Читать книгу Lighting Out - Daniel Duane - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

1

ОглавлениеOn my last day before flying back out west, I had a final beer with the campus literary journal. A cold spring rain washed the windows of the old Albatross Pub as we toasted our fiction editor’s acceptance to grad school at Yale. Post-Marxism, postmodernism—Drew was on his way. At an oak table under an autographed oar he told us about the honors thesis that got him in—political repression and human anatomy in two early British novels. Obscene and fascinating, it had been an unplowed field. Greek letters carved in the tabletop lay preserved beneath a coat of polyurethane; old photographs on the walls of pale rowing crews and muddy football teams were strictly black and white. Both California graduate schools I’d applied to had just axed me; two paper-thin envelopes had arrived together.

“Why only West Coast schools?” asked a diminutive and anxious grad student from India. He’d just dropped out and supported himself by handing out the Workers Vanguard and ghost-writing essays—eighty bucks for an A, sixty for a B. I filled my cheeks with Ivy Stout and thought over how to answer without exposing my less-than-total commitment to the life of the mind, my flakiness. I just wanted to get away from angst-ridden winters and state parks the size of football fields. After I’d quit the fraternity, college had certainly improved—our journal had made a splash when Drew used margin text to create resonances between eco-feminism and fascism—but now I wanted to go home.

“I mean,” Drew demanded, “you did only apply to West Coast schools, right?”

Grad school back East? My twenties in Providence? New Haven? Princeton? Baltimore? These were dying cities, but how to say to people who forgave my fraternity sins that I needed to live near mountains more than a few thousand feet high? And without farms and turkey hunters in them? So I swallowed my beer and said offhandedly that I just liked it better out there. Things were just, I don’t know, more beautiful. Wide open spaces, and all that. The whole western world out of sight behind you if you wanted it there. And what a dump upstate New York seemed that afternoon—drizzling and cold in May; muddy, owned, farmed, crowded, fenced-off. Even after four years I couldn’t get rolling hills and Appalachian villages to feel like home. And that morning my type-A girlfriend, a carnivorously intellectual sorority girl, had dumped me in the name of practicality—different coasts, different dreams. I had an airline ticket for the next morning, skipping graduation.

“I’ve been to California,” Drew said. His head so outscaled the rest of his body that the whole black-turtlenecked arrangement tottered forward under the weight of his ivory jaw. “Yeah, my freshman-year roommate’s place in Marin County. One of these BMW Deadheads with serious wealth in the woods and constant fresh-squeezed OJ. No poor people anywhere.”

The gaunt poetry editor smirked and fingered his ponytail. Visions of Vineland, of hot-tubbing Aquarians—indelible and unassailable; I’d put some of these ideas in their heads with my talk of hot springs in the high mountains and pot plantations in redwood country. Places I wanted to get back to, or hadn’t had enough of in the first place. A nativity I’d never fully acquired. The art editor, son of New York rural hippies, enormously muscular and wearing old army pants and a Tibetan vest, looked hopefully at me for a rebuttal. My vision of California had appealed to him, maybe a place to go after school. I looked out the window to where his battered blue-plaid VW bus was parked in the rain.

“Guy insisted on hiking clear to the top of Mount Tamalpais every night,” Drew continued. “Pretty smashing sunsets looking way out to sea, and it’s supposed to be some great power spot.” Drew waved around a cigarette as he spoke, dropping ashes on the table and staining his slender fingers yellow. “He swore some beatnik poets went out there in the late fifties and marched around blowing on conch shells and chanting sutras or mantras or something, so locals think the place is sacred.” I coughed a little from the smoke as my own version of Mount Tam came to mind—from Berkeley, it was a black-etched peak north of the Golden Gate lit by a burning aura from a late summer sunset. “After a week out there,” Drew said, “I was changing into somebody I didn’t want to be.”

The debate was my fault to begin with—playing the stage Californian when I’d failed at being Ivy League. The poetry editor looked evenly at Drew and me, weighing. A charismatic and emaciated neo-Marxist with a penchant for the occult, he’d grown up in Toronto and spent his summers acting in London. He loathed Ithaca’s provincialism and preferred the darkness of European cities—“shit” was happening there, changing, cops with submachine guns hung out at street corners. Sure, he’d been to a few sweat lodges with the local Black Turtle Indian Nation, but four years of hearing from me about the nature/culture split and the pristine beaches of Point Reyes had eroded his sympathy. I think my girlfriend had felt the same.

So I said I knew people in California who went to work every day and came home and paid bills and made love and got pissed at each other and it all seemed pretty real last time I was home. “It’s just that when you’re in a lovely place,” I insisted, knowing it sounded ridiculous to the whole editorial board, “it changes how you think. Maybe just a little bit, but it does. Like photo-deprivation depression. Or old doctors sending you to the south of France for cures.”

The sutras on Mount Tam even sounded all right to me—we’re a young culture, got to start sacralizing somewhere. My own honors thesis had been on the poetry of nature and place, some of it deliciously misanthropic. I’d been looking west, had ignored all the relevant scholarship and followed the advice of an old professor: “Just say no to theory.” They gave me lowest honors. Drew’s critique of the dispersed exercise of power had gotten him a summa.

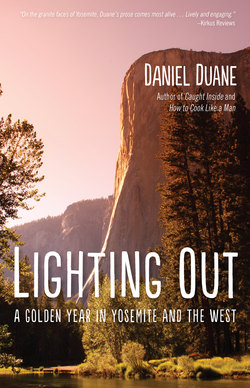

“And anyway,” I said, “there’s stuff I want to do out there before I get on the career track, like learn to climb.”

“Climb?” Drew asked.

“Yeah. Rock climb. My dad’s into it.”

Drew took a long drink from his ceramic stein, then wiped his lips and smiled.

“The old WASP nostalgia for culture-free wilderness,” he said, winking at the poetry editor.