Читать книгу Strange Highways: Reading Science Fantasy, 1950-1967 - Damien Broderick - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

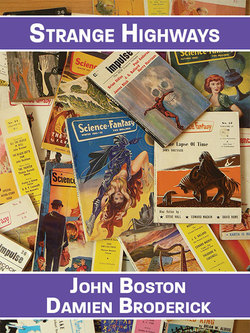

Оглавление3: SCIENCE FANTASY, VOLUME 3 (ISSUES 7-9)

Big news: the hyphen is gone from the magazine’s title. As promised, the format is now 7½ x 5½ inches, the page count is 128, the price 1/6. Also, the Assistant is Leslie Flood, though that line is gone in issue 8 and the only editorial name is Carnell’s. The colophon of 7 now bravely asserts “Published Quarterly.” On the other hand, the masthead merely says “1954,” no season indicated. But things are looking up. 8, 9, and 10 proclaim “Published Bi-Monthly” and have unobtrusive publication dates (5/54, 7/54, 9/54) hiding in the lower right corner. The covers of 7-9 are all by Quinn, agreeably composed and colorful but a bit crude in detail—though how much of this is the artist and how much the constraints in reproduction, I don’t know.16 Interior illustrations continue competently but without distinction from the usual suspects.

7 is fronted by Quinn’s portrayal of Martian ruins. This illustrates Francis G. Rayer’s lead novelette “Seek Earthmen No More,” a quietly nonsensical story in which the protagonist, a space buff, suddenly speaks out against Mars exploration, sways the audience and ruins his employer, who fires him. He decides to go to Mars himself to atone—not bothering to explain to anyone that his “let’s stay home” speech was actually telepathically dictated by an alien entity. And that’s not because he thinks no one will believe him. It just doesn’t seem to occur to him. Of course he gets to Mars and comes up with the completely uninteresting solution to the mystery; colonization will resume.

§

The lead novelette in 9, “This Precious Stone” by H. J. Murdoch (pseudonym of J. T. McIntosh), is of similar ilk to Rayer’s story. This one had been announced for publication in New Worlds, but was diverted to Science Fantasy after New Worlds’s long hiatus in publication. (See volume 2 of our companion survey of that magazine, Building New Worlds, chapter 4.) Martians and Earthfolk are fighting a war on Mars for water. The Earth types need water to fuel their spaceship, so they can go back to Earth and find out why nobody has showed up from there and brought them more water in quite a long time. A fighter pilot engages in a dogfight with Martian who turns out to be female, they nearly kill each other but manage to get to the citadel of the Healers, who offer a deal: we’ll save you if you go on a mission to destroy the propulsion unit of the Earth space ship. They take the deal (it beats dying), and plot mechanics work themselves out mechanically. The big revelation from the old and wise Healers is that sooner or later the spaceship propulsion unit will start a chain reaction that wipes out all life, and that is why no one has heard from Earth recently.

Both of these stories amount to denatured Planet Stories, going through the pulp adventure motions without conviction. In general that’s the problem with these early issues of Science Fantasy: there’s almost no fantasy, just mostly dilute, derivative, and/or poorly rationalized SF.

“Dilute” is not a word that fits the lead story in 8, E. C. Tubb’s “Tomorrow,” as over-the-top a piece of noir as has ever appeared in an SF magazine, or maybe anywhere. It’s after the Blowup, not described in any detail but seemingly a limited nuclear war (“He glowered at me [over the videophone], his flickering image streaked and marred with the trails of radioactive particles blown from the mainland, and I twitched with unconscious reflex action to the mind-disturbing radiation from the wind-blown debris.”). Destruction is uneven: there are a lot of ruins but there is still electricity (and videophones), and still diners (though sometimes staffed by mutants), and Carter’s building still has a doorman. Also there are still private detectives, of which Carter is one.

And here’s the theme: “This was a free world, had been since the Blowup, and a man did what he wanted, when he wanted, and how he wanted. That was freedom, and I was free.” The tone is set in the first three pages, in which Carter objects to his neighbor’s loud music and the neighbor takes exception when he complains (“The room behind him was full of smoke and stank of stale liquor and the heady scent of marijuana.”) What to do? “I shot him three times in the body.” Official reaction: the doorman says, “Next time do your killing outside the building, it saves a lot of work.”

