Читать книгу Strange Highways: Reading Science Fantasy, 1950-1967 - Damien Broderick - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеINTRODUCTION, by Damien Broderick

Science fantasy is a blend, as you’d expect, of science fiction (the literature of drastic change precipitated by new phenomena and knowledge) and fantasy (the literature of unchecked imagination). So it tends to be bolder, more highly colored, than pure SF (as we’ll abbreviate “science fiction” or “speculative fiction”) but more disciplined than the exotic vapors or psychological uncanniness of pure fantasy.

As a commercial form, science fantasy got its clearest start with the American magazine Unknown, edited (rather surprisingly) by the classic nuts-and-bolts SF editor John W. Campbell, Jr., whose Astounding Science Fiction, later Analog, was the seed around which Golden Age SF crystallized in the late 1930s and early 1940s. Much of Unknown’s appeal lay in the imposition of the logic, or semblance of logic, of SF on the familiar matter of fantasy. Thus, in L. Sprague de Camp and Fletcher Pratt’s famous The Incomplete Enchanter (1941), the characters are translated into worlds of myth by capturing and internalizing their laws and assumptions—building a syllogismobile, as one character puts it.1 But while Campbell’s SF stormed toward a kind of hegemonic success in the new literatures of imagination, his Unknown (retitled Unknown Worlds for its last two years) never really caught on except among aficionados. It lasted from March 1939 to October 1943, and was killed by wartime paper rationing, which disrupted many magazines.

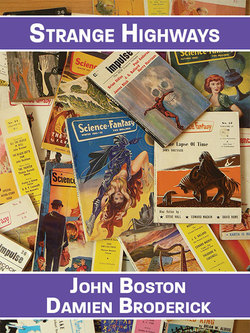

It can come as some surprise, then, that a parallel universe of science fantasy developed in Britain around the middle of last century, sometimes borrowing stories from the established US writers and magazines but also developing its own distinctive strains of fantasy narrative, most famously by new or accomplished writers such as Brian W. Aldiss, J. G. Ballard, John Brunner, Michael Moorcock and Thomas Burnett Swann. This book looks closely at the classic British science fiction magazine, Science Fantasy, that played a key role in this parallel-but-entwined history. From 1950 through mid-1964 it captured the sub-genre in its title, and often if not always in its contents, while for its last three years it appeared in rather different form, as Impulse and then SF Impulse, before shutting down in February, 1967 when its distributor was bankrupted.

The voice Science Fantasy aimed for, at its best, is caught well by Kenneth Bulmer and John Newman, writing as “Kenneth Johns” on the magazine’s tenth anniversary:

The added element of fantasy...gave a lightness and freshness, a whole new dimension to the contents that a magazine devoted solely to science fiction must, perforce, lack.... Certainly the magazine set out to bring before its readers material with that delicate touch of literary and imaginative magic, that slender but electric spark of wonder, that was rapidly dying out of much magazine science fiction.2

§

Two companion volumes to this one examine Science Fantasy’s fellow British magazines, New Worlds and the younger sibling of both, Science Fiction Adventures. As noted in the other books, Building New Worlds: The Carnell Era, Volume One, and New Worlds: Before the New Wave: The Carnell Era, Volume Two, John Boston is an occasional amateur science fiction critic of long standing, and attorney (Director of the Prisoners’ Rights Project of the New York City Legal Aid Society and co-author of the Prisoners’ Self-Help Litigation Manual).3 Several years ago, Boston read through every issue of Carnell’s New Worlds, Science Fantasy and Science Fiction Adventures—sometimes with grim disbelief, sometimes with unexpected pleasure, often with gusts of laughter, always with intent interest. All three magazines were edited during their important early years by Edward John (Ted, or John) Carnell (1912-1972). Ted Carnell was a pillar of the old-style UK SF establishment, but gamely supportive of innovators—most famously, of the brilliant J. G. Ballard, whose first work he nurtured.

John Boston, for his own amusement, found himself writing an extensive commentary on those early, foundational years of New Worlds, Science Fantasy, and Science Fiction Adventures. He posted his ongoing analysis in a long semi-critical series to a closed listserv devoted to enthusiasts of popular fiction magazines. The present extensive study, published in three parts due to the length of its exacting but entertaining coverage of these fifteen years of publication, is an edited and reorganized version of those electronic posts. This volume covers not only Carnell’s years with Science Fantasy, from the point at which it had become solidly established as a leading UK magazine of fantastika, but also its transformation and finally extinction under other hands.

I found Boston’s issue-by-issue forensic probing of this history enthralling and amusing, and read it sometimes with shudders and grimaces breaking through, and often with a delighted grin at a neatly turned bon mot. Don’t expect a dry, modishly theorized academic analysis. This is a candid and astute reader’s response to a magazine that, by today’s standards, was often not very good—but one that was important in its time. The story of how Science Fantasy got better, achieving and consolidating its position, is an essential piece of the history of the genres of the fantastic in the UK, and indeed the world.

I had the good fortune, as an SF theorist and writer, to read these chapters as they arrived via email. Greatly entertained, often flushed by nostalgia (for this was the literature of my remembered youth), I insisted to John Boston that his work deserved to be read by as many interested people as possible. He was busy on important legal work in defense of those lost in an overburdened US criminal justice (or “justice”) system, and had no time for such laborious scutwork. I rapped on his internet door from time to time, insisting that it would be a shame—a crime, even—not to allow this material to be read by the world at large.

