside Jonas Armstrong and Keith Allen.

Some of Troughton’s other early roles included Guy Fawkes in Gunpowder Guy (alongside future Doctor Who producer Barry Letts) in 1950 and The Scarlet Pimpernel in 1956. These parts were very minor compared to his film work, which in 1955 included the part of James Tyrell in Laurence Olivier’s iconic Richard III. Although his wasn’t a major part in the film, it was memorable: being summoned by King Richard and told to murder the Princes in the Tower in a very tight two-shot, before providing a very strong voice-over during the murder scene itself. Troughton was clearly up to the job, with so much experience behind him in such a short space of time. In fact, he truly adds an additional sinister edge to the film by doing the king’s dirty work against his own free will. This wasn’t the first time Troughton had played alongside Olivier, having appeared in Hamlet (1948), which followed his own TV version the previous year.

In 1962–63, Troughton played Daniel Quilp in the BBC’s epic interpretation of Dickens’ The Old Curiosity Shop, something he mentioned as a career highlight in 1983. ‘I did a lot of Dickens… the dwarf Quilp in The Old Curiosity Shop was a big success and a part I look back on with great love and excitement.’

Diversity was the watchword of Troughton’s career and next he played the blind man Phineas in the film classic Jason and the Argonauts.

The movie opens with King Pelias, an evil dictator, receiving a prophecy from a Soothsayer regarding a golden fleece. He learns that a baby that will grow into a man will thwart him: Jason, a man with one sandal.

When grown, Jason saves a man – King Pelias – from drowning, and when Jason loses a sandal, during the incident, Pelias knows that the prophecy is drawing closer to a conclusion. Indeed, Jason doesn’t help himself. He tells the king that he is on a quest to regain his throne and kill the evil Pelias. Knowing that he could never kill Jason in one-to-one combat, Pelias tells Jason that he isn’t ready to confront the king and tells him to gather good men and a ship and prove himself first by capturing the golden fleece.

Jason and the Argonauts is a well-thought-out script with cutting-edge special effects for its day. When Jason eventually arrives at Phineas’ abode and witnesses Harpies (winged demons) stealing his food and tormenting the blind man, the film takes on a mystical edge. Before Jason obtains the advice he seeks from Phineas, he sets up a trap to capture the Harpies, which his crew perform by catching them in a huge net thrown down from the top of a ruined temple. The temple used in the scene is a real ancient temple in Italy, and the actors were given special permission to climb on it.

To create any stop-motion animation requires some level of improvisation from the actor. There are no model creatures or actors in suits roaming around during shooting, so the actor is left to visualise what is going on and act solo, with the creatures being inserted afterwards. Ray Harryhausen explained the process with regard to Troughton’s scene: ‘For the Harpies sequence I designed several “contacts” with humans. The first where the blind Phineas is fighting off the demons and we see his stick and belt yanked from him by the creatures… Both objects were attached to off-screen wires and on my signal a member of the crew pulled them away from Patrick Troughton. Later in the animation studio I would animate the models… as though they were snatching the objects.’

Jason and the Argonauts took two years and three million dollars to make, but the end result is a magnificent piece of cinema with a great cameo role from Troughton.

Several years later, in 1966, Troughton was making a film in Ireland called The Viking Queen when he was asked if he would like to become the second Doctor Who. At first he didn’t want to do it, feeling that it wasn’t the right type of part for him. ‘I was astonished that they asked me,’ he said later. He had watched the show with his children and really enjoyed Hartnell’s Doctor, but was unsure if it could continue when Hartnell left. ‘I thought it would last about six weeks after Billy Hartnell had finished,’ he said in 1983. ‘The whole concept of the Doctor going on… was quite a new idea, and one was jumping in at the deep end.’

The BBC were persistent and finally convinced Troughton who felt he should black up for the part, simply because as soon as he left the role he knew that everybody would know him as the Doctor and therefore he would be typecast.

It was Sydney Newman who brought Troughton back down to earth and shaped his interpretation of the Doctor, with a throw-away comment: ‘Do what you like with him. Play him like Charlie Chaplin if you want to.’ (Doctor Who – A Celebration, Two Decades Through Time and Space, Peter Haining, W H Allen, 1983). This appealed to Troughton, so that’s what eventually happened, but only after other ideas such as ‘playing him like a Windjammer captain’ (very tough and hardy) had been thrashed out (Blue Peter interview, 1983).

It’s difficult to say if the Chaplin idea was finally Troughton’s or Newman’s. It appears that Troughton went off the idea and Newman asked, ‘Whatever happened to the cosmic hobo?’A compromise was eventually achieved, with Troughton playing the part very clownishly to begin with, but mellowing as time went on.

