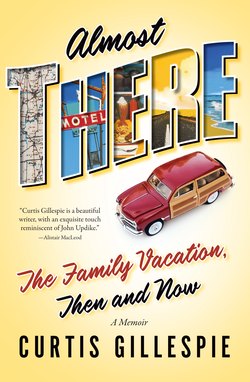

Читать книгу Almost There - Curtis Gillespie - Страница 12

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление2

The Great Outdoors

THE GILLESPIE FAMILY of 4232 Dalhart Road, circa 1975, was not poor in the strictest sense of the word: the family’s six children were clothed, fed, and in school. Still, we didn’t have wads of cash to throw around for frivolous expenditures like the latest toys, new ball gloves, haircuts, food. We ate out about once every four years. It was all about hand-me-downs, do-it-yourselves, and “I don’t care if you don’t want to use your brother’s old hockey equipment, and I don’t care that you think it smells like an armpit. If you don’t want it you can walk down the street and see if there are any other families that might want to adopt you.” I’m speaking hypothetically, of course; none of us played much competitive hockey. My mother and father were, however, parents of epic patience and resourcefulness who could have, and probably should have, been running the country; it would have been easier on them and better for the country. Ours was a small house for a family of four, let alone eight; for most of my teen years, my “bedroom” was a corner of the basement that I turned into a room by hanging a bedsheet from the rafters; it was a cross between a Moroccan yurt and the set of Midnight Express, depending on the state in which I kept it. As for privacy, well, that was like some foreign custom we’d heard about, but couldn’t imagine experiencing.

Our relative lack of affluence growing up was no hardship I recognized, resented, or even gave much thought, but it did mean that our early family vacations were usually low-budget. Or no budget. This meant camping, even though it has to be said, up front in the interests of full disclosure, that we were not one of those families deeply in touch with nature, who hiked regularly, who got out into the woods and mountains at every opportunity. Yes, we did the occasional hike, and we made it up to Banff National Park every now and then. But we were not the outdoorsy types. There were various reasons for this, chief among them that my mother liked plumbing. Communing with nature at that level never appealed to her much, and frankly it didn’t much to me, either. Whenever we hit a campground that had running water and indoor plumbing, she always seemed to cheer up and view camping as not so bad, really. I’ve since done my share of long hikes and roughing it in the bush, but I would still pick a decently equipped campground over the backwoods experience any day. I don’t know what that makes me, but what it does not make me is an outdoorsman.

We never journeyed too far away on our short camping trips around Alberta. We camped at Elbow Falls, just outside Calgary, or at Gull Lake, north of Red Deer. These were short trips, but in my memory they were some distance from home, journeys we had to plan for, pack up for, bring the tent, and generally just be organized about (to the degree that we were ever organized). I don’t think we camped much at these spots after I was about ten or twelve years old, but our early trips remain evocative for me, a true removal from home and our life there. Part of it was that we called it “a vacation,” which instantly gave it a meaning it wouldn’t have otherwise had. We had so little money when I was in elementary school that I’m sure my parents called camping at Gull Lake a “vacation” so that we could at least tell our friends we’d done something over the summer break.

