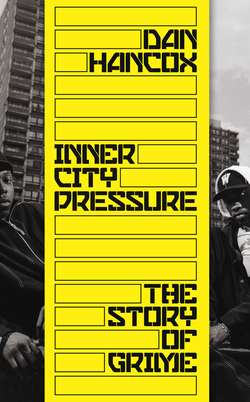

Читать книгу Inner City Pressure: The Story of Grime - Dan Hancox - Страница 11

THE CITY AND THE CITY

ОглавлениеI’m from where Reggie Kray got rich as fuck

East London, who am I to mess tradition up?

Jellied eels, pie and mash, two pints of that Pride on tap

Polo top, pair of Stans, flat cap and a Burberry mac

Back when Lethal Bizzle was Lethal B

This is how we used to dun the dance in East

We used to spit 16s till they called police

Probably somewhere in a party or a dark shebeen

Kano, ‘This Is England’

In the Museum of London Docklands, five minutes from One Canada Square and the shimmering glass totems of Canary Wharf, among the exhibits on slave owners and sailors’ rebellions, tall ships and frost fairs, hangs a painting of the river made in 1883 by William Lionel Wyllie. It shows barge workers shovelling coal in the shadow of a clutter of trade ships, the river alive with noise, fumes and activity – the painting is titled: Toil, Glitter, Grime and Wealth on a Flowing Tide.

It’s easy now to forget that London was, for most of its 2,000-odd years of life, not just a working city, not just an industrial city, but specifically, a port city. The world’s dry dock; the shoving-off point for innocent expeditions and brutal subjugation. And as the title of Wyllie’s painting suggests, port cities have a few consistent attributes: one is transience, a constant clamour of people leaving and arriving, drifting in and out with the tides. Another is inequality – rags and riches, a halo of insalubrious low-level criminality, insobriety and dirt hovering around the glittering cargo – or a halo of enriching gold around the squalor and decadence, depending on which way around you look at it. Either way, one travels with the other, one lives with the other. A hundred and twenty years later, Wyllie’s namesake would use some cheap computer software and a microphone to document the same toil, glitter, grime and wealth flowing through twenty-first-century London, at 140 beats per minute.

Some cities are divided between distinct geographical binaries. North and south. The centre and the suburbs. Uptown and downtown. The shanty towns and the gated communities. London is not easily disentangled: it weaves its divisions into a fine mesh, like the netting that stops pigeons gathering underneath railway bridges. The council tower blocks are mingled in with the multimillion-pound mansions. The greasy-spoon caff that’s been there since the seventies stands next door to the refurbished gastropub charging £15 for a Sunday roast. The grandiose seventeenth-century church faces down the night-time den of iniquity.

When widespread rioting erupted across London and several other English cities in August 2011, the writer James Meek reflected on an incident that he’d witnessed a few years before in one of Hackney’s most prominent new bouji enclaves, Broadway Market – when a group of 30 tooled-up black teenagers, chasing two enemies with a hand gun, suddenly entered (and quickly departed from) the lives of the white middle-class people sipping wine at the outdoor tables. ‘It is as if the council-owned tower blocks and estates behind, around and in-between the gentrified patches, where less well-off and poor people live, belong to some other dimension,’ he wrote. ‘Loving the cultural diversity of London as a spectator-inhabitant is not the same as mingling with it. The yuppies don’t go to the white working-class pubs, and the white working class don’t go to the yuppie pubs … this isn’t mixing. It’s the ingredients for something – nobody knows what – laid out side by side and not being mixed, not touching.’1

London was in an unsettled temper at the start of the new millennium. It had survived the much-feared but unknowable threat of the Millennium Bug, but suffered the embarrassment of the Millennium Dome, and the damp squib of a Millennium Eve ‘river of fire’ on the Thames that was supposed to be visible from space, and wasn’t even visible from the Embankment. The clock ticked over from 1999 to 2000, planes did not fall out of the sky, and the world didn’t end – but some more slow-burn changes were starting to take shape. In May, the British capital acquired an elected Mayor for the first time in its history: Ken Livingstone shook off the contempt of Prime Minister Tony Blair, resigned from the Labour Party, and ran as an independent against the Conservative Steve Norris, and the candidate from his own party, Frank Dobson – beating both comfortably. London had a new City Hall, and a maverick left-winger and newt obsessive in the Mayor’s chair.

Two days after Livingstone’s victory, to the annoyance of maturing dance music sophisticates everywhere, Oxide and Neutrino’s frantic ‘Bound 4 Da Reload’ – with a chorus built around the theme tune from TV hospital drama Casualty, sampling a silly line from gangster flick Lock, Stock and Two Smoking Barrels, and peppered with gunshot noises – entered the charts straight at number one, flicking a V-sign at the music establishment. The UK garage scene which the two young south Londoners had emerged from had previously prized refinement, romance, aspiration and an urbane multiculturalism above all else. But clean lines, shiny shoes and champagne were being replaced with something much darker, and murkier – just as the city itself was about to start moving in the opposite direction. A new sound was about to muddy the waters of UK garage’s infinity pool, just as the new Labour government, indeed the New Labour government, were hatching grand plans to drastically smarten up the inner city forever.

