Читать книгу The Transformative Years of the University of Alabama Law School, 1966–1970 - Daniel Meador - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

2 The Law School Foundation and Law Alumni

ОглавлениеA group of interested alumni had established a Law School Alumni Association in the late 1940s. It mailed out an annual placement booklet and an occasional newsletter and held a luncheon at the annual meeting of the state bar. Those were all useful activities that served to foster institutional attachment. But the association had not undertaken any serious fund-raising.

Before my arrival the most valuable and farsighted step concerning private financial support was the creation in 1961 of the University of Alabama Law School Foundation. It is a nonprofit corporation whose mission is to receive, manage, and expend funds from private sources for the benefit of the law school. A leader in its creation was David J. Vann, who had been a year behind me in law school, also clerked for Justice Black, and was later mayor of Birmingham. He had obtained from me a copy of and largely followed the charter of the University of Virginia Law School Foundation.[4] The University of Alabama Law School Foundation’s board of directors included an impressive array of able Alabama lawyers.[5] But like the Alumni Association, it had not been actively engaged in fund-raising.

Because the foundation was a legal entity with tax-exempt status and an organized structure, I saw it as more promising than the alumni association as a vehicle through which we could secure substantial private support. However, the foundation would work in collaboration with the alumni association; the association president was an ex-officio member of the foundation board. Thus, energizing the foundation to launch a major campaign was one of my top priorities. Substantial private money was the key to moving the law school forward. Happily, the board rose to the challenge without hesitation. In the early fall of 1966, it resolved to mount an aggressive capital campaign and adopted an ambitious goal of $1 million. The campaign and the goal were endorsed by the University of Alabama Board of Trustees in November 1966.[6]

Although the foundation’s board included some of the best lawyers in the state, I thought broadening and diversifying its membership would increase its influence and prestige and enable it to reach more funding sources. Two ways to accomplish this were to bring in prominent lawyers who were alumni of other law schools and to include directors from outside Alabama. I thought these moves would also make the board seem less provincial.

To that end, over the next couple of years the board elected as directors: Douglas Arant of Birmingham, Truman Hobbs of Montgomery, and Irving M. Engel of New York, all Yale Law graduates; Marx Leva of Washington, J. Asa Rountree III of New York, Inzer B. Wyatt of New York, and Robert E. Steiner III of Montgomery, all Harvard Law graduates; and Claude E. Hamilton Jr. of New York and Prime F. Osborn III of Jacksonville, Florida, both Alabama law alumni. All of the out-of-state directors had Alabama connections and thus a special interest in helping in this unprecedented campaign to create a superior law school.[7]

In my first years, Sam W. Pipes III of Mobile was president of the foundation. He was succeeded by Edward M. Friend Jr. of Birmingham. Members of the board regularly attended its periodic meetings and tackled the fund-raising challenge with enthusiasm. Foundation leadership rested in its executive committee.[8] Those busy lawyers devoted an extraordinary amount of time to law school concerns. Among them, Howell Heflin—later to become chief justice of the Alabama Supreme Court and still later a U.S. senator—deserves special mention. He had been president of the foundation and had just come off a year as president of the Alabama State Bar. He had boundless energy and a deep interest in the law school. During the years of my deanship he spent more time on law school matters than any other alumnus. I marveled over how he could do it along with his law practice in Tuscumbia.

Primary targets of this fund-raising drive were law school alumni and families of deceased alumni. A difficulty we faced was the lack of a long-established tradition of charitable giving in Alabama and the South generally. The devastation of the Civil War and decades of depressed economic conditions had meant that there was little money for such. The situation was in sharp contrast to that in the Northeast where fortunes had been accumulated and private philanthropy was well-established. But since World War II, the South was becoming relatively affluent. Lawyers’ incomes were providing them with discretionary funds that had been rare before the war.

Another difficulty was the widespread view that a state law school should be maintained by the state legislature and that private funding was unnecessary. Overcoming that view and the lack of a philanthropic tradition involved an intensive educational effort. At the numerous bar association meetings and luncheons to which I was invited I took the opportunity to explain why state funds alone were not sufficient. Frank Rose and I stumped the state together with this message, appearing in the six largest cities. Our message had an evangelical fervor. Private funding was necessary to provide a “margin of excellence,” as Virginia Dean Hardy Dillard had put it. The public law schools of greatest distinction in the United States—for example, Virginia and the University of Michigan—relied heavily on private support.

Dr. Rose took me with him to New York to discuss the law school with representatives of the Ford and Carnegie foundations. We laid before them our aspirations for Alabama to become a leader in lifting Deep South legal education and research into the first ranks. But the law school never received a grant from either of those sources.

