Читать книгу Hairdresser on Fire - Daniel LeVesque - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

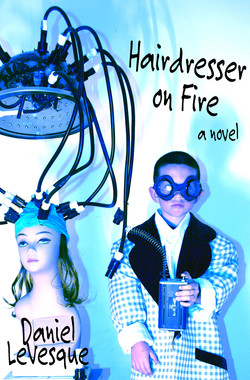

ОглавлениеDespite what has been written on countless salon applications, I cannot say with any stitch of truth that my childhood dream was to express myself through hairstyling. It’s all a lie. There was never any burning desire to do hair — not to touch it, arrange it, or place adjectives in front of it, e.g., overprocessed or silky hair.

If you ask, you’ll often hear the story told in a mystical way. Ramón will tell you, “I was doing hair in all of my lifetimes,” spinning his hand above his head, a halo of tracers orbiting his hairdo, opal black eyes turned skyward (trust I am not poking fun at the Ramóns of the world. I adore the Ramóns; without the Ramóns, I am nothing). But, unlike The Ramóns, hair was not my calling in grade school, and falling into it was nothing more than random cosmic career assignment. I could just as well be repairing people’s air conditioners today, or drawing their blood. Massaging their thighs. A Trade. The sun eats itself.

At eleven years old, my Grand Purpose, my calling, was to be a circus clown and a stuntman, merging the two into one glamorous pratfalling career. Dick Van Dyke tried it but not on the scale that I’d envisioned.

My father loved The Dick Van Dyke Show. In the opening, Dick would walk in and trip over this hassock, and every time my dad would crack up like he never saw it coming. He’d laugh so hard that no noise came out, lying on his belly in front of the teevee with me sprawled over his back like a little monkey. When he’d laugh so hard he was like a ride at the fair, his back heaving silent screams of laughter, me flopping back and forth until I cracked up too. I always found comfort in the laughter of my father. For me, it wasn’t about the hassock at all.

After a few seasons of the show, the opening changed. Dick Van Dyke would come in, act like he was going to trip over the hassock, and then do a near miss, jump-over-the-hassock gag. Upon landing, there was this little steppy tap dance number he did, mincing and grinning real proud. The clever side of the Fool. My father didn’t laugh at the beginning anymore so he would get up, tossing me into the deep shag, and change the channel. He liked that hassock bit a lot. He sure did miss it. This would not be the summer that my father got sober. Thanks a bunch, Dick.

Other than wanting to slam Dick Van Dyke’s long face into the cement wall of our cellar, I wanted clown props, and would have traded all the giant honking horns in the world for a set of clown make-up. Becoming a clown without proper make-up is difficult at best, a possible reason for so much sadness and alcoholism present in the clown community: Repressed Childhood Make-Up Memories. No mother wants their son to love clowns, let alone be one.

As Clown Children we are marked, and for this we are forced to dig, to find a way to make it happen. Unlike the way Theater People start out — jazzy adolescents in Drama Club, scrawling loopy “See ya on Broadways!!!” in senior yearbooks — Child Clowns have no such reception. We must learn early to make our childhoods work or to break them ourselves. Nobody reaches out to help a kid who wears suspenders so we chew holes in the box.

In lieu of owning a tube of Clown White, I used a lotion/talcum powder recipe. Oh, coveted Clown White, with your perfect consistency and shocking opacity. I could eat you, the way I eat my sister’s cherry-flavored Bonne Bell lip gloss. I need you. I never get you.

My mother’s top dresser drawer only collected things I couldn’t use for painting my face. Ketchup packets from Burger Chef, single use salts and peppers, old samples of beauty products that she would never consider putting on her face or throwing away, empty matchbooks — these are the items she hung on to.

Medium-brown Maybelline stick was the only make-up option among the riffraff that filled my mother’s dresser. I used it for lips, eyes, and teardrops. The lack of rouge pushed me dangerously close to mime territory so I did what I could with what I had. How To:

1) Begin by applying a light layer of Mary Kay lotion over the entire face.

