Читать книгу Farewell Shiraz - Cyrus Kadivar - Страница 18

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление7

Age of Innocence

Our first house in Shiraz was a modern two-story building flanked by identical white houses in Behbahani Street, in a quiet and friendly neighborhood. Behind the purple steel gate leading from the street was a paved courtyard where my father parked his car every night after a long day at work. When my grandparents returned to Tehran it was Uncle Farjoud, Mamie Kouchik’s brother, who dealt with getting our telephone, refrigerator, radio, and television antenna installed. Father asked a Zoroastrian carpenter to make our sofas, chairs, beds, tables, wardrobes, and bookshelves. My mother found the kitchen dark and the bathrooms too small but was otherwise pleased with her new Iranian home.

During the months that followed, the rooms were painted in soft colors and decorated with blinds, thick curtains, mirrors, local paintings, and red woven carpets. On the ground floor was a long corridor that separated the bedrooms and led to a square living area where we gathered for family lunches and dinners. Upstairs was another square area that was used for watching television, two guest rooms, and an L-shaped living and dining room with a balcony in the front. The top floor had a glass house, where my mother kept some of her plants; a storage space; and an extra guest room that opened onto the flat, expansive roof.

From the start my mother was disappointed by the lack of a real garden, and there was a depressing look about the stone pool with its broken fountain. Winter was mild, and in the spring my mother planted violets, petunias, and daisies outside her bedroom window in stone boxes that ran along the veranda. She was delighted when my father hired a gardener, Baba Soghra, a Qashqai who had left the hinterlands and moved to Shiraz. He was a quiet and lean man, who always looked neat in his white shirt and dark trousers. Baba Soghra immediately sensed what my mother wanted and planted more rosebushes. He brought a dozen terra-cotta pots filled with geraniums and placed them along the walls and steps to the patio. Several times a week, when the sun had gone down, Baba Soghra would cycle to our house and water the small patch of lawn, the banana palm, and the sprouting flowers. In the afternoons he would hose down the dusty courtyard to wash away the dust and freshen the air.

His wife Maryam and their daughter Soghra took care of the daily household chores, which included beating and washing the carpets and leaving them to dry. Soghra was a sweet girl, no more than twelve years old. She had an intelligent face and long, braided black hair that reached her hips. When not in a gray school uniform she wore her pink tribal dress and gold bracelets. In the evenings when my parents were out, Soghra would hold me in her arms, listening to folk music on the radio. She liked telling me stories about her tribe and the hardships they suffered during the perennial migrations. She was always doing her homework and dreamed of becoming a nurse. I loved the Qashqais.

Not long after our arrival my father’s cousin Iraj Mehrzad, a major landowner and MP for Shiraz, invited our family to the village of Kaftarak where, with the help of his friend Bahmanbeigi, he had built a school and bathhouse for the Qashqais living there. We even watched a tribal wedding, with at least fifty horsemen firing their old rifles and a group of dancing girls in colorful skirts cheering the bride and groom. That day Mehrzad gave a khan’s feast for his guests under a black tent with the sound of drums and trumpets playing late into the night.

In the summer our family slept on the roof. Usually in the morning I found the beds next to me empty, the pillows and covers rolled up in a ball. My parents were up early with Mother feeding my baby brother. I was always the last one to move, usually awakening to faint birdsong. I knew it was time to get up when the sun began caressing my feet, which stuck out awkwardly from under the light quilt. With my eyes half-open, and lying in bed, I marveled at the flawless blue sky as a new day beckoned. Throwing aside the covers, I would slowly put on my clothes. With the shade gone, the ground was too hot to walk barefoot. Finding my sandals, I would move toward the edge of the roof. In the blinding light I could barely look at the city: a sea of white, brown, and green. From my vantage point the houses with their flat roofs appeared small, each a self-contained world. The narrow alleyways we called kuchehs were alive with people.