Carter has an assignment: to track down some papers stolen from Atomic Power Inc., perhaps by agents of the dread “Antis” (anti-what is not much explained). With a brief pause to kill the three vengeful friends of the noisy guy he had already killed, and for appropriate medical care (“The surgeon clucked like an old woman as he saw my arm.”), he throws himself into his work, taking up en route with Lorna, the mottled-skinned mutant waitress from his local café, whom he takes on a date to the fights. (“The bout was between a middle-aged man and a lithe young girl. They fought naked with knives and the man was outclassed from the start...the girl slashed him to ribbons within five minutes... I glanced at Lorna from time to time, and when it seemed that she was about to vomit, I decided that it was time to go.”)

He receives the obligatory blow on the head about halfway through (“Then the pavement opened beneath me and I was falling, falling, falling. Falling into a black eternity.”) The story continues in this vein as we learn that everyone is double-dealing, and Lorna of course is dead by the end. The moral: “‘Yeah,’ I said, and didn’t recognize the sound of my own voice. ‘Freedom—it’s wonderful.’ Softly I kissed the dead lips.”

§

The short fiction in these three issues, overall, is a bit better than in the earlier ones, with fewer of the clumsy botches of the earlier issues—though also with little that is memorable. Those of greater interest include “Stranger from Space” by Gene Lees (7), about the emotional travails of a spaceman’s wife who has come to hate him because of his long absences. It’s quite well done up until the end, where it turns conventionally sentimental and O.Henry-esque. The blurb says “Miss Lees, a Canadian, captures the feminine angle in a manner no masculine author can hope to emulate.” Gene Lees did not appear again, but one Eugene Lees contributed an article, “Utopias—A Few Years Later,” to Science Fantasy 33 (February 1959). The blurb for that article acknowledges the earlier story by “Canadian journalist Gene Lees,” and adds: “Now working for an American newspaper, he has been on a European tour for his employer and is currently working from Paris” (emphasis supplied). Nothing is said about the earlier gender mis-assignment, so it’s unclear if Lees was engaged in a masquerade at the time or if Carnell simply assumed that anybody writing halfway competently about a woman’s emotional life had to be a woman. As Carnell revealed in his editorial in New Worlds 25, he learned the true state of affairs while attending a SF convention in Manchester, and met Lees, who had coincidentally checked into the room across the hall while stopping to visit a friend en route to a journalistic assignment.

Also interesting are a couple of pretty good stories by J(onathan) F. Burke (1922-2011), “Detective Story” in 7 and “Once Upon a Time” in 8. The former is a good-natured private eye spoof (“Jackson and I were on Mars at the time. We had been dealing with that grisly little business that was known on the telecasts for a week or two as The Case of the Corpse in the Canal. It was all tied up—the case itself, I mean: the corpse was too widely distributed ever to be thoroughly tied up, though we had done our wretched best.”) The latter is about a couple of kids from a benign and enlightened psi-powered future who get whisked into the paranoid and manipulative past (still our future) by somebody there trying to compose avant-garde music on his electronic instrument. It’s sort of at the intersection of “Mimsy were the Borogoves” (Lewis Padgett)17 and “The Skills of Xanadu” (Theodore Sturgeon), and very pleasant.

Brian Aldiss appears in 9 with “Criminal Record,” his first published story (not first sold) in the SF magazines, about some old record buffs who come upon a police recording about a criminal “smoof” accused inter alia of “timesliding,” and who make the mistake of placing an advertisement inviting the smoof to drop over. It is inconsequential but clever and well executed. Arthur Coster—who had two stories in the Nova magazines, and is the pseudonym of Richard deMille, who had four stories in assorted other magazines—contributes “Family Secret” (9), which in its way anticipates the Whitley Streiber school of alien abduction accounts, except it is the abductee’s wife who wields the rectal thermometer. Captain Semper, of the Air Force Flying Saucer Investigation, has bad dreams: he keeps waking up in the body of Omarpeff, who seems to be an alien crew member in Earth orbit (so the hints suggest) and is under interrogation for espionage, until his superiors finally believe him and sort of exorcise him. The story oscillates cleverly between the nightmarish and the domestic sitcom-ish. This, and Aldiss’s story, and the two Burke stories, display the kind of quirkiness and idiosyncratic voice for which Science Fantasy eventually became known.

What is surprising in these issues is how unimpressive are the stories by writers who had big reputations at the time. E. C. Tubb has one fairly trivial story, “Unfortunate Purchase” in 7 (a kid buys what he says is a heat ray at a junk shop, dad sees whatever it is needs fixing, and it is a heat ray—a story much like Aldiss’s except less lively), and one silly one, “Occupational Hazard” in 9 (spacemen commiserating in a bar about their wives being pregnant—space travel makes you sterile).

