Читать книгу Father's Day Creek - Dan Rodricks - Страница 12

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление– 6:15 am

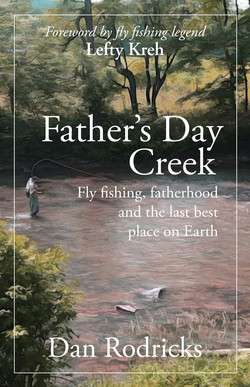

I usually fished the creek on weekends, and always made a point of being there on Father’s Day. I prepared by following the same fastidious ritual each time. I parked my car on a grassy spot near the old, one-lane bridge, pleased that no one else had the same idea. I stood outside the car and assembled my two-piece, 4-weight Scott rod and attached the Pfleuger reel. I ran the fly line through the eyes of the rod and checked the last section of the leader, the tippet, to see if it needed to be replaced or lengthened, or at least straighted. If the latter, I squeezed the line through a flat, bell-shaped leather line-straightener attached to my fishing vest. I placed the rod on the roof of my car while I finished setting it up. I attached to the leader about 18 inches of 5X tippet and, to that, an all-purpose fly, a size 16 Adams parachute, and secured it on the hook tender of the rod. Then I dressed for the occasion – chest waders and wading boots, the tan fishing vest that over the years had become way too heavy from acessorizing, with a net attached to a D ring below the soft collar. Then I checked to make sure my car key was in a zippered pocket, and I did this four times. It’s a strange habit but a good one; it guarantees I will not lock the key inside my car and spoil a day of fishing waiting for road service. Key secured, I headed for the trail down to the river. I’m a happy man when the trail appears overgrown with bushes and weeds. That means no one else has fished the creek for a good while. It was just that way on Father’s Day 2000.

I hope you can understand this feeling of being possessive of a place, of developing a sense of responsibility for it. Ownership is all in my head and my heart. I feel protective of the place, though I live 152 miles away from it and no longer visit as often as I once did. Father’s Day Creek is not simply a favorite fishing hole. It is a place I retreat to, in a pilgrimage of the mind, when there’s too much sad and bad news in the world, and especially in Baltimore, my adopted hometown. So one of my most valuable possessions is something I do not own. With the East Coast feeling more and more overcrowded and with rural vistas disappearing, I covet a spot that seems isolated and undisturbed, and I hope you know of such a place, or will seek one soon.

Of course, if I gave you the exact location of Father’s Day Creek, you could find it on a Google Map and see plenty of houses nearby – including Pierre’s and my in-laws’ – and a gas station and town center within a couple of miles. In fact, the area has become overdeveloped, with scattered housing and a strip of commercial clutter and grotesque suburbia in the midst of what was all farm country three decades ago.

The land around the creek has not been wilderness for going on 400 years. The trees are descendants of ancestors that fell to the logger’s ax long ago. The stream-bred brown trout – what I refer to as “wild trout” – are not a native species. They were introduced after the original inhabitants had been wiped out. The same is true of the small rainbows I sometimes catch; they were introduced to the stream, adapted to it and managed to reproduce. In fact, the only trout that could be considered native are the little brookies; those that swim in Father’s Day Creek today are likely the cold-blooded descendants of the brook trout that have survived the intrusions of settlers, loggers, farmers and hunter-gatherers.

I believe this because it fits with a wishful but informed perception of the creek – a stretch of private waters that seemed capable of a robust rebirth if the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania would only stop stocking it with trout, thereby discouraging human visitors. The potential reward seemed great for minimal effort, or no effort at all: If humans would stay away, the stream could be restored and the wild trout could grow in numbers and size. It’s what I believed. So I did my part. I stopped fishing in Father’s Day Creek. I left it alone. I wanted no part of the pillaging that took place each spring. I fished in other streams designated for catch-and-release fishing, and only with artificial lures and flies. This is one of the things you learn when you take up fly fishing. I do not know a single angler who fishes with a fly rod and kills trout. I am sure there are some out there, but I’ve yet to meet one. The reason is simple: If everyone who caught trout killed trout there would be no trout left, and every river would have to be stocked with fish from the hatcheries.

