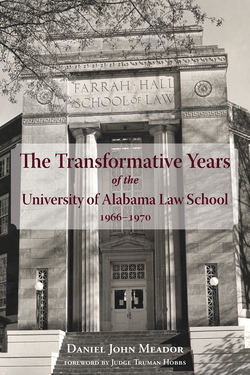

Читать книгу The Transformative Years of the University of Alabama Law School, 1966–1970 - Daniel Meador - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Foreword

ОглавлениеTruman Hobbs

United States District Judge

In the summer of 1965, Dr. Frank Rose, president of the University of Alabama, decided that the University of Alabama Law School needed a dean to advance it further along the road of academic excellence. He contacted a young native Alabamian, Dan Meador, a graduate of the University of Alabama’s Law School. Meador in 1965 was a professor at the University of Virginia Law School. Dr. Rose requested that Professor Meador come back to head his home-state law school as its dean. Meador accepted the call—pending completion of a Fulbright Lectureship in England—and more than forty years later he has written this book describing the vision he had as the new dean and the success he had in implementing that vision in the four years that he served.

He knew that success in achieving the vision could not be possible by a dean acting alone. The book describes his efforts and success in enlisting a number of able graduates, faculty, and friends of the law school to join in the vision for an even better law school. The new dean chose well in those whom he asked to serve. Many were busy lawyers in the state of Alabama, and the hard work they undertook was a credit to them and was vital to achieving the new vision for the law school.

Dean Meador had the requisite background for the task he was assuming. He held degrees from Auburn University, the University of Alabama Law School, and Harvard University. He had served as a law clerk to a distinguished University of Alabama Law School graduate, Supreme Court Justice Hugo L. Black. He was chairman of the Southeastern Conference of American Law Schools and had served on American Bar Association accreditation committees to evaluate the law schools at Duke and Vanderbilt.

Meador took as his challenge the moving of the Alabama Law School to a higher level of quality in every respect. This challenge required securing substantial funding beyond state appropriations, which required enlisting the busy lawyers mentioned above, who also wanted the best for the Alabama Law School. The state of Alabama, and the South generally, had not previously established a strong tradition of charitable giving by its attorneys. There was a generally accepted view that a state law school should be supported by state funds. But more and more state schools were finding that state funds alone were inadequate to provide the improvements that were wanted if a state law school was to achieve the desired level of excellence. In Meador’s first year as dean of the Alabama Law School, he increased contributions from private sources by more than sevenfold. Dr. Rose also fulfilled his promises and the University increased the funding that it provided to the 1aw school by almost a third.

Great progress was made at the University of Alabama Law School in the four years that Dan Meador was its dean. President Rose was pleased with the progress and was very supportive of Meador’s vision, but in 1969 he resigned as president of the University.

Soon after, Dean Meador was asked if he would return to the Virginia Law School to take over the James Monroe Professorship. He had always expected someday to return to being a full-time law professor, which had more personal appeal to him than the administrative responsibilities of a dean.

Dr. Rose had been beneficial in effecting the changes made under Meador’s deanship, but Meador felt that the new president was backing off from these commitments. It was difficult to understand why several of the faculty at the law school and the new president of the University of Alabama did not share Meador’s enthusiasm for the changes that had been initiated, leaving him with concerns that the improvements at the law school would not be sustained. He accepted the prestigious professorship at the University of Virginia Law School and returned to the classroom.

Meador was wrong, however, in fearing that the improvements at the University of Alabama Law School would unravel under a different president; most of the achievements of Dean Meador and those who worked with him to fulfill his vision for the law school appear to be firmly in place, evidence of the skill and craftsmanship of those who worked to accomplish these goals. This book reveals the blueprint for the efforts that achieved so much for the law school during four short years.