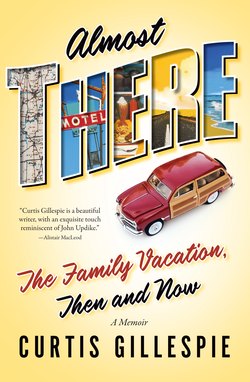

Читать книгу Almost There - Curtis Gillespie - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление1

The Memory Well

IN THE SUMMER of 1973, my parents announced our family was going to take a trip. A trip, mind you. They didn’t use the word vacation because, I suspect, it implied things they weren’t willing to commit to, such as our safety and comfort. The plan was that in mid-December eight of us—mother, father, and six children aged three to thirteen, five boys and one girl—were going to pile in our faux-wood-panelled Ford Country Squire station wagon and drive through the middle of the continent from Calgary to Mexico City, then turn around and come back along the west coast. Six weeks. Eight thousand kilometres. Through the high snowy passes of Montana and Utah. The emptiness of Arizona. The heat of the central Mexican desert. I still find this next fact hard to square with a memory of sane and loving parents, but once we got past Utah we were going to camp. Every night in a three-room eighty-pole oilskin canvas cave that when rolled up was roughly the size and weight of a small refrigerator. It took four of us two hours to put up and almost as long to take down, and had once caused my father to suffer a perforated hernia. I loved that tent, but I hated it, too.

We set off on a cold and gloomy December morning. The canvas tent and most of our luggage was roped to the roof of the car and covered with a tarp. The trip started as every trip did, whether it was to the local mall or Mexico City—a jostling for seats, superior position, bragging rights. No single seat was really that much better than any other, but we fought over them because they were something to fight over; usually the fighting was nothing but shoving and pushing, though often it escalated into rabbit punches, eye pokes, head butts, and nut chops. The monarch’s throne was the space between the middle row of forward-facing seats and the set of facing jump seats at the back; the throne wasn’t very comfortable, but there was room enough for just one child, which made it the only spot really worth having (and this was long before the days when seat belts were mandatory; in fact, I don’t remember if that old wagon even had seat belts). At thirteen, as the oldest child, I believed myself entitled to the throne, but I was slow getting to the car and when I tried to rough up my brother Keith for the spot, he and my brother Bruce ganged up on me and gave me a double nipple twist. I ended up in the jump seats with my sister, Janine. Sitting perpendicular to the direction in which the car was moving always made me feel queasy. I hated the jump seats.

We were smart enough kids, the six of us (though not nearly as smart as we thought we were), but we had zero notion that by travelling in this way in 1973 we were personifying the zenith of a significant historical trend. In fact, we were living in the last great gasp of the family car trip as a major North American cultural expression, an expression crank-started into life fifty years earlier by the introduction of automobile travel as a recreational pursuit and brought into full flower after the Second World War when the buying power of the middle class increased such that cars were widely available and families could afford them. Families could also afford to take a vacation; prior to the war, workers’ rights began to crystallize, and legislated paid vacation time, once unheard of, was becoming commonplace. The combination of paid holidays and being able to purchase a station wagon one could load to the roof (and above) was, in many ways, the starting line of what we now understand as the family vacation.

Which was what we were up to, even though, as mentioned, we were probably already living in the latter stages of the automobile trip as the predominant family vacation mode. It was history itself we were taking part in, though it was hardly history of a Hegelian stamp, since you might say the jury is still out on whether the automobile will ultimately be seen as progressive in humanity’s run. Not that we’d have known, or cared, anything about Hegel, history, progress, or the zenith of the automobile trip; we just figured we were going on a really long drive. My hope, though (no matter where history comes down on oil and the automobile), is that there will always be room for the road trip in the family vacation. It’s so rich in possibility. I know that driving to Mexico and back created something larger than a simple collection of experiences and destinations for our family; it created memories and moments so strong, so singular, that we saw our family as unique. It gave us a vision of the larger family project at work, particularly upon reflection in later years, of course. There wasn’t much conscious articulation of it when we were all sitting around watching TV a few months later, as if twelve-year-old Bruce said to nine-year-old Conor, “Hey, that trip really helped me understand and put into words the nature of our family dynamic, don’t you agree?” Yet, at some level, it did precisely that; spending six weeks in a car driving to Mexico and back became a key component in the shared baseline knowledge of what we were as a unit, of how we related to one another, of how we were moving together through time—reflections that have stayed with us as a family decades later.

Orvar Löfgren, in On Holiday, wrote about making a discovery one day, as an adult, down in his basement, where he found “an old holiday album, which I produced as a twelve-year-old. It describes a family trip across Sweden and starts with a pasted-in map where the route is carefully drawn. Snapshots, admission tickets, hotel labels, and picture postcards document each step, along with the author’s running commentary. It documents a vacation and shows the project ‘our family,’ an institution that became very visible during those summer months of intensive interaction.”

I love that notion of the family as a project, suggesting as it does that it takes time, that it involves construction, that it requires thought and craft, that it speaks to an ongoing evolution. The family as project helps create a family that can talk, be together, and travel together. Whether we realize it or not, our family vacations are key building blocks in the creation of a family, of a “project.”

Whatever piece of the family project Mexico was meant to be, however, all we knew, as kids, was that we were heading towards an intensely foreign place known to us mostly through the cliff divers of Acapulco we saw Saturday afternoons on The Wide World of Sports. My delicious nightmares leading up to the day of departure were of scorpions, rattlesnakes, and getting lost in the empty, wobbly-hot Mexican desert.

As we pulled out of our cold, gaunt northwest Calgary suburb, my mother lit a cigarette, turned around and did a head count to avoid a repeat of a trip to Edmonton a year earlier when we were an hour down the highway before realizing we’d left two-year-old Matt at home playing in the basement. The goal for the first day of our trip was to make it at least as far as central Montana. Seven or eight hours of total driving would be a good start. We’d been driving for half an hour, approximately six-tenths of one percent into the journey there, when Bruce, eleven months younger than me, shouted from the middle seats. “Pass me a comic book,” he said. “An Archie.”

I reached into the huge cardboard box between my feet. Our mother had spent the previous three months collecting thousands of comics and puzzle books to help occupy us during the slog ahead. She’d kept them locked in a closet leading up to our journey, under the not unreasonable premise that there’d be no point to having them in the car if we’d already read them all. Bruce and I had tried to break into the closet a month earlier. Somehow Mom found out and we were sent to confession at St. Luke’s daily for two weeks. Every one of us had been anxious to dig into the stacks. I pulled out an Archie for Bruce and held it aloft to show him who controlled the means of distribution.

“Give it to me, you loser,” he said.