My father, of course, would never have understood this. He had been brought up too poor to understand it, and he had lived through a time when fish of all kinds appeared in endless abundance. In 1971, he caught a 36-pound cod off the coast of Massachusetts. That was not a grand-looking fish that deserved to be photographed, then quickly returned to the over-harvested Georges Bank to procreate. To my father, that cod represented a week’s worth of baked fish, Portuguese chowder and a pile of fish cakes. My father would not have bothered to fish Father’s Day Creek – small water and “dinky fish” – and he would have wondered why I spent so much time there, with so little to show for it.

This idea of claiming a piece of river that does not belong to you comes from boyhood fantasies. I had places I considered my own when I was growing up in a small Massachusetts town south of Boston. One was a fishing hole about 20-feet wide on the downstream side of a small bridge no more than 300 yards from my home. It was on a foul little brook that flowed from Forge Pond, north of the center of town, through woods and past an aluminum foundry owned by a neighborhood family, the Santillis. Years later, I discovered the stream on a map, and with a deceptively bucolic name, Meadow Brook. The place I recall was a backwater, and a good bit of it had been used as a dumping ground by the townspeople. My favorite pool was more like a small pond because the water was mostly stagnant; it flowed, ever so slowly, into a reedy marsh from where one of our neighbors, an adventurous scavenger and hunter named Secondo Mola, harvested large snapping turtles (for the eggs, and the meat for soup) and muskrat (for the pelts).

However unlovely, the little pool was mine, and that’s where I caught my first fish, a sunfish, on a yellow-and-green fiberglass pole that had been a birthday present from my uncle and godfather, Ralph Ortenzi, when I turned six.

I spent a lot of time around that homely pool in summer, watching turtles and frogs, and catching an occasional sunny.

I fantasized about setting up camp or building a little cabin beside the pool and keeping watch over it. I was not familiar with the term “riverkeeper” until I was 40 years old and visited Montana and, on a chilly day besides DePuy Spring Creek, smelled wood burning and stepped into a warming hut. That’s when I learned that some people are actually paid to manage fisheries; it stems from the British tradition of hiring “riverkeepers” to maintain and protect trout and salmon streams.

Lines 48 and 49 from Robert Frost’s “Birches” goes: “I’d like to get away from Earth awhile, And then come back to it and begin over.”

Frost said he would come back as a climber and swinger of birches. I would come back as a riverkeeper on Father’s Day Creek, and, in that fantasy I would have started my career at age 7 or 8, back in East Bridgewater, along little Meadow Brook.

East Bridgewater – population 8,500 when I lived there – did not offer much in the way of trout fishing. But it provided a lot of other things: A nurturing base for growing up and a sense of the big world beyond, if only from the sound of the train coming through, blowing its whistle as it passed during the night.

Sometimes the train stopped at the Woodward & Wright Last Company – they made wooden lasts, or forms, for shoes there – and I only knew this because, on the way to school the next morning, we walked over the tracks, and there would be burned-out road flares with piles of ash next to them; workers from either the train or from Woodward & Wright had set them out the night before. I cannot say I ever saw the train come through town. But I certainly heard and saw evidence of it, and it fostered wishful thinking about the future and the notion of moving on.

Some people have it all planned by the time they arrive at senior year in high school. For others, it just happens – college or a job takes them away. Or maybe they fall in love and part of the deal involves settling somewhere else. Some people moved away from East Bridgewater in one damn hurry – a couple of my classmates were never heard from again after graduation night – and others were not so sure about leaving the hometown.

But all who grew up in East Bridgewater took a piece of that small, simple and mostly delightful place with us.

Looking back, a lot of it seems idyllic now – playing outside all day in the summer until it was dark, inventing games, walking “up town” to buy a popsicle, riding my bike through woods and across fields, pretending I was Steve McQueen on a motorcycle in “The Great Escape,” going to the polo grounds for the Fourth of July bonfire. One year, when John F. Kennedy was president, the East Bridgewater Commercial Club gave JFK’s rival in the Cold War a hot seat: They capped the town’s annual 40-foot bonfire with an outhouse, and inside, seated on a toilet, his red Communist Party necktie flapping in the summer breeze, was an effigy of Soviet premiere Nikita Khrushchev.