In the late 2010s, we tend to look at the cranes going up around London and assume they sprouted from the city’s chalky soil, or we gaze wearily upon the prettified glass towers of luxury flats, the pop-ups and the hipster cereal cafes and assume they landed out of the clear blue sky. But urban change is not like the weather, and gentrification is not organic, inevitable or natural. The new millennium began with grime’s inner city on one side, and an entirely different, largely new kind of inner city growing rapidly to take its place: expensive, monocultural, private, surveilled and planned from the very top by Tony Blair’s government.

At the time, inner London was the richest region in the European Union, yet alongside citadels of banking wealth like the City of London and Canary Wharf were some of the most deprived council estates in the country. Long-standing economic and social divisions were intensifying, as the changing winds of late capitalism induced the middle classes to begin moving back from the suburbs and the home counties. They were about to get a big push from the government, who wanted to make the inner city the engine of bourgeois modernity, cosmopolitan culture and aspiration – the essential spirit of what was self-consciously referred to as the New Labour ‘project’.

The reality on the ground as Blair took office was not good. After 18 years of Conservative government, social problems and hardship were thriving in British cities, and in the country at large. By the mid-nineties Britain had more children growing up in unemployed households than anywhere else in Europe, and the highest teenage pregnancy rate. Child poverty had trebled between 1979 and 1995, the number of drug addicts quadruped in the decade to 1996, and the number of homeless people sleeping on the streets had soared.

Since the deregulation of the City in the late 1980s, London’s role as Britain’s primary economic engine had been greatly magnified: by the millennium, earnings in the capital were on average a third higher than the rest of the country. But the divisions were greater, too: Londoners had a higher unemployment rate than the national average, and a much higher proportion of children growing up in households with no income: 36 per cent of children in inner London lived in workless homes in 1999 – compared to 17 per cent nationally. London households were also more likely to be overcrowded: 16 per cent compared to 6 per cent in other English cities.

In east London, the area that will always be most associated with grime, the boroughs of Hackney, Tower Hamlets and Newham have consistently appeared among the most deprived local authorities in the entire country; in 2000, the government used a new, complex model for analysing different aspects of poverty, from housing to health, which they called Indices of Multiple Deprivation. Across all of England, the grime boroughs were ranked at 1, 2 and 3. A medal-winning podium of poverty.

‘East London is in need’ has been the received wisdom of London local government ever since it was first introduced in 1888. A century and a half ago, Tower Hamlets was home to the disease-ridden squalor, vice, filth and overcrowded warrens of the infamous Old Nicol slum, before it was finally demolished in the 1890s, following the Housing for the Working Classes Act. The slum clearance programmes continued for decades, both before and after the devastation of the Blitz; some residents moved out to the suburbs, others were given low-rent social housing in the modern new council estates being built. Between 1964–74, the last of the slums were demolished and the Greater London Council built 384 tower blocks of ten storeys or more, providing 68,500 new flats. They were accompanied by utopian rhetoric about a new way of living and ‘streets in the sky’, changes that would finally grant the dignity London’s working-class communities deserved, and dramatically lift the quality of life. In 1981, at the peak of the social-housing boom, there were over 75,000 council homes in London, housing nearly 31 per cent of the capital’s population. It is no coincidence that they were heavily concentrated in exactly the boroughs where grime and UK rap would later thrive: 42 per cent of London’s social housing was in ‘Inner East London’: the boroughs of Hackney, Newham, Tower Hamlets, Islington, Haringey, Southwark, Lambeth and Lewisham.

London has historically been a fairly low-rise city, with relatively few skyscrapers, landmark blocks of luxury apartments, or high-end hotels and offices – it has not looked like Manhattan, or latter-day Dubai, Hong Kong or Shanghai. Largely this was by design: planning laws have prohibited tall structures which obscure certain ‘protected views’ of iconic old London landmarks like St Paul’s and the Palace of Westminster, as seen from certain high points on the fringes of the capital, like Parliament Hill, Richmond Park and Alexandra Palace – it’s not the specific views themselves which matter so much, but their utility as insurance against a cluttered skyline.

But at the start of the new millennium, a new kind of high-rise building started arriving in the capital: one much less likely to produce exuberant forms of youth culture, clad in glass rather than concrete. Most obvious amongst them was the Shard – Mordor-upon-Thames, owned by Qatar, an obscene 72 storeys high, built with the enthusiastic support of Ken Livingstone, and the backing of New Labour. This directly contravened the ‘protected views’ regulations; English Heritage objected at a public inquiry, and were ignored. At the time of writing, five years after opening, all ten of the £30–50m flats on the tower’s upper floors remain unsold, and empty. Even a visit to the viewing deck costs more than £30. Since then, the trickle has become a flood: in 2017 a survey found that 455 new high-rise blocks were either planned or already under construction in London: ‘safety deposit boxes’ for wealthy investors, expensive hotels, high-end office space and luxury flats. Blocks like the ickily-named Manhattan Loft Gardens in Stratford followed the Shard’s lead and caused controversy by ruining another sight line of St Paul’s. More importantly, not a single one of the 455 was being built to provide housing for London’s poorest.