I flung it at his head as hard as I could, the pages flapping like the wings of a buckshot-filled bird. He ducked, picked up his comic, and started reading. I looked back at the box. So many comics! It was a stroke of genius on my mother’s part to have hoarded them. I riffled through the stacks and found a Spider-Man, my favourite.

Ten minutes later, I was in trouble. I’d been concentrating too hard, reading too close, with the comic too near my face, and this, combined with the side seating and the relative cold of the back seats, brought the car sickness up from the bottom of my stomach to where it pressed against my windpipe. I swallowed hard to keep it down, but a tiny spurt of burning liquid came into the back of my throat.

“We have to stop,” I said thinly.

My sister, seated across from me, looked up from her comic.

“We have to stop,” I repeated.

“Dad! Curt’s gonna hurl! Stop the car!”

My mother looked back. “Oh, for heaven’s sake,” she said. “Just stop reading for a few minutes. You’ll be fine.”

“We just left the goddamn house,” said my father. “Why didn’t you throw up before you got in the car?”

Janine clambered a bit up onto her seat, and then with no fanfare my throat opened. The contents of my stomach splashed into the middle of the comic box, covering the entire library in partially digested Froot Loops and Cap’n Crunch. Janine put her hand to her mouth and nose, and watched my sickness run itself out across my chest and pants.

“Oh, gross!” she said, scrambling across the throne into the middle row of seats. “He puked! He puked right into the box of comics. They’re covered. All of them!”

My father pulled over. Everybody piled out onto the side of the highway. We were still less than an hour from home. My mother stood with her arms crossed, smoking a cigarette with great melancholy as she watched my father create a minor ecological calamity by hurling the entire swampy box of bloated comics into the snowfilled ditch. There was no such a thing as the environment back then. My mother dropped her cigarette on the ground and extinguished it with the toe of her boot. Her months of hoarding and protecting and planning were ruined. Everybody hated me. On the way back to the car, my brother Conor punched me in the kidneys from behind, doubling me over. “Loser,” he said.

“You’ll all have to find something else to do in the car now,” my mother said. “And it’s a long way to Mexico City and back.”

Nobody would sit with me in the jump seats, where the smell of vomit would stay sharp for days afterwards. I had to strip down to my underwear, but my father refused me a change of clothing on the grounds that my duffel bag was on the roof rack buried somewhere under that canvas tent, and there was no goddamn way he was untying that goddamn tent an hour into our trip. I hated that tent. My father hadn’t had a cigarette in three years, but he was smoking again two hours into the trip. As we neared the U.S. border I sat alone in the back, despised by everyone, myself included. The U.S. border guard said nothing about the naked shivering boy hugging his knees to his chest in the back of the station wagon, but I could see him peering at me when we pulled away. I think he wrote down our license plate number. It was, indeed, a long way to Mexico City and back. And that Spider-Man was the last comic book I ever read.

*

The family vacation and the idea of the family vacation have always held considerable interest for me, a fascination that has to do, I suppose, with an abiding curiosity about families in general, how they form and disband, how they communicate or don’t, how they operate or don’t. I’ve written about family from the day I started writing and will continue to do so, I’m sure, until I lay that pen down, and you can’t think about the family without thinking about the family vacation; I can’t, at any rate. Families are obviously infinitely and uniquely complex, which means their vacations are likely to be the same.

I’m fortunate enough to recall the family vacations of my childhood with actual fondness, and although these memories are no doubt rimed with nostalgia (as every happy childhood is), there was an objective love and goodwill at the core of my upbringing. Which is why this book will perhaps not resonate with those who grew up in less-than-nurturing environments (although I hope it does) and who were forced to go on trips with people they felt no affection towards. Happy families are not the most fertile writerly soil, for as Tolstoy so famously wrote in Anna Karenina, “Happy families are all alike; every unhappy family is unhappy in its own way.” But if I can be so presumptuous as to reframe Tolstoy’s words, I would say that every happy family will vacation in its own unique way (ready as they are to share any and all experiences together), whereas unhappy families are all alike on vacation (turned inward and anxious to be elsewhere). At the risk of sounding naive, I happen to think that families are not always or necessarily the seething angst-ridden prisons of alienation that art and the therapy industry typically make them out to be, but that sometimes they are both a stimulus and framing device for understanding and intimacy and unity . . . sometimes even on vacation.

The family vacation as I have experienced it, and as I view it symbolically and metaphorically, makes me smile. Am I lucky? Yes. Am I deluded? Possibly. For this, I can only blame my parents, who raised six children in a spirit of love and patience, even if they spanked us, grounded us, and failed to push me hard enough as a child to become the professional soccer player I know I could have become with even just the occasional dose of belligerent sports-parent hectoring. I grew up in a small house jammed to the rafters with human beings, not just because we were a family of eight, but because our parents were well-liked by our friends, which meant there were always an extra couple of bodies hanging around at any given moment. Ours was a disorganized, fun, energetic household, and as you’d guess, our vacations were about the same. The further my wife, Cathy, and I advance into raising our two daughters, the more astonished I am by what my parents achieved: the raising of six children, all of whom still like one another, none of whom have ever been in jail, and all of whom are, if not well-adjusted, at least not misanthropically maladjusted. I once told a poet friend of mine that my mother used to read to us at the dinner table after supper on many nights. Sometimes it was The Hobbit. A couple times she might have even read Shakespeare; I know my dad liked Shakespeare, even though he didn’t finish high school (my dad, not Shakespeare). My poet friend has never let this family detail go, and to this day shakes his beard and goes on about how my family was, in fact, the most distorted of all because we got along and exited our childhoods with minimal emotional scar tissue.

Growing up, I had garden-variety teenage concerns—girls fascinated and terrified me, I didn’t have my own bedroom or privacy of any sort, I was short and pudgy, my roster of friends was not that long or reliable, school sucked. But my family life, far from exacerbating these problems or alienating me further, in fact saved me from getting swallowed up by whatever troubles I had. And whenever we went on vacation, I can truly report that I went with a spirit of excitement and anticipation (which would usually prove to be warranted), not dread or opposition. That’s not to say that every vacation was a peak experience or one fantastic and warm family outing after another. Hardly. I was often underwhelmed with our destination. I was frequently driven to violence by the immature antics of my siblings in the car (which I obviously never instigated). I was frequently carsick. We spent a lot of our vacation capital visiting relatives. But despite all this, going on holidays with my family was never something I rebelled against. It was, most of the time, a hell of a lot of fun.

When you stop to think about it, though (which I often have, sometimes in the middle of a family vacation moment going pear-shaped all around us), going on vacation with your entire family is hardly the way to guarantee that you will have, in the first place, a good vacation, or, in the second, a happy—or even a monosyllabically communicative—family upon your return. In fact, I’m sure we can all recall examples of family vacations that seemed to conclude not just as periods away from home but as harbingers that the family itself was aboard the Titanic and all that was left to do was to get pickled and wait for the iceberg.

