Читать книгу Postcards from Auschwitz - Daniel P. Reynolds - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеIntroduction

The Auschwitz-Birkenau Memorial and Museum saw record attendance in 2016, receiving more than two million visitors from all over the world. There have been so many tourists to Auschwitz since its establishment as a memorial in 1947 that the concrete steps in the former barracks, now the main exhibition halls, have been worn smooth and concave from heavy foot traffic. Since 1999, when the memorial museum launched its website, the number of tourists to Auschwitz has climbed dramatically.1 Accommodating such numbers presents enormous logistical challenges for crowd control, for scheduling, and for the provision of personally guided tours in seventeen different languages each day. In the face of such massive demand, how does the memorial provide its visitors with a meaningful experience that amounts to more than macabre voyeurism or crass consumerism? Despite the challenges in managing a site that was never intended to host crowds of tourists, the memorial’s mission to remember and prevent future barbarism attracts more people today than ever before. The museum’s director, Dr. Piotr M. A. Cywiński, explains the global lure and core message of Auschwitz in the present: “In an era of such rapid changes in culture and civilization, we must again recognize the limits beyond which the madness of organized hatred and blindness may again escape out of any control.”2 It is tempting to read Dr. Cywiński’s comment as self-referential, as if the description of controlled madness applies as much to Auschwitz tourism as to the events the museum commemorates and documents.

The first impressions at the Auschwitz-Birkenau Memorial and Museum can indeed be chaotic, with long lines at the ticket windows, tour guides frantically rounding up their groups, a cacophony of languages, a parking lot full of buses entering and exiting. Tourists ostensibly come to learn about the perils of “organized hatred and blindness” that generated the Holocaust; they are challenged to put the values of tolerance into practice as they share limited space with one another. Sightseers vie for elbow room to take photos of confiscated luggage, canisters of poison, prisoner uniforms, crematoria furnaces, and other reminders that more than 1.1 million people were murdered here between 1940 and 1945. They fill the museum bookstores, they stand in line to pay for refreshments and use the restrooms, and they crowd the post office window to mail postcards of the memorial to their friends and family back home. What remains to be seen is whether these visitors take any lessons with them after they leave.

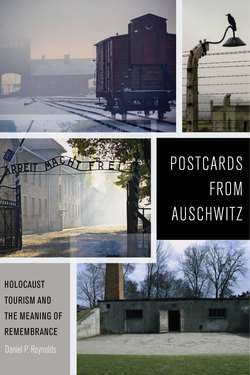

It is this image of buying postcards at Auschwitz that I choose to represent the phenomenon at the heart of this book, “Holocaust tourism.” Sightseeing connected to the genocide of European Jews and the murder of millions of other victims will inevitably strike some as a cringe-worthy, inauthentic, and commercialized practice that has no place in connection to a history as inviolable as the Holocaust.3 After all, the problem of understanding Nazi crimes through earnest scholarship or committed art is vexed enough without entering the profane realm of tourism.4 At first glance, postcards are emblematic of the tackier side of tourism, often depicting clichéd scenic views in garishly enhanced colors, so to discover their presence at the most notorious site of Nazi mass murder seems somewhere between distasteful and obscene. Postcards reflect the presumed superficiality of tourism, a momentary and forgettable act of sharing an image.5 But postcards have a flip side, literally and figuratively, making them a good metaphor for tourism as a practice that allows for more sophistication than meets the eye. A postcard invites travelers to inscribe their own commentary on the back, to direct the postcard image to a particular audience and to accompany it with a commentary that may undercut the representation of the place the card is meant to promote. Postcards have the capacity to reveal more than the tourism industry authorizes, and they offer a medium for tourists to exercise a degree of critical agency (if they so choose). In contrast to the medium’s cliché, postcards from Auschwitz usually exhibit muted tones and portray somber images, indicating a different mode of tourism that promotes reflection, even unease, over enjoyment. Tourists who send a postcard from a place of atrocity are likely to be more self-conscious about what they inscribe on the back, since their own text exposes them to critique by their readers. What could one say on the back of a postcard that could possibly be commensurate with the history of Auschwitz?

As valid as misgivings about postcards from Auschwitz and the phenomenon they represent may be, Holocaust tourism continues to flourish. The recurrence of genocide around the world should make us skeptical that such tourism has done anything to prevent the kind of insanity and violence that, more than seventy years ago, murdered six million European Jews; yet visitors to Holocaust memorials typically express appreciation for the opportunity to learn important lessons about humanity and its capacity for violence. And they do so at a growing number of Holocaust memorial sites in places as far away from the original event as Sydney and Shanghai.6 Tourists in Washington, DC, wait in long lines to secure limited passes to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in similar numbers, with 1.62 million visitors in 2016.7 Since its completion in 2005, the number of visitors to the information center of Berlin’s Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe has steadily increased from 360,000 to a record of 475,000 in 2015—a number that does not include the many visitors to the outdoor memorial who do not enter the information center.8 These numbers are part of a larger picture about tourism of all kinds, which UNESCO characterizes as the world’s largest industry and one that is expected to continue to grow globally.9 Our highly visual global culture seems increasingly obsessed with seeing that which most of us, thankfully, will never endure. It is the job of scholars to offer an account of tourism’s motivations and complexities, to take seriously its modalities of signification, to acknowledge both its appeal and its peril, and to put forth the questions that prompt deeper reflection.

At present, there has been little effort to take tourism’s role in Holocaust remembrance seriously and attempt to understand not only its popularity but also its possible value. The two terms—“Holocaust” and “tourism”—have only recently been brought together, usually in a context in which the writer can disavow the phenomenon.10 Indeed, the study of tourism of any kind, let alone Holocaust tourism, is something of a marginal field of inquiry within the academy. Those who research tourism have struggled to have their inquiry taken seriously, combatting well-established attitudes within the realm of scholarship against that which is seen as commercial or frivolous. In contrast, the Holocaust occupies an overwhelming position in Western thought, having defined the trajectory of research in the humanities, social sciences, and even the natural sciences like no other event since 1945. Unlike the study of tourism, the study of the Holocaust has become so firmly established in the academy that some approaches have achieved the status of doctrine, for better or worse. In focusing on Holocaust tourism, this book questions the attitudes and beliefs that inform the study of both the Holocaust and tourism, asking if they are still adequate to address the continued prevalence of the Holocaust in the Western imagination or to acknowledge the new realities of tourism as the world’s largest industry.