But looking back, it seems clear to me now that what made our early camping trips worth remembering was the tent, the same one we would eventually take to Mexico; it may have been a beast, but it was a magical beast. The thing was gigantic and like no other tent I’d seen before or since. There were different rooms, caverns, corners, places to hide, folds from which to leap out and frighten a sibling, a hundred different smells, a separate room for the kids, a “living room,” our parents’ room, a front awning that always acted as a kind of water basin when it rained. It was both a curse and a temple, the kind of tent that for some reason my imagination wants to give a trapdoor leading to the underworld. A lack of plumbing may have prevented us from camping more, but the primary reason had to be the tent. Yes, it may have been a child’s portal, but it was also so daunting a proposition to set it up that I think my dad had to gird himself for days and weeks beforehand just to get in the proper mindset. It was so monstrously heavy and bulky and finicky that it made any trip—one night or ten—something that required full emotional commitment, not to mention a few days of Marine Corps physical preparation. Remember, we’re talking 1970 here. This was not a tent made of the lightweight waterproof fabrics of today, with their hollow, high-strength aluminum poles. Putting up one of today’s tents is a breezy five-minute stroll compared to the full-pack, army-boot, abusive-drill-sergeant swampy day-hike that was the erecting of that tent. It was not just a nightmare to put up, but I’m sure once it was up my father never slept, consumed as he must have been by nightmares of having to take it down. There were hundreds of poles of differing lengths, none of them attached by the interior elastic of today’s tents. They were heavy suckers, too, capable of braining you if one dropped on your head during decamping. Thick skin-shredding twine, attached to the four corners of the eternally useless rain guard, had to be regularly uncoiled and recoiled from many metres away. The tent itself was made of oiled canvas that through years of wear and tear had lost most of its ability to repel water but none of its ability to stain your clothes, leave streaks on your skin, integrate and return odour, and resist folding. It was a solid material, probably an eighth of an inch thick, and was so stiff that folding it, and keeping it folded, was like trying to fold thick rubber; you could do it, but unless you literally stood on it until the moment it was roped, it would spring back into some new, shapeless and utterly demoralizing version of itself. It was a kind of freestyle fabric origami, though by the time we’d been at it for an hour or so, it veered closer to Noh drama, a silent, haunting tale of frustration (and repression, surely, given my father couldn’t swear nearly to the degree I’m sure he wanted to, with six impressionable children looking to him as a role model).

Yes, our tent was a portal to a different experience, a family experience, but putting that beast up and deconstructing it afterwards was always a kind of test, a passage of a different sort, one in which our patience, and particularly my father’s, was taken to the limits of human endurance. You might think I’m joking, but I’m not. Compressed into its so-called “packed” state, it would have easily crushed a small dog or disabled a young child had it toppled from the roof of the station wagon.

Our camping trips today, with our two girls, are a mixture of the farce of yesteryear and the discomfort of an aging body lying on a rocky surface with crawling ants. We do insist on camping occasionally, and it often turns out to be fun, but as often as not, it’s more of an exercise in “teaching our children” something outdoorsy (what that is, precisely, I’m not sure). This was compounded in recent years by tossing a deaf dog with bladder problems into the mix, and into the tent—a small and light tent, I should add. Who says we can’t learn from the past?

*

Given that camping has long been, and still is, a vacation choice for so many families, it’s somewhat surprising that the formal history of camping is not that long. You’d think that camping out would have been something started pretty much the minute we dragged our knuckles off the ground and learned to walk upright. I suppose the difference is that when you didn’t really have any other options but to live outdoors you couldn’t really call it camping. Neanderthal man did not come home from a hard week of hunting and gathering to suggest to his wife and the little Neanderthals that they should get out of that smelly, dank cave and trek a few miles across the Serengeti (which you may be surprised to learn was not then known as the Serengeti) so as to pitch a mastodon-hide tent and roast meat over an open fire for a few days. That wasn’t a holiday, that was daily living. I can hear it now: “Dad, you said we were going to do something fun. That’s not fun. We might as well just stay home. That sucks.” At which point the Neanderthal dad, in time-honoured tradition, would have responded that that was just as fine with him and he’d be perfectly happy to stay home and get some work done on the cave painting, only to witness the intervention of the mother, urging family unity, reiterating that the family that vacations together evolves together. (It occurs to me as I write this that it’s entirely possible our original family tent was, in fact, not canvas but a mastodon hide, passed down from generation to generation, and evolutionary adaptation to evolutionary adaptation, absorbing every smell across the millennia, until it finally arrived at a garage sale where my father immediately recognized it as the only campsite dwelling fit for his children.)

Camping as we know it today only became a leisure pursuit once people had leisure to use, so perhaps it’s no surprise then that camping did not come into being as a pursuit until the decade or so prior to the First World War. The founder of so-called recreational camping—as opposed to the Cro-Magnon or Civil War survival variety—is generally acknowledged to be Thomas Hiram Holding. He wrote the original Campers Handbook in 1908, and many have written about how his understanding of how to live in the outdoors came from having crossed the plains of the United States with his parents in 1853. He was also a dedicated bicyclist and often rode and camped around the UK, and in fact wrote a book entitled Cycle and Camp in Connemara. Historians have said that it was this very trip that led Holding to create the Association of Cycle Campers in 1901, which had thirteen original members. It was the inaugural meeting of that association that led to the founding of what is today called the Camping and Caravanning Club.

