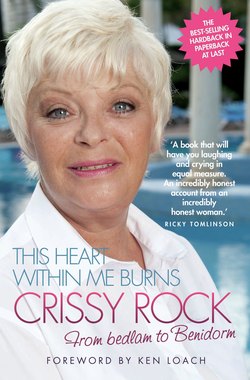

Читать книгу This Heart Within Me Burns - From Bedlam to Benidorm (Revised & Updated) - Crissy Rock - Страница 17

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеCHAPTER FOUR

DOWN WITH SCHOOL

Her lips were red, her looks were free,

Her locks were yellow as gold:

Her skin was as white as leprosy,

The nightmare Life-in-Death was she,

Who thicks man’s blood with cold.

Primary school for us was St Saviour’s on Crown Street. There’s a hospital there now. All of us went to St Saviour’s, even my dad had been there.

I won’t use my class teacher’s real name but will call him Mr Smith. He had the bushiest eyebrows I’d ever seen, and the biggest, loudest voice I’d ever heard. It was in this voice that he told us we were thick – especially me, or so it seemed. You’d answer one thing wrong and that was it.

‘Murray, I can’t believe how thick you are. You are as thick as a brick.’

And, of course, all the other kids would laugh. Day after day, week after week, every single term, I was told I was thick and eventually I started to believe it. I began to wonder what the use was of trying to learn anything. It was the same story back home; when no one else was in, Granddad would be saying how disgusting I was, and how the bad things that happened were always my fault. And then at school, Mr Smith would tell me the class’s bad results were all my fault. The verbal assault from both of them damaged me right through to adulthood. Teachers reading this, please take note.

So I made a stand: I rebelled and decided Mr Smith was going to teach me nothing. I became abusive to him and cheeky, and even when he asked me questions that I knew the right answer to I would give him the wrong answers deliberately.

He would say, ‘You are as thick as two short planks, Murray.’ Yet I knew that Mr Smith was frustrated, angry that his teaching skills were being put to the test, and wondering if he was going wrong somewhere. It became a constant battle, a war that was talked about in the playground and no doubt in the staffroom.

One day, we got a rare treat and watched a film in class about the Sahara Desert. It was a relief to get a break from Mr Smith’s monotone voice. We sat and watched the film in silence learning about how deserts were created, how the sands moved and expanded over time, and about the creatures that survived in the hostile environment, how cold it was at night, and how hot it was during the day. It was so effective that I wished every lesson could be like that.

But, when it finished, Mr Smith spoiled it.

‘Right, Murray,’ he shouted, ‘what was the name of the film we have just watched?’

(That’s how Mr Smith spoke to us, always by our last name.)

What a stupid question, I thought. Ask something about the desert or erosion or a camel even. But the name of the film?

‘I don’t know, sir,’ I replied.

‘You don’t know what you’ve just sat and watched for the last hour, you stupid girl?’

All the other kids in the class were laughing and I loathed him with all my heart.

He pointed at the screen. ‘Look at the screen; it’s there in big letters, you imbecile.’

I shook my head. I could see the words up on the screen but couldn’t make sense of them. This is why the children were laughing, they could read, but my mind was frozen and I couldn’t.

The laughter continued as Mr Smith walked over to me. He looked around at the class and smiled, revelling in his comedy act. He pointed at his temple, tapped it two or three times, grinned, then looked at me and pointed. My classmates laughed louder. The bastard knew I couldn’t read but still he persisted in humiliating me.

Mr Smith was in my face by now and I could smell his stale breath as he roared at me. ‘I confess I never really knew just how thick you were, Murray. I’ll ask you again, what was the name of the bloody film?’

He waited for an answer that never came, then he pointed back to the screen. ‘It’s there in black and white, you idiot!’

I could feel my face going red. I wanted to read the words, honestly I did, but they were making no sense; all the letters were mixed up. I could feel the tears of shame welling up in my eyes, my face flushed red.

This time Mr Smith really shouted. ‘Tell me what the name of the film is, Murray… NOW!’

I stood up and used the words Granddad used. ‘It’s your fuckin’ film, you should fuckin’ know what it’s fuckin’ called.’

The kids weren’t laughing now. Those words had never been uttered in Mr Smith’s classroom before, and I was quite pleased at the effect they had on both the class and the teacher, whose chin all but hit the desk.

‘What did you say, girl?’

