Читать книгу Farewell Shiraz - Cyrus Kadivar - Страница 19

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление8

Spellbound

On October 26, 1967 a wave of inordinate excitement swept over our household as we sat in front of the television set in our living room, viewing the spectacle held at the Golestan Palace. Although our king had ascended to the Peacock Throne over a quarter of a century earlier, he had delayed his formal coronation until his enlightened reforms had put our ancient nation and the Pahlavi dynasty on a sound economic and social footing. Now on his forty-eighth birthday, confident of the future, Mohammad Reza Shah stood proudly in full imperial regalia, his jewel-encrusted golden sword at his side. Moments earlier an elderly courtier had placed a pearl-embroidered cashmere mantle on the shah’s shoulders.

The Friday imam presented the Quran, which the monarch kissed reverently. Then with great solemnity, the shah, imitating his late father Reza Shah, raised the scarlet-feathered Pahlavi crown studded with precious stones above his head and crowned himself as a chorus sang the hymn to glory. Later, the shah placed a specially designed crown on the head of his kneeling wife, twenty years his junior. When he helped Farah Pahlavi to her feet, everybody knew that she had become the shahbanu, or empress of Iran. Seated on a gem-studded throne, the emperor was handed the royal scepter by Court Minister Alam.

In a moving speech the shah stressed his unshakable bond with the Iranian people and vowed to do everything in his power to improve their lives and make Iran a greater country. But the real star that day was seven-year-old Crown Prince Reza. My parents were very impressed by the way the little prince in his blue uniform carried himself in the aftermath of the ceremony. The boy walked in a dignified manner down the long red carpet, flanked by officers. A cast of five hundred generals, ministers, diplomats, journalists, and ladies in long satin robes bowed and curtsied. The crown prince joined his smiling parents in a golden carriage pulled by six white horses through the streets of Tehran, applauded by crowds lining the route leading to the Saadabad Palace. A month later, when my grandfather Mohammad Kadivar came to see us, he gave me a book full of stamps of the imperial coronation. As a child, I felt a bond with the young prince who was marked to be the next shah one day.

My grandfather, like many loyal Iranians, accepted the king as the only constant of political life, but during his stay with us, he told my parents that the shah’s decision eight months earlier to ban all public rites of mourning for the late Dr. Mossadegh, who had died of stomach cancer at the age of eighty-five, had upset people. The great patriot who had nationalized Iran’s oil industry had been quietly buried on his estate in Ahmadabad, where he had spent most of the remainder of his life following three years in prison for treason against the crown. On the other hand, Papi Kouchik was happy to see that the Majles had passed the Family Protection Bill. Under its provisions, a woman could sue her husband and win custody of her children in a dissolved marriage. The Shi‘i practice of temporary marriage was abolished and the legal age of marriage was raised from nine to fifteen. “The old ways must give way to the new,” he said, smiling.

In the spring of 1968 we drove to the capital to see my grandparents. Arriving in Tehran after a two-day journey via Isfahan, we were covered in dust. Everybody fussed over my sister and brother, leaving me to my own devices. I was constantly exploring the big house with Golzar’s children. There was a top-floor room where Mamie Kouchik kept my father’s childhood clothes, books, toys, and hunting rifle. My parents took the opportunity to see the crown jewels in the vaults of the Melli Bank and visited the Royal Tehran Hilton. Awaiting the Persian New Year, the family gathered in the salon, dressed in our new clothes and eating nuts and sweets. We sat around the Haft-sin table with its seven items: painted eggs, coins, a mirror, green shoots, a copy of the Quran, Hafez’s Divan, and a hyacinth.

I stared at the goldfish in the bowl while Papi Kouchik kept an eye on his watch until the radio announced the arrival of Nowruz. We exchanged gifts, received a gold sovereign each from my grandmother, and listened to the shah’s radio address wishing the nation a prosperous and peaceful year before enjoying our sabzi-polo mahi dish. In the afternoon, I saw my grandfather snoozing in his armchair, his heavy eyelids firmly shut. He seemed at peace. I studied his wrinkled face, the square-shaped mustache, his carefully combed thick black hair tinged with gray. Suddenly he opened his dark, deep-set eyes and, laughing heartily, gave me a big hug. Later he showed me his book-lined study and two white doves nesting in a gap under the roof.