Holding had hit upon something. Just five years later his organization had over five hundred members and modern camping was effectively born. Camping clubs sprang up all over the UK, and there was soon a breakaway club, led by Holding, that ditched cycling and devoted itself strictly to camping, though they did rejoin a few years later, only to then join with another group in 1910, all of which was then singly known as the National Camping Club. That membership was listed at 820 campers in its initial year.

Real world events soon intervened, of course, but after the First World War, camping picked up again as a leisure pursuit. It’s worth remembering that camping at that time was essentially a novelty pursuit of the wealthy; the lower and middle classes still did not possess organized or formalized workers’ power or rights, and such things as paid days off were still to come. So although camping, as the leisure pursuit we might recognize today, was formally initiated during these fin-de-siècle years, it was not a particularly radical movement. The lower and middle classes didn’t own cars or land on which to camp. North American camping at this time was almost certainly of the pioneering or homesteading variety, borne of necessity rather than leisure or desire to get back to the land.

In the years between the wars, camping continued to grow in popularity. One of the principal camping clubs of the UK at the time, the Camping Club of Great Britain and Ireland, had Sir Robert Baden-Powell—the man who started the Boy Scouts—as its president. The Second World War interrupted the growth of camping, although in Britain many sought to escape German bombing by going to the countryside; fascinatingly, this very well may have been one of the progenitors of camping as a family pursuit (although most fathers were off at war). Mothers and their children, wanting to escape the horror and danger, fled to the countryside; many of them had to camp because they were not wealthy enough to own second homes.

In the years following the Second World War, camping truly began to grow, particularly as a family pursuit. By this time, workers’ rights were becoming more entrenched and, helped by the rise of the automobile, the good highway system, and many thousands of new campsites in the national parks, camping exploded as a cheap and accessible family pursuit. By the 1960s, it would be no exaggeration to say that the family camping trip—piling into the car, tent on the roof, hitting the open highway, finding a national park, setting up camp, and hanging out for a week—became the norm for the lower-and middle-class family vacation. (Caravans and trailers experienced rapid gains in popularity during this time, as well, but I’ll discuss those further on.)

That was then, but what of now? Martin Hogue, writing for the Design Observer in 2009, noted that the Kampgrounds of America—the KOA to most of us—had five million visitors at its sites across North America, and that there were 113,000 federally managed campsites in the United States and 166,000 campsites in various state parks, as well as a virtually uncountable number in private facilities. But, writes Hogue, modern camping displays a strange contradiction, in that it is “defined and serviced by an increasingly sophisticated range of utilities and conveniences, and yet marketed to perpetuate the cherished American ideal of the backwoods camp.” In other words, we like to think we’re roughing it, but, really, we’re not. There was certainly no sophistication to our camping in the mastodon-hide tent, however; it was anarchy, pretty much like every day at home—a scramble for cereal at the picnic table, a frenzied rush to get a wiener on a stick for dinner. And there’s no sophistication in our camping today with Jess and Grace; there’s a primitive cast to our dinners, eased only by the presence of a slosh of wine in a cheap plastic cup.

But what Hogue is talking about is part of the larger narrative of today’s vacations, including family vacations, a phenomenon that I think is increasingly peculiar to our era and to relatively rich and cocooned westernized populations. We want authenticity, but we also desire comfort and security, which, again, reflects the matrix of safety versus experience. Camping sits at the intersection of the competing desires for safety and experience; it offers a gateway to the natural world, to a simpler existence, to a better understanding of and sympathy towards the planet and our fellow creatures—all fine and desirable things—yet so many of us want all this but with good plumbing and WiFi. Most of us, myself included, have become, in some way or another, acolytes worshipping at the altar of Gear. We want great gear, high-end gear, the best gear. Waterproofed, Velcroed, leathered, Gore-Texed, and micro-layered to within an inch of our lives, we set off into the wilderness in our SUVs and ATVs for an authentic back-to-nature experience . . . and if something bad happens, well, hopefully we’ll still be within cell range. If not, the GPS locator will help the rescuers to find us. We remain shocked when, every year, someone dies after getting lost in the backwoods or attacked by a cougar or skiing on an out-of-bounds slope. Well, that’s what’s supposed to happen in nature. Life in the natural world is nasty, brutish, and short, and the surprise is that it doesn’t happen more often.