I enter this discussion as something of an outsider, trained in the field of German studies with a focus on literature. While the Holocaust occupies a central place in German studies, it is a field in its own right that draws on research from numerous other disciplines in the humanities and social sciences. But it is safe to say that tourism has been, at best, a marginal topic in both German studies and Holocaust studies. To undertake an analysis of Holocaust-themed tourism, I have turned to work undertaken largely by anthropologists, whose questions about travelers have helped me immensely in framing my approach. Holocaust tourism is an unwieldy topic that challenges the boundaries of disciplinary knowledge while simultaneously challenging the boundaries of comfortable discourse. The topic fuses two realms of experience—that of the Holocaust as an unparalleled historical event, and that of tourism as a popular mode of intercultural encounter—that are generally kept separate. This book argues that anyone interested in understanding Holocaust tourism engages by necessity in a broadly interdisciplinary inquiry. It draws upon the numerous inquiries into both the Holocaust and tourism that, despite their abundance, have remained largely disconnected from one another. In connecting them, I also rely on personal experiences and observations shared by many Holocaust tourists, as well as my own. The goal here is not to “correct” either disciplinary or non-academic accounts of the Holocaust or tourism but, rather, to engage in a conversation about both the pragmatics and the ethics of Holocaust tourism, to identify problems, and to acknowledge possibilities for contributing to public memory.

The task of theorizing Holocaust tourism is daunting, not least because of the seemingly incommensurate loci of the Holocaust and of tourism in the imagination. The disciplinary developments of Holocaust studies and tourism studies have generated insights and methodologies that have made sense within certain disciplinary confines. Holocaust tourism, however, challenges both fields by exposing the lacunae between the academic theory and an emerging form of practice that neither field has been particularly eager to address.

“Tourism” and “Holocaust”: Disciplinary Responses

While the Holocaust has had a prominent role in defining intellectual life in the West since World War II, tourism has received more limited scrutiny within academia, having been marginalized until recently even by those fields where it now flourishes. The more limited interest in tourism studies no doubt relates to the cultural bias against tourism as a lowbrow form of cultural experience.11 Unflattering stereotypes abound both inside and outside academia, portraying tourists as uncritical consumers who exploit people marketed as Others from exotic places.12 The difference between the Holocaust and tourism in terms of their perceived importance presents an awkward situation for the student of Holocaust tourism. After all, what could differ more from tourism and its presumed triviality than the Holocaust, around which a complex array of philosophical, ethical, historical, and aesthetic approaches have evolved in response to a cataclysm so profound as to challenge the very foundations of knowledge? Consequently, if tourism is regarded chiefly as a problem, then Holocaust tourism must be a particularly odious form of the activity, grafting the hopelessly banal onto the utterly momentous.

But in regarding tourism, including Holocaust tourism, as a problem to be overcome rather than a practice to be understood, scholars preempt any analysis of this growing phenomenon. In order to address seriously the legitimate concerns one may have about the ethical value of tourism, one must first be willing to acknowledge that tourism is tremendously diverse, encompassing a vast range of motivations, topics, locales, and ideologies. Only by allowing for that variability can one hope to understand how—or if—one can distinguish visits to a death camp from visits to any historical museum, ancient ruin, or medieval cathedral. As we will see, casting a visit to Auschwitz as the ethical equivalent of a trip to Disney World flattens both kinds of travel into meaningless diversions, denying the potential for even a modicum of value in either instance.13 A dismissive stance toward tourism prevents more meaningful analysis in more than one way. First, it suggests that destinations themselves have no intrinsic qualities that resist tourism’s presumed superficiality. Second, it regards tourism as an undifferentiated practice based primarily on consumerism and entertainment rather than education or personal enrichment. But tourism is not simply an empty form into which one pours arbitrary content, nor are tourists itinerant automatons passively swallowing the latest marketing schemes from the travel industry—at least, not in all cases. Rather, tourism is a multifarious form of cultural encounter whose aims may or may not include entertainment and shopping, education about history, practice of a second language, appreciation of art and architecture, visits to sites of trauma, or pilgrimages to sacred places. Tourism has rarely been a matter of simple diversion.

The recent field of tourism studies arose in the social sciences in the 1960s and 1970s, particularly in the fields of political science, economics, sociology, and most prominently, anthropology.14 Whether focused on tourism to sites of pleasure (e.g., so-called 3S tourism—“sea, sand, and sun”) or to sites of disaster (as in what the business scholars Malcolm Foley and J. John Lennon have called “dark tourism,” which could include Holocaust tourism),15 their point of departure emphasizes the gathering and interpretation of data through empirical methodologies and neutral terminology. Tourism studies defines tourism, differentiates among its various modes, and explains its significance to those who participate in it and are affected by it.16 It documents the flows of people and currency, catalogs the rationales for different kinds of travel, and categorizes the experiences shared by tourists. In these studies, tourism emerges as a differentiated field that encompasses the vacationer, the business traveler, the shopper, the sunbather, and the adventurer as well as the student, the researcher, and the pilgrim.