Occasionally a zooming motorcycle, a braying donkey, a honking car, a barking dog, or even a quarrelsome neighbor would shatter the illusory tranquillity. Twice a week, an old man on a little white donkey appeared at our door selling grapes, peaches, apples, and watermelons. There was a postman who brought us stamps, letters, and magazines. Sometimes the neighborhood kids playing in the streets would kick a ball over our walls and ring the buzzer asking for it back. One could never tell who would be next. I will never forget the barefoot Gypsy girl who managed to slip past the gate, singing and dancing wildly in the courtyard until my exasperated mother paid her to leave.

Another time a grateful villager brought us a black sheep to thank my father for saving his son’s life. We let the animal roam in the garden until Baba Soghra arrived one day with a butcher’s knife. Before my mother realized what was happening Baba Soghra took the poor creature into the backyard and cut its throat. Mother was near-hysterical with shock at the sight of all the gushing blood.

Fortunately, my mother treated these events as a learning experience. It did not take her long to get used to her new life. She never forgot the kind welcome by Elma, an Armenian lady, who brought her flowers and lived opposite us.We were on good terms with our next-door Iranian neighbors, but never too close. On one side was a Tehrani hairdresser married to a cantankerous army colonel. Their daughter, curious to meet me, was forever popping her head over the wall looking for her ginger cat. On the other side lived a wealthy merchant from Yazd and his young, pretty wife. She was always alone and bored since her husband had to go on long trips.

With my father away at the hospital my mother was glad to have Roghayeh by her side. Roghayeh was always up at the crack of dawn saying her prayers, changing the sheets, and making breakfast. Roghayeh was a sturdy woman in her late twenties, modern and religious. She had been adopted as a young child with her brother by my grandparents after their parents died from typhus. Roghayeh had been raised like a daughter by Mamie Kouchik, and my father, who had known her as a child, treated her like a sister.

Unmarried, she was full of energy and blessed with a kind heart and sunny personality. She was determined to show us the old parts of Shiraz and often acted as our guide through the spice market and winding Vakil Bazaar, where we drank tea with the merchants and viewed their carpets. Another time I went along with my mother and Roghayeh to a ladies’ hammam. The experience shocked me. The terror of standing among a cluster of stark-naked women, chatting, bathing, and scrubbing themselves, was made worse when a large-bosomed woman tried to pull off my shorts to wash me.

Then there was the time when Roghayeh tried to smuggle my mother into the Shah Cheraq Mosque, one of the holiest sites in the world of Shi‘i Islam in Iran, after those in Mashhad and Qom. The guardian, a pious Muslim, had not been fooled by the foreigner’s chador. While the man protested that it was Friday and the historic mosque was closed to tourists, I slipped inside, only to get totally lost in the vast hall with its ornate tiles and intricate glassworks. Wandering through the mosque I found myself among a dense crowd of faithful worshipers. All around me were men kneeling and praying. I was about to run when a hand seized me, pulling me down. A grizzly old man stared at me. As the sound of prayer filled the hall I began to run down the rows of carpets. By chance Roghayeh spotted me near the golden mausoleum. She grabbed me and hid me under her sweaty chador and, after throwing some money at the tomb of Mir Seyyed Ahmed, the son of Imam Musa, returned me to my worried mother.

One night while sleeping on the roof with Roghayeh, we heard our Yazdi neighbors shouting: “Thief! Thief!” Startled, Roghayeh and I ran toward the balcony railings and saw two men climbing over the walls with a television set over their shoulders. Within minutes all the neighborhood lights had come on. Everybody seemed to be looking for the thieves, who had vanished into the night.

A week later, as we were having dinner on the veranda, we heard a great commotion beyond the walls. Outside, a large crowd had surrounded a young man. Father asked who he was. “This is the thief!” a woman shouted. A drunken policeman was summoned from a nearby nightclub to question the man, who confessed to being behind a spate of burglaries in our area. His accomplice was never found. Finally, a police car arrived and the man was handcuffed and taken away to Zand Prison.