He reminisced on TV magazine show Nationwide (1983): ‘First they put a wig on me and I looked like Harpo Marx, then they dressed my hair like a Beatle,’ so the zany Chaplin image was toned down from very early on.

Troughton needn’t have worried about being accepted as the Doctor. He was fondly regarded from the off, as highlighted in the Doctor Who Annual (1967): ‘Our new Dr Who is more “with it”; he is more “switched on”, more in tune with the 20th Century. There are, of course, still traces of his old personality and, characteristically, he still wears the same clothes, which are a trifle baggy on his new figure.’ So the cosmic hobo was thoroughly accepted.

The cast accepted him as well, as Doctor Who companion Anneke Wills (companion Polly) remembers, ‘We played our little joke on Patrick the first day he started. Michael Craze [companion Ben Jackson] and I ordered some special T-shirts and we greeted our new Doctor with the words: “Come back Bill Hartnell” blazoned across our chests. It was a ghastly joke, I suppose, but dear Patrick took it very well.’

Troughton remembered his three years as the Doctor with fondness: ‘Of all my… years as an actor, I think these were the happiest three years. I particularly enjoyed acting with Frazer Hines, who played Jamie [Troughton’s main companion in the series]. We never once had a cross word all the time we worked together.’

Frazer Hines confirms this: ‘For three years Pat… and I had an absolute ball together. I think there’s always room for fun when you’re working – except, maybe, if it’s Chekhov or Shakespeare – and I’ve always been a practical joker.’

Troughton got on well with all the regular cast and production crew, as he recounts, ‘Innes Lloyd [who took over from Verity Lambert], the producer when I started, and Peter Bryant were [also] great to work for. I had a lot of fun.’ (From The Making of Doctor Who, Malcolm Hulke and Terrance Dicks, Pan Books, 1972.)

Troughton enjoyed the fantasy of the show. He thought it was great that the Doctor could change his appearance, as he explained at the time of ‘The Three Doctors’, ‘We are all different aspects of the same character. Of course it’s bound to be a bit of a mystery to us, but in the Doctor’s space-time machine the so-called past just doesn’t exist.’

Like Hartnell before him, Troughton said that it was difficult to stop being the Doctor when the cameras were off, but, unlike Hartnell, Troughton’s Doctor was not a crotchety old man, but a cosmic hobo, as he explained, ‘When you’re playing a part for a long time you certainly take on some of the mental attitudes of the fellow you’re playing. Luckily the Doctor was a very jolly fellow and I just bubbled along.’

He would also say that having young children at the time – three under ten years old – allowed him to keep in touch with the part of the Doctor, as children loved the character so much. So again, like William Hartnell, there was that Pied Piper aspect to Troughton’s Doctor and not just in the pipe – recorder – he played, but in regard to the children who followed him. He mentioned the younger viewers in 1983: ‘It [Dr Who] also gave me great pleasure coming into contact with children, for if I had not been an actor I would quite like to have been a teacher. Children keep one young.’ In fact, Troughton followed up by stating that the continuing success of the show was due to new children being born.

Troughton regretted leaving the show ‘very much… but you can’t do something forever as a character actor’. Three years was a long time for Troughton to be involved in one particular project, as he confessed, ‘If I stayed with it too long, I would get stuck.’

After Doctor Who, like before, he took on many memorable roles and, to him, Doctor Who was just one in a long line. In 1983, while shooting ‘The Five Doctors’ on location in Wales, producer John Nathan-Turner and former Doctor Who Jon Pertwee spent some time convincing Troughton to attend the special 20th anniversary convention at Longleat, as Nathan-Turner remembered, ‘Jon Pertwee and I persuaded him to do it… And then he did cartwheels to get out of it… And [eventually] he said, “I’m not going to get out of this, am I?” and I said, “No!”’

It is important to note that Troughton and Pertwee were very fond of each other, as Pertwee was very keen to point out, ‘We are tremendously fond of each other, but we made out we didn’t get along at conventions because Pat’s Doctor and mine didn’t get on in “The Three Doctors”. So it was all an act!’ And a fine one too, causing all sorts of fun banter.

As soon as Pertwee had taken over the Tardis reins in 1970, Troughton was already working hard on another major project, The Six Wives of Henry VIII, playing the role of Norfolk. This re-established him in serious character roles, although he would continue to enjoy other genre roles in horror and fantasy, such as Father Brennan, the tortured priest in The Omen (1976). This was a tremendous role for Troughton, allowing him to adopt an Irish accent and pester Gregory Peck to murder his adopted son, who just happened to be the spawn of the Devil.