This, luckily, was a rare experience for me, because I have always believed the family vacation was about so much more than the activity or destination. Certainly, the family vacations we took in my childhood were enjoyable for the most part, even usually great fun and adventure, but they have also been central to my ability to recollect memories of growing up, of what it was like to be part of my family, and to form conclusions and understandings about the nature of the family structure. They also helped me, and still help me, understand who I am. Memory is the wheel on which we are forever turning the raw material of our experience, and the family vacation supplies a great deal of that raw material. From that memory wheel comes insight. And because these times in our lives are so amplified—these family vacations when we are separated from the structure and distraction of daily life—they bear great meaning and influence.

The family vacation is a deep well; it’s one of the best tools we have to interpret our past and present, and peek into our future. The kids, a tent and sleeping bags, some sunscreen, the open road—just another road trip, you say? Hardly. The meaning of our memories can and will shift, alter, and morph, but memory will always be an instrument we use to define our families, ourselves, our relationships. There are many situations and moments we use to create the movie in our heads of what our family is, of what “family” is, but the clearest often come from the family vacation. It’s specific in its time frame and is often conducted in sharp contrast with our daily lives, which means our senses and attention are heightened. The family vacation is a way to bank family memories, to colour in what might otherwise be broad outlines. As Julia Harrison writes in her book, Being a Tourist: Finding Meaning in Pleasure Travel, “All those who travel for pleasure, no matter what name they apply to themselves . . . unfailingly want to gather valuable and enduring memories.”

Furthermore, the family vacation is a highly fluid socio-cultural institution. As the culture in which families exist has changed, so the vacation has adapted to fit or reflect that culture. The family vacation, in both structure and meaning, has evolved as society has evolved, although one or two seismic shifts in the nature of the family vacation have, I think it’s fair to say, moved the needle on the broader culture. How families choose to vacation is a clear expression of who we are, and the nature of the family vacation tends to reflect, and sometimes even predict, societal change.

The family vacation, then, is central to how individuals and families define themselves, how families form, and most particularly how these intensified periods in the life of a family continue through the years to replenish our individual and shared memory pools. “Family memories offer us a way to make sense of our family history,” writes Susan Sessions Rugh in her book Are We There Yet? Vacations are significant events in the lives of adults and children: we remember them keenly for good reason—because they help tell us who we are and how we fit into our family. The vacations I went on with my family when I was growing up may have been fun, but they were also much more than fun; the nuance and richness of what it all meant has only gradually been revealed through adulthood and the raising of children. I understand much better now that the manner and quality of vacation a family experiences together are a symbol for many things besides a trip’s stated raison d’être (which is frequently interesting enough in and of itself, of course). It can also be viewed theoretically, moving into the philosophical sandbox of thinkers like the French philosopher Jean Baudrillard and his ideas around the interpretation of experience, which are relevant to how we interpret the experience of the family vacation. To boil a dozen works of philosophy down to a few sentences (which I am only too happy to do), Baudrillard says we live in an ongoing state of “hyperreality,” that we utilize and then inevitably begin to prefer representations of reality rather than reality itself, and that the human condition is so impossibly overwhelming that our experiences can’t help but devolve into mere encounters with simulations of reality—simulacra, he calls them—encounters that we end up preferring to reality. We’d rather visit New York–New York hotel in Las Vegas than actually take on New York’s crime, grime, and complexity; we’d rather consume pornography than deal with the complications of real sex; we feel stronger emotional ties to characters on TV than we do to the flawed and inconsistent people in our own lives. And so on.

Sounds odd, I know, but once you’ve visited Disney’s various themed experiences, been to a dude ranch, or seen the “island” Royal Caribbean built to replicate a real tropical island, you might think Baudrillard is on to something. This is a counterpoint to what Orvar Löfgren calls the stance of the “anti-tourist” and the obsession with locating “authentic” experience, or that of the “post-tourist” who has given up trying to find new and authentic experiences, and has joined in with the throng going to Disneyland, knowing it’s fake but taking their fun with a heavy dose of irony. There is no such thing as inauthentic experience for the post-tourist, because even an encounter with an utterly fabricated site—a fake island, say, or Disney’s Swiss Family Robinson tree house (a fake of a fake, since it was a fictional experience and the “tree” holding the tree house is made of steel, concrete, and stucco)—will nevertheless yield insights into contemporary culture.

Authenticity comes up again and again in travel and leisure literature, but what, precisely, do we understand by the word authenticity, anyway, as it relates to our travel experience? There’s no easy answer for that, and much depends on what you’re looking for in the first place. We all know that a “tourist trap” is something contrived and manufactured and best avoided, but what if we are looking for tourist traps? What if we like tourist traps? Don’t we then want to find the most authentic tourist trap? Of course, there are times when even being sure of what you want won’t help you find it, given that much of today’s marketing is not just manipulative or misleading (we expect that) but blatantly fraudulent. Recently in both Spain and my home province of Alberta tourism marketing bodies were found to be using photos of exotic locations to stand in for home base. Alberta used a beach in Northumberland, England, of all places, to represent Alberta’s natural beauty; Spain used a photo of a deserted Bahamas beach to stand in for its crowded Costa Brava.

So the question What does it mean for a family to go on vacation? is certainly not as simple as it might first appear. We want our children, and ourselves as parents, to have as much access as possible to what we view as authentic, real, genuine experiences and places, however we define that, though we also want our children to gradually be exposed to the world’s complexity, part of which is undeniably the way in which our leisure is manipulated by corporate interests. We want our children to touch and know the world as it is, but we also want to keep them physically safe and allow their emotional innocence to exfoliate naturally rather than have it torn away painfully and too early. These tensions are constantly at play, so to speak, in the family vacation. Furthermore, since we’re on the subject, if perhaps we are unfortunate enough to lack “authentic” connections with one another in the first place, then what’s the point of seeking authentic experiences on a family vacation? Or can one help create the other? We need to ask these probing questions of family travel because the answers say so much about who we are and how we find the shared experience that allows us to communicate inside the family compact.

Why do families travel? Are parents trying to create bonds they are failing to make elsewhere? Are we broadening our children, or setting them up for dissatisfaction with their lives back at home? What is the value of travelling together as opposed to staying home together? Do we truly believe we are providing our children with valuable experiences, or just exposing them to the world so as to provide a baseline for future individual explorations? Or is it just about having fun? There is research being conducted today around the role of the family vacation in the creation of the family unit overall, and one of the terms in use for the family vacation is the “memory-making process.” The family vacation, as we can see, is an ongoing memory-creation operation that’s never going to be straightforward: It involves taking a multifarious and usually ill-disciplined unit—the family—sending it on a logistically complex mission—the vacation—and asking it to secure a poorly defined and highly subjective outcome—“fun.”