The next day, however, my grandfather complained of chest pains. Father took his blood pressure and, finding nothing abnormal, gave him some pills. Mamie Kouchik observed him anxiously and my father filmed her placing a rose in her husband’s lapel with tender affection. He seemed better in the evening when his guests arrived. That night, as the adults were busy entertaining their friends and relatives in the courtyard, my grandfather called me over. Stroking my head, he gave me a ripe apricot. After I had eaten the juicy fruit he told me that once I returned to Shiraz I was to dig a big hole and plant the stone near the pool. “Make sure to give it plenty of water,” he said. “One day this stone will turn into a big tree.” He gazed at me affectionately. “When the tree bears fruit, think of me always,” he whispered. Five months later, while I sat on my bed listening to my mother reading passages from Le Petit Prince by Antoine de Saint-Exupéry, the telephone rang. It was my grandmother.

Calling from Tehran, Mamie Kouchik was in tears as she tried to explain what had happened. That morning, August 19, 1968, my grandfather had gone to the park to watch the annual parade marking the uprising that had toppled Mossadegh and installed the shah on the throne. Feeling the intense heat, Papi Kouchik came back home around ten o’clock. Sitting on his chair under the trees, he peeled a small cucumber—one of his favorite snacks—that Golzar had brought him. He had hardly taken one bite when he had a heart attack, collapsed, and died. Mother wept as she told me the news and we cried for a very long time. Father was devastated and flew to Tehran to comfort his grieving mother.

In accordance with Islamic custom, my grandfather’s body was ritually washed and wrapped in a white shroud. At the funeral a mullah offered prayers for the soul of Mohammad Kadivar, who was later buried at the Behesht-e Zahra. We all felt his loss. One day I went outside to our little garden and, using a twig, I dug a hole and planted my apricot stone in the ground next to the pool. By the following spring the apricot tree had blossomed. Eventually it grew taller than the walls. Each time I picked one of the juicy fruits, I fondly recalled my beloved grandfather.

After the sad times following Papi Kouchik’s death, I was ready for my first year at the famous Shiraz International Community School (SICS). Founded a decade earlier by a group of foreign women married to Iranians, the curriculum ran along American lines. I could hardly contain my excitement when my father took my hand and introduced me to my tall teacher, Mrs. Thompson. Any fears I had soon evaporated. Seated next to me was my friend Karim. He was happy to see me. Unlike Moadel, where we had struggled with our limited Farsi to memorize Persian nursery rhymes, our new school was more liberal. Classes were taught in English. Most of my classmates were the sons and daughters of prominent families and expats living and working in Shiraz. There was no school uniform and so we all wore whatever we wanted. Our school was a sandstone building with lively painted rooms converted into classrooms. Between studying and lunch we were allowed short breaks for our daily gym session. As I grew older my parents allowed me to walk the short distance to school alone with a packed sandwich in my lunchbox.

A year after Papi Kouchik’s passing, my father engaged a private tutor to help me improve my Farsi. Although I could understand and speak the language, my reading and writing were poor. I had a lot of catching up to do. During the summer holidays Mr. Mohammad Kojouri would arrive in the morning with a stack of books under his arm and spend two hours helping me build up my language skills. The exercise books meant nothing to a boy used to the English alphabet. The strange Persian scribbles on the pages resembled codes in need of deciphering. Next to each word was a picture. On occasion Mother joined me in the lessons held three times a week and together we picked up some useful phrases.

To be honest, I dreaded these sessions and was bored to tears. Mr. Kojouri was a strict teacher and very disciplined. I used to count the minutes before our break, when I gazed at the bumblebees and butterflies hovering over the stone flower boxes on the patio. To break the monotony Mother brought tea, biscuits, and sweet, juicy watermelon slices. These blissful moments lasted fifteen minutes before we resumed our lessons. Once my tutor had left, Mother would grab some towels, put them in a bag, and take her children to the Nemazi Hospital by taxi. Hidden in the lush grounds, behind the pines and gardens and the dozen white stucco villas occupied by Iranian and foreign doctors and their families, was a large Olympic-size pool.

At the pool in Nemazi we kids learned to splash around and dive. Lizette and her two children, Bijan and Sandra, were often at the pool, and so were several of my classmates. Father would arrive at noon for a swim and we’d lunch on sandwiches, cheese puffs, and Pepsi-Cola. When the sun had disappeared we returned home in my father’s car, stopping along the way to buy baguettes at Katya, the only European bakery in town, run by a Belgian lady. Other days we went to the British Council with its majestic garden, movie house, and well-stocked library. That July of 1969, while the world was spellbound by the Apollo 11 mission to the moon, the shah, with the support of U.S. President Nixon, was preparing to become the policeman of the Persian Gulf as the British withdrew. It was the time of the war in Vietnam, Soviet machinations, and the Arab–Israeli conflict. By contrast, Iran, thanks to our king’s leadership, stood out as a haven of stability and initiative. We seemed to be entering a “Golden Age.”