The Omen remains one of the greatest horror movies to this day, but, in fact, it is a typical thriller with such quality thriller actors as Gregory Peck, Lee Remick, David Warner and Billie Whitelaw.

Billie Whitelaw was terrifying in the movie and proved that the most evil person was the one who looked normal. But Troughton didn’t look that normal in the movie. He had to play a desperate priest, a man with terminal cancer who papered the walls of his home with pages of the Bible and was desperate to tell Peck and Remick the truth about their son Damien. His thick Irish accent, his deathly pale features, his inner frustration and desperation to be heard – his inner turmoil – make Troughton’s role a truly memorable one in the film, and his death scene is one of the most iconic in horror-movie history. Couple that with a haunting score by the legendary Jerry Goldsmith, and you have cinema history that is impossible to remake with any credit. Troughton had worked with Billie Whitelaw before in an episode of Espionage (1963), called ‘He Rises on Sunday and We on Monday’.

After The Omen, Troughton took a part in Sinbad and the Eye of the Tiger (1977), one of Ray Harryhausen’s last stopmotion movies. Troughton played the part of the wise man Melanthius. He had, of course, played the part of the blind man, Phineas, in Harryhausen’s classic Jason and the Argonauts (1963) before Doctor Who, so he was not offered such parts because of his connection with the show. Indeed, he played alongside Christopher Lee in two Hammer Horror classics The Curse of Frankenstein (1957) and Scars of Dracula (1970) (playing the small roles of Kurt and Klove respectively); so the role of the Doctor had no ill effect on his career at all. Troughton could still take on small, interesting roles like any other jobbing character actor.

Returning to Sinbad and the Eye of the Tiger: despite being a Harryhausen movie, the film was quite poor. It was the fourth Sinbad movie and it was clear that ideas were no longer plentiful. The over-dubbing in the film was annoying to begin with, and Harryhausen’s bony demons were a poor copy of his killer skeletons from Jason and the Argonauts over 15 years previously.

Jane Seymour is the obligatory gorgeous love interest, just as Caroline Munro was in the previous Sinbad film, The Golden Voyage of Sinbad, which starred Tom Baker (see Chapter Five). That said, the wicked Zenobia (Margaret Whiting), is an unconvincing counterpart to Tom Baker’s wizard in the previous film, who physically ages due to her deals with demons and the prince of darkness.

Although Sinbad and the Eye of the Tiger gave the appearance of being more expensive in budget than its predecessors, it was an unimaginative story that walked down tried and proven pathways with little additional imagination. So what of Patrick Troughton’s performance?

Troughton had taken part in the iconic Jason and the Argonauts, albeit in a smaller way, and so was an inspired piece of casting for this latter movie, because there were some pretty poor choices of actor for other parts.

As Melanthius the wise man, Troughton lives in a dead city on a desert island with his daughter. He starts off cantankerous and vain, but manages to muster a sense of wonder and amazement that brings a whole new dimension to the movie, albeit a third of the way through it.

While most of the cast try to dazzle the audience with their stunning good looks, Troughton settles down behind his big bushy grey beard with an ever-building sense of humour (which must have been as contagious off camera as on). One can probably see a little of the Doctor in his character, especially when an experiment he is conducting goes wrong and explodes (to his immense joy).

Sinbad and the Eye of the Tiger is Sunday-afternoon family fodder to this day; it’s just a little lazy in its creativity in comparison to other movies in the Sinbad series, and especially the Harryhausen canon.

Troughton’s love of popping in and out of familiar roles is clearly shown in his strong ties to two particular novels of Robert Louis Stevenson, Kidnapped and Treasure Island. Despite being in the classic Disney movie in 1950, Troughton returned to Treasure Island in 1977, where he played a very convincing Israel Hands in the TV series. His portrayal of the infamous swashbuckler Alan Breck in 1952 and 1956 in TV versions of Kidnapped were mentioned as career highlights by Troughton shortly before his death in the 1980s. There were some stories Troughton revisited throughout his career, Robin Hood being another one and, of course, Doctor Who, which he returned to three times.

Troughton enjoyed dabbling. He even dabbled in the soaps, taking a role in the longest-running one of the lot, Coronation Street, playing the part of George Barton in 1974. So his character actor status was fully appreciated by all sorts of casting directors, not just those associated with action and fantasy. Troughton was an accomplished character actor and Doctor Who did not tarnish that in any way.