The wealth of information about types of tourism forms the basis for important ethical and ideological considerations, such as tourism’s role in the exhaustion or preservation of natural and human resources or the ways in which the tourist’s experience of foreign culture is authentic or staged.17 Feminist scholars address the gender politics of tourism, focusing, for example, on the intercultural collision of values about gender roles or the economic impacts of tourism on an indigenous population’s distribution of wealth along gender lines.18 A related area of tourism study explores the link between the exotic and the erotic, focusing on tourism’s potential for sexual exploitation of indigenous cultures, most obviously captured by the study of sex tourism.19 Marxist anthropologists portray tourism’s role in the spread of globalized capital, whereby locations become tourist markets and the labor of performance commodifies indigenous culture for the traveling consumer.20 An emerging area of tourism study takes up the question of tourism’s sustainability, concerning itself not only with the economic and cultural preservation of the sites tourists “consume” but also with the ecological impacts of tourism on the natural environment.21

Historians have also contributed crucial insights into the evolution of touristic practices, reminding us that tourism is both older and more varied than its most popular current manifestations. The origins of tourism in its modern form are a topic of some debate, but many argue that tourism has its origins in religious pilgrimage.22 In that sense, Boccaccio’s Decameron or Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales can be regarded as early portrayals of a strain within tourism that continues to this day. (The distinction between the tourist and the pilgrim is a recurring motif in the study of Holocaust tourism and points to the risk of overly essentializing these two identities.) Tourism also has roots in commerce, as the development of trade routes produced tales of distant lands and cultures, luring others to embark on their own adventures. The word “tour” became more commonly employed in seventeenth-century Europe to refer to an organized form of travel to a “canon” of sites. This was the Grand Tour, the purpose of which was to educate the wealthy sons of aristocrats in the languages and arts of neighboring countries.23 Of course, both the pilgrimage and the Grand Tour participated in tourism’s commercial and entertainment aspects, necessitating lodgings, meals, and the usual diversions along the way. With the emergence of the middle class, particularly since the industrial era, and the development of mass forms of transit and communication, tourism began to display some of its more modern manifestations as a mass phenomenon—and gave rise to the inevitable complaints about the entry of the masses into a previously elite arena. With the development of tourism as a mass phenomenon, the more commercial aspects of tourism have tended to eclipse the social capital attributed to previous eras, but that should not imply the erasure of tourism’s educational value. The multiplicity of historical roles played by the tourist—pilgrim, trader, or student—has important implications for Holocaust tourism, where the tendency to distinguish between the pilgrim and the tourist can be problematic. Tourism resists stable forms of identity; indeed, some forms of tourism may bring about a profound destabilization of identity. That is especially the case with Holocaust tourism.

If historians have reminded us of the fluidity of touristic practices over time, anthropology has documented the ways in which tourism continues to evolve and to present new challenges. Anthropologists began to take up the study of tourism in earnest in the 1960s, and by the 1980s one could identify a fairly coherent field of tourism studies within anthropology. While economists and political scientists had certainly contributed empirical analyses of the phenomenon, the emergence of tourism studies in anthropology happened to coincide with the field’s “linguistic turn,” that is, its receptivity to postcolonial theory and to poststructuralist theories of language. So when anthropologists began pursuing tourism studies, they did so with a critical awareness of the limitations of empirical methodology.24 Emerging from their self-critical turn in the wake of postcolonial critique, anthropologists sought to understand their own position as visitors to other cultures and their own production of the foreign and the exotic as discursive formations.25 In other words, anthropologists began to appreciate the ways in which social science did not simply observe phenomena but also participated in and even produced them through social-scientific discourse. Anthropology’s investigation of culture based on otherness, it turned out, helped to produce the very otherness it sought to explicate. As the anthropologist Dennison Nash explains, this insight has led some within anthropology to shun tourism studies. “To be accused of exploitation is a very black mark indeed for anthropologists. So in the anthropological community the study of tourism could be construed as an invitation to guilt by association with things that anthropological work definitely is not supposed to be: the pursuit of pleasure; superficial observation; and the exploitation of peoples.”26 But, Nash and his colleagues argue, the study of tourism actually provides an opportunity for anthropologists to reflect both on the ways in which anthropology is itself complicit in the packaging and selling of the Other and on the ways in which tourism, so easily maligned, is itself a more complicated practice than meets the eye.

The thrust of anthropological approaches to tourism is the encounter between two cultures, that of the tourist and that of the native. Tourism is one of the ways in which intercultural contact is managed, negotiating what is available from the native for display or performance and what is desired by the tourist for consumption. While the aim of social-scientific inquiries into tourism is to offer an empirically based account of its various forms and practices, the research often leans toward stressing the troublesome aspects of tourism, informed by the anthropologist’s ideological commitments—hence the abundance of Marxist, postcolonialist, environmentalist, and feminist approaches to tourism. The result is a dominant portrayal of tourists as the “exploiters or unwitting representatives of exploiting forces such as international hotel chains, airlines or other national or international agencies which have become involved with native populations.”27 By the same token, the native is regarded either as vulnerable to exploitation, susceptible to cultural contamination, or complicit in the less sincere aspects of the tourist industry.28

Such accounts are critical and point to real problems in tourism, but they do not exhaust the range of touristic practice that occurs in the world today, nor do they claim to. Indeed, anthropology regards the study of tourism as a wide-open field in its early stages of development. Nor should we assume that a field as large as tourism can be exhausted by anthropological inquiry. For one thing, anthropology is predicated on the intercultural encounter between the foreign and the native or between the present and the distant past. But not all modes of tourism emphasize cultural difference. The visitor to historical museums, for example, may be in search of some affirmation or deepening of an already-embraced cultural identity. Similarly, the heritage tourist may be in search of some knowledge about one’s own ancestors so as to better comprehend one’s current position at home. Meanwhile, the eco-tourist travels with a critical awareness of tourism’s impact on the environment; in an effort to reduce the harmful effects of poorly managed resource exploitation, the eco-tourist attempts to minimize or even eliminate the harmful environmental and social effects typically associated with mass tourism. While such types of tourism can be evidence themselves of a kind of unequal cultural dynamic (e.g., the unequal distribution of economic resources required to engage in heritage tourism or ecotourism), there are motivations at work in the individual tourist’s journey that resist a reduction to intercultural encounter between natives and foreigners.