The Shard started a bold new trend – building hideous neoliberal obelisks which London didn’t need – but the major precedent had already been set: the planting of Canary Wharf’s towers of misbegotten riches, right in grime’s back yard, in place of the city’s abandoned docks. Today, underneath the white office lights and CCTV cameras of what is sometimes known as the ‘second City’, teem the ghosts of empire, hard labour, hard liquor, opium dens, sailors and sex workers. Even as it enters adolescence, Canary Wharf’s cluster of gleaming skyscrapers still feels like a life-size artist’s impression, rendered in three dimensions; free from clutter, free from litter – and free from heavy explosives, you presume, if the security presence is anything to go by.

Look closer, and some of the police aren’t actually the police at all – they’re private security guards, in uniforms designed to look exactly like real police uniforms. The whole area is unnervingly clean. As close as it is, Canary Wharf is almost completely sealed off from its neighbours to the north, where grime erupted into life – Poplar, Limehouse, Bow, and eventually Hackney and Newham – separated by the huge A13 and A1261 dual carriageways, and a no man’s land of train lines, Docklands Light Railway sidings and buildings, business parks, car parks, blind alleys and dead-ends, all of which act as further barricades. It is almost as if the builders of Canary Wharf wanted it that way. ‘That’s where all the yuppies are,’ MC Breeze from Roll Deep says in a 2003 documentary, pointing up at One Canada Square. ‘We’re just over the road, and it’s one of the worst boroughs in England.’2 On the south side of the skyscrapers, in a part of the Isle of Dogs which used to be known as ‘The Land of Plenty’ during Britain’s colonial heyday, the Anchor & Hope pub (Est. 1829) sits boarded up and unloved, its business perhaps swallowed by the two-storey Thai restaurant next door – the hope is gone and the boat is adrift. Commerce spares little attention for sentimental attachment to the past – even its own.

East London’s past is weighed down with poverty, and weighed down with heavy industry: the docks, of course, but also gas, railways, manufacturing, textiles, mills – and, a rare example which is still clinging on today, the Tate and Lyle sugar refinery. It has always been the city’s working quarter, with an abundance of low-paid, physically punishing jobs, and was not just the arrival point for immigrants and internal migrants, for centuries, but also the place where many of them made their first homes in the capital: always more multicultural than the rest of London, and almost entirely working class.3

East London’s industrial history continued to loom over the area once all the industrial work was gone. Even without the factories coating nearby buildings in a layer of soot, and the industrial pollution and jetsam from the docks, east London remained associated with grime, dirt, grit and debris. The connection between the word, the music genre, and the places where grime came from has always been understood to be obvious. ‘Most grime tunes are made in a grimy council estate,’ MC Nasty Jack told an American documentary crew in 2006. ‘Mum ain’t got enough money, everyone’s just angry. You need a tension release.’4 The name of the genre aside, grime has featured a whole range of lyrical tropes in which dirt is lionised: tunes are praised as mucky – mucktion, as a noun – dutty (dirty); Shystie even proclaimed one of her tunes was ‘muddy’. Partly this is about paying tribute to the sonic ‘bottom end’, the sub-bass, but it’s also a testament to the music’s geographical origins.

The East End had been very literally grimier in the past – as in the great smog of 1952, where coal smoke and bad weather conspired to kill around 12,000 Londoners. Regeneration and grime are oppositional forces in the urban arena: in the recent vernacular of urban planning, the word ‘regeneration’ has always been understood as a response to grit, grime, disorder, clutter and failure or decline. It has a Christian moralistic aspect, a sense that the city too can be born again, that it might – with the right purpose and guidance from above – dunk its head in the water and repent its poverty and sin. Indeed the first recorded use of ‘regeneration’ in English is from the Wycliffe Bible of 1384, describing the kind of rebirth that Jesus’s disciples can expect upon reaching heaven. It was the perfect word for New Labour and the secretly evangelical Prime Minister: grime was old Labour, 1970s, strikes and coal, rubbish piling up in the streets, sin and concrete; regeneration was pastel colours and cheery post-modernism, IKEA urbanism that would make the city look like a kids’ play centre – and entice the middle classes to come and live in it.