Despite severe heart attacks (in 1978 and 1984), Troughton continued to work hard, taking on cameo roles in All Creatures Great and Small (opposite future Doctor Who Peter Davison in an episode entitled ‘Hair of the Dog’), Minder and The Two Ronnies 1984 Christmas Special. He took a more permanent role in TV sitcom The Two of Us with Nicholas Lyndhurst in 1986 (on a rowing machine in one particular scene!). He was also the first person ever to be murdered in Inspector Morse (George Jackson in the very first story ‘The Dead of Jericho’) in 1987. Troughton’s last performance was in the TV comedy Supergran also in 1987.

Patrick Troughton died on 28 March 1987, in Atlanta, USA. He was attending the Magnum Opus Con II in Columbus, Georgia. While taking part in the panel Q&A, he complained of feeling unwell and retired to his room. He suffered a fatal heart attack the following morning after ordering his breakfast and was found lying on the floor. He was pronounced dead on arrival at the hospital. He was 67.

When people discuss Troughton’s great roles, the part of the Doctor is always there, but his Quilp and Breck, even so long ago, are also considered classic performances, as is his portrayal of Cole Hawlings in the BBC six-part fantasy for children The Box of Delights. If we look at this role against that of Father Brennan in The Omen and then his roles in Coronation Street and Doctor Who, Troughton’s diversity and skill as a character actor is quickly showcased and appreciated.

Patrick Troughton was the quintessential British character actor, never staying in one place – or one role – for too long. Perhaps Doctor Who fans were initially upset by this, especially the way he would talk about his other roles with equal or more love, but they soon came to understand why Troughton was sometimes shy of public appearances and interviews. He didn’t want to give too much of himself away or for them to get to know his true character. That said, he did return to Doctor Who several times, in 1973 for ‘The Three Doctors’, in 1983 for ‘The Five Doctors’ and yet again – because he enjoyed the comeback so much! – in 1985, for ‘The Two Doctors’. This last appearance – an excellent story featuring his faithful companion Jamie [Frazer Hines] alongside then incumbents Colin Baker and Nicola Bryant – showcased Troughton’s love for and humour in the role (through one ‘dinner party’ scene at least, where he is momentarily transformed into a creature with a love of human flesh with a counterpart chef from the same carnivorous race).

All of these return visits show that Troughton had a place in his heart for the show right up until his untimely death; but let us not forget his other, now largely overlooked, roles.

Doctor Who was neither saint nor sinner to Patrick Troughton. What the Doctor has done for him is to keep him in the minds of the young forever, as the immortality of Doctor Who will keep his work alive and, perhaps, tempt some people into finding old Troughton gems on TV and DVD.

‘It now seems so long ago that I played the part of the Doctor that there is really very little I can add to what has already been written. And, of course, I’ve played so many different parts in the last forty years.’

Patrick Troughton from ‘Doctor Who Indulged My Passion for Clowning’ Doctor Who – A Celebration, Two Decades Through Time and Space

Peter Haining

Before moving on to the life and career of Jon Pertwee, I do wish to labour the fact that Patrick Troughton’s life and career is dreadfully understated. Unfortunately, the biggest culprit of this was Troughton himself, not wishing to do too many interviews. But also it is the BBC’s fault by erasing so many episodes of his Doctor Who and also destroying – or not recording – so many of those early live TV series such as Robin Hood, Gunpowder Guy or Kidnapped. In many ways, Patrick Troughton is the forgotten actor, let alone the lost Doctor. One thing I have saved to mention here is his fantastic performance as Adolf Hitler in the Gateway Theatre production of Eva Braun. This was in 1950, when feelings about the Nazis still ran high, but he did it and he did it well.

Patrick Troughton isn’t quite overlooked nowadays; he has a legacy through his family. His daughter’s son is now Harry Potter’s nemesis Dudley Dursley (Harry Melling). His son David Troughton – apart from being an accomplished Shakespearean actor – appeared in Doctor Who during his father’s time, in stories ‘The Enemy of the World’ and ‘The War Games’, also playing a more substantial role as the dashing King Peladon opposite Jon Pertwee’s Doctor in ‘The Curse of Peladon’, and Professor Hobbes in David Tennant’s excellent story ‘Midnight’. David Troughton’s brother Michael is an actor and teacher, most notable for playing opposite Rik Mayall in The New Statesman as Sir Piers Fletcher-Dervish.

The Patrick Troughton Theatre opened at Mill Hill School in 2007 to celebrate one of its most accomplished former actor students and, along with his family and many Doctor Who fans around the world, Troughton’s legacy is somewhat secured. That and, of course, the latest Doctor Who, Matt Smith, singling him out as a huge influence on his own interpretation of the Doctor.

‘For who would bear the whips and scorns of time.’

Hamlet

William Shakespeare