That doesn’t sound so hard, does it?

*

Our first major stop on our Mexico-or-bust trip was Salt Lake City, where my parents wanted us to see the Mormons and the Tabernacle Choir. Why they did, I’m not sure. Perhaps it had something to do with the catholic and Catholic nature of our upbringing. My mother was, and still is, a devout Roman Catholic. My father respected my mother’s faith, but he was an avowed agnostic who used to stand in the bathroom on Sunday mornings, church day, with shaving foam on his face and his razor in his hand and answer our theological queries with things like, “How the hell am I supposed to know if there’s a God. Go ask your mother.”

Or it could have been the profligate nature of the procreative impulse on display in Salt Lake City; my mother might have reckoned it would do us good to see that Irish Catholics weren’t the only people that bred like bacteria. My mother was pregnant for forty-five of the first sixty-four months of her marriage, and on the day of my sister Janine’s birth my mother was a twenty-six-year-old woman with five preschoolers in the house. Much later in life I remarked to my friend Rich, who was also a friend of the family, how astounding it was to me that my parents hadn’t killed off one or two of us out of frustration and simple expedience. “How do you know they didn’t?” he said.

Salt Lake City was a place of great mystery to us, and its shrouded, misty December climate seemed suited to that feeling. I had trouble imagining who would want to live near a salt lake: what was the point of that? We toured the Tabernacle Choir, and Brigham Young University, and learned about the pilgrimage to find religious freedom. It made an impression, to be sure, but then our mother told us that some Mormons believed a man could have more than one wife. We kids absorbed that as best we could, and one or two of us simply looked our father’s way for help as to how we might interpret this. He said nothing, just offered his characteristic sly grin and then raised his eyebrows suggestively. My mother slapped him on the shoulder. We piled into the car and got back on the road.

In 1924, the renowned British essayist and travel writer Hillaire Belloc (who once walked across the western United States to visit his future wife) wrote a piece entitled The Road. “The Road is one of the great human institutions because it is fundamental to social existence,” he wrote. “The Road moves and controls all history.”

Belloc may have written those words nearly ninety years ago with some confidence, but he could hardly have known how prescient they were, particularly in relation to North American history. His thoughts on the connection between man and road coincided with something of a sea change in the national psyche which allowed the common person to believe that travel for leisure purposes was not just possible, but morally acceptable. Elmer Davis summed it up in 1932 when he wrote that the “pioneer conditions that made indolence suspect and leisure unknown discouraged the habit of traveling for pleasure . . . till good roads were general. There was not enough fun in it to make it worth while . . . Then suddenly, the automobile came within reach of every one. There were immense distances to be covered and a machine capable of covering them.”

Davis was broadly correct, but I think his words have particular resonance for someone from the western part of North America; in our own early family travels we had farther to go to get somewhere. It was that simple. On the wide and endless prairie where I was raised and still live you could drive for hours and hours, stop, get out of your car, look around, and be hard pressed not to conclude that you’d forgotten to put the car in gear back home. I have no doubt that in choosing to go to Mexico and back in 1973, my parents were not just trying to do something different and unusual for their children, but also that they simply had no choice but to go far away in order for us to see something far different. The almost genetic need to cover vast distances has, to my observer’s eye, less purchase on the subconscious of the eastern North American because history and geography have conspired to create a denser, more tightly concentrated web of sights and destinations worth seeing in the east. Within two hours’ drive of Washington, DC, you can, for instance, reach most of the sites central to America’s formation. Within two hours’ drive of Edmonton you can reach places that look about the same as what you’d find if you drove two minutes from Edmonton; there is precious little of historical interest within two hours’ drive of my home, unless you are a student of the fur trade, Native history, or the North-West Mounted Police, and even less of geographical interest, unless you are an aficionado of the prairie landscape (luckily I happen to find all of the above quite compelling).

But none of this was of any consequence to the middle class until the automobile became widely available. John Rae, writing in 1971, concurred with Elmer Davis on the middle-class leap to the automobile. In The Road and the Car in American Life, Rae tells us that it wasn’t until the advent of an automobile readily accessible for nearly every class of citizen that the notion of an actual “vacation” for all was thinkable. Travel for the purposes of pleasure and recreation was a novelty as the 1920s dawned; by the 1930s it was not novel at all, largely due to the affordability, mobility, and control the automobile gave those without a summer house in the Hamptons to escape the pressures of the Upper East Side. Going on a vacation with the family was suddenly not just possible, but convenient and affordable, although the trickle-down effect for the masses didn’t hit until after the Second World War.

It was a trend that would not stop for decades and which only began to abate with the advent of cheap air travel and the gasoline crises of the 1970s. In 1971, the year Rae published The Road and the Car in American Life (and when my parents were probably subconsciously hatching the idea for our epic family car trip), he reported that nine out of ten families took their family vacations in a car via the highway. It’s important to point out—because it’s crucial to understanding the evolution of the family vacation—that the development of the American automobile industry was from the start pursued by people with a mass market in mind; this was the opposite of the European auto industry. Manufacturers in Britain and Germany pursued auto development as a purview of the wealthy. Henry Ford, conversely, expressly stated that his dream was to create “a car for the great multitude.” His dream came true. Even in dire circumstances, car ownership was possible; in The Grapes of Wrath the Joads may have had to escape to California during the Depression, but they were able to do so in a car.

There may have been times along the way to Mexico that we looked like a bunch of Okies, too, with eight of us jammed into that wagon and with most of our earthly possessions roped to the roof.

*

It was in 1956 that President Dwight D. Eisenhower signed into law the Federal Aid Highway Act, which was the plan to change the highway system from one of semi-anarchic toll road state construction to a federally controlled Interstate Highway system. It was essentially from that point forward that the family car trip became the vacation idiom of the average family; the creation of the Interstate corresponded with increased postwar economic power (more families could afford cars), increased industry advances (cars could go faster and were safer), and increased amenities along the way (more motels, gas stations, and restaurants, not to mention better tourism facilities to handle the travellers). In short, Ike built the highways when people were willing and able to travel on them in great numbers (although the Interstate was, as many a book has noted, hardly an unqualified success: maintenance and repair was radically underfunded; critics felt freeways leading into cities cut off and therefore quarantined low-income areas from upscale neighbourhoods; there was widespread corruption in the highway construction industry). In 1955, Los Angelenos protesting against Eisenhower’s plan labelled the increased auto pollution smog, which was the first time the word had been applied to carbon emissions in America (the word was first recorded in 1905 in London, England, to describe a mixture of smoke and fog).

The massive upgrade in the highway system brought change everywhere. The motel industry developed in lockstep with the travelling population, becoming more convenient and consumer-friendly, attracting families with children-stay-free offers, swimming pools, free breakfasts for children under certain ages, playgrounds. Fast-food outlets changed to accommodate family car travel, as well, perhaps the most iconic example being the A&W drive-in, a car-friendly approach that was rapidly adopted by numerous chains and independents.

