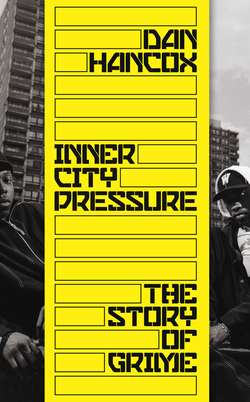

Читать книгу Inner City Pressure: The Story of Grime - Dan Hancox - Страница 19

ОглавлениеFOUR

THE LAST OF THE PIRATES

The first few years of the new millennium were also the end of an era. Grime’s first flush of youth, before it took the name, took place in the last days of a wilder, rougher metropolis; before a swathe of council estate regenerations began and others were demolished altogether. The demographics in areas like Bow, Stratford and Lewisham would grow ever more affluent, as richer people moved in, and New Labour plastered London with CCTV – a change intimately connected to their Urban Renaissance strategy to bring the middle classes back to the inner cities.

Until that point, illegal and semi-legal economies, black markets, cottage industries and thriving sub-cultures circling around inner London were essential to the informal city. In east London in particular, coping strategies in the face of entrenched poverty had long been part of the fabric: ducking and diving, wheeling and dealing, while the proximity to the Thames and docks meant historically the black market was always thriving.1 There is very little left of the informal city now, and pirate radio in the grime era might be the last bastion of truly autonomous, urban working-class self-expression – autonomous in the sense that it is possible to make a living from it, without the approval, or profit extraction, of the whiter, wealthier established British culture industries.

Mostly, it wasn’t about making money at all. In fact, DJs would pay monthly ‘subs’ of £20 or £25 for the upkeep of their station, and broadcast to a narrow radius of only a few miles, for the sheer love of it – although, in return for their subs, equipment and dubplates, came rave bookings, record sales, and a just-about-sustainable living. It’s hard to overstate how vital the pirates have been to the incubation and growth of eighties and nineties dance genres, from acid house and soul through ragga, jungle, happy hardcore, dubstep, UK garage, bassline, funky house, and so much else of the UK dance family tree. Their proliferation had reached a high point by the early 2000s, and they were the lifeblood of grime in its embryonic period: a meeting point; a testing and rehearsal ground for new and established talent, live on the mic and on the decks; a place where hits and stars were made; a communication channel and a binding agent, for the community contained within earshot. ‘I came from nothing. I came from the underground, the pirate-radio scene,’ Dizzee Rascal said in his Mercury Prize acceptance speech in 2003. ‘If you don’t acknowledge it, it will creep up anyway.’