Otherwise, results from the Law School Foundation’s invigorated efforts were not long in coming. In the previous year, 1965–66, the foundation received $8,900 in contributions. In 1966–67, contributions increased more than seven-fold to $68,000. At the same time, the University-provided funds also jumped, as Dr. Rose had promised. For 1966–67, the law school budget was set at $407,308, compared to $315,501 the year before. These greatly enhanced financial resources from the combination of state and private money gave the school a boost, suggesting that it was on the way to a new level. There was a sense of real momentum.

A fortunate development at this moment was the election of Judge Seybourn H. Lynne as president of the Law School Alumni Association. Chief Judge of the U.S. District Court in Birmingham, Lynne was the most respected legal figure in Alabama. Within the foundation board there arose the idea of asking him, in his capacity as alumni president, to lead a newly organized and energetic annual giving program. We knew that most judges normally would not participate in fund-raising campaigns. But we hoped that with all of the fresh forward movement in the school, he might view this as a special case. I was dispatched to ask him to do this. From my short time in law practice in Birmingham, Judge Lynne and I were acquainted. I had appeared before him in a couple of matters and had met him on a few other occasions. We got along well, and I was one of his many admirers.

We met in his chambers. I updated him on developments in the law school and our aspirations for heightened excellence. I explained our ideas for the annual giving campaign and the reasons for it, saying that we hoped that once it was established it would be a permanent feature of the alumni association. The plan was to appoint a chairman for each class, to solicit his classmates; there would be competition among the classes to see which could produce the highest percentage of contributors. Essentially all we were asking him to do was to sign a letter to all alumni explaining the program and urging them to contribute. At the end of a good discussion, he said, to my great relief and pleasure, “You know my position on fund-raising, but I will make an exception here.”[9]

So with that, we launched the annual giving program in 1967–68. At the end of the year, the class of 1931, with W. Inge Hill of Montgomery as its chairman, came in first with 66 percent of its members participating, an extraordinary level of involvement among institutions of higher education. The widespread regard for Judge Lynne was undoubtedly an important factor in the success of that year. But once organized as it was, the program could carry on effectively into future years. Judge Lynne was succeeded as association president by Oakley W. Melton Jr. of Montgomery (my classmate and third-year roommate).

Another idea advanced at that time came from several former law clerks to U.S. Supreme Court Justice Hugo Black who were now practicing law in Alabama. They proposed to establish an endowed fund to commemorate the thirtieth anniversary of his appointment to the Court. Having myself been a law clerk to Justice Black, I immediately supported the idea. He was the law school’s most prominent alumnus (Class of 1906) and, of course, was nationally known. The hope was that a fund in his name would attract contributions from his admirers all over the country, reaching resources beyond Alabama. This effort was launched in 1967.

My memory is fuzzy on the details, but somehow arrangements were made for a reception in the White House at which the fund’s establishment would be announced. Unfortunately, on the eve of the event President Lyndon B. Johnson had to leave for Germany to attend the funeral of Konrad Adenauer. But the reception went off as scheduled on April 25, 1967, with Lady Bird graciously presiding in the president’s place. Vice President Hubert Humphrey gave an eloquent tribute to Justice Black, who was present. I presented him with a certificate from the Law School Foundation announcing the establishment of the fund. Hoping to stimulate interest among the guests, we had placed copies of a printed brochure describing the fund on tables in the State Dining Room, where the reception was held. This event gave the law school some much-needed national visibility.

Since 1954 when Justice Black joined the opinion of the Court in Brown v. Board of Education, he had been ostracized in Alabama. But that feeling was melting away. In the summer of 1968 he was invited to speak at the annual meeting of the Alabama State Bar in Tuscaloosa, and he accepted. This was a historic and somewhat emotion-filled moment, as he had not been back in his native state for well over twenty years. The Law School Alumni Association took advantage of the occasion by holding a luncheon in his honor at the University.[10]

The next significant development in our seeking enhanced financial resources came in 1968 when George Burns joined the University Development Office. In line with Dr. Rose’s commitment to the law school, Burns was assigned to help with our fund-raising work. He came from California where he had been involved in successful fund-raising activities for several colleges. He presented the foundation board with an idea which he said had worked effectively in California. The idea was to establish a selective organization of prominent lawyers and outstanding citizens from other fields, each of whom would pledge to contribute at least $100 annually to the Law School Foundation. This was an especially appealing proposal in that it would draw non-lawyer support, in keeping with our theory that the importance of the law school went beyond the legal profession and was a vitally important institution to the welfare of the state and for the preservation of government under law.

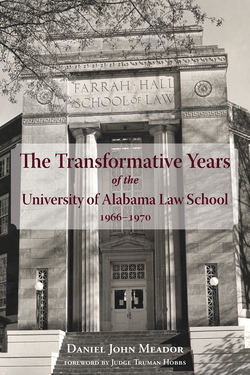

The board agreed with the idea and in the spring of 1969 established the Farrah Law Society. The name honored Albert J. Farrah, dean of the law school from 1913 to 1944, who was much beloved by students who had studied under him. This was at the time, as will be described later, when the Order of the Coif replaced the Farrah Order of Jurisprudence as the school’s honor society. So the new society kept the name Farrah alive and satisfied the older alumni. The foundation board chose Howell Heflin as the society’s chairman.

