Читать книгу Father's Day Creek - Dan Rodricks - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление– Father’s Day 2000, 6 am

I rose from bed, made some coffee, and drove from my in-laws’ house to the small parking area by the bridge over the creek. The drive to Father’s Day Creek takes you through farmland and forest, and then, for the last mile, down a narrow country road into an area that became a new, but not better, place during my years of fishing there. Old houses and barns on farmland that had appeared to be in full retirement gave way to sprawling ranchers with sprawling lawns, cul de sacs, and two to four cars and trucks per household. The farmers were mostly gone. By Father’s Day 2000, the biggest crop in the area seemed to be chemically-treated grass. The road had been graded – all the stomach-tickling dips removed – and paved to impervious perfection and to a smooth glide to accommodate commuters who speed out every weekday morning. Some drive an insane two hours to their jobs. The new development – all those wells and septic systems – and the new road made me worry about their combined effect on my favorite creek. Would the wells diminish the flow of spring water into it? Would the septic systems leak and the bacteria seep into it? Summer rainfall on the new road would certainly send filthy, steamy drainage into the creek’s naturally cool waters. I harbored these fears – and they are legitimate fears – each time I visited Father’s Day Creek. But on the morning of June 18, 2000, I blocked out my concerns about human behavior and focused on finding trout. I had the place to myself.

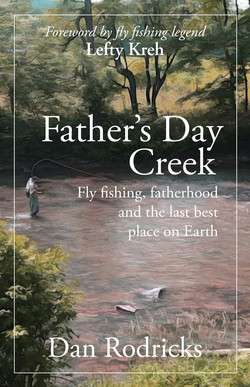

In case you are wondering about my credentials when it comes to fishing: I have done a lot of it. But I am not the late, great Lefty Kreh, the world-reknown Yoda of fly casting whose years as outdoors editor of The Baltimore Sun overlapped several of mine as a reporter and columnist there. I am not a professional angler or guide, and, while I have worked for newspapers for more than 40 years, I was never an outdoors writer. I am just a guy who has done a lot of weekday and weekend fishing, more than he realized until he did an accounting of it, though, it turns out, not as much as he would have liked.

Starting at age six, I fished for sunfish in a little brook in Massachusetts; hornpout, sunfish and bass in a mill pond; migrating herring in a herring run; cod and haddock, conger eel and mackerel in the deep sea off the New England coast; flounder in the bays near Boston, flounder in the Cape Cod Canal and flounder off a wooden bridge in Duxbury, Massachusetts, flounder off the Virginia coast; striped bass (also known as rockfish) near the Chesapeake Bay Bridge, in the Little Choptank River and Tangier Sound; stripers in a tidal creek on Cape Cod; smallmouth bass in the Susquehanna River (Pennsylvania side), shad in the Susquehanna River (Maryland side), shad in a tributary of the Susquehanna; smallmouth bass and rock bass in the Potomac River and the Delaware River; crappie and carp in three reservoirs; brown trout and rainbow trout in a dozen rivers in Pennsylvania, cutthroat trout in the Lamar Valley of Wyoming, rainbow trout in the Madison River of Montana and the Henry’s Fork of Idaho, brook trout in three ponds in New Hampshire; landlocked salmon and brown trout in the Androscoggin River (New Hampshire side), smallmouth bass in the Androscoggin River (Maine side); bluefish and speckled trout in the Chesapeake; hybrid rockfish in a Maryland farm pond; three kinds of trout in the rivers of western Maryland – the Casselman, the Savage, the Youghiogheny, the North Branch of the Potomac, Bear Creek, Muddy Creek, Lostland Run and Sideling Creek – and I’ve fished for bass in the farm ponds of southern Maryland; jack crevalle and snook in the tidal creeks of Florida’s Gulf Coast; false albacore off Montauk; bluefish in the surf of the North Carolina coast; and steelhead in the Salmon River in New York. I’ve caught brown trout in the Battenkill in Vermont.