On the whole, though, Shiraz was a safe town in those days. Our city had a certain appeal with its broad tree-lined avenues, drab buildings, parks, and a cheerful population that did not exceed a quarter of a million people. Over time my mother found the confidence to leave the house on her own to do the daily shopping. She soon made friends with the local policeman, baker, and shopkeepers on Rudaki Street. On the main Zand Boulevard was a grocery store run by a cheerful Armenian, Michel, and his assistant Albert. At Michel’s my mother purchased her filet de boeuf, peanut butter, hamburgers, chips, pickles, ketchup, and beer. I used to accompany her with my father, hoping to see the fluffy white puppy that sat outside the entrance. Michel always gave me a handful of pistachios.

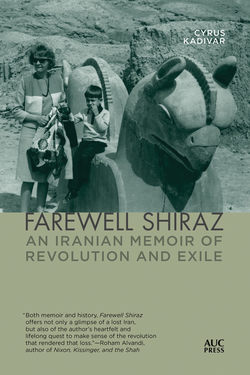

One day at Michel’s my mother met Lizette, an elegant Swiss lady from Geneva, married to Habib Farpour, an Iranian eye surgeon. My mother and Lizette became good friends. Together they used to take turns gathering some ladies, mostly French and married to Iranians, at their homes. Over coffee they gossiped and exchanged stories about the challenges of living in Iran. Despite the headaches of coping with their busy husbands and growing kids, demanding relatives and servants, they had picked up enough Farsi to get by and had largely adjusted to Persian customs. These women enjoyed contented lives, like many other westerners living in Shiraz, and had their own schools, clubs, and activities. They organized picnics and excursions, gave parties, and went to the movies. I also recall a family outing one gorgeous spring day to Cyrus’s tomb at Pasargadae, an empty yet haunting monument to the greatest king of antiquity. Then there was Persepolis or Takht-e Jamshid. Just an hour away, northeast of Shiraz in the Marv-Dasht plain, it left me utterly astounded. From an early age I felt a connection to Iran’s royal past. Exploring the fallen stones, my hands traced the sunbaked limestone bas-reliefs that depicted the immortal guards, ferocious lions, winged human bulls, satraps, and vassals bearing gifts for the King of Kings. For a little boy who loved to pretend to be riding a golden chariot, Persepolis was the ultimate fantasy playground. I still have a picture of myself, barely five, sitting on a stone griffin with my mother posing beside me with sunglasses. The summer months came and went until autumn arrived. Mother was expecting her third child and everyone was excited.

That autumn, as the country prepared for the shah’s long-awaited coronation ceremony, my mother gave birth to a baby girl at the Nemazi Hospital on October 5, 1967. Father was so proud of his Shirazi daughter. My parents called her Roya, meaning ‘dream’ in Persian, but also added Sylvie to her name. Every morning I would join my brother as we peered into my sister’s cradle, tickling her. We couldn’t wait until she was old enough to play with us.

When I turned five my parents put me in an Iranian kindergarten called Moadel. Not only was I torn away from my cozy and secure home environment, but I had to wear a uniform and have my hair cut short. I felt miserable and lonely, an alien among my classmates. There was another boy with a cheeky smile and freckles who felt the same. His name was Karim. He was the son of an Iranian industrialist and an English mother. We became instant friends.

Once, as we sat in class together, our teacher asked everybody to leave the classroom and assemble in the yard. Reluctantly Karim and I stood shivering beside twenty other boys dressed in pristine white uniforms. That morning the headmistress welcomed Queen Farah with a curtsy and a simple handshake. There was a lot of clapping and cheering as the shah’s wife made her way toward us. She exuded a quiet charm in her wide-brimmed hat and long dress. As her royal aides, bodyguards, and the school staff looked on, each pupil stepped forward and offered her a rose. When my turn came I froze in my place.

The headmistress, an intimidating lady, turned red with embarrassment and in a theatrical whisper hissed, “The rose . . . the rose,” while making urgent hand gestures. I started to cry. Queen Farah looked at me with her large brown eyes, took the rose, and then, wiping my tears, kissed me tenderly on the cheek. A souvenir photograph of the royal visit was sent to me a week later, which made my parents proud. But the memory of that special day stayed with me forever. A fortnight later I saw our queen again, this time on our black-and-white television, as she stood beside the shah and her eldest son in full regalia at the Golestan Palace.