But it doesn’t happen more often because we’ve tamed it to our will for the most part. Which is why camping, particularly as a family exercise, can be fun and inexpensive—the reasons for its popularity with families—but which most of the time cannot really be classed as an authentic journey into the natural world. At least not the way we camp; I think my daughter Jessica would revolt if she had to spend more than a day away from her hair straightener. Hogue notes ironically that a “campsite” in any major park today ain’t what it used to be. “Each ‘lone’ campsite,” he writes, “functions as a stage upon which cultural fantasies can be performed in full view of an audience of fellow campers interested in much the same ‘wilderness’ experience. Who in the camping community has not experienced a degree of gear envy at the sight, on a neighbouring camp, of a brand new Primus Gravity II EasyFuel stove (with piezo ignition), a Sierra Designs tent, or a Marmot sleeping bag?” KOA rents out permanently parked Airstream trailers, which means “campers” don’t even have to bring any equipment.

Little wonder then that the things we used to have to do just to stay alive when camping—find wood, chop it, draw water, clear a site, hunt for food—are now, says Hogue, nothing but a series of “almost spiritual rituals intended to reconnect the camper with what has been largely lost.” Now, instead of clearing a site, chopping wood, and finding water, we show up at a campsite, park the car, pitch lightweight tents, grab some food at the camp store, hook up our electricity, light up the propane stove, and set up our patio chairs.

In other words, we’re just playing at it.

Not that there’s anything inherently wrong or immoral about that, though it’s interesting to remember that campgrounds were originally created to protect nature from campers as much as campers from nature. It’s ironic that so many of these sites we consider “outdoorsy” actually serve to separate us from nature. Many of today’s larger campsites have conveniences such as water taps, electrical outlets, toilets and showers, all of which make “nature” something of an abstraction. We’re separated from a visceral sense of its power and mystery. Hogue relates a sad incident, reported in the wider media, that occurred in June 2010, in Arkansas, where a flash flood at a large campground led to numerous deaths, including six children under the age of seven, all of which underscored “crucial historical shifts within the culture of camping itself: an increasing lack of awareness of potential danger, and an implicit trust in the protective confines of . . . the campsite and the resources at hand.”

So what’s a family to do? Take the children on a safe back-to-nature holiday, where there is no or minimal risk (though, as the Arkansas disaster illustrates, there is still some risk), or do we seek out something as close to nature as possible, a worthwhile goal in a digital age that increasingly distances children from the natural world they might not even know they occupy. It’s no accident that a considerable amount of advertising in today’s media universe trumpets the desire to get back to nature or participate in the natural world. Vehicle advertising and naming, for example: Tahoe. Outback. Ram. Mustang. Sierra. Highlander. Tacoma. Yukon. Outlander. Cougar. Bighorn. Lynx. Sequoia. Tracker. Trail Blazer. Most of these gas guzzlers are as close to being celebrations of the natural world as Three Mile Island. The inherent contradiction and complexity of camping and the family vacation is that it’s getting harder and harder to actually get back to nature these days, which means it’s becoming harder to locate an authentic natural experience for our children, all while recognizing the additional contradiction that the only path most of us can use to seek out such an experience is to pile the family into an SUV or a van and drive in our environmentally unsound vehicles to find a place where the environment has largely been tamed for our consumption. An additional layer of irony lies in the fact that when we camped back then (as well as when we camp today), we as often as not used the car itself as part of our camping equipment, tying ropes to it for the tent and/or an awning, dropping the back gate on the station wagon as an extra table, opening the door and playing the radio for entertainment. When our family camped at Gull Lake, the station wagon was almost as much a part of our camping experience as the beast tent.