Of course, the car and its corollary industries were everywhere. During this period, one-sixth of all Americans produced, sold, serviced, or drove motorized vehicles for their livelihood, and certainly this was the case in Canada, as well, which has always featured the auto industry as a huge component of its economy. In fact, it was even the basis of our household economy. My father ran his own business, Calgary Glass and Trim, and although he repaired and recovered furniture now and then, his biggest customers, by a wide margin, were the car dealerships in town. Most of his business revolved around car-windshield repair, seat-cover repair, and (here’s a nostalgia item) vinyl-roof repair—the canopy, the halo, and, my favourite, the glorious landau, which was a covering of the rear third or so of the roof, designed to make it appear as though it were a convertible. He regularly removed and applied these vinyl roofs, and I can so easily winch up from my memory the smell of the glue he used, a smell that delivers me whole to my youth and my father’s workshop.

My siblings and I often spent time in his workshop helping him—or so we thought—although I wish now I’d gone more often. In retrospect, it feels as though in pulling off those vinyl roofs we were also peeling away some of the symbols of the auto industry’s excesses, even that my father was, in fact, part of an industry soon to have the lid yanked off its trash can full of problems. Car travel might well have reached its peak in the sixties and seventies, which meant that just before the oil embargo of 1973 the family vacation was the epicentre of the North American family’s love affair with the car, that moment when romance, cost, and efficiency met and group-hugged, an embrace that lasted until mass air travel, OPEC, and the environment broke up the party. Susan Sessions Rugh, in her book Are We There Yet?, termed this period—roughly from the end of the Second World War to the mid-seventies—the “golden age” of the American vacation.

All of which means that the family vacation as a common notion, even as a kind of universal expectation, could be said to have started with the advent of mass automobile travel on American highways. An efficient means of transportation, which was also cheap, became available through large-scale production to the bulging lower and middle classes. After the Second World War, when North America was flush with confidence and economic growth, roadways sprung up to provide corridors on which to use these vehicles. Suddenly, and it almost was sudden, millions of families could afford to travel as a family. Travel they did, and so did we.

*

By the time we got to Arizona, the car was beginning to feel more like a space capsule we’d been trapped in for months as opposed to a means to an end, as if the trip was not about seeing the world, but was simply a way to spend six weeks sitting in the car. My parents had done their research, though. They knew the kind of thing we’d like, and they knew about the Meteor Crater just outside Flagstaff. As we drove to it, they pumped us up. We were incredulous. An outer-space meteor hit the earth? The crater’s a mile wide and six hundred feet deep?! It hit fifty thousand years ago?!! When we pulled into the parking lot, the six of us kids, especially us four oldest boys, were so hyped we sprinted to the edge of the crater. My mom and dad ran after us, leaving Matt and Janine straggling behind in the middle of the parking lot.

“Hey,” my dad shouted. “Hold up, you little brats!”

They were terrified, I’m sure, that we were just going to go careening over the lip of the cliffside. Had we visited the Meteor Crater on our way back from Mexico City instead of our way down—in other words, after another month’s worth of driving, fighting, throwing up, getting lost on Mexican back roads, and an incident with a whip—perhaps they’d have egged us on. Yeah, there’s a great swimming pool right over the lip, you guys. Just jump right in.

Half an hour after we’d arrived at the Meteor Crater, my mother and sister were strolling around the crater’s rim, enjoying the heat, the brilliant sunshine, simply being out of the car. She’d sent my father off with the five boys. Mom and Janine stopped at one of the designated viewing areas and peered into the 600-foot-deep crater, taking in its awesome scope, perhaps recalling what she’d told us all earlier, that the impact explosion was 150 times greater than Hiroshima.

“Hey, look,” said Janine, pointing to the distant centre of the crater. “There are people down there.”

My mother peered deep into the crater. Her radar must have gone off, because she slotted a quarter into the viewing telescope and trained it towards the centre of the crater, half a mile away. Seconds later, she let it drop. “Gerry!! Gerry. Oh my God! Gerrrry. Helpp!”

My father came running over from the interpretive centre, where he’d been occupied showing Matt a display about the crater’s mineral-debris field. He’d assumed that when we left him, it was to head back to where our mother was.

We were quite happy, the four of us, me, Bruce, Keith, and Conor. There weren’t any fences once you got past the formal viewing area, and it really hadn’t been that hard a climb down to the crater floor, though some tricky descent work had been required. There seemed no reason not to explore the crater. After all, what was the point of visiting the thing if you couldn’t go to the middle? I wanted to stand there and look up and out. Who wants to be on the periphery?

The four of us didn’t eat that night. After the rescue, which necessitated an emergency scrambling of half the Crater staff on duty that day, we drove away in humiliated silence. As the oldest, I got the blame. I always got the blame. I hated being the oldest. Everybody else got to play the younger-sibling card, and my parents fell for it every time.

“I swear,” I said in the car. “I swear I didn’t know there was quicksand at the bottom. I swear, Mom. Do you think we’d have gone down there if we knew that?”

The logic of my argument didn’t sway her. “Quicksand!” she kept repeating. “I mean, quicksand. Didn’t you see the signs?! They were everywhere. What if you’d stepped in it? Disappeared?!”

“You know,” said Bruce. “That’s actually a myth. You don’t sink in quicksand.”

My mother turned around and glared at us, lips tight. It may have been the angriest I had ever seen her . . . to that point (the qualifier being necessary since we still had 80 percent of the trip remaining). But to this day I insist that I did not see a single warning sign as we crossed the lip or clambered down the cliff face. Okay, yes, we saw them at the middle of the crater, but by then we were already there, and the ground felt solid enough, so what would have been the point of turning back then? What a waste of effort that would have been.

Mom and Dad, and Janine and Matt, ate KFC that night in Flagstaff, and the smell of it—the thirteen secret spices, the fries, the gravy—was almost too much to bear. It wasn’t right. It was unfair. We pointed out that it was, technically speaking, child abuse to starve your children.

“We’re so hungry,” we said. “We have to eat. You can’t not feed us. We’re going to die.”

“Good,” said Janine.

“I don’t care if you’re hungry,” said my mother. “You should have thought about how hungry you were when you were walking through that quicksand.”

“I wasn’t hungry then,” said Keith.

My mom shot us a look that made us shut up. Who could blame her? She was probably wishing we’d found the quicksand. We spent the night in agony, stomachs growling, the scent of KFC everywhere. I have not eaten KFC since.