As we shall explore in the chapters ahead, Holocaust tourism is another mode of tourism that cannot be contained so easily by the familiar paradigm of the foreign and the native. In the context of the Holocaust, one must question if the notion of culture has any real meaning at all, unless we want to speak of an encounter with the disappearance of culture. When one enters the grounds of a former concentration camp or visits streets once located inside a Jewish ghetto, one is confronted with absence: the absence of those who made the place one of significance for the tourist. We confront the inherent paradox in the phrase “Nazi culture,”29 where the traces and relics we seek once aimed for the fulfillment of a racist fantasy of Aryan superiority by erasing a culture marginalized as Other. Instead of culture understood as the signifying practices of life, we come upon the death of culture. In the vacuum created in such places, we erect a substitute—a culture of memorialization. Or of amnesia. Different locations manage the dialectics of absence and presence in different ways, and that variety will be one of the recurring topics in the chapters that follow. The point here is that Holocaust tourism complicates the anthropological understanding of tourism as the encounter between foreign and native cultures by seeking something more radical than cultural difference—cultural destruction.30

There are other reasons not to cede the cultural analysis of Holocaust tourism, or of any other kind of tourism, solely to anthropology.31 As a social science, anthropology regards tourism as interconnected with other modes of making sense of the world and sees its diverse manifestations as instances of a larger phenomenon subsumed under the name of “culture.”32 Touristic encounters in turn enter into some relation, whether affirmative or critical, to other forms of cultural expression back home. As one manifestation of culture among many, tourism provides a lens through which the ethnographer locates particular beliefs and values that mediate the encounter of the traveler with a new location. While the practices and beliefs of the tourist may become the subject of theoretical (e.g., feminist, Marxist, poststructuralist, ecological, economic) analysis, the anthropological fieldwork of tourism studies is premised on the close observation of touristic behavior disentangled from the personal biases of the anthropologist. The anthropologist’s approach to tourism necessarily embraces a form of cultural relativism, in which one culturally positioned subject (the anthropologist or ethnographer) documents the signifying practices of another culturally positioned subject (the tourist), preferably in its own terms.33

Here again, Holocaust tourism presents challenges to anthropological assumptions. Given the Holocaust’s positioning within Western thought as a limit case of morality, an exemplar of ultimate evil, the anthropological commitment to observation must stumble in the face of the moral imperatives that the Holocaust demands. Observation of atrocity unaccompanied by an expression of moral condemnation risks the appearance of indifference, complicity, or approval. In the case of Holocaust tourism, the object of study is not just any kind of travel but, rather, travel to sites where Western humanistic and scientific values (of which modern anthropology is one manifestation) utterly collapsed.34 The rationality that shapes anthropology (and all modern science since the Enlightenment) itself becomes suspect in its encounter with the Holocaust. After all, barbarity reasserted itself under the Nazi regime with unparalleled destruction, despite the advances of the Enlightenment’s promise toward emancipation from ignorance and its humanist principles of reason and equality.35 Can there be reliable, accurate, or adequate representations of the event that do not reinstantiate the instrumental logic that enabled the Holocaust in the first place?36 This epistemological problem, first articulated in 1944 by the philosophers Max Horkheimer and Theodor Adorno in Dialektik der Aufklärung (Dialectic of the Enlightenment), and further developed by Adorno in subsequent works, has proven generative of an immense body of scholarship.37 The anthropology of tourism certainly affords a window onto one way of confronting the genocide, but like any window, it cannot uncover what lies outside of its frame. The questions arising from Holocaust tourism exceed any anthropological inquiry into touristic practices and cultural transfers between the foreign and the native.38

Anthropology is hardly unique in its limitations; if anything, the field models an exemplary openness to influences from both scientific and humanistic disciplines beyond its walls. But even a hybrid of scientific observation and interpretive semiotics cannot hope to offer anything like an exhaustive account of the Holocaust. Any effort to comprehend or portray the Holocaust through disciplinary knowledge confronts problems that exceed disciplinary expertise.39 Put simply, the Holocaust is too vast, too immense an event to contain within traditional disciplinary approaches.

Take the example of Holocaust testimony, which alone “not only refers to statements elicited from survivors by courts of law or simply for the historical record, as well as to the chronicles, diaries, journals and reports produced during the war and written memoirs and oral history produced after it, but also frequently encompasses other modes of expression to which survivors have had recourse, such as the short story, the novel, and lyric poetry.”40 As the literary scholar Thomas Trezise makes clear in his work on the reception of Holocaust testimony, if the act of bearing witness to the Holocaust exceeds any single genre’s representational strategies, then efforts to listen to and respond to such acts of witnessing must also draw on many kinds of understanding. Even if the object of study for anthropologists is Holocaust tourism and not the Holocaust itself, the underlying event that motivates such tourism will demand a historical and a moral reckoning that cannot be kept at bay by a desire to police disciplinary boundaries. Indeed, in understanding cultural practices as interconnected, anthropology itself acknowledges that Holocaust tourism must be understood alongside many other forms of Holocaust memorialization, which in turn will inevitably call on multiple forms of knowledge. To understand Holocaust tourism, one has to engage with debates in philosophy, historiography, theology, literary analysis, art history, and many others that have asked, What is to be remembered? How is it to be remembered? and What lessons may one learn or not learn from the event?

Tourism and the Representation of the Holocaust

While no single account can claim to provide complete knowledge of the event, one must nevertheless approach the Holocaust from somewhere, and how one approaches the Holocaust is simultaneously an epistemological and an ethical choice. The question of how to represent the Holocaust—through which disciplinary tools, which media, and which institutional structures—unavoidably engages with an ethics of representation. Take again the example of survivor testimony. How does one weigh testimony and take into account the fragile, sometimes unreliable nature of human memory? How does one portray the victims’ suffering without turning it into a spectacle? Holocaust museums and memorial sites must address these questions and others as they curate their exhibits and manage flows of tourists, who in turn are seeking a personal encounter with testimony in a place that avers authenticity. As a highly (but not exclusively) visual practice, the representation of testimony at such places, whether through documents and photos or through videotaped interviews, always negotiates the boundaries between knowledge seeking and voyeurism.41

