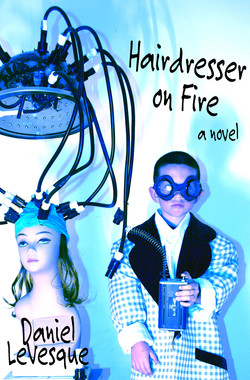

Читать книгу Hairdresser on Fire - Daniel LeVesque - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеMy sister wanted contact lenses more than I wanted Clown White. Going into ninth grade, she was as marked as I was. I can’t imagine being a girl in ninth grade, let alone being The Girl in The Cult, the one with the big nose and glasses. My father felt bad for not being able to provide contact lenses, and for passing down the giant schnozz that they would bookend.

He saved up all his working-class nickels until he could afford the new eyeball covers she wanted. He was proud when she opened the package and saw them; I think we all cried. My family was always happy for one another when something went well. Not a lot of competition when the bar is so low. Not particularly encouraged, I never shot too high, something that is with me to this day.

When I wanted a paper route my mother said, “Oh, no way. I am not driving around in the rain at seven in the morning on Saturdays when you don’t wanna wake up and do it. It’s a big responsibility, Francis. You’ll join up and then you won’t do it, just like the Cub Scouts. Remember the Cub Scouts?”

When my sister got to remove her giant glasses, I was genuinely happy that she broke through to my parents. To her, they didn’t say, “Oh, we’ll get ’em for you even though you probably won’t put them in.” They just got them for her, knowing. And she wore them, too. Every day. Her old glasses sat on her cracked wooden shelf like a fossil; on one lens was a gold butterfly and on the other lens were her initials. They were that big.

When Wilton and the other Men in The Community found out about the contacts, they called my parents into an emergency meeting with the parish priest, Father Moe. Moe was a raging queen who was later sent away from the Church — not because he was diddling boys but because he was having sex with men, and because they knew he was a big old ’mo. Father ’Mo.

“So, Wilton, what’s this all about?” my father said.

“Maybe we should all sit,” said Father ’Mo.

“Yes, maybe. Good idea, Moe,” said Wilton.

My mom sat silent as Wilton took the seat across from my dad, took Father Mo’s seat. Wilton was such a fucking donkey.

“We see you bought your Carlene some contact lenses… that’s what we heard from the girls today, that Carlene had some contacts in at school.”

“Yeah?” my father said.

“Well, we just don’t think…”

My father’s hands shook as he waited for Wilton to say it.

“…we just don’t think you should be making such large purchases without consulting the Community first… or at least tell Moe here…”

“Father Moe,” said Father ’Mo.

“Father Moe… sorry… but we — me and Moe — see this purchase as a reduction of your tithe, of our tithe, and we can’t have that. You understand.”

My father jumped out of his seat and held up his hand to the men with his middle finger extended. He never did it before, maybe once in the Navy, but giving the finger wasn’t his long suit. Like me, when enraged, he turns into Don Knotts.

“Screw you, Wilton!” he screamed. “Screeew youuu!” His voice shook into the higher octaves, his register getting tighter with each word and his voice cracking. “I’ll buy anything for my damn kids that I damn well want. You don’t tell me how to spend my damn money, you big jerk!”

My father grabbed my mom and plucked her out of her seat — she was starting to cry — and pulled her out of the room, pushing past Wilton and through the door, walking out the clackety doors of the church rectory. “And screw you too, Moe!”

And that was it. As fast as we were in a cult, we were out. No deprogramming required. My parents got into their Impala and drove away.

“Well, that didn’t go as well as I had hoped,” said Wilton. “I guess some folks just can’t be saved, huh, Moe?”

“Father Moe,” said Father ’Mo.