*

The early seventies was a tricky time to be making a trip like the one my parents had orchestrated for us. I doubt they would have set about planning it had it been even a few months later, given that it was in mid-October of 1973 that OPEC announced it was ceasing oil shipments to countries that supported Israel in the Yom Kippur War, which meant the United States, Canada, most of western Europe, and Japan. OPEC also used their power to begin hiking the price of oil, so not only was gas in short supply, it cost more. Gas was about 30 cents a gallon in January of 1973 and had tripled by year’s end.

This was no small burden for my parents; my father’s business was steady but unspectacular, and my mother had only recently returned to part-time work. We were not exactly poor, but my mother shopped for cheap cuts of meat and had a friend at the bakery who put aside half a dozen loaves of day-old bread a couple times a week. We lived in a small bungalow in the Calgary suburbs, and I recently brought about dropped jaws and bulging eyes in our two teenage daughters, Jessica and Grace, when I told them I did not have my own bedroom until I left home for university.

The oil crisis had an impact, albeit a minor one, on our trip, but it had a much greater effect on car travel in general for many years to come—and therefore on the family vacation. In fact, it’s fair to say that the fall of 1973 may have been the last time when a family could look upon the cross-country car trip with virtually no guilt or worries other than those of individual family logistics. Following the autumn of 1973, the world of oil security has never been the same; these pressures increased throughout the seventies and early eighties, with another oil crisis in 1979 brought about by the fall of the Shah of Iran. There has also been a radical increase in the number of cars on the road, which has had an impact on traffic safety (which has been negatively affected even further by deteriorating highway infrastructure). The rise of environmental awareness has also changed the thinking of many families who otherwise might have hit the road for a few weeks to see where the wheel turned.

By the time we’d left on our trip in early December 1973 there were some gas lineups and the speed limit had dropped to 55 mph; this was perhaps the first time since the end of the Second World War, nearly a full generation, that there was an inkling that an automobile trip was anything less than the most convenient and carefree way for a middle- or lower-middle-class family to take a vacation.

In many ways, the golden age of the gas-powered automobile is not only over, but died a long time ago; we’ve just yet to fully accept the inevitable. Of course, we are still reliant in many key ways on the car, but less so than we were a decade ago, a trend that will be even more pronounced a decade from now. And who knows if alternative fuel sources for cars, such as batteries or hydrogen, will allow us to fully recapture our traveller’s imagination. Even the automobile industry’s core incubator group—young teenage men—are increasingly getting their thrills from different places, such as electronics and other technology. A 2004 story in the Los Angeles Times revealed that in the decade from 1992 to 2002, the percentage of males aged sixteen and seventeen getting their driver’s licenses dropped from 52 percent to 43 percent.

The sixties and early seventies—through the automotive confluence of the cost, safety, environmental innocence, and overall convenience—may well have been the apex of the family car vacation. This mode of vacation has become less predominant since then, given the rise in cost of gasoline, the rise in insurance rates, the introduction of mass air travel, the increased cost of lodging and food along the roadway, the deteriorating state of the highways, all combined with what has become an often crushing sense of crowdedness on the roads. Sometimes it seems as if, against all logic, there are more people moving than stationary. Who are all these people? I often ask myself now while driving on teeming highways. And where are they in such a rush to get to? A long drive on the highway used to be a pleasure; now it has the air of a chore.

This sense of congestion is not solely about the number of cars on the highway, but is also related to the hassle it has become in many major urban centres to actually get to the highway. By 2000, almost 80 percent of the population in Canada and the United States lived in urban areas, and of that number close to two-thirds lived in the suburbs, meaning that fully 50 percent of us live in a suburban environment. Suburbs have metastasized to monstrous degrees. More and more commuters live farther and farther out from the urban core, and use the suburban freeway system to get to work and get home. It has become a trial to find the open road, let alone travel along it. Travelling from one major city to another, particularly along the eastern seaboard, is not so much a highway drive as a series of hops between vast suburban links and ring road freeways.

All these factors speak to why the family vacation as expressed through the long-distance car trip already has an air of nostalgia to it, a Leave It to Beaver smell of a long-gone world we now choose to romanticize, but which we would have trouble re-creating even if we wanted to. Robert Sullivan, the author of Cross Country, predicted the demise of such trips in an article he wrote recently in the Los Angeles Times. The summer driving trip, meaning the “pack the kids in the car and set out for the West or the East or possibly the Grand Canyon trip,” is under threat. “It’s been endangered before,” he wrote, “especially during the first energy crises in 1973 and 1979, when people spent good portions of their vacation lined up at the gas station.” But today, referring mostly to the crowded attractions and highways, he concludes, “The death of the car-bound family vacation feels real to me.”

I know I’ve considered attempting a re-creation of the Mexico trip my parents took their children on, but the truth is that it would be impossible to re-create even if we decided to try it. The vehicles of today, for one, are simply that much more comfortable, and I can assure you that a significant portion of the antics we got up to in the car were due to sheer discomfort. And we simply couldn’t allow our children to not wear seat belts, the lack of which was central to the free-for-all that ruled our car on the way to Mexico. There are more people on the roads today, more people at the sights worth seeing, simply more people period. And at the sights worth seeing, the level of bureaucratic people management has altered the nature of the family vacation experience, so that events and encounters are now more sanitized, more packaged—pre-experienced, as it were—so that we are too often informed beforehand, by aggressively cheerful “interpreters,” what we are supposed to feel and understand and take away. Of course, today we would have our own experiences, unique to us, memorable episodes in tune with our times. Of that I have no doubt, and it would be a good thing. But to consider the continental car trip as a way to reconnect with what our parents did for us is to indulge, I fear, in a kind of nostalgic and fruitless search. Such reconnection must, it feels to me, be performed through memory, not mimicry.

*

In exploring the nature and history of the family vacation—how it’s evolved, what it means, how it shapes us—it’s fair to say that I’ve researched principally those areas that seem most applicable to my life and time. My take on the family vacation will also be less than comprehensive for two other reasons: First, the family vacation is still, as already alluded to, a relatively new phenomenon. Second, there is a shortage of data on the subject. The tourism studies field has grown in the last couple of decades, to be sure, which is understandable, given that tourism is such a vast global enterprise. But even as late as 1985, John Jakle opened his book, The Tourist, by saying, “I present this book as an argument for renewed scholarly interest in tourism.” Jakle has lived up to his end of the bargain: He has also written scholarly studies of the motel, the gas station, and the roadside fast-food restaurant.