As with written accounts of the Holocaust, sites of remembrance make choices about the specific stories they want to tell, which beginnings and endings to emphasize. Since there is no shortage of stories to relate, Holocaust representations, including those encountered in tourism, produce many “emplotments,” each different in some way from the next.42 Did the Shoah start with the Wannsee Conference of 1942, or the Nuremberg Laws of 1934? Perhaps its beginnings must be sought even earlier, in the anti-Semitic propaganda of the NSDAP (the National-Socialist German Workers Party, i.e., the Nazis) that was already on display for all to see in the 1920s. As for its end, many survivors of the Holocaust still bear with them a trauma that extends their experience of victimization into the present. The traumatic experiences of victims impose ethical obligations on those who listen to and represent testimony.43 One major challenge for Holocaust studies has been to recover historical knowledge from traumatic memory, since trauma implies a rupture—an inability or, at least, a difficulty—in rendering experience into a coherent narrative. The translation of individual trauma into collective memory is further complicated by the fact that not all individuals process trauma in the same way.44 What’s more, the category of trauma may account for some memories of the Holocaust but not all, so the nature of Holocaust memory cannot be reduced to the traumatic without obscuring non-traumatic memories that recall the event. Finally, recent theories see collective trauma as transgenerational, suggesting that the Holocaust has not finished shaping lived experience.

The variety of accounts of the Holocaust is also reflective of the vast geography in which the event unfolded, requiring immense levels of bureaucratic coordination, the active participation of thousands of perpetrators, and the passivity or quiet approval of millions of bystanders. Tourism, as an engagement with space, confronts the Holocaust’s physical immensity and its many variations of scale, location, and execution, as well as the differences in how its traces and artifacts are preserved from one place to another. While the earliest Holocaust memorials were the remains of liberated camps in Europe, the history of Holocaust memory has evolved from a strictly European experience to a global one.45 Since the end of the Cold War, many of the camps that previously lay on the other side of the Iron Curtain now have become part of a much more freely moving and thriving tourism industry. One result of the freer flow of tourism after 1990 is that sites previously administered under a more narrowly national or ideological perspective now partake in an increasingly international, even global, network of remembrance. To cite one example, the cooperation among the Auschwitz-Birkenau Memorial and Museum, the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, and Yad Vashem in Jerusalem illustrates that Holocaust memorialization is indeed an example of what the sociologists Daniel Levy and Natan Sznaider call “cosmopolitan memory,” a term they use to describe the interplay between local values and narratives and distant ones that are increasingly linked by modern technologies of travel and communication. Local and global practices around Holocaust memorialization and education are now thoroughly intertwined, often leading to debates about the local versus the global ownership of Holocaust memory.

Tourists who travel to multiple sites of Holocaust memorialization develop that network of cosmopolitan memory by comparing one act of remembrance with another. Tourism ensures that those who administer Holocaust memorials appeal to an increasingly sophisticated, diverse touring public that brings a wide range of experiences and knowledge to the sites it visits. The variations that tourists encounter from site to site reflect both the different histories of these sites, the ideologies of the regimes that inherited the task of preserving them, and the different resources available for administering those sites. For example, remote extermination camps such as Sobibór and Bełżec in eastern Poland reflect, among other things, the administrative reach of Heinrich Himmler’s SS on the heels of German military victories in the East, the determination to carry out killings in secrecy, and the grim logic of systematized murder from arrival to cremation. They also reflect the limited resources in postwar Poland for preserving them and the ideological hindrances to remembrance of Jewish suffering. Meanwhile, a site like the House of the Wannsee Conference reminds the tourist of the so-called desk perpetrators, the bureaucrats who coordinated the “resettling” of Europe’s Jews from distant administrative centers, and its postwar history also displays the shifting value placed on confronting the Nazi past in postwar Germany. The disparities in the ways in which these sites are administered today points to the different memorial cultures that have evolved over the course of the last seventy years in Poland and Germany.

The variety among Holocaust memorial sites also raises the very politically charged issue of whom to include among its victims, since the persecution of other groups, such as the Roma people or the mentally and physically disabled, were no less abhorrent than the murder of Jews.46 Sites of Holocaust tourism respond to this challenge in a number of different ways, with important and often controversial implications for the role of Holocaust memory in different contexts. Indeed, the acknowledgment of the Holocaust as the destruction of European Jewry was slow to emerge as the dominant narrative at many of the camp memorials, where narratives of liberation, martyrdom, or political persecution first took precedent. For an example that we will explore further in the following chapter, the earliest remembrances at Auschwitz emphasized Polish victimization and made little reference to the distinct fate of the Jews, the vast majority of whom were deported there for immediate extermination. Tourism has provided a platform from which to witness those transformations.

Tourism depends on the willingness of travelers to help create the experience they are seeking and even to hold sites accountable for their management. Tourists exercise considerable agency over how much they will contemplate, what they will or will not see, which routes they will take, whether they will pose questions of their guides, or even how compliant they will be with guidelines. Agency is a prerequisite for the educational function many Holocaust memorials and museums serve, which includes unearthing and preserving sites of perpetration, housing invaluable archival resources, and providing educational programming. This point also serves to remind us that tourism and education have always shared a link and that the distinction between the tourist and the researcher or student is at best a matter of degree, not kind. Still, non-specialized visits to Holocaust memorials remain suspicious to many, since tourism is identified with mass culture, and the bias in the academy against mass culture has deep roots.47 The premise of this volume is not that mass culture is problem free; rather, it is that Holocaust tourism is a multifarious practice that, like other cultural phenomena, includes its good and bad actors and that its ubiquity demands thoughtful reflection by scholars. In an era of globalization, tourism is becoming an increasingly common way to make sense of a world whose expanse is becoming ever more accessible.