I once awoke to the squawking of gulls, hundreds of them, on Cape Hatteras, and ran down to the beach to investigate the cause of the racket. It was minutes after sunrise, and a horde of bluefish had invaded the surf, attacking a school of Atlantic herring, chasing them into the shore. The tide had started to recede, stranding dozens of the herring in large, shallow puddles on the beach. My dog, a black collie-retriever mix named Rosie, hovered over one of the puddles, suddenly snapped up one of the silvery herring and ran off with it in her mouth. In the surf, the slaughter continued for another hour: Hundreds, perhaps thousands of bluefish feeding frantically on frantic herring, and the surf smelled of shredded fish. Another man might have instantly run to fetch his surf rod — you can catch a bluefish in its feeding madness with a bare hook, after all — but I stayed and watched a while. It was the blitz of bluefish the local anglers had told us about. I had never seen one. I tried to imagine the first Hatteras native to come upon this sight, way back when, at the dawn of everything. I imagined him running off to alert his tribe, then giving thanks for the feast that had come crashing ashore.

I did not catch fish in all of the places I just listed, but, as my friend Tom “Bush Hog” James used to say: “Fishin’ ain’t catchin’.”

That might sound like a copout – the motto of someone more interested in drinking beer than hooking bass – but Bush Hog was right about fishing. It’s about relationships and conversation, about comparing notes on life with others, about relaxing and getting your mind off the raucous world, the one that screams and roars beyond the ridge line above Father’s Day Creek.

Now, it’s easy to apply Bush Hog’s philosophy if you’re just sitting in a lawn chair by a pond or an ocean, or straddling a bench in a boat, waiting for a fish to strike your baited hook. It’s easier if your style of fishing is sedentary.

Fly fishing, on the other hand, requires lots of informed decision-making, physical dexterity for the cast, concentration and patience. There’s no sitting down, either. You have to hike to the good spots, wade into the water when you get there, stand and deliver your fly to a trout that is sipping bugs in the current and, therefore, vulnerable to deceit. I’d be lying if I said fly fishing wasn’t about catching. It is. But most of us do not kill the trout we fool into taking our flies. We catch them, look them over, maybe take a picture, and release them. I cast to trout in Father’s Day Creek to see if I can trick them into taking my fly, but also to make sure they’re still there, that they’ve not been decimated by poacher or plague. When they don’t bite, I get a little worried. I worry that the trout have scattered because the water temperature has been rising with climate change, or that some fellow from the horrid housing development nearby caught (and killed) a bunch of my fish with hooks baited with Velveeta balls, or that something fouled the stream when I wasn’t there to protect it. It could also be that I’ve been fly fishing long enough to have started losing my touch, but I doubt it.

Father’s Day Creek is a three-hour drive from Baltimore. I have neither right nor title to a single acre of the woods around it. And yet I consider the little river my own. I have felt protective of it, as if I were the hired riverkeeper, since the first time I set eyes on it.

The course of the river is varied in the most wonderful ways. Water ripples over a river bottom of brown gravel and decomposed leaf and wood, giving it the shade of dark tea. In some places, the water plunges into deep, spooky holes. It cuts sharply through a rock gorge crowned in hemlock. It rolls softly along a steep slope covered with wild rhododendron. There are places where it is no more than 20 feet wide, others where it opens to more than twice that width. In early spring, the current can knock you off your feet as you try to wade. In summer, the flow is greatly reduced but constant, and the water never seems to get warm enough to harm the wild trout that call it home. Light swarms of yellow insects emerge as evening falls in June, and trout rise to eat them. It is a beautiful, life-sustaining river that never seems to show the downstream effects of the usual upstream menaces – erosion from farming, trash from storm drains, an odor from a leaking sewer or waste-water treatment plant. That’s why I consider it the Last Best Place.

It sounds like a perfect place, and it almost is. But it almost wasn’t. And if there’s a lesson in this story, it’s at this moment in my telling – where trout meets man, and where man almost won.