The East End’s underdog mentality, marginality, poverty and history of industrial squalor are all interconnected. Macho resilience and physical and mental toughness have long been fetishised as traits specific to east London, and that kind of grittiness is prominent in grime’s vernacular. Dizzee Rascal’s single ‘Graftin’’ addressed listeners inside and outside the capital, and proposed grimy London as a more honest alternative to the scenes on the city’s tourist postcards:

Young hustlers, London city, stand up

L-D-N, they know us in the world

You know what time it is

I swear to you it ain’t all teacups, red telephone boxes and Buckingham Palace

I’m gonna show you it’s gritty out here5

Almost everyone involved in making grime since its early days has, at one point or another, said something along the lines of ‘I don’t know where the name came from, I didn’t really like it, but it just kind of stuck.’ Musicians will almost always do this anyway – disavow all genres and taxonomy, unwilling to let their free-flying creativity be pinned down behind glass and labelled. It’s understandable. But there is another (equally understandable) motive for rejecting the name. Unlike UK garage, grime wasn’t explicitly aspirational in its fashion or its ethos. But all the same, when it first emerged, the word ‘grime’ seemed to undercut a basic need for respect. What you can hear in the disavowals of the name is ‘We’re trying to push ourselves out into the world and show we’re worthy of respect, because we don’t get any – and this word marks both us and our work as unsavoury. Why would you be proud of being dirty?’

Legendary UK garage DJ EZ is thought to have – semi-inadvertently – named it on his KISS FM show, describing some tracks as ‘grimy garage’, until the word ‘garage’ eventually fell away. No one’s entirely sure. What is certain is that EZ wasn’t alone: describing the music that way was fairly normal among DJs and MCs in the early 2000s, before anyone agreed that grime was called grime – you can still hear it now, on classic recordings like Slimzee’s 2002 Sidewinder tape pack set with Dizzee and Wiley (often, correctly, hailed as the greatest mixtape ever made). ‘This one’s dirty, this one’s mucky,’ says Dizzee as Slimzee wheels in another tune – Dizzee, of course, named his label Dirtee Stank.

‘East London’s quite a poor area,’ DJ Trend, aka TNT, told a BBC Radio 1 documentary about the still-unnamed emerging scene, broadcast in 2004. ‘So a lot of the kids, they don’t find nothing else to do, so it just leaves one thing: MC and listen to pirate radio stations.’ The music being made by these young people was a reflection of ‘what you see when you wake up in the morning,’ he continued. ‘Most people that’s what they’re seeing: a lot of grime in the area, a lot of grimy things happening.’6

Throughout its history, the East End was the impoverished edge of a wealthy city; but it was also, as the twentieth century drew to a close, the home of the largest piece of urban regeneration in Europe – a project that would help set the tone for all development projects in London in the years that followed. After thriving for centuries, London’s docklands collapsed in the space of about two years in the late 1960s, when the work was moved further east down the Thames, to Tilbury docks in Essex. The standardisation of shipping containers ushered in a new phase of global capitalism – it suddenly became ten times as fast to load and unload ships, and could be done with far fewer hands. 83,000 jobs were lost in the docklands boroughs in the 1960s alone, and as people left in search of work, the area became a desolate post-industrial wasteland: the ‘wild east’ of classic British gangster film The Long Good Friday, filmed around what would eventually become Canary Wharf, during its long interregnum of abandonment and decay. The docklands were indicative of the ‘developing sickness of our society’ Conservative Shadow Chancellor Geoffrey Howe said in 1978, adding that ‘the dereliction is itself an opportunity’. Three years later, the Thatcher government set up a mega-quango called the London Docklands Development Corporation (LDDC) to take charge of what was at the time the largest urban regeneration in the world. After more than a decade of urban planning tug-of-war, and substantial protests from parts of the local community, in the nineties Canary Wharf slowly began to take shape: a district of skyscraper-dwelling superbanks and legally dubious white-collar profiteering, patrolled by private security guards. A new kind of urban space for a new London and a new millennium.

One Canada Square, the actual name of the fifty-storey, pyramid-topped building often identified as ‘Canary Wharf’, was completed in 1991, and became the UK’s tallest building, the most visible legacy of Thatcherism, towering over London. It was not until the first years of the new millennium that Canary Wharf really fulfilled its destiny as ‘the second City’, and took on a life of its own, outstripping the old City of London (the capital’s traditional financial centre, around Bank and St Paul’s, with its antiquated heraldry, liveries and rituals), and becoming the home of the newer, much more dangerous unregulated financial speculation that would be instrumental in creating the global financial crisis of 2008. Peter Gowan called it ‘Wall Street’s Guantánamo’, a lawless bolt-hole where firms like Lehman Brothers could get away with complex debt-repackaging and trading they would never have been allowed to pursue in Manhattan.7

In a neat example of the laissez-faire capitalism which led to the financial crisis itself, the building of Canary Wharf itself benefited from special government exemptions on rates, tax and a speeded-up planning permission process. No questions and no regulations. It was to be the Big Bang of urban regeneration – creating not just the bankers’ skyscrapers that watched over the grime kids, the yin to the estates’ yang, but also a new airport aimed at business-class customers (London City Airport, opened 1987), the Docklands Light Railway (1987), the Jubilee Line Extension (1999) and the ExCeL conference centre (2000). The LDDC was the flagship of the hyper-gentrification that would follow across British cities, legitimising New Labour’s urban renaissance, of which the renovating and demolishing of council estates was also a vital part. Canary Wharf’s tower blocks were barely a couple of miles from the council blocks where the pirate radio aerials were going up, but ‘the second City’ was never designed to have a relationship with its neighbours: the attention was turned towards its rival and parent. Canary Wharf was deliberately laid out so its ‘central axis’ – a gap in the two tower blocks facing One Canada Square – looks out across a fountain, and lines of trees, towards the City of London.