John Christopher’s “Death Sentence” in 7 starts as a sort of police-procedural about a space murder committed by the protagonist, but the real story is that in the absence of capital punishment, murderers are sent into the past, and he arrives just before the start of nuclear war. It’s well written enough, but gluing these pieces together doesn’t make them a story. A. Bertram Chandler’s “Six of One” (9) is a protracted pun story with a long windup and not much delivery.

And J. T. McIntosh’s “Beggars All” (7) is another story that convinces me that either McIntosh had a thought disorder, or I do. Space explorers arrive on a planet where colonists have been isolated for centuries living hand to mouth. They beg piteously for whatever technological boons might be available, incurring the Earth folks’ disdain. Meanwhile, there’s a beautiful female crew member (named Pretzel, for no discernible reason) for whom the ship’s commander has the hots, but he has suffered what he thinks is humiliating rejection. There is a revelation of why the colonists behave as they do which is then connected up with the romantic dilemma and its solution in a way that is as utterly uninteresting as it is strained and tenuous.

The remaining stories in these issues are mostly reshufflings of familiar material at various levels of competence. There is a pod of space epics. Lan Wright’s novelette “The Conquerors” (8) starts out in the territory of John W. Campbell’s “Forgetfulness” and Eric Frank Russell’s “Metamorphosite”: space explorers land on a planet of Sirius and find a road with a good-looking young woman sitting by it. She escorts them to her father’s house, where our boys learn that (handwaving) certain elements in the atmosphere destroy metal, so the natives have developed along very different lines from us. They teleport, don’t really have bodies but just make the humans think they do, and have already infiltrated Earth. But unlike the usual outcome in this subgenre, muscle wins out: one of the Earth humans reveals that their spacedrive, which is too big and heavy for their hosts to teleport, is decomposing fast, soon to blow up half the planet unless the aliens play ball with us. It is charmless but competently executed. The first of two stories by Margaret Lowe, “The Shimmering Tree” (8), takes place on a Venus mainly populated by poisonous plants. Exploring Earthfolk are disappearing, either not to return or to come back babbling about the “shimmering tree,” which turns out to be hypnotic and to enslave its catch. The protagonist gets away, but wonders if he really did get away as he awaits return to Earth. Smooth matter-of-fact writing mitigates the clichés, the protagonist’s rescue by his pet dinosaur aggravates them. Less well done is Peter Hawkins’ “Haven” (9), as clumsy and overlong as his earlier “Outsider,” about some Earthfolks who find an inhabited planet after their warship blows up; it will take a long time to get back to Earth and the war, and the question is which of the crew members will desert and go native and which will go back. The contrived ending spares the duty-bound captain from the choice.

“The Trojan Way” (7) by Francis Richardson (pseudonym of Lawrence Edward Bartle & Frank H. Parnell) is a smoothly written piece in which the characters flee Earth’s velvet-gloved totalitarian Welfare State (sic) for a distant planet, cleverly avoid detection and repatriation, and then come to a pointless bad end. Francis G. Rayer’s “Space Prize” (8) is another tiresome exploit of the canny space trader Mactavish. P. W. Cutler’s “Take a Letter” (8) is an epistolary story involving a supposed government agency sniffing out extraterrestrials and a supposed solid citizen who is helping them out; whatever shred of cleverness it displays is smothered by excessive length and archness of tone and gimmick.

There are two contenders for Prize Bummer in these issues. John Ashcroft, who had ten stories and a guest editorial in Carnell’s magazines and their nearest competitors, Nebula and Authentic Science Fiction, appears with his first story, “Dawn of Peace Eternal” in 8. This is an overwritten variant on “and then I woke up”—our hero is a captive of the terrible alien Thruna, but at the end we learn he’s really in a mental institution, and it’s just been mostly destroyed in a nuclear war. W. P. Cockcroft, a veteran of Wonder Stories, Tales of Wonder, and the 1939 fanzine version of New Worlds, contributes his last story, “Last Man on Mars” (9): an explosion kills everyone but the astronomer protagonist, who sits in his observatory drinking whiskey and listening to classical music and getting crazier with isolation, until a spaceship from Earth crashlands and the one surviving crewman lasts just long enough to tell him that war has started up on Earth again and that’s it for space travel and our hero’s prospects. It’s just as bleak as Ashcroft’s, but less noisy.