It all raises the question, in retrospect as much as in the present, of what precisely it is we’re achieving when we “camp,” particularly in the highly organized sites described above, replete with water, showers, electricity, toilets, and check-ins with map distribution? Are we telling our children that this is nature? The only real difference between that type of camping and staying at home is a worse sleep and no cable TV. It might just be better to watch the Nature Channel on TV with the kids and a bowl of popcorn.

I jest. But only partly, because we do continue to cherish and demand our conveniences and gadgets, and this is, obviously and disturbingly, more the case with today’s children than with previous generations (not that they are to blame since it’s us, their parents, who are their prime facilitators in this regard). Still, the trend towards convenience in camping was established long before the Internet, long before the cellphone, before television even (for many of my younger readers, this period—Before Television—is what your teachers mean when they talk about “pre-history”). In the 1920s, Denver’s Overland Park was among the first campgrounds in the US to focus on a range of civilizing services; the Overland became the model for the KOA, which, to anyone who camped in the seventies, was as pervasive as tight jeans and bad haircuts. KOA was the Starbucks of campgrounds. This was part of its appeal to parents, my own included, who had enough to worry about without fretting over the unknown campgrounds they were taking themselves, and us, into. This would explain, I suppose, why we drove four thousand kilometres—one way—to stay in a KOA campground in Mexico City. KOA ruled the campground world at the time; it started with but a single campground in 1961 and by 1979 it had 829 campgrounds across North America. KOA had individual owner/operators, supposedly to put a personal touch on the service, though in our case, in Mexico City, it led to “personal touches” we could have done without.

The oil crisis may have been ongoing at the time, but I can safely say that none of us children were aware of it. It’s possible my parents took note of these world events, and it’s also possible they relayed them, but for that to have made an impact on us would have meant listening to them. Certainly I do not recall ever being unable to gas up during any of our stops, and once we hit Mexico City just before Christmas, you’d have been hard pressed to say the oil crisis was putting the squeeze on vehicle usage. Quite the opposite. We’d never seen traffic like it. Driving from the middle of Mexico City, from Chapultepec Park, say, to our KOA campground fifteen miles outside the city centre, seemed to take almost as long as it had to drive from Calgary to Mexico City. The snaking endless line of cars, six lanes regularly converging into three, the choking pollution caught in Mexico City’s unlucky inversion basin, the sheer number of people—we’d never seen anything on this scale. We’d also never camped outside a city of twelve million people. At times the KOA felt as crowded as walking through the city itself. Row after row of tents. It was a tented village, though this was hardly a negative thing. Some of the memories of playing in that campground are stronger than the time we actually spent in Mexico City.

That KOA campground no longer exists, or at least it’s no longer in the hands of the KOA. Whoever owns it now has, I’m sure, or I hope, relaxed the draconian laws of the place. They shut down things early. They closed bathrooms at ten o’clock at night. They shut off the water taps at 10:05. They turned off the electricity at 10:10. They closed the office and went home at 10:15. They locked the gate so no one could break in . . . but no one could get out, either. Basically, it was a jail without the humane conditions. Not that we especially noticed at first, as long as you weren’t thirsty or had to go to the bathroom late at night. They said it was a safety issue, which was fair enough, given that we were in a huge city in a third-world country and had gringo written all over our pasty faces. Only as our time there progressed did it start to feel oppressive. Still, we reasoned, we were nearly through with Mexico City, and from there it was off to the coast, to Acapulco, to see the cliff divers. Us boys were beside ourselves with excitement. Okay, Mexico City was one of the world’s great cities, a place with lampposts older than our country, the repository of an entire civilization. That was interesting, vaguely, but an hour away there were cliff divers!

Our last night in Mexico City was full of anticipation, for a variety of reasons, I think. One was the cliff divers. The other was the ocean and beachcombing, which we were all looking forward to after three weeks of driving through the desert. The sense of moment was also pitched because the day we left Mexico City meant it was the day we turned around. Even as kids I think we understood that we were on a very peculiar grand adventure and that as of the next day we’d be heading for home.