Father’s Day Creek had a lot going for it, particularly compared to other rivers in the eastern United States. Since colonial times, the forests that served as their shade-providing canopies had been removed, and settlers turned the land into pastures for livestock and fields for crops. The loss of tree canopy exposed more of the river courses to the sun and raised the water temperatures. Erosion from farming, along with the comings and goings of wandering dairy cows, degraded the streams. That is primarily why so many rivers in the East are stocked with trout in the late winter and spring – the waterways become too warm and muddy to sustain the fragile fish for more than a few months each year.

Father’s Day Creek was different. It was in good shape; you might even say ideal. Because it was on private land, still protected by a rich forest, and because its source was still clear and cold, long stretches of Father’s Day Creek provided a perfect habitat for brook, brown and rainbow trout.

In May of 1993, during a Saturday night supper at my in-laws’ weekend home in the mountains, a fellow named Pierre told me about the stream. Pierre was a longtime friend of my wife’s family. My father-in-law and Pierre were both natives of France and both chefs in New York City who spent weekends at second homes in the Pennsylvania countryside. When he heard of my interest in fishing, Pierre bragged of his ability to take numerous trout from the nearby stream, and he invited me to join him and his friend, Roger, there the next morning.

I was eager to see the place. I arrived at 8 o’clock on an overcast Sunday morning. Daylight was just starting to seep through the hemlocks, but Roger and Pierre had been fishing for almost two hours. Roger used a white telescopic fishing pole, the kind that river anglers deploy in France. There’s no casting involved. You just extend the rod as far as you need to in order to drop your line and baited hook into a spot where the fish are likely to be. Roger wore boots but he had little interest in wading into the creek. He stood on a boulder beneath a large tree, extended his right arm and, still as a statue, held his rod in place until he felt a tug on the line. He slipped the trout he caught into a wicker creel on a shoulder sling.

Pierre wore a flannel shirt and rubber hip boots, and he fished with a spinning rod and a small brass lure shaped like a willow leaf. When he saw me, he grinned broadly and opened his creel – 13 killed, few more than 6 or 7 inches long, several of them wild brown trout.

“You’re lucky you don’t get arrested,” I half-joked.

Most of Pierre’s trout were probably under the minimum size required for harvest by the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania. He did not care about this.

“The smaller the sweeter,” said the chef in his French accent. “Oh, yeah, the little ones taste the best.”

“Yeah, and you have to kill twice as many to make a meal.”

He grumbled at my streamside moralizing and walked away, and, tell you the truth, I don’t blame him. The last thing he wanted on a carefree morning of fishing was a lecture on fishing ethics. There were several men along the river that day, and just about all were taking full creels of trout, both wild and stocked. The whole scene seemed greedy and depressingly short-sighted to me, and it threw me completely out of the mood for fishing. As a lover of rivers, I had learned enough about trout habitat to recognize what was happening that day: It was the purging of Father’s Day Creek.

From what I could tell, judging from Pierre’s and Roger’s creels and what I saw of other catches, about a third of the fish taken were the small brown trout born in the stream. The other two-thirds were larger, colorless, hatchery-raised rainbow trout. There’s a huge difference. The wild browns were natives, and vital to the stream’s sustainability; such fish should almost never be harvested from streams in the heavily populated Eastern states. The stocked rainbows, on the other hand, were just temporary visitors, placed in the stream for two reasons – to provide sport for anglers, and supper for their families.

The Commonwealth of Pennsylvania stocks more than three million adult trout annually in more than 700 rivers, mostly the old waterways considered unfit for a year-round wild trout population. But the stocking crews sometimes put hatchery trout in waters, like Father’s Day Creek, that are good enough for wild trout to inhabit all year. This is a huge mistake. It’s like putting paroled inmates in a nursery school. The rainbows compete for habitat and for food; they bring chaos to a delicately balanced ecosystem and stress the wild brown trout. It’s bad fisheries science, a concession to the fish-killers who use baited hooks and who want to catch stocked trout as conveniently and as quickly as possible – preferably in the same place their fathers took them when they were kids. They care more about maintaning their annual rituals and going home with full creels than about preserving a wild trout habitat, and the fisheries managers are pressured to accommodate that demand.