The arrival of Canary Wharf coincided perfectly with changes in the financial world, as greater deregulation, coupled with new technology, created new markets for global capital and financial services. London was especially well placed to take advantage of these – not just because of Britain’s historic global and colonial power, and the corollary dominance of the English language, but also because it was in a critical time zone between New York and Tokyo. The likes of the Bank of China, Bear Sterns and Morgan Stanley moved into One Canada Square, while next door, the Lehman Brothers were housed in the 30-storey tower at 25 Bank Street.

It is largely forgotten now, but there were protests against the LDDC throughout the eighties and nineties by local people, especially in the Isle of Dogs, as well as alternative ‘people’s plans’ for developing the area in a way that benefited the communities who lived there, rather than itinerant hedge-fund managers who would move in for a couple of years, before going on to Hong Kong or Frankfurt. The locals were ignored. ‘There may well have been other ways in which the regeneration of the area could have been secured,’ admitted the LDDC in 1997, but these ‘would have perpetuated rather than solved the problems of east London’.

The ‘problems of east London’? Social housing and social housing’s fellow traveller, poor people, who unfortunately placed ‘added pressures on the resources of the local authorities’. Instead, the regeneration had transformed the area from somewhere previously ‘isolated both physically and emotionally from the rest of London’ and placed it ‘well and truly in the mainstream of metropolitan life’.8

The LDDC spent £3.9 billion of public money on the Canary Wharf regeneration, only to seal it off from its disproportionately sick, unhappy, overcrowded, addicted, jobless and impoverished neighbours.

For those Londoners too young to remember the area before the skyscrapers of Canary Wharf, it feels like it’s always been there, with One Canada Square’s blinking top-light our city’s modern lighthouse. Canary Wharf is less than two miles from the notorious 25-storey, three-tower block Crossways Estate where Dizzee Rascal and Tinchy Stryder lived as children (‘the three flats’), and less than a mile from Langdon Park School, where the former wrote the beginnings of Boy in da Corner in music class. Interviewed in 2010 for a BBC London radio programme about ‘the best and worst of the capital’, Dizzee was asked to nominate his favourite building in London, and unhesitatingly chose One Canada Square:

‘It means the most to me, I could see it from all angles as a kid. That was the highest building I could see from my bedroom. And when I see it from south London, when I’m coming over from the Blackwall Tunnel, it always gets me excited, especially at night – it feels special. I love that and the buildings around it – you see a little mini metropolis being built up … It’s not quite as impressive as New York or Japan, but it’s ours, innit? I remember when we were little, we had a conspiracy, we thought that thing on the top of it was like aliens, and they were about to fly off – loads of little theories like that. We’d blink and think they had lasers up there.’9

It’s not a stretch to suggest that Canary Wharf was the source of grime’s unique incarnation of Afrofuturism; the African diasporic aesthetic that takes science fiction as a tool for discussing oppression and freedom – where spaceships might be a metaphor for slave ships, subverting the journey to make it one of escape, not damnation. It’s a futurism you can hear in the constant injunctions in grime to ‘push things forward’, to ‘elevate’, to make music – and to be – ‘next level’, and it dovetails with the competitive rhetoric enshrined in Canary Wharf’s giant totems to late capitalism. Contrary to American hip-hop’s rootsy rhetoric about being ‘real’ and knowing and respecting your history, grime is a year-zero sound, which – in its early days, at least – asked only what’s next, and sought to get there first.

You can hear this Afrofuturism most of all in the sonics of grime production – the stark, unfiltered minimalism of the kick drums, the interplanetary weight of the bassline, the sleek raygun zaps and zips of a synth, the way the whole edifice shines sleekly like a spacesuit. It’s the sound of the future kids have dreamed of for decades, even while grime’s lyrics describe with molecular detail the dirt of the MCs’ vividly quotidian lives; MCs who were not universe-traversing spacemen, but teenagers growing up in the poorest boroughs in the country. The real meaning of Canary Wharf, rather than its laser-shooting sci-fi potential, was not lost on Dizzee’s peers in the east London grime scene.

‘Canary Wharf is like our Statue of Liberty,’ Roll Deep’s DJ Target told the Guardian in 2005: ‘It pushes me on. It’s like all the money is there and it’s an inspiration to get your own.’

Target is now a BBC 1Xtra DJ, which might seem like a token victory for the twin myths of trickle-down economics and climb-up philosophy that Canary Wharf and Britain’s political classes so aggressively pushed. New Labour’s architect Peter Mandelson infamously defined what was ‘new’ about the party when he said, in 1998, he was ‘intensely relaxed about people getting filthy rich’. British politicians have long perpetuated fallacies about social mobility, the ‘aspiration nation’ (a favourite slogan of David Cameron when he was PM), or the £9-billion 2012 Olympics ‘inspiring a generation’ out of poverty, but there is no clearly articulated British equivalent of the American dream – for which US rap music has been such a strong shill. In the UK, the relationship is less overt than the familiar American alliance of multimillionaire ‘ghetto’ musicians and multimillionaire financiers: the kind crystallised in The 50th Law, the self-help book by 50 Cent and best-selling ‘power strategist’ author Robert Green. But it is there. For the teenage Dizzee, Canary Wharf’s blinking white light held the potential for an alien getaway, but it was also perhaps east London’s version of the green light at the end of the dock in The Great Gatsby, a symbol of ‘the orgastic future that year by year recedes before us’, the tantalising dream of escape into a brighter tomorrow.