Selective membership was to be by invitation, creating what some might have called an “elite” organization, thus making membership more attractive and creating an incentive to join. Recruitment of members was to be by means of private dinners all over the state, hosted mainly by foundation directors but also by other alumni enlisted for the organizing effort. Twenty-seven dinners were hosted in all parts of the state. I attended all but three. Heflin attended more than twenty.

The project succeeded beyond all expectations. The original goal was 350 members by the fall. That goal was soon passed, and a new goal of 400 was set. That goal too was passed, and membership continued to grow. By the time of the inaugural dinner in Birmingham on October 24, 1969, membership totaled 576. That black-tie dinner was the high-water mark of our fund-raising efforts over the past three years. The principal speaker was Dean Bayless Manning of the Stanford Law School.

Over the next few weeks membership reached 612. Each member was presented with a handsome laminated wooden plaque, numbered, inscribed with his name, and signed by the chairman of the society, president of the foundation, and dean of the law school. With every member pledged to contribute at least $100 annually, this meant a yearly income for the foundation of at least $61,200, in addition to other contributions. To me, this development was a resounding vote of alumni confidence for what had been done in the law school in the past three years and for the direction it was taking. In 1968, after expenses, total foundation assets were $335,429, a figure unimaginable a couple of years earlier.

From a twenty-first century vantage point, the sums mentioned here may seem small. But in the late 1960s they were significant. The law school’s annual tuition for in-state students was only $450. Experienced law professors throughout the country were paid less—often much less—than $20,000 annually. Although the foundation’s efforts over these four years were a huge boost to the school, it was disappointing that no major gift was received, no blockbuster gift of at least several hundred thousand dollars, no gift at the level the Atlanta lawyers had talked to me about.

Georgia was on my mind as we progressed with our fund-raising efforts. I wondered how we compared with that law school. This was a matter of special interest since, as earlier reported, I had been briefed on their grandiose aspirations in January 1964. I found out on November 18, 1967, when I participated in an elaborate dedicatory ceremony to mark the opening of their renovated and enlarged law school building. The principal speaker was Justice Black. The impact of the Atlanta money was obvious. In addition to an excellent building, they had established endowed professorships and lectureships and had expanded the library collection. Of course, they had a three-year head start on us. They also had a governor giving them strong, affirmative support, something we did not have. That scene in Athens strengthened my determination to equal and exceed what I saw. If they had done it, why couldn’t we?

As a further step toward unifying the alumni and heightening their sense of institutional attachment, we undertook, with foundation financial support, the first-ever publication of an alumni directory. This turned out to be a more substantial project than had been envisioned. In some instances, records were surprisingly incomplete. Much research was required into University archives and law school files, but eventually every graduate was identified. The effort resulted in the publication in 1970 of the University of Alabama Law School Directory of Graduates, 1872–1970. As the title indicates, persons who attended but did not graduate were not included. The directory covered the entire history of the school, from its opening through the class of 1970. It included a list of all faculty members from the beginning, and all graduates, both living and dead, listed alphabetically and by class, with a geographical listing of the living. It is an important reference work on law school history, providing information not readily available elsewhere and certainly not available in any other single publication.[11]

To summarize, nearly everything that had to be done to lift the law school to a higher level depended on securing substantial private funds. Nothing was of higher priority. I estimate that over the four years of my deanship at least half of my time was spent on fund-raising—traveling to attend alumni gatherings and to meet with prospects, writing letters, on the telephone with foundation board members and others. Fund-raising was rarely out of my mind. It was an almost messianic obsession. But I thought it essential to overcome long years of inattention and to catch up with the best of the law school world. Though often stressful and tiring, it was interesting and enjoyable because of the associations it involved with foundation board members and other alumni. They were the strongest source of support. Their enthusiasm for the law school and the time they invested in fund-raising, though they were busy practitioners, was impressive. I was and always have been deeply grateful to them. Without them, much of what was accomplished during those four years would not have been accomplished.

This is a good point to mention the role of my wife, Jan. Throughout the four years of my deanship she was heavily involved in law school activities. The foundation board met regularly in Tuscaloosa, and she nearly always held a reception for the directors at our house. She was particularly good at alumni relationships. We had faculty members to dinner from time-to-time, and Jan assisted in entertaining visiting lecturers and professors. She participated in the Law Wives activities and enjoyed that association. For occasions generally, she served as unofficial law school hostess. She was a great asset to the school and to me; she could hardly have done more.