Читать книгу Lighting Out - Daniel Duane - Страница 16

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

9

ОглавлениеEpic: ep-ic\’ep-ik\ adjective [L epicus, fr. Gk epikos, fr. epos word, speech, poem] 1: of, relating to, or having the characteristics of an epic. 2a: extending beyond the usual or ordinary especially in size or scope. b: heroic. Noun. 1: a long narrative poem in elevated style recounting the deeds of a legendary or historical hero (the Iliad and the Odyssey are epics). 2: a work of art (as a novel or drama) that resembles or suggests an epic. 3: a series of events or body of legend or tradition thought to perform the proper subject of an epic (the winning of the West was a great American epic).And now, verb—“to epic.”

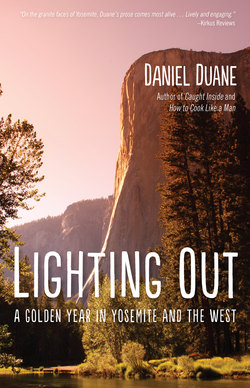

Nick’s feet fell hard off the dashboard. He sputtered “Oh, God . . . me,” rolled down his window, and climbed out. First his head, then his arms, then his whole upper body was out of the vehicle with his Birkenstocks kicking around near the stick shift. I looked back at the road. Beyond a broad meadow, above a line of trees, something a mile away filled the windshield. A wall. A big, big wall. I leaned forward to look up. It still filled the windshield; I got my neck over the steering wheel and still I couldn’t lean far enough to see the top.

I hit the brakes and Nick grabbed the windowsill to keep from falling out altogether. We opened our doors simultaneously, turned off the radio and stood barefoot in the gravel. Three thousand feet high and a mile long. And vertical. Twice the height of the World Trade Center and much, much cleaner of line. Higher than safe cruising altitude for skydiving. More than half a vertical mile. Swirls of bright white-and-gold granite the size of towering thunderheads in the sun. We stood next to the truck and I felt my palms moisten. I wiped them off on my pants without looking away, but they kept sweating.

Nick walked forward a few steps in the gravel, took a step left, gestured helplessly with his hands, then looked back at me. “El Cap, huh?” he said.

“Mmm.”

“Fuck that, eh?”

It did look pretty frightening, the thought of trying to get up on that monster. We drove on into Yosemite, slowly, both our heads out the windows of the truck. The valley rose wildly to glacial headwalls—the flatiron of Sentinel Rock, Yosemite Falls spraying into a thousand feet of air, and the crown jewel looming over the far end of the valley—Half Dome. A mountain of forest and stone lifted its rounded two-thousand-foot face far up over placid Mirror Lake, pushing the summit to nearly five thousand feet over the valley floor. Dad and Sean had taken a day longer than they’d planned and looked pretty bad when they got home. They both felt that El Cap—the ultimate rock climb—was beyond them. The whole scene felt beyond me.

We unloaded at the climbers’ camp—officially called Sunnyside Walk-In—unofficially Camp 4, after a cramped sleeping ledge high on El Capitan. Tents from all over the world crowded together on pine needles beneath sequoias. Picnic tables were strewn with beer bottles, jars of salsa, half-empty cans of beans and bags of cookies. In front of nearly every tent was a pile of great-looking equipment, of ropes, hammers, Friends. On the bulletin board at the ranger’s kiosk were notes scrawled on torn scraps of paper: “climbing partner needed, I lead 5.10, follow 5.11,” “Partner needed for Zodiac, must have PortaLedge and jugs,” “Swiss girl needs ride to Modesto,” “If I had a car I’d give you a ride,” “I have a beard, and I’ll give you a ride.”

With Nick’s little blue tent pitched, we sat out in the morning sun on the tailgate of the truck and sorted gear. Everywhere were climbers, bullshitting the morning away, happily exhausted, some probably just down from days on a ledge. Young European men—tan, unshaven, filthy and wearing filthy clothes—cooked coffee on little aluminum backpacking stoves next to their obligatory enormous American jalopies; men who’d lit out for a year, were taking time off. All over the lot were dusty old VW busses, outfitted with elaborate cabinets and beds, plastered with bumper stickers and window transparencies of stars, rainbows and the earth, of dancing acid bears and “Free Leonard Peltier.” On the back of an old Ford van, a pharmacy’s bumper sticker had been appropriated: “Wall Drug.”

Nick and I got to work—he cooked up coffee while I organized the rack of protection the way Dad had shown me. When the coffee was ready we both shoved our hands in our Patagonia jacket pockets and unconsciously tried to look worn out, like we’d almost killed ourselves the day before and needed a break. The sun over Half Dome branched down through the pines in broad, dusty rays. That these men were here at all, particularly the Europeans, the South Americans, the Japanese, meant they were in the midst of a lifetime dream—climbing in Yosemite Valley, in California, in America. World famous rock walls—El Capitan, Half Dome, Sentinel Rock, the Cathedral Group—some of the most compact, solid granite on earth.