Slimzee, perhaps grime’s greatest ever DJ, with his childhood friend Geeneus one of the founders of Rinse FM, tells me they had other dreams for the tower. ‘We always used to look up at Canary Wharf, when we were growing up, and I wanted to go up to the top and put an aerial up there.’ He pauses, amused at the obviously flawed teenage ambition. ‘But you couldn’t: it’s got that sloping pyramid roof, it wouldn’t work.’

Tinchy Stryder, who grew up in the Crossways Estate, says Canary Wharf dominated the skyline. ‘When I was growing up you could see it everywhere. We felt like, “Oh, wow, do we get to go there one day?” It felt really close, but far away at the same time; like, it wasn’t really anywhere for us to be. Everything felt fresher and cleaner than where we grew up; it felt like a different world. It felt like when you go there, you had to be on your best behaviour.’ And he was right – the paved terrain around the skyscrapers was a paradigm for what have become known as ‘POPS’, privately owned public spaces: where private security guards can ask you to leave just based on looking at you. If Detroit techno captured the metronomic industrial rhythms of the city’s car factories, grime’s sonic palette describes the dystopian scene in millennial east London: the view from the decaying tower blocks down onto the de-cluttered spaces and privatised plazas of Canary Wharf – gleaming, futuristic, and glowering with menace.

When the BBC filmed a short profile of Dizzee to be broadcast as part of the 2003 Mercury Prize TV show, they caught him looking out of the window of the Crossways Estate with a less light-hearted attitude to the second City than he would display by the end of a decade, once he’d reached a state of monied grace: ‘That is Canary Wharf,’ Dizzee explained to the camera. ‘It’s in your face. It takes the piss. There are rich people moving in now, people who work in the City. You can tell they’re not living the same way as us.’

New luxury flats and gated residential blocks were sprouting rapidly in the foothills of Canary Wharf throughout the 2000s; like Target, Dizzee was under no illusion about the lesson to be learned from Canary Wharf, malevolent or not. He was asked in the same BBC Mercury Prize interview what motivated him. He stared straight at the camera. ‘Money motivates me. I’m motivated by money.’ A year later, on the B-side to ‘Dream, Is This Real’, he summed up the ethic of the age:

We was kids, we was young, used to love having fun

Now we look up to guns, and the aim’s only one:

Make money, every day, any how, any way

I tried to choose the legal way10

Those rich people who ‘don’t live the same way as us’ (and don’t always choose the legal way, either) arrived in droves, to the point that by the 2010 election, the Tory candidate for Poplar & Limehouse, Tim Archer, an HSBC banker on sabbatical from his office in Canary Wharf, was the bookies’ favourite to win. It would have been the Conservatives’ first victory in any Tower Hamlets seat in decades. Intrigued by this daring incursion of the banking set into their grimy new neighbourhood, I went on the campaign trail with Archer and his team. To the surprise of Conservative HQ, they failed to win Poplar & Limehouse. One of the main reasons for their defeat was that they couldn’t get access to the new blocks of luxury flats; there were so many entry-phones and security gates they weren’t able to canvass and recruit the very people who were supposed to be helping them win. It was almost as if the new arrivals didn’t give a toss about the area they’d moved into. One of those new luxury blocks for the international super-rich, a development called Pan Peninsula, promises buyers ‘a view that few will share’, and that unlike the teenagers gazing up at Canary Wharf’s blinking eye, residents will ‘look up to no one’. The spiel on their website promises you will:

Inhabit a private universe. Where luxury apartments combine with a spa, a health club and a cinema to create an urban resort. Where service is tailored to need, and bends to individual will, effortlessly and invisibly. Where business and play happen high above London. Live at Pan Peninsula, exist in another world.

It perfectly articulates the mentality of Canary Wharf: where everything – and everyone – bends to the will of those who can afford it.

‘Coming from where I come from, you didn’t feel a part of London,’ Dizzee told BBC London in 2010. This is the essence of what it means to be marginalised; on one level, your hometown brings you pride – there are numerous grime songs paying homage to London as a whole, rather than just the local neighbourhood – but you are excluded from its most famous parts, the parts the tourists see, the parts the middle classes negotiate with ease and confidence. In this sense, grime both is London, but also excluded from its official narrative, invisible in the face the city shows to the world.