The need for renewed interest is peculiar, though perhaps it has begun to happen since Jakle published his book in 1985. The level of tourist activity certainly warrants it. In 1999, Orvar Löfgren reported that 7 percent of the world’s total workforce was employed in the tourism industry by the mid-1990s, an industry in which $3.4 trillion is spent every year. By 2020, Löfgren noted, it is expected that 1.6 billion of the planet’s 7.8 billion people will take a trip abroad. These would appear to be significant numbers, but even as recently as 2003, research on the subject appeared to be lagging. Nancy Chesworth, a Canadian academic, wrote in the International Journal of Consumer Studies that, “A review of the literature on the impact of the family vacation experience in the fields of consumer issues, tourism, hospitality, home economics, family studies, psychology and sociology indicates little research reported to date. Furthermore, there has been little published in this area of study in the last decade. This seems unusual considering the high degree of importance placed on families and on vacations by societies around the world.” In addition, she found a lack of research on the impact of the family vacation on single-parent families, marital relationships, gender differences in terms of vacation choices and satisfaction, individual family members, the positive and negative impacts on children (including academic achievement and sociability), children’s reaction to holiday experiences, and the well-functioning family versus the mildly or seriously dysfunctional family.

Pretty much everything, in other words.

It’s perplexing that there are not think tanks and university departments specializing in the family vacation. If there is one, I wasn’t able to find it. As Jakle wrote in 1985, “The study of tourism, like the study of recreation generally, has not been recognized by most professions as a respectable field for scholarly inquiry. Apart from the bias against leisure inherent in the work ethic, the supposed superficiality of touristic experience has weighed against serious study.”

In the course of my research, I did find a book called The Nuclear Family Vacation, which initially elicited the satisfaction of finally having found something directly related to my own research, until I read the jacket and discovered that it was about a husband-and-wife team touring the world’s nuclear weapons production sites. There was also Christie Mellor’s The Three-Martini Family Vacation: A Field Guide to Intrepid Parenting, which I confess I did not read, primarily because I had already long ago endorsed what seemed to be its central thesis. There are academic books devoted to the family vacation; Neil Carr’s Children’s and Families’ Holiday Experiences, and Susan Session Rugh’s Are We There Yet? Rugh notes that the family vacation “fits squarely into the study of the history of tourism” but that the literature has focused on “authentic experience” without taking into account how family travel could alter that experience.

As for arts and culture, there have been many investigations into the family vacation over the years. A fine minor-chord road-trip story is Alice Munro’s “Miles City, Montana,” and although it’s not particularly heartwarming, Munro does capture, with her standard impeccable prose and insight, some of the strange pressures of being car-bound for long periods of time. We will, of course, always have the subtly realistic adventures of the Griswold family in the National Lampoon Vacation series. The creator of those films, John Hughes, who also made films such as Ferris Bueller’s Day Off, Home Alone, and Planes, Trains and Automobiles, got one of his first breaks writing satirically about the family vacation. His story, “Vacation 58,” not only ended up securing his employment with National Lampoon, but it became the inspiration for the first Vacation movie. Vacation 58 is a funny saga of one family’s road trip to Disneyland in 1958, replete with the station wagon, the cross-country drive from Michigan to California, an aunt dying en route, a father falling asleep at the wheel, a father driving off a cliff, a father robbing a motel, a father forgetting the dog tied to the bumper and then driving off, a father running from the law, a father pulling into Disneyland to find it closed for repairs, and a father snapping and hunting down, then shooting, Walt Disney.

Chevy Chase did seem ideally suited for the role. Yet despite the cornball comedy of both the story and the movie, the inherent satire did have a serious point to make, which, for me, is that “arrival” is overvalued and that a more measured approach to the journey itself is of value.

Possibly there is a shortage of fine writing on the subject because most of our artistically gifted and creative writers are simply too busy writing stories of misfit outsiders coping with alienation, loss, sexual jealousy, and the betrayals of their past. Perhaps writers and artists just can’t be bothered with the family vacation’s perceived and sometimes real sentimental overtones. But here’s a question: If you really do enjoy going on vacation with your family, and you really do think it makes you closer as a family, and if you really do think it’s important to say so, then is that sentimental? Why can this not be meaningful? Is it because drama constitutes art and happiness lacks drama? Maybe it’s just that most of our talented artists, writers, and thinkers were unlucky enough to have parents who didn’t take them on family vacations, thereby consigning them as children to summer holidays consisting of nothing but sitting in their rooms with the door closed reading book after book after book, ruining their eyesight, and dreaming of the day when they could escape their non-vacationing families, and get busy writing searing accounts of misfit outsiders coping with alienation, loss, sexual jealousy, and the betrayals of their past.

What all this adds up to is that, despite the fact that tourism is a huge part of the global economy, despite the fact that a high percentage, possibly even the majority, of this tourism is conducted by families, and despite the fact that family vacations are part of the core matter of self-definition of both the individual and the family unit, there has been disproportionately little serious study or art about the family vacation. This gap is surprising, since the family vacation is not peripheral but central to our understanding of the family construct. Recently, one or two researchers have begun looking at the family vacation from this point of view, such as the husband-and-wife team Sarah and Joel Agate, who conducted much of their research while at Clemson University in South Carolina. Their work is principally rooted in American history, but it’s revealing nonetheless. Speaking at the Vacation Matters summit in Seattle in 2009, they noted in a joint presentation that there was no historically significant record of the family vacation prior to the American Civil War. Families simply did not take vacations, for a variety of reasons, the most obvious being that most people were either poor or slaves. Not only that, there was a relative lack of focus on vacationing as a family, even among families who could afford it, largely due in the United States and to a lesser degree in Canada to what we might call a Puritanical hangover. People mistrusted the very idea of leisure, since there was a country to build and wilderness to tame and colonial barriers to overcome. Diligence was next to Godliness, and the Puritans of both the pre– and post–Civil War era were beholden to both. What chance, in this atmosphere, did the family vacation have of emerging, let alone thriving? The upper class travelled as families, but that didn’t really count: their whole life was a vacation.

After the Civil War, a middle class began to emerge, the Reconstruction Era ensued, prosperity increased, travel increased, and new modes of transportation emerged, which allowed for some, but not much, family travel. Around the turn of the twentieth century the still rather embryonic middle class saw the earliest signs of labour rights—meaning, among many other things, legislated holidays—and this had an inevitable trickle-down effect to the working class. African-Americans were seeing small gains in prosperity. Immigrants were settling and adapting.

By the time the First World War ended, the working class witnessed entrenched time off actually getting passed as legislation, though this was still often only expressed as the maximum number of working hours per week. Still, it was the thin edge of the wedge and it wasn’t long until vacation time was a concept and a reality that both worker and employer saw as the norm. When the Depression hit, it was, ironically, becoming more common for the family vacation to be seen as, if not a universal right, then at least a common expectation. Just prior to the Second World War, in fact, a recommendation for mandatory paid vacation for all workers was put before the US Senate. It failed, but it did create a sense of widespread acceptance that “the vacation,” paid or unpaid still to be determined, was something a worker could reasonably expect.