I was pretty lucky that I never had to come out. It was already done for me, evidenced by my wig box and assorted props: cheerleading pom-poms, juggling bags, eye shadow sponges, and yarn. Nobody had to tell anybody anything. Trust: when your nine-year-old’s “down time” fills itself with walking serpentinely through the house in a blonde bouffant wig and digging through your dresser for Maybelline eye pencils, you don’t need to do the math. Equation solved. Marty Pagan’s toy box lay in sharp contrast to mine. He had not an old wooden toy box but a new one in the shape of a giant NFL football, the smell of thick plastic surrounded it from a solid foot on each side. It had its own aura. This giant toxic football like an advertisement, stuffed with tennis balls, catcher’s mitts, and the hand-held sports games that bugged me with their constant squawking for touchdowns or more batteries. Above the sports slush and the electronic games screaming feed me hung every baseball card ever printed, screwed to the wall on display.

Above my wig box — the wooden crate that was a tangle of synthetic hair — hung no such paraphernalia. Other than my KISS posters, I didn’t hang much. There was a personalized letter from Leo Buscaglia, whom I’d written to after reading his book, Love. A picture of me with The King at a Medieval Times in Florida — the King just looked like a dude from Orlando, not particularly enraged by his job. I looked by far more uncomfortable in my Vacation Costume posing with a character actor in a theme restaurant.

Next to that was a picture of me posing with Willie Whistle, the local clown of my youth, at a senior citizens facility outside Boston. I have no idea how I even got there. Driving to Boston was always a hassle for my parents and we rarely did it. We barely even crossed into the Massachusetts border towns that surrounded us in fear of The Massholes, or as we called them, The Hillbillies. Rushing home from third grade to make sure I caught my stories — General Hospital was gearing up for the Ice Princess and big things were happening — I’d see the other kids planning their afternoons. Shooting hoops, skateboarding, and eventually, thank god, playing Atari. I sat myself in front of the full-length mirror in my mother’s room. She was ironing, singing a Mama’s and Papa’s tune as I patty-caked against the mirror.

Having nobody to practice with, my stoned sister proving no help time after time, I depended upon myself to learn the hand-clapping routine. The order in which to clap, pat, cross your hands, or slap your knees was critical business in the schoolyard, at least among the circle of girls I watched at recess. I wanted in. As my only competition I got wicked fast real quick and before I knew it I was a blur of arms in front of the mirror.

… old lady mac, mac, mac

Marty Pagan was coming up the driveway, I could hear him dragging some piece of metal sports equipment. I knew he was going to bother me so I picked up the pace of my clapping, patting, and crossing, dropping the total hint. Ignorant, he came to my mom’s window.

“Hey, do ya wanna come play baseball with us?”

…all dressed in black black black

“Shhhhhhh!” I said. Clearly, the rhyme wasn’t over. He was bothering me in the middle.

…with silver buttons buttons buttons

“Hey, Francis, you wanna come play baseball?” he repeated. They must have needed someone bad. My concentration was broken and I was getting flustered.

“Can’t you see I’m busy? What’s wrong with you?” I said in the mirror, his stupid half-head in the window. I started my hand claps again, from the top.

…old lady mac, mac mac

“Why don’t you wanna play baseball?” Marty was incredulous, outside the window, standing on my baton with his stupid sneaker.

…allll dressed in black, black, black

I got louder. I wanted to take that bat to his head and really swing. He was bugging me now.

“And why are you always practicing those girl games?” he said.

…with silver buttons buttons buttons

Before I could jump up and run outside, my mother slammed her iron down onto its board, mashing the steam on button, leaving spurts of hot water and tea-kettle clouds blasting behind her as she marched to the window. Her little body could really move when she was pissed, and she looked like she was going to rip Marty in two.

“He’s good at it. That’s why he practices, Marty, because he’s good at it… now move your feet outta here… do what you’re good at and go play your baseball, you little shit.”

…all down her back back back

Marty looked at my mom and ran away, schooled.

“He’s a little shit,” she said. “You’re good at it. Keep going, hon…” My mother was free and happy outside of the cult, ready to pick battles and say “shit” outside the house.

She started singing again and my hands regained their speed, challenging their own reflection. My mom was right. I was good at it and I would patty-cake, satisfied, until I could move on to public transit and bigger towns.