To prove London wasn’t all ‘teacups, red telephone boxes and Buckingham Palace’ as Dizzee put it on ‘Graftin’’, its music video was shot on top of, around, and beneath the three tower blocks of the Crossways Estate. The estate had been nicknamed ‘the pride of Bow’ when it was built in the 1970s, but bad upkeep of the buildings, untreated poverty and overcrowding meant that the alias did not stick around for long.

The video is shot almost entirely at night time, on grainy analogue film, the Crossways blocks looming over Dizzee’s head, studded with occasional lights. It’s a classic US rap-style ‘hood video’, with Dizzee surrounded by members of Ruff Sqwad, one of the most identifiably ‘Bow’ of crews from grime’s golden age, and assorted other local teenagers. At times he delivers his bars with Canary Wharf’s light blinking in the background. Twice, towards the end of the video, the director splices in a brief, split-second cut-shot of One Canada Square, like a subliminal message – a suggestion that subconsciously, Canary Wharf is always there, when you’re living in and talking about ‘the grime’.11

When vines grow on a hill facing the ocean they pick up the brine on the wind, and the taste of the grapes is suffused with a salty tang. When black British music was pouring, melting hot, into the crucible of a new genre in the early 2000s, New Labour were polling 57 per cent to the Tories’ 25; it was the apex of the blind hubris that led to our current malaise: reckless, wild-west capitalism in Canary Wharf, and New Labour’s carefully controlled vision of modernity and unapologetic social conservatism. This is the tang in the air: tough love, zero tolerance, ever-growing inequality, CCTVs, ASBOs, and an ‘intensely relaxed’ attitude to what was fuelling the economic bubble they said would never burst. In Dizzee Rascal’s first ever interview, he described New Labour’s transformation of the inner city even as it was happening around him. He was only 17 years old in July 2002, sitting on a wall in Bow, with the third of Canary Wharf’s three towers still being finished overhead. ‘There has been bare change around here,’ he observed. ‘It’s all about adapting. Like all the cameras, sly little cameras everywhere, more police, drugs, crime … everything is changing.’12

‘There will be no forgotten people in the Britain I want to build,’ Tony Blair said in a photo call at London’s notorious Aylesbury Estate a month after the 1997 general election, launching the government’s ‘new deal for communities’. British cities were riven by intense geographical inequalities between rich and poor neighbourhoods. New Labour’s concern was that the latter were falling ever further behind the rest. ‘Over the last two decades the gap between these worst estates and the rest of the country has grown. It has left us with a situation that no civilised country should tolerate,’ Blair said in 1998.

Such estates had ‘become no-go zones for some and no-exit zones for others’, according to a government report published that year, which blamed this crisis of bad housing and social exclusion on mistakes by previous governments: in particular, the concentration of the poor and unemployed together in neighbourhoods where hardly anyone had a job. At the time, around 5 million households nationally were in council- or housing-association homes, and the maintenance backlog was upwards of £20 billion. New Labour’s response was to advise councils to seek PFI funding, and to demolish many of the blocks altogether – too many of them were ‘sinking ships’, Blair told the Daily Express:

‘Some estates are beyond rescue and will never be places where people want to live. That could mean moving people to new homes, levelling the site and using the land for something the public wants.’ The idea that the public might want – first and above all – decent, affordable new social housing did not seem to enter into the conversation.

New Labour set up an Urban Task Force, and appointed a Regeneration Tsar, the architect Richard Rogers (aka Lord Rogers, aka Baron Rogers of Riverside – a man with as many alter-egos as a half-decent MC), who delivered a report in 1999 which would shape the future of London: Towards an Urban Renaissance. The report found that one in four people living in urban neighbourhoods thought their area had got worse in recent years, compared with only one in ten who said it had got better; and that unemployment levels in Britain’s inner cities were more than double the national average. The Urban Renaissance strategy proposed to tackle inner-city poverty and ‘sinking ships’ by doing what has now become the norm, and a euphemistic byword for gentrification: they would ‘create neighbourhoods with a mix of tenures and incomes, including opening up council housing to more of the population’. Rogers’ report also called for faster Compulsory Purchase Orders (to get people out of blocks they wanted to demolish), ‘streamlined’ planning procedures, and greater access to PFI funds. Make it easier, make it quicker, and bring in the private sector.13

New Labour promised a ‘lasting urban renaissance’ to ‘stem urban decline’ brought on by the neglect of previous governments. They quoted Tsar Rogers: ‘People make cities but cities make citizens,’ which, like most New Labour slogans, sounded clever without saying anything of substance. The strategy was framed around the goal of arresting and reversing middle-class flight to the suburbs: ‘encouraging people to remain in, and move back into, our major towns and cities’ would be central to the Labour plan, said another report in 2000. These were complex, big government strategies – the Urban Task Force made no fewer than 105 recommendations: one of them was estate renewal, using the private finance initiative. From the outset, New Labour’s plan had been to ‘modernise’ (or indeed, dismantle) the welfare state as it stood, to introduce private finance into everything on the basis that, as the Home Secretary David Blunkett said in 2001, ‘government could never do it all’.