Of course, the family vacation has through time often been an expression of a society’s vision of itself. In the immediate post–Second World War era there was a newly felt freedom, the expansiveness of victory, and a relative level of affluence, all of which brought about a vacation mode wherein families of nearly every stripe piled into the big station wagon and travelled enormous distances, staying in motels, often driving halfway across the country simply because they could.

Yet the conservative, rather uniform nature of the family vacation during this period was also in many ways a reflection of the conformity of the time as exemplified by McCarthyism, and by a society shaken by the Kennedy assassination and shattered by Vietnam. The family vacation was also slowed, oddly, by feminism. As women increased their agency, went back to work, and had children according to their own desire to do so—developments that may have slowed the family vacation but which sped the development of our species—it became harder for a family to coordinate long vacations. Not only that, the Agates noted, the sexual revolution made it less fashionable for women to advocate for family togetherness.

And then came mass middle-class air travel. The increasing ease and declining cost of air travel made the international family vacation a much more likely possibility in the seventies and early eighties, and although mass air travel may have hampered the car trip, it positively killed the Atlantic-crossing industry. The phoenix that rose from those ashes was the cruise industry. They had to do something with all those ships. The cruise industry began with obsolete luxury liners, but soon enough it saw the value of catering to families. Today, there might be no aspect of the tourism industry more constructed around the family vacation, and increasingly the intergenerational family vacation, than the cruise industry. (And I’ll speak more to the historical details of both mass middle-class air travel and the cruise industry further on.) It took a century—roughly from 1850 to 1950—for the family vacation to go from being the exclusive purview of the wealthy to becoming, as Orvar Löfgren called it, a fully democratized institution. It’s now taken half that time again for the family vacation to become such an accepted cultural institution that no one even imagines today that it might have been our grandparents who fought for mandatory holiday time.

The social and anthropological history of the family vacation is evolving, too. One of the themes I want to explore throughout the book is that of safety versus experience. Although strongly shaped by personal observation, my belief is that the family vacations children grow up to remember fondly and/or vividly and which become part of family lore (and which therefore help us define ourselves, our families, and our place within those families) are achieved only by wrapping both arms around something we can’t embrace; namely, abandon. A disregard for outcome, if you will. You must plan for the unplannable, and the best way to care is to not care, to—at the risk of being sued—not prize safety over experience. Bear with me.

We baby boomers and immediate post baby boomers are obsessed with preparation, mapping, detail, specialization. Our culture wants certainty, guarantees, a return on our investment. And it appears we are now applying these approaches to the family vacation. Well-planned, organized, safe, a sound investment—we’ll get our money’s worth and the activities will warrant the effort—but predictable, homogenous, managed. The Disney Cruise?! Is this what we want from the family vacation? It’s the holiday equivalent of the gated community . . . and sometimes we holiday in a gated community. But don’t we want grist for family lore? Adventure? Fun? Danger? Hair-raising experiences served up by blithely oblivious parents? Will we find that on a Disney cruise? Franz Kafka once wrote that you needn’t frantically chase the world in order to find it, since it would “present itself to you for its unmasking” even if you chose to just sit at your desk and be utterly still and silent. And so it is with the family vacation . . . well, except for the sitting-still part. Simply the act of being together will open the world up to you and allow you to define it through family—the world that is your family will unmask itself with or without grand plans, with or without great sights and peak experiences. The value created by the family vacation, its long-term familial meaning, will not necessarily reside in whether you got on all the rides you wanted to at Disneyland, or whether you got the table by the window every night on the cruise. Observing and existing in each moment together—accepting instead of grasping, as Kafka is essentially saying—is the fertile soil from which memories and meaning will grow. Abandon. Risk. Accept. Of course, you will be forgiven if you choose not to put your faith in Franz Kafka as the patron saint of the family vacation, given that his most famous story is about a man who wakes up one morning as a giant cockroach.

*

The road trip is an institution that has sometimes resulted in parents wishing they could be committed to one, and it’s hard to predict how it will evolve. There are the obvious environmental issues, although that is less about the vehicle than what’s fuelling it. Whether it’s hydrogen, battery power, even biomass fuel, families will still need ways to get from one place to another on their holidays. A more environmentally friendly fuel source might well fuel a resurgence in the road trip. The bigger question for me around the future of the road trip might be the creation of individual solitudes within the vehicle. Now that children have iPods, MP3s, iPads, and most significantly, movie centres that fold down out of the ceiling or the headrest in front of them, there is simply less chance for spontaneous interaction, less opportunity for something to happen, good or bad. Spending ten hours in a car will result in tedium somewhere along the way, and so whatever you can do to alleviate that can’t be a bad thing. It’s just that creating an impermeable bubble around each and every one of us may not be the answer. That bubble of distraction will occupy our children, to be sure, but it also signals to them that the journey is to be endured rather than considered.

Perhaps that’s why I can say we knew, even as kids, that our Mexico trip was significant. We didn’t have the words, but we understood it had meaning from the day we left until the day we arrived back home; especially once we were back home. Furthermore, home eventually became a fluid continuum rather than a specific physical structure, since that trip was part of what helped us understand that wherever we gathered as a family was our home, and that the support and togetherness we shared as a family was also our home.

Not that there weren’t times I would have loved to have escaped that car. And I know I wasn’t the only one. At one stretch my father drove seventeen hours. Halfway through that day, Keith turned from his spot in the throne and with no warning, delivered a wrecking-ball head butt directly onto my unsuspecting skull. I was briefly dazed and left with a throbbing headache for the next couple of days.

“What!” I half-shouted, trying to scramble back to retaliate, before my father shouted back at us to stop horsing around.

“He head-butted me . . . for no reason!”

“I’ve got a reason,” he said.

“I don’t give a damn about who did what,” said my father. “Stop horsing around. Do you want me to stop the car?”

I glared at Keith. “You’re dead. What’d you do that for?”

“Because I wish I had a comic to read right now,” he said.

Even though there were no comics to read, we made it through that day, and the days that followed in which there was still so much to come. There was Keith finding a dead baby hammerhead shark on the beach at Mazatlán, which he somehow persuaded my parents, and the American border guards, and the Canadian border guards, to let him bring home for show-and-tell at school, even though it had rotted badly by the time we got to Calgary. And then there was Mom, jumping up off her towel on the beach at Puerto Vallarta, shrieking at the top of her lungs, utterly hysterical, because she saw sharks in the water.

“Where?” said my dad, staring out over the water once we were all ashore.

“There,” she said, pointing. “Right there! See them?!”

My dad gazed out. “Pat,” he said. “Those are dolphins.”

She didn’t say anything more, but sometimes I’ve wondered, given the stresses involved in that trip, if she wasn’t screaming out of giddy hopefulness instead of terror. Who would have blamed her? Which was why it was so mystifying to me when my parents turned around less than a year later to buy a ratty old school bus and convert it into a long-haul recreational vehicle.

But I’ll come to that.