There was no doubt that the shah was enjoying great popularity among the masses. His nationalist rhetoric continued to attract genuine support. The country had two official parties: the Mardom and the Iran Novin. There were lively political debates and local elections. Communists, Mossadeghists, and Khomeinists were barred from participating. Prime Minister Hoveyda cleverly turned the shah’s whims into state policy. His government promoted education, women’s rights, and social and economic development on a large scale. Literacy and Health Corps brought schools and hygiene to the most remote corners of the land. Oil revenues were poured into infrastructure projects. New universities were built. The police and the armed forces were modernized and expanded. Living standards grew dramatically, as did the professional middle class.

These things were always in the background and I think my father, like most Iranians at the time, accepted the fact that so long as the shah lived, his authority appeared to guarantee political stability. One had only to look at the map to realize that our country was surrounded by authoritarian and dictatorial regimes far more brutal than the royal system governing Iran. For me, an eight-year-old boy, all that mattered was my family and the excitement of life in all its splendor. From my window I watched the parade of seasons with my brother and sister. After summer and autumn came the rains, followed by snowflakes in time for Christmas, which Mother celebrated as she had done all her life. Winters were mild in Shiraz. Over the spring holidays my father would bundle the family into his car—a pale green, second-hand Opel he had bought from Elma’s husband—and drive out of town. He loved speeding through the desert and listening to Iranian music on the car radio. We visited ruins, waving at camels and Qashqai nomads in the hinterlands.

One time I stood on a Sasanid bridge in Dasht-e Arjan and went fishing near Pole-Fasa with my father and his friends and slept in a tent. Another time we joined a Belgian couple and their freckled ten-year old daughter Hilda on an excursion to Lake Parishan, where we surveyed the wild ducks and exotic birds at sunset. The next day, after staying the night in a Kazerun caravanserai, we drove through dangerous mountain passes to the port city of Bushehr and spent an unforgettable time along the shores of the Persian Gulf.

My parents were also very sociable, always hosting or being invited to parties. I loved watching my parents dress up for the evening and always helped my mother put on her pearl necklace. The French consul, Monsieur Delion, and his wife gave regular cocktail parties that my parents attended. There were elegant soirées held at the homes of other Shirazi doctors, where newcomers and foreign visitors also mingled. On Thursdays we often lunched at Uncle Farjoud’s house near the Khalilli Botanical Gardens. His wife, Akhtar Khanoum, and her three beautiful daughters, Vida, Jella, and Mitra, were always generous with our family and delighted to see us. Our house was always open to visitors, who often arrived impromptu, sending my mother into a panic to fix a drink or cook up a meal.

Mother was unwell that summer of 1970. She had been suffering from chronic back problems for some time. She had to take painkillers and sleep on a hard mattress. The day she had to have her back operation, Elma, our caring Armenian neighbor, took me, my brother, and my sister to the cinema to see The Sound of Music. In November 1970, while Mother recuperated from surgery, my French grandmother arrived from Paris to give her bedridden daughter a helping hand. Having two grandmothers in the house was not without its complications. They spoke separate languages and each practiced her own religion while vying for our love. I often watched cartoons sitting on a sofa between my grandmothers while they spoke together, with me translating their views on life. The greatest source of confusion for me during these exchanges was religion. My parents had never insisted on imposing Islam or Christianity on their three growing children. I grew up believing in God and respecting both faiths in order not to offend our competing but lovable grannies.

When Mamie Kouchik returned to Tehran with Roghayeh, my French grandmother took charge of bathing us, cooking our meals, and dressing us in the morning before sending us off to school. My siblings and I looked forward to coming home and tasting her delicious crêpes Suzette, ravioli, and piroshkies. Grandma Julia was a kind and stout woman with rosy cheeks, a devout Catholic, who never went to sleep before kneeling down by the bed to say a prayer. Although she had planned to stay with us for no more than three months, Grandma Julia remained in Shiraz for the next nine years. Her husband grudgingly accepted her decision, feeling that she would be happier with us, and was prepared to put up with their separation.

Thinking back to those quiet days when we were growing up in Shiraz, I now realize how little quality time my father spent with his three children. Father had a very hectic life working at the Nemazi and Saadi hospitals. He was also a professor at the Pahlavi Medical School. He often came home late. On weekends he would prepare slides for his lectures. Sometimes his American and Iranian colleagues would come to our house to go over their research papers together. Three years earlier, my father had been part of a team of Iranian surgeons that had successfully carried out the first groundbreaking live kidney transplant in Shiraz. His photograph had appeared in Kayhan newspaper alongside an interview with him in which he spoke proudly of his work. Court Minister Alam, the former Chancellor of Pahlavi University, had sent the shah’s congratulations to him and to the medical team.