Not everyone was impressed. Two academics at the annual Royal Geographical Society conference called New Labour’s Urban Renaissance strategy a ‘gentrifiers’ charter’. Leading academic expert Loretta Lees agreed, and suggested the strategy might be called ‘the cappuccino cave-in’. The Blairite view was that government had lost control of Britain’s inner cities under Tory rule, who had made urban environments uninviting and unloved.14 Their proposed solution was to encourage the middle classes to move back into the inner city, ‘drawn by a lifestyle where home, work and leisure are interwoven within a single neighbourhood’. Rogers’ report envisioned new middle-class enclaves, populated by people with more time ‘to devote to leisure, culture and education’, wealthier communities that are more mobile and flexible – freer. ‘In the twenty-first century, it is the skilled worker, as well as the global company, who will be footloose. Cities must work hard to attract and retain both.’

Local and national politicians, when they talk about gentrification, often speak of the need to create ‘balanced’ or ‘mixed’ communities. Mixed communities sound good, don’t they? They sound diverse. They sound like they would welcome everyone, and that everyone would benefit from the mixing – by class, by race, by age. No fair-minded liberal would advocate for the opposite: because the opposite is an enclave, or a ghetto. And that’s exactly how – when you push them to reveal themselves – architects of gentrification characterise the inner London that is being rapidly dismantled: a series of social-housing ghettoes, holding back the people living in them – held back not because they are poor, but because they are surrounded by other people who are poor. They’re a bad influence on each other. Bring in the middle classes, and everyone will learn from one another, and thrive. The problem with all this, the deception buried in the rhetoric, is that urban regeneration is almost always a zero-sum game: for some people to ‘come back’ to the inner city, others have to leave.

A decade later, I asked a leading property developer whether building blocks of luxury flats in previously poor inner-city areas was the essence of gentrification. ‘Hopefully we are getting blended communities,’ he replied. ‘In the poor parts of London where we’ve been working in the past, they have been – and I use this term politely – but they have been social enclaves. No one buys homes there, because your money will probably depreciate. But that’s changing. It’s not gentrification, it’s just becoming a more balanced community.’15

In one sense, New Labour and grime should have been allies from the start. The elevation and intermingling of culture and business was integral to the Urban Renaissance strategy: regenerated, modernised cities would be created in part by monetising art and culture. The nature of work was changing faster in London than anywhere else in the country, as the last of the factories disappeared. Following the flag-draped nineties nonsense around ‘Cool Britannia’ that was synonymous with the early years of New Labour, their Cultural Manifesto for the 1997 election was called ‘Create The Future’. ‘Creativity’ became a crucial signifier of Blair’s entire political project, and the New Labour vision of modernity.16 Treating culture as a business connected New Labour to their Thatcherite predecessors, and this ‘creative’ enterprise culture was bound up with urban regeneration, in part by stimulating tourism. As Britain’s de-industrialisation rapidly continued, New Labour was determined to ‘modernise’ everything – from the Labour Party itself, to the NHS, to the workforce, to architecture – and free the party from its electoral reliance on the industrial working class, ‘a class rapidly disappearing into the thin air of the knowledge economy’, as Robert Hewison put it in Cultural Capital.

‘Most of us make our money from thin air,’ wrote Charles Leadbetter, a friend of Mandelson and Blair, capturing the spirit of the times – as music switched from heavy pieces of wax and shiny plastic discs to the intangibles of mp3s, and capitalism moved on from buying physical products with coins and notes to buying and selling complex, abstract ‘financial products’ like collateralised debt obligations, futures and derivatives. By 2007, the character Jez in the sitcom Peep Show would be summing it up in more day-to-day language: ‘I’m a creative. We don’t make steam engines out of pig iron in this country anymore, yeah? We hang out, we fuck around on the PlayStation, we have some Ben & Jerry’s, that’s how everyone makes their money now.’17

But even while New Labour were placing culture and creativity on a pedestal and garlanding it with £50 notes, other government changes were making it harder than ever for working-class people to develop careers out of their creative impulses and talents. In March 1998, changes to unemployment benefits that came in with the New Deal made it much harder for artists to live on the dole while honing and improving their craft – a part of the welfare state that had historically been a lifeline for working-class musicians. The NME ran a cover story about the threat to grassroots music, arts and culture these changes posed, with the banner, ‘Ever get the feeling you’ve been cheated?’ Inside, Jarvis Cocker recounted that, without the dole during the eighties, Pulp never would have made it as far as the nineties, and their vastly better and more popular albums. There were countless other musicians, artists and writers like him. Free education, a strong welfare state and affordable housing had given working-class creativity the space to breathe in the post-war years. For New Labour, it was too much like a hand-out: money for nothing.

The grime kids went without those state subsidies – but still never succumbed to the rampant individualism of their neighbours in Canary Wharf, or their political masters. For all that we should celebrate their independent, DIY spirit and sheer self-motivated perseverance – teenagers with nothing, making something more dazzling and millennial-modern than anyone could ever have imagined – they did so with the help of youth clubs, school teachers, and a collective, communitarian spirit that was being pummelled by a government determined to dismantle it, in the name of remaking the inner city.