We wanted to make the most of our last night in the tent city and we played hard, exploring far and wide throughout the vast grounds. Late that night, before the water got shut off, Matt decided he was thirsty as we ran back to our tent. He put his lips to the nearest tap and took a drink, despite his brothers telling him not to. “You’re not supposed to, Matt,” we said. “You’ll get Mount Zooma’s revenge.”

We didn’t know the term, and had only heard our parents use it in relation to warnings not to drink water that hadn’t been boiled first. I can’t speak for my siblings, but I had no idea what the term referred to, other than that it meant bad things. Matt ignored us, we kept playing, and he didn’t seem the worse for it.

In the canvas cave at bedtime, my parents laid their own sleeping bags out in their room; the second, larger, room was held as the “living room”; the third room was where the kids slept. Our sleeping bags were laid out in a row, six of them, like coffins at a mass funeral. We crawled in as Dad shone the flashlight at us. He said good-night, and then said what he always said before he left us alone. “No horsing around. It’s time for bed.” We horsed around for a while and then fell asleep, but it wasn’t long before the inevitable came. Matt was in his sleeping bag between Bruce and Conor, and when Mount Zooma exploded, the eruption forever changed the lives of the people in that tent, of those who escaped and those who didn’t. Matt threw up as he woke up and instinctively turned to one side. It was fate, that was all. Conor or Bruce. One clean, one forever scarred. Who says life isn’t random?

Matt turned Bruce’s way.

Unluckily, Bruce tends to sleep on his back, face up. Well, he used to. I don’t know what position he sleeps in today. Or if he sleeps at all. And though Matt was at least a foot shorter than Bruce, somehow he’d managed to arrange himself such that their heads were side by side. A further piece of ill fate was that Bruce also tended to snore a bit, even as a young teenager, and consequently he usually had his mouth open.

Who knows what Bruce was dreaming about at that moment, but he was violently yanked from sleep. Everybody in the tent was up in a flash, listening to Bruce choke and swallow and cough, and to Matt moan. The rest of us were horrified, laughing at first, but then so truly sympathetic to the awful thing that had just happened to Bruce (and Matt was none too happy, either), that we didn’t laugh at Bruce or tease him or taunt him until well into the next day. We couldn’t really see much, either, because it was dark, after all, and we were camping in a tourist holding compound without any of the necessities for sustaining human life. Dad and Mom came scurrying into our room of the tent, with Dad jiggling his big flashlight. He trained it on Bruce and Matt, and we saw in stark relief what had just happened. Bruce looked like a wax figure left in a steam room.

The nature versus nurture debate has long raged in psychological circles, and I’m not here to come down on one side or the other, but you can’t tell me something like that doesn’t somehow shape a person. Bruce grew up to be a high school teacher, and to all outward appearances seems a normal and balanced person, but, let’s face it, the jury’s still out, and if he dropped off the edge tomorrow into a life of crime and addiction, I know what I’m blaming.

My mother sprang into action, immediately trotting out her greatest gift, her empathy. She tried to make Bruce feel better and attended to Matt.

“Gerry,” she said to my father. “Look at this. Oh my God. Poor things. Go get some water so we can at least clean Bruce off, and they can all get back to sleep.”

My dad stood there, looked at his watch.

My mom looked back to him. “What?”

“It’s two in the morning.”

“So . . .”

“No water. It’s shut off.”

“But don’t we have any?”

My father shook his head. “I was going to boil some more in the morning before we left for Acapulco.”

The full horror of it hit us all, but none more than Bruce. “You mean I can’t even wash off ?!”

“Oh, that’s just so gross,” emphasized Janine. “I think I’m going to be sick.”

My mother helped Bruce clean off as best he could. It wasn’t until the morning, though, until the full light of day arrived, that we were able to see just what Bruce had endured. His face was a strange hue, almost orangey-peach, like he’d used too much fake-tan cream. His hair was stiff and coarse, pre-punk, sticking out in forty different directions. Nobody used hair gel back then, but, again in reference to the nature versus nurture debate, I don’t think it’s any coincidence that Bruce today is the one amongst the six of us kids who pays the most attention to his hair and overall physical appearance. He has, for a male high school teacher, an unusually keen interest in hair products and facial cleansers.