2) Wait until it almost stops stinging.

3) Pat mounds of talcum over the sticky lotion.

4) Drag the scratchy Maybelline medium-brown pencil around eyes and lips until skin tears and bleeds, creating a total look.

Results were most often clumpy but after a few applications a sufficient washed-out pallor would take over my face, flaking like oats within an hour as I jumped off the garage in the summertime for stuntman practice. A ruby red lipstick was my only saving grace and I used it sparingly, saving it for serious clown shows or when pictures would be taken. It was a full tube but I knew better than to waste it. If I had to name the color, it would be “Mercy.” The tube came from the house next door where I could sometimes get lucky, hoping my neighbor would toss me a lipstick she didn’t like during spring cleaning.

“Take this one, hon. It’s Mary Kay SHIT,” Betsy would say. She was allergic to Mary Kay, as was my mother. But my mother didn’t have any lipsticks hanging around, just the ketchups. Betsy had so many lipsticks she didn’t use anymore, all reds. I would have run away to next-door for the simple promise of a discarded lipstick once in a while, maybe some proper concealer. I always wanted to live with our neighbors, the Pagans, right next door and a thousand miles away. Bobby, Betsy, Marty, and Jennifer. The Pagans.

Bobby Pagan watched a lot of teevee and stuff — it was always on for some sports show — but their house had a different feeling, a different smell: the smell of burning electricity from the all the teevees running in empty rooms, the smell of ovens preheating and cold cardboard under frozen pizza. The Pagans didn’t hide their empty wine bottles or wash the red rings of cheap Port from the bottoms of their glasses before going to bed. The Pagans fought and didn’t make up, they went to bed mad. The Pagans said fuck.

I tried to be there as much as I could, as Betsy Pagan had all the best clown shades in her make-up box but, God, if she caught me in her room without permission she would throw a bottle at my head. Betsy collected bottles, always having a head-smasher within arm’s reach. She would grab for the heaviest bottle, the one with all the quarters in it, to whip at my head. It must have had a hundred bucks in it. Don’t think I wasn’t eyeballing that one, either. Its coins could have bought my bus ticket to clown school and back. It was one of those wine bottles from Italy, wrapped in its own wicker basket by children with nubby fingers. You could hang it up.

There were bottles with wax dripped down them in colorful layers, years of flaming candles formed into mounds, the wax so thick on some of them that there was only a hint of the original bottle’s shape left behind. Some of the bottles had shells in them. Shells and sea glass stomped into pieces so Betsy could cram them down the neck of the bottle. My mom said that Betsy only filled all those bottles because she had so much fun emptying them. A lot of the time my mom breaks her own “if you can’t say anything nice…” rule. Sometimes you have to.

Betsy would spend hours ripping up tiny pieces of masking tape and sticking them to the emptied Blue Nun bottles, until every inch of glass was covered for all the tape. Magical faux finishes appeared when she began rubbing over the tape with shoe polish on a paper towel. It created this cracked brown look over the surface, dark in some places, lighter in others, and I must admit that even I was a little taken aback by the results.

“Betsy, I love that one over there. The one with the dark brown shoe polish all on the tape.”

“It’s sable brown,” she’d say. “The shoe polish. Sable. Like my hair.” Betsy’s hair was flat-tire black, nothing at all like the chocolaty brown shoe polish shining off the bottle in the corner. She acted like she invented it, too, this whole tape and shoe polish process, not wanting to share her medium with the world. Activities such as tape-rubbing are supposed to make old people happy, or give schoolchildren something accessible to create. When crafts are elevated and held to any sort of standards, the whole world suffers (witness the bonsai community).

Betsy would soon be involved in macramé, a then emerging form involving knotting pieces of twine into patterns. Once she was convinced that her style of knotting twine was exclusive to her, Betsy began fashioning macramé bottle holders. It was the next logical evolution of her talents, creating new places to put new bottles. Once a year she sold the completed pieces at BraätFest, a local French-Canadian church bazaar with a dubious Germanic moniker.