The prevalent skepticism against mass or popular culture has done nothing to halt the production of popular portrayals of the murder of two-thirds of Europe’s Jews. New films, novels, histories, memoirs, and even forged testimonials appear year after year, reaching a diverse global audience and also eliciting a common critical response. Whatever the most recent Holocaust-themed novel or film may be, criticisms of it as voyeuristic or exploitative, as inadequate or inaccurate, are practically assured.48 Among the voices in debates about the inability of mainstream culture to address the Shoah appropriately, none has been more influential than that of the recently deceased Elie Wiesel. A survivor of Auschwitz and a Nobel Prize–winning author, Wiesel has been one of the most powerful voices to situate the Holocaust in Western thought as an event whose horror lies beyond our ability to understand yet commands future generations to remember.49 A refrain in Wiesel’s writing and speaking is that the Holocaust can never be fully comprehended by those who did not experience it, that it must forever remain a mystery to those who were not there. So what is the best way to portray an event that cannot be fully understood? In his own writing, Wiesel reflects on this challenge by insisting that his works do not fit neatly into generic categories. Discussing his own book, A Beggar in Jerusalem, Wiesel contends that it “is neither novel nor anti-novel, neither fiction nor autobiography; neither poem nor prose—it is all this together.”50 Wiesel’s motivation for negating any specific generic claim for his work is a response to the epistemological challenge presented by Auschwitz, suggesting that whatever the genre or medium, each effort to convey the Holocaust will necessarily prove inadequate, at best offering only a partial account.

Wiesel’s skepticism about the adequacy of forms of representation to portray the Holocaust extends to popular culture more generally. In his critique of the 1978 NBC miniseries Holocaust in the New York Times, he makes abundantly clear his mistrust of television as a sufficiently dignified or sophisticated medium for portraying the profundity of the Holocaust:

Untrue, offensive, cheap: as a TV production, the film is an insult to those who perished and to those who survived. In spite of its name, the “docu-drama” is not about what some of us remember as the Holocaust.

Am I too harsh? Too sensitive, perhaps. But then, the film is not sensitive enough. It tries to show what cannot even be imagined. It transforms an ontological event into soap-opera.51

While no portrayal could ever adequately represent an event that “cannot even be imagined,” Wiesel implies there are some media that should be disallowed a priori on the basis of their apparent shallowness. With the television miniseries as emblematic, Wiesel’s critique sees in contemporary mass culture an inability to deal with philosophical problems in any depth. Instead, he concludes, the mass cultural medium of television turns history into entertainment.52 (Wiesel was to take this skepticism into his work for the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, where he was insistent on a presentation of the Holocaust that would resist the public’s desire for a redemptive narrative that invited universal identification with the victims.)

The case of the miniseries Holocaust proves illustrative of the danger in discounting mass cultural productions too easily. Panned by Wiesel and others as melodrama (a critique that was certainly justifiable, but hardly exhaustive), the broadcast in fact marked a pivotal moment in the United States and elsewhere in bringing the Holocaust to the forefront of cultural consciousness. Nowhere was this truer than in the Federal Republic of Germany, where the miniseries was the most widely viewed television event on record up to that time and which, as the German film scholar Anton Kaes has written, “broke through thirty years of silence and left an indelible mark on German discussion of the Holocaust.”53 This discussion included both media and politicians and may have affected voting patterns among the members of the Bundestag.54 In an article from 1980 on the broadcast, the German studies scholar Mark Cory suggests that the miniseries had an impact beyond the living room: “Visitor attendance at Dachau is up sixty percent since the broadcast in Germany, … Paraguay has been persuaded to revoke the citizenship of Josef Mengele, and … the Federal Republic of Germany has abolished the statute of limitations on war crimes scheduled to halt new prosecutions of atrocities after December, 1979.”55 The link Cory points out between tourism to Dachau and the television broadcast is especially telling and suggests that the television show may have initiated a deeper search for truth about the Holocaust and that visits to locations depicted in the television show, however inaccurately, figure as one element in that search for a more authentic encounter with history. Perhaps audiences appreciated the limits of the miniseries as a genre while grasping the import of the event it so imperfectly portrayed, thus begetting a deeper search for more authentic portrayals that might be found on site.

In fact, popular culture has supplied numerous examples of works that have had an enormous impact on Holocaust remembrance for many decades. A well-known case, one that long predates NBC’s television broadcast, also points to a definite link between representations in mainstream culture and tourism. Anne Frank’s diary, and the play based on it, had already achieved international renown in the 1950s, and they continue to be featured as a regular part of school curricula in many countries.56 There have been numerous film versions of Anne’s story, shown on television and in cinemas. The broad appeal of Anne Frank’s diary has much to do with the author’s undaunted optimism, which tends to eclipse the gruesome fate that awaited the young woman at Bergen-Belsen in 1945 (she died of starvation and disease under the murderous conditions the Nazis fostered in the camps). Because of the sense of faith in humanity that the diary expresses, some scholars question the centrality of her diary as an appropriate vehicle for Holocaust remembrance, since it fails to confront the death that awaited millions of victims like her. The Holocaust scholar Lawrence L. Langer writes of Anne Frank and her diary’s legacy, “She is in no way to blame for not knowing about what she could not have known about. But readers are much to blame for accepting and promoting the idea that her Diary is a major Holocaust text and has anything of great consequence to tell us about the atrocities that culminated in the murder of European Jewry.”57 Furthermore, Frank edited her diary for eventual publication as a book, so it is both a document of her experience as well as an aestheticized text. In short, its status as a source of information about the Holocaust is problematic, even if one concedes that Frank and her family were hardly the only Jews to hide from their persecutors and that these stories depict an aspect of the Holocaust experience that merits attention. But as a catalyst for engagement with the Holocaust, there have been few works that have made such an indelible mark on their readers.

The link between Anne Frank’s story and Holocaust tourism is striking: Lines of tourists queue up to see the house in Amsterdam where the young girl hid with her family, making it one of the city’s most heavily visited destinations.58 In what ways do visitors to the house encounter similar questions we might ask about the book, the play, and the films? Do visits to the house distort the reality of the Holocaust by focusing, not on violence and death, but on a doomed effort to survive? Does the museum portray the Holocaust accurately or in a morally responsible way? Does it educate, entertain, or do both? Clearly there are as many responses to these questions as there are tourists at the Anne Frank House. There is good reason to be suspicious of the insights gained by some visitors, but surely some of those who see the exhibit are capable of critical reflection on the Holocaust and its memorialization. Furthermore, whether through reading her diary or touring her house, Anne Frank’s story can be a point of entry into learning about the Holocaust that does not end when the last page is turned or the museum’s exit is reached.