At last he buckled, passed me his large files covering all the issues of Carnell’s New Worlds and the short-lived Science Fiction Adventures (some quarter million words), plus the current book’s worth of equivalent reading into Science Fantasy (my favorite as an adolescent, in colonial Australia). All three volumes of reading and commentary really comprise one large book of some 350,000 words. This third volume carries the saga through to the brief flowering of the New Wave in SF and fantasy both—a trend to which Science Fantasy stood in ambiguous and sometimes arm’s length relationship.

§

Science Fantasy’s forerunner New Worlds had a long and difficult gestation, and finally struggled into existence in 1946, although it managed only three issues before bankruptcy of its initial publisher, and only five more by the end of 1950 under the newly organized Nova Publications. It did not become a successful monthly until well into 1954, but in the meantime one of Nova’s founders, Walter Gillings, became the first editor of the new companion magazine, Science Fantasy, in 1950. Gillings had already launched his own magazine, Fantasy, which failed after only three issues and was followed by a semi-professional critical magazine, Fantasy Review (later Science-Fantasy Review). Gillings attempted to continue his earlier interests in commentary as well as fiction in the new magazine, but it was buffeted by post-war printing strikes and paper rationing, and by the third issue the board of Nova decided to oust Gillings and save costs by bringing in Ted Carnell as editor of both their magazines—to Gillings’ dismay and outrage.

Technical trade publisher Maclaren & Sons took over both magazines, later adding a reprint edition of the US Science Fiction Adventures, with the latter and Science Fantasy appearing bimonthly to New Worlds’ monthly. By 1963, all were in trouble—perhaps due to competition with cheap imported paperbacks from the US—and both New Worlds and Science Fantasy were rescued the following year by a somewhat disreputable publisher, Roberts & Vinter, Carnell departing to create his own quarterly series of original SF anthologies, New Writings in SF, with New Worlds’ editorship going to Michael Moorcock, although his notable work to that date had been the darkly brooding Elric fantasy stories published in Science Fantasy. Oxford art dealer Kyril Bonfiglioli (1928-1985) took on Science Fantasy, whose title he disliked and later changed to Impulse. When that title apparently confused the genre audience while failing to attract new readers of more refined tastes, it was switched, too late, to SF Impulse.

By general assessment, Bonfiglioli was a lazy and offhand helmsman, whose work was largely left to his assistants, James Parkhill-Rathbone and Keith Roberts (no relation to the magazine’s publishing house Roberts & Vinter), especially after Bonfiglioli famously bought a Tintoretto at a country auction for forty pounds and sold it for a thousand times (or perhaps 10,000 times) as much.4 Indeed, Roberts became, in effect, the editor, as well as providing some of the most remarkable fiction (especially the tales that would be compiled as Pavane) and many of the rather effective impressionistic covers.

For a brief moment it seemed that J. G. Ballard would become editor, and it is clear that he would have changed the magazine very drastically away from its science-fantasy roots—perhaps even more than Mike Moorcock was in the process of changing New Worlds into the battleship of the New Wave. In the event, Ballard was furious, and gone, when he learned that two issues (or at least the covers and tables of contents) had been put in process by Keith Roberts, and US writer Harry Harrison was brought in briefly to take the editor’s chair. As before, Roberts did most of the grunt work and more besides, and Harrison soon decamped to Europe. The publishers’ distributor went broke, and in February 1967, with its ninety-third issue under its third title, Science Fantasy was closed by Roberts & Vinter. It was a disheartening end to a magazine that in its various incarnations had provided a new kind of fiction not only to British readers but to the rest of the world as well, in the many stories drawn from its pages that appeared in US Year’s Best and other anthologies, or were listed as Honorable Mentions by the premier SF anthologist of the day, Judith Merril.

For some of us, Science Fantasy still sings a sirens’ song of magical memory, and its passing is a sting of frustration and rebuke. I am reminded of the opening of John Brunner’s long novella “Earth Is But a Star,” one of the great stories from the magazine:

“It’s a very small star,” said the man in gold doubtfully.

“Big enough,” said Creohan, and thought how tiny Earth was in comparison. The man in gold eyed him, and then gave another glance at the image in the field of the great telescope.

“This, then, is your device for seeing into the years to come?” he asked. “And is that all it will show?” [...]

“I have given you the chance to see into the future,” Creohan snapped. “Is it to be blamed on me that you have neither the wit nor the will to use that chance?”5

1. One of the magazine stories combined into The Incomplete Enchanter was titled “The Mathematics of Magic” (Unknown, August 1940).

2. Kenneth Johns, “The First Decade,” Science Fantasy, 43 (1960), p. 108.

3. See “The Long Road Toward Reform,” http://www.wahmee.com/pln_john_boston.pdf.

4. Different versions of this tale exist. Kevin Jackson, in The Independent, reports: “In 1964, Bon heard rumours that a Resurrection by a certain well-known 16th-century Venetian master was up for sale at an absurdly low reserve price. He went to the auction...and bought it, as if on an absent-minded whim, for 40 quid. It was, as he had immediately seen, a genuine Tintoretto. He immediately sold it for £4,000—a not inconsiderable sum...back in the Sixties” (19 July, 1999: http://www.independent.co.uk/arts-entertainment/celebrations-for-a-right-charlie-1107408.html) (visited 10/19/11). Brian Aldiss, who gets the painter wrong—he says it was “a Giorgione”—claims Bonfiglioli knew it was “worth a half million”: http://www.solaris-books.co.uk/aldiss/html/glass_forest_4.html.

5. Science Fantasy, 29 (1958), pp. 2-3.