The artisans who rented BraätFest booths sold an assortment of crocheted toilet paper cozies, shouting wooden WELCOME! signs, potpourri baskets and — for the first time this year — macramé art. Betsy sold the most with her bottle holders. Seems a lot of people at church needed a place to put their empty bottles and dressing them up in waxy twine was the perfect idea.

My mother never attended a church bazaar on principle but would always volunteer to clean up after. She would be furious, scratching at a piece of scotch tape stuck to the nose of a statue of Saint Agatha. “Jesus smashed the temple in Jesus Christ Superstar because people were making money in God’s house, remember? All those girls were dancing, remember? And the drugs and the guns and the mirrors! All in His Father’s house! Jesus was so mad, so mad He smashed the mirrors!”

Everything I believe about Christianity is from the movie Jesus Christ Superstar; it’s a good reference point.

“Jesus said, ‘Not in my Father’s house, you don’t! No way, José!’ and Jesus flipped those tables and yelled at those vendors, ‘Get out! Get ouuuut!’ he says. Remember? Same thing with the bingo. And these goddamn church bazaars.” She looked around when she said goddamn to see if anyone witnessed her breaking the third commandment.

Blasphemy is big in my family of devout Catholics, especially the older ones. They took these phrases with them from Canada, these insane combinations of words. Phrases that reached the height of irreverence, these little Canuck sacrileges that flew out of my grandmother’s mouth. “Eee, Mutarde si marde Tabernak,” “Ah, siboire,” and “Ett, Crisse,” were spoken from the safety of her La-Z-Boy without fear of heavenly repercussion.

I didn’t know what the words meant as a kid but, roughly translated, Memere and Ma Tantes were saying things like “Mustard shits on the tabernacle,” and “Shit on the Holy Host!” with zero regard for the third or fourth commandments. My parents said “Mutard si merde,” and “Ah, siboire,” all the time and when I would ask what the words meant they would tell me, “It means ‘mustard seeds.’ But don’t say it.” To this day, I don’t say mustard seeds.

My mother was kneeling at Saint Agatha’s feet with a dust rag, wiping between the cemented folds of her hem. “Eee mutard si merde. Jesus would flip these tables if He knew what was going on in here… but He knows. Oh, Heeee knows… People playing roulette in the house of God. Gambling!” She was right. I wanted to flip the stupid tables myself. It was all so bright and finicky, covered by the smell of church basement coffee percolators being emptied, their insides scrubbed with church basement cleaning liquid and steel wool.

“And Betsy Pagan! Oh, I’m sure she’s gonna give ten percent back to the church with her stupid bottles, I mean, who couldn’t do that? I could do that! Wax on bottles? Stupid. And it only gets everywhere, see? Look… look… I mean, it got all over Saint Agatha’s basement floor, that’s all I know. Goddam bottles.” She looked up to the eyes of the statue, little home-permed curls pressed in sweaty rings around her forehead. “Oh, Saint Agatha, as if you didn’t have to see enough suffering already,” she said, crossing herself once before standing, then again right after. “They cut her tits off, ya know.”

My mother didn’t know about Betsy’s macramé bottle holders yet, and I wasn’t going to be the one to tell her. She was convinced that the Pagans were up to something at all times because they didn’t have a crucifix hanging in their house or a picture of a lamb or anything. Just the bottles. “And that lipstick!” my mother would say, and I would always know the exact shade Betsy had on that day. “That lipstick! S-L-U-T R-E-D, that’s the shade.”

The same Slut Red I dreamed of stealing, to stain a smile onto the inch of skin surrounding my mouth, allowing for entrance to the school of my dreams. I will get in, I thought every day as I waited for the mailman to come with my information packet.

The application form for the Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Clown College is the same form used for evaluating patients before admitting them to psychiatric hospitals.

The written evaluation begins innocently enough, lulling you into a clown-ready state, a rubber-nosed frenzy of fantasy and longing, before they slam you with the hard questions. (There must be some sort of practical exam done later, after you’ve wowed them with your credentials on paper.)