We played Little League games on the old polo grounds and, at the time, there was no Mercy Rule to bring a game to an early end when one team had an insurmountable lead. The adults in East Bridgewater must have thought a good lickin’ was just part of life, just what we needed, a rite of passage for eight-year-old boys. So the games would go on and on, 15-0, 26-2, 36-3. I played for the Woodard & Wright Last Co. While we appreciated the team sponsorship, we found ourselves at a distinct psychological disadvantage, having the word “Last” sewn into our jerseys. And that was where we ended up that first season.

The fall in East Bridgewater brought high school football games and the smell of burning leaves. The winters were long, snowy, rainy and gray and, for long stretches, muddy and miserable. Plymouth County had an average annual average snowfall of 37 inches, and it was not unusual to get a foot of snow overnight. But life mostly went on, we mostly went to school after a big snow. And it was the short, stout, ruddy-faced man named Eddie Kenneally who saw that we did. If there was snow overnight, you knew there was a chance the schools might be closed. But if, by 6 am or so, you heard a cowbell out front, if you heard a man barking, “H’yar,” and, if you could feel the thud of big horse hooves, strong and heavy through the snow, you knew you were going to have classes that day. To confirm it, you rubbed the frost off a window so you could see Eddie Kenneally driving his huge draft horse on a sidewalk plow, his Dalmatian scampering alongside him in the snow.

As much as we appreciated a day off now and then, school was really the central part of the East Bridgewater experience – where you made friends, and where I had the good fortune of having some really great, committed teachers. When I take account of people who had the most influence on me – who took an interest in me, supported me – six of the Top Ten were teachers in the East Bridgewater public schools.

Spring meant the end of mud time, ice-out at Forge Pond, fishing for hornpout, Little League parades, trying to catch herring in a herring run with our bare hands, and failing every time.

The summer meant endless backyard baseball games and hanging out at my little piece of Meadow Brook.

I thought about the place so much – almost as much as I thought about baseball – that I took it to bed with me as I reviewed all the activities of a busy summer day. I imagined that I would construct an observatory alongside the pool. I would dig a big hole next to the brook and insert a large steel container, like an underground storage tank. My father was a foundryman, and the Santillis made castings from aluminum; certainly they would help me acquire the steel tank, outfit it with an air vent, a topside hatch door and watertight observatory window, then dig away the bank between the window and the water. From inside the tank, which I planned to line with blankets and pillows, I would be able to unravel the mysteries of the pool by regarding all of its comings and goings. My strategic plan included, eventually, charging admission for others who wanted to watch the fish, turtles, frogs and muskrat from my private observatory. However, I would reserve the right to ban any neighborhood kids who had mocked the idea, starting with the local wise guy, Stevie Abatti. No way was he getting a seat by the window.

I sketched plans in a notebook. I showed my father. I showed my older brother, a scientist still in graduate school at the time. While the reactions were encouraging, I never got the funding I needed. But the scheme has never left my mind.

There was a second place in East Bridgewater, also by a river, that I considered my own, and it was just another five-minute walk further up West Union Street, toward a place known as Cinder Hill because there used to be an ironworks with a big furnace in the area. There was a spot on the Matfield River where, in summer, I would wait in the mud to catch crayfish in a Maxwell House coffee can, and I approached my quarry with such intensity I was pretty much oblivious to the odor of sewage. To some people, it was the polluted old Matfield; to me, it looked like a pristine white-water river from a New England calendar on the wall of a barbershop. Despite the reality – foul water, devoid of fish, debased by years of industrial use and human waste – I dreamed about building an underwater observatory there, too.

I agree that the Matfield looked a lot better than it smelled. But the smell was not as acute in winter, when I trekked alone through the snow to snoop around in the woods and along the floodplain. I considered it my private scouting grounds, and my discoveries included bird nests on naked branches, rabbit tracks and what turned out to be the ruins of one of the town’s 22 long-abandoned mills. The one by the Matfield, I later learned, had manufactured arms for the Revolutionary War.