‘You fuckin’ heard, it’s your fuckin’ film, you tell me the name of it.’ I pointed to the screen. ‘It’s right there in fuckin’ black and fuckin’ white.’

Mr Smith launched himself at me and grabbed me by my arm, pulling me from behind the desk.

‘Get off, you dickhead.’

‘Get out of my class, you filthmonger,’ he roared.

I pulled back from him. ‘Get off me. Don’t be grabbing me because you don’t know what your own fuckin’ film is called.’

Mr Smith was bursting at the gills, beetroot red with anger. He almost threw me through the classroom door, and frogmarched me to the head teacher. Mr Mcloughlin was a lovely man, and he asked me what I had done softly and sensitively. I hung my head as he asked me to think again about my actions. Mr Mcloughlin had taught my dad and he told me how disappointed he would be, but, when I left his office, he asked me to pass on his regards to Dad. How nice was that? Of all the teachers at that school, I only have fond memories and respect for Mr Mcloughlin.

Mr Smith, though, was not satisfied. He stood and fumed. He recorded the incident in a punishment book and then dragged me back to the classroom by my ear. He made me stand in the corridor and told me he would be back with the cane. After the bastard had made me wait at least 20 minutes for my punishment, he raised the cane high above his head. I watched him do that, then squeezed my eyes shut and gritted my teeth waiting for the contact.

He hit me across the right hand six times with that stick. On the fifth blow, I broke down and burst into tears. It felt like my hand had been stung by a million wasps. He smiled as he broke me, then delivered the sixth stroke with such power I swear he nearly broke my wrist. It was a big victory for him in our ongoing war.

‘Not so cocky now, are you, Murray?’ He smirked as he walked away.

I spent more time outside Mr Smith’s class than I did in it. Sometimes, after 20 or 30 minutes he would shout out my name for no reason.

‘Murray… outside now.’

‘What for, sir? I ain’t done not’n.’

‘No, but you will soon. Now get out.’

So I’d have no choice but to leave the class or another visit to the head would result.

Inevitably, I hated school. Mr Smith was definitely the worst of the teachers, but most of the others were little better. If you couldn’t keep up or got a question wrong, they would rap a ruler across the back of your knuckles and think it was such a hoot. The rest of the class would crack up laughing, just thankful that it wasn’t them.

Nothing from lessons seemed to sink in with me. At times I wanted to learn, I really did, but then my spirit would be broken by an abusive teacher with a strap or a ruler, and I would just think to myself, ‘Fuck them… fuck them all.’

In any case, my head was full of different things. I had enough problems to worry about at home. For one thing, Mum was still not well. Nan would help me get ready for school, walk me up to 3C to collect Brian and Ian, who’d still be in bed, while Mum would rock backwards and forwards in her dressing gown on the sofa. She would whisper gently that we didn’t have to go to school today and smile and stare at the walls. I’d be quite happy and put a little breakfast together for Brian and Ian, then take them out of Mum’s way while she nursed my youngest brother, David.

This routine worked fine, and I’d get Mum to write a little note for the school saying that she’d been ill through the night and had overslept. It seemed quite easy at the time and of course I didn’t have to suffer the humiliation at the hands of certain so-called teachers who couldn’t teach a dog to bark.

Occasionally, the school board would turn up at the house. If that happened, either Nan would help us to get to school for a few weeks or Mum would rally herself. That worked for Ian and Brian, but by now I’d had enough of being abused at school as well as at home and at the first opportunity I would be off out the school gates.

Poor Mum couldn’t cope at all. Thank the Lord for our nan who did what she could. She set us chores to help Mum who at times could barely drag herself out of bed. Before long, Brian and I were doing most of the housework. We did most things for our mum, like cleaning up and washing – which we were quite happy to do – but inevitably there was the odd argument.

Early one morning, Brian and I were in the kitchen arguing about whose turn it was to wash up. We were shouting at each other when Mum seemed to appear out of thin air. She casually took the bowl of dishes from the sink and chucked them through the window. Broken crockery and glass, splinters of wood, knives, forks and spoons sailed through the air as if in slow motion and crashed down into the street three storeys below. Panic-stricken, I looked out through the broken window convinced someone had been killed by our broken dishes. Thankfully, no one had been walking by.

‘There,’ she said. ‘You don’t have to argue now, our Brian and Christine, because there’s no dishes.’

She smiled, turned and walked away again as silently as she’d appeared.

***

When no one is in the house Granddad still plays the choking game.

‘Please stop, Granddad, please stop.’