The full-color catalog of classes they sent had course titles that damn near killed me from anxiety. Intro to Pratfalling with Professor Stumbly. Advanced Team Juggling with Miss Scorchy. Stilting 101 with Clementine Shorty. Judging by the pictures, student clowns went everywhere on stilts, bright smiles beaming through painted frowns.

Their make-up was high quality product expertly applied and I would’ve killed them for it given the chance. Glossy candid shots exposed the student clowns in their off time: combing their wigs, drinking out of cans, stilting around with red rubber balls that swirled in the background of every picture. In their breakfast photo they were eating noodles; I wanted to join them immediately.

After licking the pen tip real hard, I started filling out the application for my life.

NAME: Francis Stewart Plinkin/Zilcho the Clown — I wasn’t sure if they needed my real name or my clown name, so I put both.

AGE: 18 — I put eighteen instead of eleven. I didn’t want to scare them off with my youth before I had the chance to win them over in person. Age wasn’t a worry, as Institutions of Higher Learning were beginning to appreciate the genius of youth. All over the news, on teevee, on That’s Incredible!, there were eleven-year-olds in post-graduate schools, preteen geniuses performing microsurgery and shattering ageist constructs, but these were the rich kids at Johns Hopkins Medical. Clown colleges most likely had a different take on early entry programs for geniuses. I licked the tip of the pen again, something I saw my dad do, and got serious. I didn’t even put on a full costume.

HOW MANY TIMES HAVE YOU MOVED IN THE LAST 10 YEARS? — There was the once, out of the project and two streets over to the tenement but I didn’t remember it. “Six times,” I wrote in my best handwriting. Logically, they would be seeking someone driven, with a penchant for travel, not some dead weight balloon-twister who’d be content to work the local birthday party circuit for the rest of his life. “Six times” should properly amaze the admissions clowns without going over the top.

HOW MANY JOBS HAVE YOU HELD IN THE PAST 10 YEARS? — “Six.” Obvious. I was on a roll. Willing to work. After a few more questions about the basics — location, gender, citizenship — I moved on to the next section where the innocence wore clean off.

The psycho-social part of the application was a mind-boggling collection of questions pertaining to abuse, buggery, IV drug use, and prison records. I laid myself on the floor, pressing my cheek to the shag until composure took me back to a place of readiness.

Marty Pagan and his friends were playing outside, giggling and chatting as I sat with my application. They were talking about me. Bottomfeeders. See what they say about me in six months when I’m famous and they’re going nowhere. So what if I can’t play hockey? Those helmets give me a headache and I don’t see any of them applying to colleges. Okay, focus. The pen was sweating in my hand and I was craving make-up.

HAVE YOU BEEN CONVICTED OF A FELONY IN THE LAST 10 YEARS? — “No.” Bonnie Beleau forced me to steal bath beads from Mammoth Mart once but I got away with it so I’m sure there’s no record. It was all Bonnie’s idea. She practically stuck them down my pants. Before I knew it, I was shoplifting, Bonnie going “Come on, come on,” the whole time and me, guilty as hell — I was sure they’d catch me — flushed and anxious as I passed the giant elephant who guarded the door. We popped the bath beads with our feet in the parking lot.

HAVE YOU EVER BEEN CONVICTED OF A SEX CRIME? — Sex crimes! This was too much. Sex and crime in one question. I was eleven. What did they mean? I put “N/A” which my sister told me meant “No Answer.”

I tore through the rest of the application to see if there were any questions about juggling, rolling out the barrel, make-up application/removal, or any of the things I practiced every day. Nothing. Must be in the practical.

Page three was all about drugs. I put N/A in all the drug question boxes. If only I had been filling this out six years later, I would have been able to fill page three front and back, opening up my chances for full scholarship.