Most nights I would wait for the sound of my father’s car and then run to open the gate. Father usually dined alone, as my mother had to spend long hours in bed until her back improved. Mother had been forced to give up teaching French to Iranian students at the Faculty of Letters after a quarrel with the dean a year earlier, when she refused to give the name of a student who had spoken out against the shah during his tour of the university. She rarely talked about this but I knew it upset her. In the evenings I used to sit with my father, talking to him as he ate his steak. If I behaved I was allowed to climb into my parents’ bed and watch the dubbed American series The Fugitive, Rawhide, Mission Impossible, and Peyton Place on a portable television set. On weekends, while mother brushed Sylvie’s hair, Darius and I would climb on my father’s shoulders or wrestle with him on the carpet.

We also had a decent family library. My brother and I used to spend hours going through the collection and looking at the pictures. Among the books there was one by Professor Arthur Upham Pope, the eminent American expert on Persian art. Pope, who had died two years earlier, and his wife, Phyllis Ackerman, had lived in Shiraz for a while and known my parents, who had nothing but praise for their work. One of Pope’s students, Richard N. Frye, had taken up his mantle and the shahbanu had given him an office at the old Qavam house known as the Narenjestan. One of Frye’s sons went to school with me, and several times I met his father, who encouraged me to read about Persepolis.

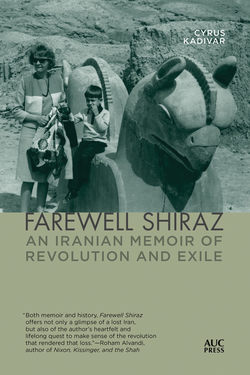

My fascination with these famous ruins had remained unchanged since my first visit as a young boy. My father must have taken us there a dozen times since we arrived in Shiraz. Archaeologists working there never failed to remind us how the Greeks had looted the treasures and set fire to the palaces on Alexander’s orders in revenge for the sacking of Athens by Xerxes. Centuries later, the remaining stone columns that sprang upward in the desert against the backdrop of purple mountains spoke of a forgotten empire long before Persia was invaded by the Greeks, Arabs, Mongols, Turks, and others. One time my father asked me and my six-year-old brother to run down the royal staircase while he filmed us with his beloved Super-8 movie camera.

I was approaching my ninth birthday when we revisited Persepolis. There were some big changes afoot. A new asphalted road now linked Shiraz to the famous ruins and hundreds of imported trees had been planted nearer the site. There was also a modern hotel nearby to house the journalists descending from around the world to cover the shah’s ambitious celebrations marking the 2,500th anniversary of the founding of the Persian Empire. In October 1971, a week before the event, a patient of my father’s, General Boghrat Jaffarian, offered to drive us in a military jeep through the magical Tent City erected by the French decorators Jansen to house the sixty-two kings, queens, sultans, emirs, and presidents attending the celebrations. It was a surreal experience. Everyone we met on the set that day was proud to be playing their part on the stage of history. Soldiers from the imperial army had been ordered to wear beards and dress up in costumes representing the major Iranian dynasties.

At the start of the program, Mohammad Reza Shah faced the tomb of King Cyrus at Pasargadae, where he saluted the great ruler in an emotional display, attempting to link his dynasty to the Achaemenids. The shahbanu and Crown Prince Reza shared this poignant moment of history with him. The elite Pahlavi officials did the same. But the main party really got off the ground at Persepolis. The VIP guests were amazed by the ostentatious banquets, parades, and imperial pomp. Like most Iranians unable to attend, we ended up watching the two-day extravaganza live on television. When it was all over we staged our own show at home. Wearing paper crowns, false beards, and long robes made by Grandma Julia, my brother and I marched in front of our parents in the guise of kings. Sylvie, my four-year-old sister, ran around the living room dressed as a Persian queen.

As we later discovered, the Persepolis celebrations were not without controversy, with reports of crates of expensive French wine and tins of Iranian caviar being siphoned off by crooked officials and sold on the black market. Some of our people mocked the shah’s “wasteful party” and his “divorce from reality.” Others felt proud. Here was an opportunity to tell the world that we Iranians belonged to a great and ancient civilization. Once the dust had settled, our city experienced a cultural revival not seen for a long time. European and American tourists flocked in vast numbers to Shiraz and the nearby ruins.