§

The Guest Editorials continue, and now they are beginning to display a bit more substance than before. John Wyndham is the Guest in 7 with “The Pattern of Science Fiction.” The blurb notes that Wyndham is “yet another member of the International Fantasy Award panel,” and I wonder if this is a talk he gave at an IFA function. He starts by mourning the low repute of the field and its name, though it’s hard to tell whether his complaint is more about perceptions of the field or the reality of large amounts of bad material. But some are keeping the faith. Which is?

Well, primarily, perhaps, that [stories] keep the rules... One of them is that a tale must proceed from its premise with adequate reason and logic... [I]n the imaginative story there must be a wholeness and a logic which is not cut across either by silly assumptions used simply to make a situation more exciting, or by silly inventions called up on the spur of the moment just to get the characters out of a jam. The unities of likelihood must be preserved to the best of the writer’s ability.

Now there is a nice line that articulates a point of SF aesthetics as succinctly as I’ve ever seen. Another nice passage, though debatable: “Then there is the science itself. It has to be there. It is the backbone. Backbones, however, are worn inside, not outside.” Returning to the former theme:

Invention, then, cannot afford to lunge out wildly. If it goes far beyond the known, or at least the suspected principles of its age, the reader no longer has common ground with the writer... There is plenty of this kind of thing where the author has got himself into such a state of utter confusion that he falls back on aggressively tough remarks of great stupidity leading to a series of pointless fights to keep things going, and, unfortunately, it is this kind of thing also that has now come to be commonly thought of as the pattern of science-fiction.

The object, then, of an annual Fantasy Award is to pick out the best exercises of controlled imagination—imagination working from data or theory within accepted limitations—work in which the writer has thought honestly, written carefully, and refused to abuse the logical implications of his theme.

Up next, in 8, is Wilson Tucker’s “Science into Fantasy,” which points out that yesterday’s apparent science in SF (about Mars and Venus, e.g.) is today’s fantasy, and so are some of the assumptions in contemporary SF, like the physical ease of space travel. (“The daily visit to the water closet is another ingenious booby-trap.”)

The Guest in 9 is J. T. McIntosh, whose “Something New Wanted...” is considerably more incisive than his stories of the time. “My experience of science fiction is that you, readers and editors of science fiction and fantasy magazines, are not really very keen on anything new, no matter what you say.” So how do we get new ideas? “...[S]omeone puts them in a story which does not go very far, but which is at least published somewhere. It comes in last or second-last in the magazine’s reader-rating, if any... Someone else sees the story and decides that it’s a good story gone wrong, and there’s no reason why it shouldn’t be used again the right way this time.” I.e., more conventionally. And so on. “You get what you deserve—but more than that, you get what you want. That’s why there are so few new ideas in science fiction.” McIntosh includes himself in this discussion, asking “is there anything new about these?” of a list that includes his One in Three Hundred. He does claim to have had a new idea once, but he won’t say what it is—he hasn’t been able to sell it, but still hopes to figure out how someday.

§

In other developments or non-developments, outside advertising continues at a low level. Most of the ads are house ads, which are growing: there are two-page spreads for Nova bookplates and big splashes for the Nova Science Fiction Novels, which fell flat despite big plans. (Five of them—including James Blish’s Jack of Eagles, Theodore Sturgeon’s The Dreaming Jewels, and A.E. van Vogt’s The Weapon Shops of Isher—made it into print.)

There is an ad in 7 for The Globe Tavern. It appears that proprietor Lew Mordecai, for whatever reason, left the White Horse for the Globe, so: “Habitués of the White Horse agree that sentiment goes deeper than panelled walls and, together with Mr. Mordecai,” have shifted the London Circle meetings to the Globe. A full page is devoted to this! Either that’s dedication, or the ad was free, or advertising space was really cheap in Science Fantasy. There’s also an ad for a “Fantasy Secretary”—apparently not a double entendre in that innocent age—who “will type, correct, and lay-out your Science Fiction story, technical article, etc., ready for you to submit to British and American professional markets.” And, most promisingly, half the back cover of 8 is an ad for the Royal Air Force Flying Review. New revenue frontier? No; this ad did not recur.

16. See these covers at http://www.sfcovers.net/mainnav.htm or http://www.philsp.com/mags/sciencefantasy.html.

1717. Pseudonym of Henry Kuttner and C.L. Moore.