HAVE YOU EVER BEEN CONVICTED OF MOLESTING A CHILD? — Oh, my dear Lord. Wouldn’t that fall under sex crimes? I was going to put “No Answer,” but then I thought of how me and Scoot Ryder would kiss every day behind the garage. Real Hollywood kisses, our lips tight and our faces pressed together hard. I thought of the first time he parted my lips with his tongue; we were frenching. His mouth tasted like the Swedish Fish penny candies he had eaten on the walk over to my house, his tongue a film of red gelatin.

Our relationship lasted all through junior high, where Scoot was the reigning Metal God. He had a tattoo, a fucking tattoo in seventh grade. I would have followed him around with a mattress strapped to my back if I could’ve. When it came time to move from frenching to third base, Scoot got scared. “Won’t that make us gay?”

“Make us gay? What are you talking about?” I answered all of his questions with questions for years, keeping everything simple like we were making toast. Scoot was easy to distract. Technically we were both minors when our affair began in grade school but there were no arrests or convictions so I just wrote NO. To eliminate all doubt, I added an exclamation point. NO!

DO YOU HAVE ANY TATTOOS? — In the mirror I saw the stars scratched on to my cheeks in medium-brown mascara. “No.”

WHAT’S THE LONGEST YOU’VE BEEN IN PRISON? — The presumption that I was, of course, a former inmate seemed like a trick question so I put “N/A.” This process was so intense but I knew it had to be and I was willing to give them what they wanted. There has to be an initial screening process in place in order to weed out the good clowns (like Willie Whistle), from the bad clowns (like John Wayne Gacy).

My signature signed, I stuffed the finished questionnaire into an envelope, minus the $75.00 check for the non-refundable application fee. My mom said, “No way,” when I asked her for the money, despite the passion of my begging. “Mom, please! This is my life we’re talking about!” The “this is my life…” part was in a movie, so I used it.

In the movie, it worked; Judith Light’s character screamed, “This is MY life!” to the ex-husband character who caved immediately upon hearing the words. The magic phrase didn’t work on my mother. I forgot we had watched the movie together and that she hated Judith Light way more than she hated clowns.

She was not budging on the application fee even if it was my life. She got real close to my face, very serious. “Clowns have miserable lives, Francis. Clowns die drunk and alone in their big shoes.” That was it. My mother had put her fears to their finest point.

I guess parents don’t dream that their kids will be clowns. My mom and all her sisters wanted me to be a priest, and told me that God had chosen me for the cloth. She meant it, too. The priesthood.

“You were meant to be a priest,” she insisted. “Father Hazebrook said so. A clown, Francis? No way. No way am I bloodying my hands with your demise.” Suddenly she was Pontius Pilate, washing her hands in an imaginary bowl she kept on her vanity, miming as she railed against clowns, using my own weapons against me. “A clown! My God, Francis.” She started to fan herself with a magazine, real dramatic. I think the “bloodied hands” number was in a movie, too, a Jesus movie she saw.

She acted as if she knew a whole bunch of clowns before she’d met my dad. As if her teen life was filled with unexpected shaving-cream pies to the face. Even now she shivers when someone mentions clowning. So does my sister, all of her friends, and most of the kids at school. “Oh, clowns scare me to death!” my sister always said at the Macy’s Thanksgiving Day parade when we were dragged up Fifth Avenue every year, exhausted and late from the three-hour drive, but she’s not dead yet.

It’s hip to act fearful of clowns and most Americans are not coulro-phobes, they’re compulsive liars. Clown hate is cool and runs unchecked in our society. If a clown molested you, okay then, clowning may not be your favorite form of entertainment. Getting diddled by a pervert in pointy make-up is a valid reason to harbor clown hate, and you should run from them for the rest of your life. Or you could face their sad painted faces head on and confront your fears. Whatever helps you sleep at night. I, personally, run to sedation rather than confrontation, but don’t listen to me. Seriously.

My mother, a notorious clown bigot, told me again that she would rather slice her face than give me the $75 application fee, enabling me to throw my life away. Then she started the miming again: slicing at her face with a butter knife, checking her wallet, and wiping away tears. She was good at it, using props and everything. Maybe she had her own broken dream of clowning before she handed her life over to the textile mills when she was twelve.