We left Mexico City later that morning, after Bruce had cleaned up and Matt had thrown up another couple of times (into a plastic bag; nobody would go within five feet of him). We were turning for home, but first we had most of North America to travel back through, only this time we were headed up the length of the west coast, to Acapulco, Mazatlán, Puerto Vallarta, San Diego, and Los Angeles, before turning back inland to go through Vegas and back up the eastern edge of the Rockies, through Montana, and finally back to Alberta. A few days later, after a visit to Acapulco to see the cliff divers (which turned out to be a colossal disappointment as the various Mexicans present refused to dive off the cliffs for us, and because our mom wouldn’t let us out of arm’s length when we wanted to look for divers), we continued back north. We decided to stop in Guadalajara, for a much-needed rest. My parents decided to open their wallets for a motel. It was almost New Year’s, and I think they thought beds and a swimming pool would help take the edge off the collective trauma of Mount Zooma. They were right . . . for the most part.

KOA, incidentally, was sold in 2001 to Interactive Corp., which also manages Ticketmaster, Expedia, and hotels.com, a fact that makes it even clearer that camping is now a radically different thing than in generations past. It’s one piece of recreation for the masses, one writer noted, which can “be bundled along with other forms of entertainment.” Online planning and preparation for camping has become the norm. The government of Alberta recently introduced a provincewide campsite reservation system that has proven enormously popular; a necessity, in fact, for securing a campsite during busy times.

Yet this, along with all the other mod cons mentioned earlier, is not camping in the way that I understand it, or want to understand it. I speak not as an experienced naturalist, but as a modern urbanite who nevertheless longs for the (admittedly occasional) genuine immersion into nature’s unfettered beauty, an immersion unpolluted by humanity’s presence, except for my own, of course. I fear my children will lose access to those places, and moreover, that they will lose access to understanding how fragile our lives are, and are meant to be, in the natural cycle. Perhaps camping, as I think of it, is not even about nature at all (at least not “nature” in the way that we commonly understand it—as something to appreciate and revel in). Perhaps it’s about trial and difficulty and resistance. Camping isn’t supposed to be easy. It’s not meant to be frictionless. Isn’t that, at some level, what we’re trying to achieve when we want to take the kids camping? I know it’s the case that when we camp, one of the objectives is to remove Jess and Grace from the convenience and fluidity of their daily lives, to the point where we need to get that fire started or we don’t eat. The removal of physical obstacles is, I would say, counter to the point of camping as a family. You want to make it hard. Some of my best camping memories involve when it was hard, such as when Cathy and I camped in northern Alberta and forgot our axe. We made fires the old native way, just laying logs in a firepit like spokes on a wheel, pushing them in as they burned. There was no other solution. Of course, this was also the camping trip in which Cathy swore that fish were attracted to mini-marshmallows, which led to a few dozen coloured blobs floating into shore as every fish in the lake assiduously turned up their gills at the little morsels.

I suppose in the end camping as a family vacation, or even as a short family activity over a weekend, is for me more about creating a set of conditions than it is about communing with nature, though I have nothing against communing with nature and will always happily accept it as a secondary benefit. After all, a thirty-foot fir tree in my backyard is more or less the same as a thirty-foot fir tree in the forests of Alberta’s wild and unpopulated eastern slopes. There is something appealing, however, about leaving the city and leaving all those people behind, but is it possible that in so doing we are in fact trying to teach our children a different lesson: that not everything gets handed to you on a silver platter . . . and that sometimes what gets handed to you is something you’re going to have to eat off a tin plate crusted over with last night’s baked beans. And that WiFi, hot showers, and central heating are wonders of modern convenience and fortunate birth circumstances, not inalienable human rights.

My friend, the poet Tim Bowling, says one of the things he most cherishes about living in Edmonton, with its harsh winters, is that he likes to be reminded every now and then that nature has the power to kill you if you make the wrong decision. That, it strikes me, is about as good a lesson as you could hope to give your family by going camping. What could be more fun than that?

*