Holocaust Tourism: A Phenomenological Approach

As the examples of the miniseries Holocaust and the Anne Frank House show, the collective remembrance of the Holocaust depends at least in part on representations in mainstream culture, and tourism has a close connection to other forms of popular culture in literature, film, and television. Holocaust tourism raises many of the same questions about what can be known about the calamity, and how we can know it, that other genres do, but it also adds other considerations about places of memory. In turn, what we discover about tourism to sites of Holocaust remembrance can inform how we consider reading texts or viewing films. A common feature of many essays on the ethics of Holocaust representation is that the perspectives of readers and viewers are usually secondary to considerations of aesthetic form. Most critics of Holocaust-related cultural productions foreground matters of genre or medium when analyzing a book, a memorial, or a film, exploring their signifying structures and codes as if they were determinative of their meaning independent of the audience with which they engage. Just as texts need readers to generate meaning, tourism is not possible without tourists. Of course, form matters, and this book pays attention to formal aspects of tourism: how museums are arranged, how tour guides shape the experiences of visitors to camp memorials, how displays use text and image, and so on. But the perspective of tourists remains central to the inquiry, which, relying on a term first articulated by the social anthropologist Eric Cohen and further developed by other scholars since, I am characterizing as a phenomenological approach to Holocaust tourism.59 By that I mean that it is an account of the ways in which tourists interpret sensory stimuli to produce knowledge and negotiate their identities in relation to the surrounding place.60 That includes a consideration of how tourists encounter visual displays of artifacts, photos, and documents; how their hearing is addressed both intentionally through audio recordings, lectures, or guides communicating through headphones, as well as through ambient sources, including other tourists; or how tourists’ bodies navigate configurations of space. Tourism, though heavily visual, relies on a full array of sensory experience in imparting both rational and more affective impressions to travelers. In the case of Holocaust tourism, I address how tourists process their encounters with places of remembrance, including their affective and sensory qualities, in order to construct a coherent narrative of the Holocaust and to situate themselves in relation to the event and its memory.

In applying this approach, I place more emphasis on exploring the possibilities for knowledge than on a quantitative or statistically verifiable ethnographic account of Holocaust tourists. Such work would be a welcome contribution to the study of Holocaust tourism, but it must build on an awareness of the full range of available responses that tourists have to Holocaust sites if it is to ask the right questions.61 Furthermore, it will have to confront the reality that tourists to Holocaust sites come from such a variety of backgrounds and experiences that any effort to make definitive claims about the phenomenon will face enormous challenges in identifying broad trends shared among different visitors. This book identifies an observed range of subjectivities available to travelers: not just as consumers, but also as witnesses, pilgrims, mourners, commemorators, students, and educators. By linking the questions about knowledge and representation that drive Holocaust studies with theoretical and empirical insights from tourism studies, this book aims to offer a rich account of those who undertake travel to these destinations and what they recall, including my own experiences and those of other travelers, who often share their responses in print and online media. It also draws on conversations with tour guides, reports by agencies that manage such sites, and tourist literature. It identifies tourist responses to sites that go beyond a description of the business of tourism, although I pay attention to the role of market forces in shaping accessibility to sites of remembrance. In addressing the possibilities for knowledge and acknowledging a range of responses, I hope to counter a prevailing tendency in many common responses to tourism at Holocaust museums and memorials, namely that it is appalling that a market for this kind of travel exists. This tendency, which finds expression in both general and more academic critiques of tourism, has played an especially important role in one particular branch of tourism studies concerned with “dark tourism.”

As noted above, the term “dark tourism” was coined by J. John Lennon and Malcolm Foley, British researchers of tourism and management. Lennon and Foley define “dark tourism” as travel to places of death and disaster, including Auschwitz, Hiroshima, Robben Island, and the Sixth Floor Museum in Dallas, which is dedicated to the assassination of President John F. Kennedy. Such places draw tourists because of the heavy circulation within media accounts of the calamities that took place there. Indeed, for Lennon and Foley it is the mediatized nature of these places (or, rather, of the events they have come to represent) that links them together, lending them an allure within mainstream culture that they might not otherwise possess. (We see here an echo of the concern for mainstream culture that runs from Horkheimer and Adorno through to Wiesel.) These aspects of dark tourism theory certainly reinforce the connection between Holocaust tourism and other forms of popular culture. But for Lennon and Foley the association is rather negative, raising questions of poor taste on the part of travelers whom they regard as “invariably curious about suffering, horror and death,” which become “established commodities” within the tourism industry.62 While Lennon and Foley allow that some tourists may have more noble motivations than others, their typical dark tourist is the traveler seduced by media images into spending money on an inauthentic experience.63 Ultimately, dark tourists appear as postmodern travelers who disregard the distinction between the original event and its subsequent representations.

Like many other critiques of tourism, the dark tourism model focuses on tourism as commodification. Evoking familiar concerns about mass culture, dark tourism sees those who purchase tourism’s commodities as submitting to the dominant logic of capitalism—the logic that Adorno and Horkheimer saw as enabling the establishment of extermination camps. A certain superficiality adheres to the rather obvious and not very insightful observation that tourism involves commodification. It is as if, by establishing a fact that few would legitimately dispute, one has adequately dispensed with an age-old phenomenon that continues to diversify and draw ever more people into its networks.