Everybody worked in one factory or another here, assembling pieces of parts that would go on to become the sole of a shoe or the fin of a rocket. I liked thinking that my mom built rockets but she didn’t. She built shoe soles.

Her mother before her worked in a knitting mill, loading yarn in repetitive motion onto large spools to be shipped. In her last years on earth, this repetitive motion was all she could remember. Sitting up in her hospice bed surrounded by strange faces, loading invisible yarn onto an invisible spool, she let the motion wash her, keeping her away from thoughts of bedpans and who these people standing by her bedside were. I wonder what my motion will be. I hope it’s not snipping.

The factory my mother worked in was a massive brick building with a thousand windows that had light blue paint over the glass, ensuring that nobody could see in or out. Just a blue glow from inside at night. When we’d drive by I’d imagine her inside the glow, hot glue and rubber tearing her small, tough hands. There had to be a way to get her out.

Money wouldn’t be an issue soon. Once they saw my juggling credentials, which I wrote on the back of the psychosexual question page, they would send for me. Also included was a stack of pictures of me clowning, a bit show-offy, but they needed to see that I wasn’t some junkie with nothing going for me. The one of me rolling out the barrel should cinch the whole thing with a belt.

After ringing the Pagans’ doorbell and saying my goodbyes and fuck yous, I walked to the bus station carrying a stick over my shoulder, with a red bandana tied in a bundle at the end of the stick. Inside were cigarette butts and matches, a few shirts, juggling balls and a sandwich with some Chips Ahoy. I waited around the station until a driver finally noticed me.

“Joining the circus, son?” He looked like Wilford Brimley, concerned and gentle. He recognized the jester in my stare. When we locked eyes, his hooded lids assured me that Wilford was a comrade. He would put me on his bus and take me away to Clown College.

“Yes, sir, the circus! They’re expecting me at the Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Clown College but my mom won’t drive me. I have ten dollars from the clown shows I do. Is that enough to get me to there?” I was walking towards his bus as I talked, pointing at the map on the catalog, knowing he would tell me to hop on.

“What’s your name, son?” said Wilford. I knew this line of questioning, where “What’s yer name?” comes before “What’s your phone number?” Soon he would want to call my mother and send me back. He was no friend to a dreaming clown. He was a traitor who wanted nothing more than to see me end up in some factory. Or the priesthood.

“What’s yer phone number, son?” The bristles of his moustache lifted to reveal filthy teeth. The next question in this series is always “Where do yer folks live?” so I took off before he could say another word, hoping he wouldn’t call the pigs. My sister once told me, as she puffed out the end of a joint, that all cops are pigs and I knew she was right. Wilford Brimley was a pig, too, I decided, as are all bus drivers.

In the rearview mirror of an abandoned station wagon, I painted on full clown face with the lotion and powder kit in my pouch, then headed downtown hoping to find my benefactor. Juggling three perfectly weighted rocks, I entertained the checkbook-balancing audience filtering in and out of the bank. If onlookers took notice of my evident gift, I would tell them “I can juggle four, you know,” baiting them to ask me to show them, and getting me the big payoff. Most of them just smiled and continued on with the tedium of their lunch breaks; some of them put spare change on the ground by my pouch, mistaking me for a common street clown. Not one person asked me to do four. They were all pigs, I would later tell my sister, every last one of them. I put one foot in front of the other, in exaggerated clown steps, and marched up the street.

Dinner was cold when I got home. Boiled beef and carrots. I got a can of sardines out of the cabinet and fed them to the cat. We sat outside and waited for the sun to go down, me and the cat and a can full of fish. Nine months later, my pouch stank of soured Miracle Whip and cigarette butts. It sat in the corner of my closet, the stick-and-bandana looking authentic at last, with food stains and holes big enough for dreams to fall from.

They could at least have sent a letter.