While we nonchalantly laid our own gear out on the tailgate, we caught glimpses of guys’ hands as they walked by: climbers’ hands—swollen, coarse, soiled, covered with scabs from being shoved into cracks—real hands like my dad’s, hands wrapped in white athletic tape as armor for the day’s struggle. Two climbers who stood eating granola from tin cups were so lean and sunburned they looked wolfish and undernourished. Definitely not studying postmodernism at Yale. They had adaptive body-types, wiry, tight and hard. My own hands seemed soft and intact.

Nick practiced coiling our new ropes on the ground. Embarrassingly clean, they were bright yellow with snake patterns of red and blue. Dad didn’t mind my using his rack of chocks and Friends, but ropes were taboo. You never lent out ropes. Because they were kernmantles, with an elastic core sheathed in woven nylon, the core could be damaged without visible sign. The carabiners—aluminum ovals that fit perfectly between fingers and palm—each got an affectionate snap with the thumb; just practicing, getting a feel for them. Nick pulled the triggers on the Friends, added a little silicone dry-lube.

“Gears a little stiff?” I asked.

“Yeah,” he said, from the back of his throat. “Little stiff.”

He bit his upper lip and tried to look fierce as he thrust a Friend into the joint of my camper shell’s door—pretending it was an overhead crack. Two tan, dreadlocked white guys kicked around a footbag in a patch of sunlight. They both had climbers’ hands and sun-bleached beards. One had scratches across his chest and back and was so gaunt he’d tied his tattered canvas pants up with a string. His muscles flickered under his skin like woven piano wire. They kept the little leather bag in the air: warming up, talking about whether they should go down to the Cookie Cliff and try Butterfingers.

I grabbed our copy of the Yosemite Climbs guidebook. The Cookie . . . Butterfingers . . . 5.11c. 5.11c! On a difficulty scale from 5.0 to 5.14, where 5.0 is virtually a steep staircase and 5.14 is an overhanging Teflon-coated mirror, 5.10 even seemed so thin as to be almost unclimbable. But 5.11c? And they couldn’t have been much older than us . . . in fact a sharpeyed blond kid looked younger. My dad still hadn’t led anything harder than 5.10. Climbing at that level had to be some kind of near-mystical dance, way out west, way up on walls. The picture of Butterfingers in the book looked like a perfect crack on a smooth, dead vertical wall. It looked like fingertips would fit inside, but not well.

On a broad green tarp by a camouflaged van a short, skinny guy with a long handlebar mustache and ponytail had spread out more gear than I’d ever seen. Nick poured us each another cup of coffee. Then he started putting our gear into our bright new packs while I snuck a few glances—a monstrous white bag stood off to the short guy’s side, and I was sure it meant something. Although empty, it stood upright, about three feet high and cylindrical. Heavy nylon flatcord—or webbing—had been sewn down two sides, under the bottom and up again, forming thick loops above the open top of the bag.

Then it struck me—a haul bag. A real, Fish-brand haul bag. The genuine article like Dad and Sean must have used on Half Dome. I’d seen pictures of them, and knew they were the only bags durable enough for hauling food and supplies up the great walls on multi-day climbs. Fish was rumored to have tested them by tying them to the back of his motorcycle and driving out on highways for hours at a time. This man was preparing for a big wall—a Big Wall—Half Dome, maybe even El Capitan, “The Captain,” sleeping on ledges thousands of feet off the ground, doing nothing but climbing from dawn until dark, popping open a can of cold beans for dinner and having it taste better than any steak on the ground. A psychotic divorce from the world, requiring clarity of mind through long periods of terrifying quiet. My father had many books about Big Walls, photographs from his recent Half Dome climb.

Iron spikes called pitons were spread out all around the hero. Twenty or thirty soda bottles wrapped in duct tape stood empty against the red van—water for a week. I couldn’t believe it. I had to stare, look at him closely, try to get some hint of how he could be so calm on the docks before sailing. His hands were already taped. It seemed such a bizarre aspiration, such an insane way to spend one’s time without even the comfort of a beer in the meadow at day’s end.

A strung-out redhead sat on the ground next to the Big Wall astronaut. He was tense and big-jawed. His wiry hair stuck out on all sides while he chattered away. He had his own pile of equipment.

“All for sale,” he said to us, smiling with brown teeth, “all of it. Forty-three carabiners, a full free-climbing rack, ropes, slings, a few bugaboo pitons and five or six copperheads. Getting out of climbing.”

“Why?”

“My buddy was fully soloing the DNB, like a few days ago, and I was watching him through the binocs when one of his hands just popped off, like a hold broke or something.” He pursed his peeling lips and shook his head. “And I seriously saw him falling. I ran to the base of the cliff and his ankles were up in his hips. I freaked and jammed off for the medics. Those Friends are going for twenty bucks each.”