Despite the admonitions about the dangers of commodifying history as aesthetic object, we cannot ignore the impact of tourism in disseminating awareness of the genocide. Nor did Adorno ever imagine that his negative critique of mainstream culture would obviate all engagement with a calamity that has so often been called “unthinkable.” Too negative a view of mainstream culture bears a defeatist, even elitist element that cannot imagine resistance or critical reflection as a widespread practice within humanity. And to insist on the incomprehensibility of the Holocaust on the basis of its horror is to invite resignation in the face of atrocity.64

Instead, horror can motivate comprehension. Even Adorno advocates for a moment beyond or apart from rational thought, for an affective moment that is productive. Specifically, he insists that we recoil in the face of Auschwitz. When we learn of the gas chambers and the mass executions in forests and the deaths from starvation and disease, we should respond in horror, but that horror, in turn, should lead us to engage in deep thought about the structures and systems in any society that produce violence. However we engage with the Holocaust, there is a place for affect in our pursuit of knowledge. To dismiss tourism as an inauthentic fascination with the macabre is to ignore the ways in which affect becomes the grounds upon which a critical rationality can build.65

Of course, we can maintain a distinction between genuine affect and the kind of sentiment fostered in mass entertainment that Adorno and others would dismiss as kitsch. Holocaust tourism comprises a range of efforts that span the sincere to the sensationalized. And yes, there are “dark tourists” who are drawn to the macabre—but they don’t necessarily leave the destination with the same morbid curiosity that might initially have drawn them. And even some who conceive of their travel as pilgrimage may, in fact, exhibit a superficial engagement with the site they visit. The point is, tourists are capable of varied and even contradictory behaviors and insights during the same journey. Travel to museums, memorials, and other locales related to the murder of six million European Jews can be both problematic and productive. Holocaust memorial sites evoke affective responses through a variety of representational strategies, some more capable of engendering reflection than others. It is time to see in tourism a sincere effort on the part of many travelers and their hosts, if not all, to engage with a topic that is so ubiquitous in Western culture and that challenges many basic beliefs people have about themselves, about the nature of good and evil, and about the value of human life in all its diversity. In tourism, I locate an effort by many travelers to claim agency in relation to Holocaust memory. Holocaust tourists are searching for truth amid a sea of representations about the twentieth century’s most notorious event. The knowledge that tourists seek is embodied in space, and that fact of embodiment is, I argue, central to the experience of Holocaust tourism. By going directly to sites of perpetration, they are looking for a sense of immediacy to history, even though their encounters are ultimately mediated through strategies of memorialization. When visiting museums in places that are remote from the site of perpetration (such as Yad Vashem in Jerusalem or the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, DC), tourists are nonetheless exploring a spatial reality that is very distinct from that which surrounds the exhibition. The fact that tourists can never inhabit the Holocaust itself, only its traces and its representations, opens the door to questions about absence and presence, about the past and the present. The embodied encounter with the traces of mass murder also motivates reflection on the physical and the metaphysical and about the ephemeral materiality of one’s own body, one’s temporality, and the possibility—or impossibility—of finding transcendence or redemption in sites of extreme suffering. These are the stakes that are foregrounded in the subsequent chapters.

Organization of the Book

The organization of this book is both thematic and geographic. Part I, “Tourism at the Camp Memorials,” takes up tourism to concentration camps, paying special attention to those that were specifically designated as extermination centers. The camps have epitomized the Nazi genocide in the public imagination, even though many victims of the Holocaust perished in ghettos from starvation and disease or faced death by mobile killing squads near their own villages.66 Here we consider the experiences of memorial space that tourists encounter during their visits. Part II, “Urban Centers of Holocaust Memory,” moves increasingly outward from the camps as the epicenters of mass murder. It examines how the Holocaust is represented to future generations, looking at four urban centers of Holocaust remembrance. The first two are Warsaw and Berlin, both sites of Holocaust perpetration, although in very different ways. The second two are Jerusalem and Washington, DC, where the Holocaust has been memorialized in museums and archives in two nations that each lay claim to the history of the Holocaust—again, in very different ways. By looking comparatively at four national capitals with different degrees of connection to the Holocaust, we can consider how these sites vary in their strategies for collective memory.

Ultimately, this book engages with a broad range of perspectives—historical and theoretical, documentary and fictional, academic and informal—to produce a more differentiated account of Holocaust tourism. The aim is not to generate a unified theory of tourism and Holocaust remembrance but, rather, to lay a foundation for a more nuanced, less disciplinarily bound approach to both. In attempting such a discussion here, I participate primarily as a humanist, albeit one who is hoping to learn from and contribute to the work of social scientists, historians, and a diverse audience of tourists. I draw on both my own experiences and those of other visitors to Holocaust memorial sites, not with the aim of quantifying particular responses, but to give some sense of the range of responses that Holocaust tourism can elicit. If the balance of the arguments here seems to emphasize the positive features of Holocaust tourism, that is because such arguments are much harder to find elsewhere, and by presenting them here, perhaps I can contribute to a more reflective, less reactive discussion. At the same time, the productive contributions made to Holocaust memorialization through tourism are inextricable from the commercial practices that accompany them and that point to the problematic ethics of travel and spectatorship. The arc of this book’s argument ties the phenomenon of visits to Holocaust-related sites to other discussions about Holocaust understanding and representation. In doing so, it demands a serious look at tourism itself as a mode of representation and interpretation and thereby claims tourism as an object of study not only for anthropologists, sociologists, and economists but also for philosophers, literary critics, and art historians.

By bringing tourism into the realm of Holocaust studies, this book also represents an effort to move beyond some of the more dogmatic, doctrinal aspects of research into the Nazi genocide that have had the unfortunate consequence of preempting certain lines of inquiry, at least until recent years. Those doctrines, which we will explore in greater detail throughout the volume, include such notions as the impossibility of representing the Holocaust; the cautions against comparisons of the Holocaust with other genocides; and the insistence that the Holocaust offers no redemptive potential through aesthetic production, no ultimate meaning that can be salvaged from such senselessness. In many ways I embrace these doctrines and have certainly been stamped by them in my own development as a scholar, but at the same time I believe it is necessary to recognize their limits and, frankly, their shortcomings for generating Holocaust remembrance in an era after the survivors have gone.

Ultimately, Holocaust tourism represents the emergence of an evolving way of grasping human experience that can range from the simplistic to the sophisticated. By examining the phenomenon, perhaps it is not too crass to hope that Holocaust tourism can continue to confront the full range of human capabilities, from the brutal to the noble.