Stocking is an old tradition in the Eastern states. It is a widely accepted practice, and fisheries managers are caught between two forces – people, like me, who think wild trout streams ought to be left alone and the people who could care less about scientific arguments and look forward to fishing for trout in the usual spots every spring. I have always found it remarkable, and regrettable, that the men and boys who came out to fish during what they considered “trout season” did not care to enjoy the experience but for one day or one week all year long, nor did they care to know more about the rivers they fished. They had come to expect things to always be a certain way, even in nature, no matter how contrived the experience. Father’s Day Creek was, to the local guys, just an easy-to-access local river loaded with trout from the hatchery trucks. They expected the state to provide them with fish to catch, over a couple of weeks in April, and maybe May, and then they moved on to other activities. They could not imagine another reason to visit the river, or to even give it much thought; to them, the creek was simply a seasonal conveyer of easily harvested protein.

I’ve reached a point where I think the stocking should just stop in any stream that can hold wild trout. But, of course, such a decision would likely cause a revolt among the nation’s two-week trout anglers. I recognize that some streams are just too degraded, or get too warm in summer, to sustain wild trout. The state stocks those waters with trout so that adults and children can have a pleasant experience. Beyond providing that temporary recreation, however, I don’t see what good it does. I would rather see states curtail their stocking and put time and money into stream restoration efforts, to improve water quality and create more habitat for trout and other wildlife.

I make no apology for sounding like an elitist in this regard. Fishing is not only about catching. It’s about caring for the natural world around you, and having healthy waters for future generations.

Now and then, whenever I encountered a bait angler who seemed open to the conversation, I would explain some of my reasoning and talk about the challenges of catching wild trout all year in good waters, and how that ideal required the angler to stop fishing with bait and to release what’s caught. Instead of expecting the state to keep stocking degraded rivers with trout from a hatchery – a costly process that does nothing for the environment – we should work toward getting streams back to their historic best. Do that, and we could fish for trout every month of the year, and have cleaner waters flowing toward our reservoirs, lakes and bays. We might even reach a place where, with enough restored rivers, anglers who wanted to catch for their supper might be able to keep a couple of stream-bred trout. But until we do more to bring back more miles of healthy waters, we’re just financing and managing a cooked-up, half-baked system – stocking fish in rivers in spring to satisfy some seasonal craving for recreational fishing. It no longer makes sense.

That was my streamside rap, delivered with friendly discretion whenever it seemed appropriate. I tried to avoid making it sound like a lecture. I don’t know if I ever convinced a single angler to change his ways – to give up bait for artificial lures or flies, to leave his creel at home as a decorative vessel for dried flowers, and to practice catch-and-release fishing – but I tried a few times. I tried it with Pierre on Father’s Day Creek, but he was closer to my father and father-in-law in age and generational experience. He was a successful gardener who enjoyed harvesting the fruits of his labors, a chef who, like my father-in-law, took pride in preparing and serving good meals. The trout that he caught in Father’s Day Creek, whether wild or stocked, were part of his hunter-gatherer mindset, and as long as the state put trout in the river for the taking, Pierre would take them. And he would serve them, if you please, panned-fried in butter, with red potatoes and asparagus, and a glass of chablis.

The invasion of the hatchery-born rainbows was harmful to Father’s Day Creek. Dozens of fishermen, armed with lures and worms and little balls of Velveeta, came to its banks and caught them all in a matter of weeks. But here’s the thing: Like Pierre and Roger, these anglers made no distinction between the hatchery rainbows and the wild brown trout. They caught everything and took it all, stripping away the population of wild trout whose presence made the river so special. In 1993, I concluded sadly that, without protection by the Commonwealth, the creek would never be restored to its historic best. It would always be a marginal trout stream. It wasn’t sewage or erosion that harmed the river. It was short-sighted fisheries management and an indiscriminate harvest.